Primary Cutaneous Cryptococcosis: A Rare Masquerading Presentation of Cryptococcus Infection

Tanisha Bharara1, Shalini Upadhyay2, Mohinder Pal Singh Sawhney3, Manisha Khandait4

1 Assistant Professor, Department of Microbiology, SGT University, Gurgaon, Haryana, India.

2 Assistant Professor, Department of Microbiology, SGT University, Gurgaon, Haryana, India.

3 Professor and Head, Department of Dermatology, SGT University, Gurgaon, Haryana, India.

4 Professor and Head, Department of Microbiology, SGT University, Gurgaon, Haryana, India.

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr. Shalini Upadhyay, SGT University, Gurgaon-Badli Road, Chandu, Budhera, Gurgaon, Haryana, India.

E-mail: shalini.upd@gmail.com

The yeast, Cryptococcus is widely present in the environment. Its main portal of entry is the respiratory tract. Clinical and experimental evidences indicate that cryptococcosis is usually a reactivation of a dormant infection. They have been recovered from soil contaminated with avian excreta, especially pigeon droppings and from decaying wood, fruits, vegetables and dust. Cryptococcus may be found on skin of healthy subjects without causing any manifestation but it is known to cause life threatening infection in immunocompromised hosts. Primary Cutaneous Cryptococcosis (PCC) is an uncommon condition which is characterised by localised cryptococcal skin eruptions without dissemination to internal organs. Clinicians are aware of the typical presentation of cryptococcal infections occurring mostly in immunocompromised patients. Rare manifestations like PCC may go unnoticed leading to prolonged morbidity and health care cost. The present article is a case report of PCC in a 39-year-old immunocompetent male who presented with two months history of scattered erythematous indurated papules and plaques on his right foot, arm and abdominal region developed after having suffered minor injury at the cement factory. The patient was started on fluconazole to which he responded well.

Fungal infection, Immunocompetent, Skin eruptions, Yeast

Case Report

A 39-year-old male patient, labourer in cement factory, presented to Dermatology, Outpatient Department with rapidly enlarging plaques on his right foot, forearm, thigh region and lower abdomen. Two months back patient was asymptomatic, when he got a superficial bruise on his right foot at his work place. Subsequently, he developed pruritus and erythema at the site of injury. Initially the erythematous itchy area changed to red rash which eventually changed to black flaky lesion. He consulted a quack nearby, who prescribed him steroids. He took the medication for two months, but his symptoms were not relieved. The lesion had subsequently spread to his left forearm, groin region, thighs and lower abdomen [Table/Fig-1]. An appropriate consent was obtained from the patient.

Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis lesions: a) Ulcerative lesion on patient’s right lower leg; and b) Erythematous papules on patient’s right forearm.

He denied fever, night sweats, malaise or other systemic symptoms. On physical examination, he was found to be afebrile and lymphadenopathy was absent. Laboratory testing showed normal total leucocyte count and haemoglobin. Skin scraping was taken from the site of the lesion and was sent to the Microbiology laboratory for potassium hydroxide (KOH) mount and fungal culture. One part of the sample was inoculated in two tubes of Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) and incubated at 37°C and 25°C, respectively. Other part of the specimen was incubated in a tube containing 10% KOH at 37°C for two hours.

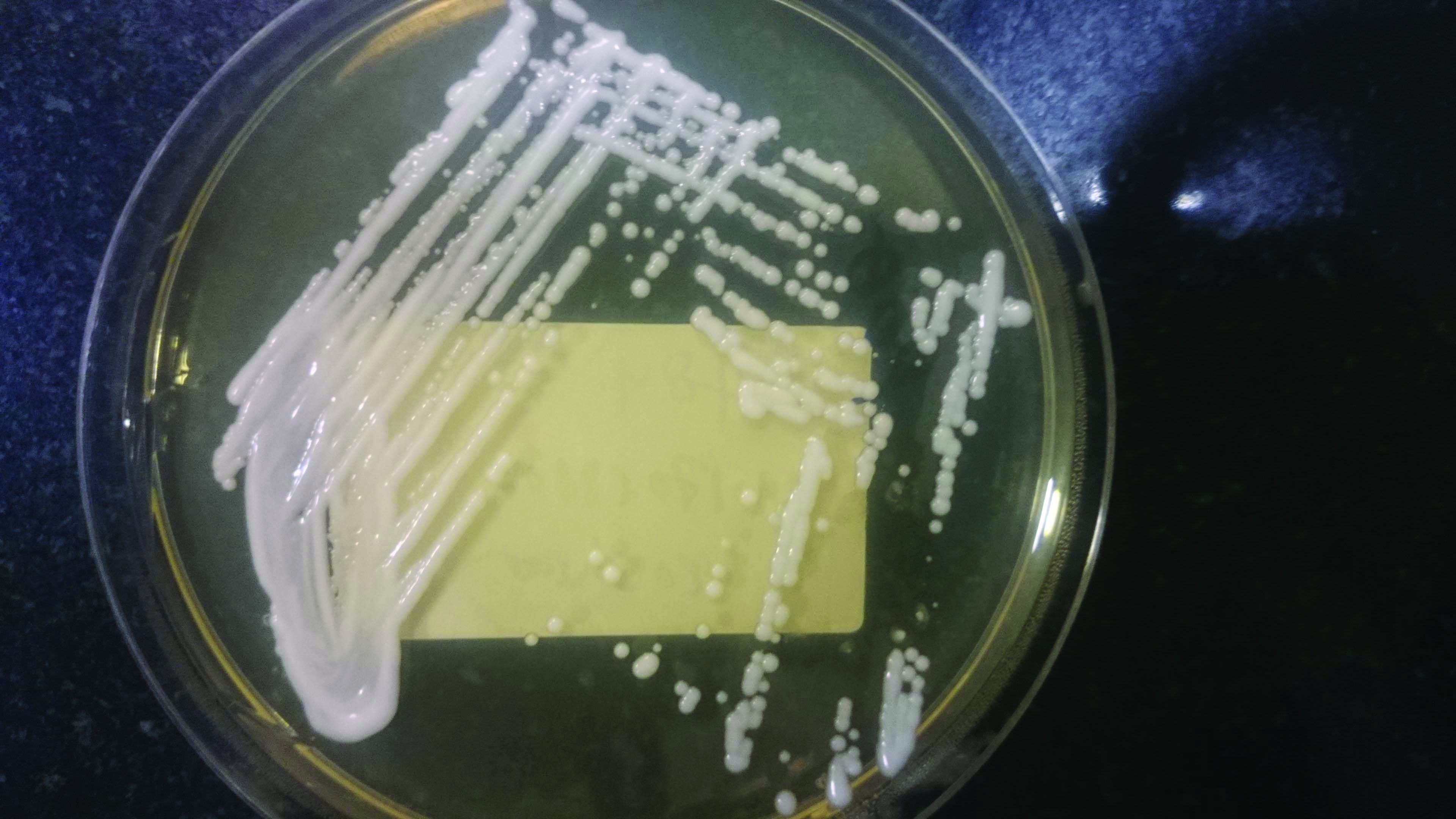

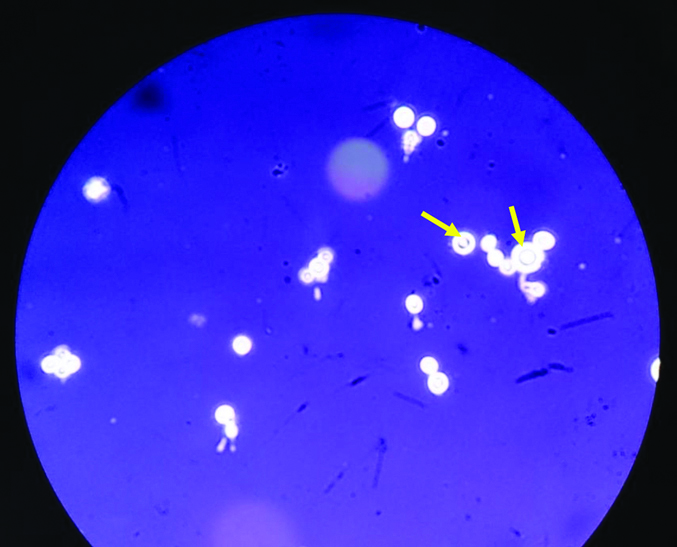

The KOH findings revealed round yeast cells. The culture on SDA, incubated at 37°C grew moist, creamy colonies after 24 hours [Table/Fig-2]. Lactophenol cotton blue staining revealed round, budding yeast cells and nigrosine staining showed capsulated, round, budding yeast cells [Table/Fig-3]. Urease test was subsequently performed and was found to be positive. On the basis of above findings, the organism was identified as Cryptococcus species. The patient was HIV negative and did not give any history of prolonged past illness.

The moist, creamy white colonies of Cryptococcus on Sabouraud’s dextrose agar.

The negative staining of capsule marked with yellow arrows seen around round budding yeast cells at 40x magnification with nigrosine stain.

Upon confirmation of fungal infection, he was started on fluconazole (400 mg daily) based on the culture report. The patient’s lesion improved remarkably over the course of his treatment with near resolution of the surrounding erythema. His steroid was gradually weaned down. Patient responded well to the medication. He was asked to continue the medication for three months and follow-up after one week. At first-week follow-up, his wound showed great improvement. He tolerated fluconazole well and was continued on the same treatment for an additional three months for a total duration of six months. From the start of lesion till his last visit, he never showed sign of relapse or any disseminated disease.

Discussion

Primary Cutaneous Cryptococcosis (PCC) is defined as isolation of Cryptococcus species from a skin lesion without evidence of simultaneous disseminated disease [1]. The cases of PCC reported from all over the world and even occasionally from India, over the last 10 years have been depicted in [Table/Fig-4] [2-26]. A survey conducted by the French Cryptococcosis Study Group (1985-2000) identified 28 cases of PCC from 1,974 Cryptococcosis cases reported to the National Reference Centre for Mycoses. Of these 28 patients, 14 were immunocompetent suggesting that PCC can develop regardless of immune status. PCC usually presents as solitary lesions mostly located on unclothed areas while disseminated disease present as scattered umbilicated papules resembling Molluscum contagiosum [1].

Reports of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis around the world in the last decade [2-26].

| Year of Publication | Authors/Reference | Region | Age (years)/Gender | Immune status | Occupation/Exposure | Site of lesion | Type of lesion | Outcome |

|---|

| 2011 | Leão CA et al., [2] | Brazil | 75/M | Immunocompetent | Eucalyptus logs handler | Forearm | Nodule | Recovery |

| 2011 | Lingegowda BP et al., [3] | Singapore | 37/M | Immunocompetent | Forklift driver | Scalp | Nodule | Recovery |

| 2012 | Kulkarni A et al., [4] | India | 55/M | Immunocompromised | Repeated insulin and heparin subcutaneous injections | Thigh | Umbilicated | Unrelated death |

| 2012 | Marques SA et al., [5] | Brazil | 11 patients, mean age 71.2/9M2F | 5 immunocompetent, 6 on corticosteroid therapy | 5 out of the 11 cases reported trauma or exposure to contaminated sources | Upper limbs | Circumscribed lesions ranged from an infiltrative plaque to a solid tumour mass | 9 cured, 1 unrelated death, 1 marked improvement |

| 2012 | Spiliopoulou A et al., [6] | Greece | 58/M | Immunocompetent | Poultry farmer | Hand | Ulceration | Recovery |

| 2012 | Pasa CR et al., [7] | Brazil | 59/M | Immunocompetent | Firewood collection | Forearm | Ulceration | Recovery |

| 2012 | Narváez-Moreno et al., [8] | Rural Central America | 66/M | Immunocompetent | Not reported | Penis | Nodule | Recovery |

| 2013 | Lu YY et al., [9] | Rural area of Taiwan | 87/M | Immunocompetent | Not reported | Arm | Indurated papules and plaques | Recovery |

| 2013 | Molina-Leyva A et al., [10] | Spain | 8/F | Immunocompetent | None | Forearm | Macule | Recovery |

| 2014 | Nascimento E et al., [11] | Southeast Brazil | 68/M | Immunocompetent | Bus driver | Forearm | Nodule | Recovery |

| 2014 | Leechawengwongs M et al., [12] | Thailand | 48/F | Immunocompetent | Reported trauma | Lower leg | Inflamed wound | Recovery |

| 2014 | Drogari-Apiranthitou M et al., [13] | Greece | 61/M | Immunocompromised | Injury with a plant thorn | Finger | Ulceration | Recovery |

| 2015 | Wang J et al., [14] | USA | 56/M | Immunocompromised | Carpenter | Right forearm | Plaque | Recovery |

| 2015 | Srivastava GN et al., [15] | India | 56/M | Immunocompetent | Reported trauma | Forehead and ala of nose | Ulcerated nodule | Recovery |

| 2016 | Forrestel AK et al., [16] | Philadelphia | 62/F | Immunocompromised | Reported trauma | Forehead | Nodule | Recovery |

| 2016 | Ajam T et al., [17] | USA | 76/F | Immunocompromised | Gardener | Forearm | Papule | Recovery |

| 2016 | Hyde K et al., [18] | Rural Central Texas | 10/F | Immunocompetent | None | Foot | Ulcerated nodule | Recovery |

| 2017 | Landucci G et al., [19] | Italy | 75/M | Immunocompromised | Not reported | Forearm | Papule | Recovery |

| 2017 | Arjona-Aguilera C et al., [20] | Spain | 42/F | Immunocompromised | Probable contact with pigeon | Thigh | Edematous painful plaques | Recovery |

| 2018 | Henderson GP and Dreyer S [21] | California | 69/M | Immunocompromised | Reported trauma | Forearm | Ulceration and bullae | Recovery |

| 2018 | Hobbs M et al., [22] | Rural Mississippi | 6/F | Immunocompetent | Not reported | Right Eyelid | Abscess | Recovery |

| 2019 | Beatson M et al., [23] | USA | 80/M | Immunocompetent | Pigeon breeder | Cheek, ear | Papules | Recovery |

| 2020 | Shalom G and Horev A [24] | Israel | 30/F | Immunocompromised | Owned birds and pigeons | Erythropoietin derivative injection sites | Ulcer | Recovery |

| 2021 | Gaviria Morales E et al., [25] | Switzerland | 60/F | Immunocompetent | Injury caused by a rose thorn | Right thumb | Erythematous ulcerated nodule | Recovery |

| 2020 | Patil SM et al., [26] | USA | 63/M | Immunocompromised | None | Occipital scalp | Plaque lesion | Recovery |

| 2021 | Present case | India | 39/M | Immunocompetent | Trauma | Lower leg and forearm | Papule and ulcer | Recovery |

The most common sites of PCC infection are the extremities, probably because they are mostly exposed and prone to minor injuries. In most of the patients, certain areas having underlying skin disease or site of injury provide a portal of entry for PCC [14]. There was history of bruise at the cement factory preceding the lesion in the presented case. The patient had affirmed the presence of pigeons at his work place. So, it can be hypothesised that the patient may have got the infection through exposure to either infested soil or bird droppings. The cutaneous manifestations of cryptococcosis may mimic other dermatological conditions, such as, fungal infections (Sporothrix schenckii, Coccidioides immitis, Blastomyces dermatitidis and Histoplasma capsulatum), varicella lesions, lepromatous leprosy and insect bite. Based on the cases reviewed as well as the findings in the present case a checklist has been prepared to aid in diagnosis of PCC [Table/Fig-5] [1,5,11,14].

Checklist for identification of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis [1,5,11,14].

| Criteria | Evidence of PCC |

|---|

| Skin lesion | Confined to limited body area |

| Site of origin | Unclothed area (limbs) |

| Injury | History of prior injury or former skin lesion Identical body site for prior injury or former skin lesion Hobby or occupation predisposing to skin injury

|

| Exposure | Possible contaminated source |

| Living area | Rural |

| Underlying disease predisposing to cryptococcosis | None |

| Extracutaneous sites positive for Cryptococcus | None |

| Outcome of infection | Favourable |

The majority of patients diagnosed with PCC underwent laboratory investigations to evaluate host immune status and to rule out disease dissemination. Many patients had serum and Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) cryptococcal antigen studies and/or cultures (sputum, blood, urine or CSF) performed and all cultures and CSF antigen were reported as negative [9,11,18,24,25]. In a few immunocompetent patients no culture or latex agglutination data were obtained, and had no radiographic evaluation for pulmonary cryptococcosis [7,11]. Although, the present case was HIV negative and he did not any history of prolonged illness in the past; one of the limitations of this study was that extensive work up to rule out disseminated disease could not be performed on the patient neither serotyping of the isolated strain was done due to resource constraints.

The treatment for cryptococcosis is determined by the type of infection and the immune status of the host. The Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) recommends oral azole therapy for 6-12 months for patients with non-central nervous system, non-disseminated Cryptococcus [26]. The present case had a favourable response to fluconazole monotherapy and topical wound care after only a few weeks of treatment. A single documented treatment failure reported in literature, in an immunocompromised patient, was discovered at autopsy after three months of antifungal therapy [27].

Conclusion(s)

This case was an aide memoire about the risk factors, clinical presentation and prompt response to therapy in a case of PCC. It illustrated the importance of prompt microbiological investigations and thorough evaluation for atypical infections such as PCC.

Author Declaration:

Financial or Other Competing Interests: None

Was informed consent obtained from the subjects involved in the study? Yes

For any images presented appropriate consent has been obtained from the subjects. Yes

Plagiarism Checking Methods: [Jain H et al.]

Plagiarism X-checker: Feb 06, 2021

Manual Googling: Mar 03, 2021

iThenticate Software: Mar 31, 2021 (19%)

[1]. Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, Dupont B, Ronin O, Lortholary O, Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: A distinct clinical entityClin Infect Dis 2003 36(3):337-47.10.1086/34595612539076 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2]. Leão CA, Ferreira-Paim K, Andrade-Silva L, Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus gattii in an immunocompetent hostMed Mycol 2011 49(4):352-55.10.3109/13693786.2010.53069721028946 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[3]. Lingegowda BP, Koh TH, Ong HS, Tan TT, Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis due to Cryptococcus gattii in SingaporeSingapore Med J 2011 52(7):e160-62. [Google Scholar]

[4]. Kulkarni A, Sinha M, Anandh U, Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis due to Cryptococcous laurentii in a renal transplant recipientSaudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 2012 23:102-05. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Marques SA, Bastazini Jr I, Martins ALGP, Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in Brazil: Report of 11 cases in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patientsInt J Dermatol 2012 51(7):780-84.10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05298.x22715820 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[6]. Spiliopoulou A, Anastassiou ED, Christofidou M, Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in immunocompetent hostsMycoses 2012 55(2):e45-47.10.1111/j.1439-0507.2011.02155.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[7]. Pasa CR, Chang MR, Hans-Filho G, Post-trauma primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent host by Cryptococcus gattii VGIIMycoses 2012 55(2):01-03.10.1111/j.1439-0507.2011.02058.x21736630 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[8]. Narváez-Moreno B, Bernabeu-Wittel J, Zulueta-Dorado T, Conejo-Mir J, Lissen E, Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis of the penisSexually Transmitted Diseases 2012 39(10):792-93.10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31825f7e2823007707 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9]. Lu YY, Wu CS, Hong CH, Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent man: A case reportDermatologica Sinica 2013 31(2):90-93.10.1016/j.dsi.2012.07.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[10]. Molina-Leyva A, Ruiz-Carrascosa JC, Leyva-Garcia A, Husein-Elahmed H, Cutaneous Cryptococcus laurentii infection in an immunocompetent childInt J Infectious Dis 2013 17(12):e1232-33.10.1016/j.ijid.2013.04.01723791224 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[11]. Nascimento E, da Silva MEMB, Martinez R, Kress MRVZ, Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent patient due to Cryptococcus gattii molecular type VGI in Brazil: A case report and review of literatureMycoses 2014 57(7):442-47.10.1111/myc.1217624612099 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[12]. Leechawengwongs M, Milindankura S, Sathirapongsasuti K, Tangkoskul T, Punyagupta S, Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus gattii VGII in a tsunami survivor from ThailandMed Mycol Case Rep 2014 11(6):31-33.10.1016/j.mmcr.2014.08.00525379396 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[13]. Drogari-Apiranthitou M, Panayiotides IG, Mastoris I, Theodoropoulos K, Gouloumi A-R, Hagen F, Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis and a surprise finding in a chronically immunosuppressed patientJMM Case Reports 2014 1(3)10.1099/jmmcr.0.003426 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[14]. Wang J, Bartelt L, Yu D, Joshi A, Weinbaum B, Pierson T, Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis treated with debridement and fluconazole monotherapy in an immunosuppressed patient: A case report and review of the literatureCase Rep Infect Dis 2015 2015:13135610.1155/2015/13135625722900 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[15]. Srivastava GN, Tilak R, Yadav J, Bansal M, Cutaneous Cryptococcus: Marker for disseminated infectionBMJ Case Rep 2015 2015:bcr201521089810.1136/bcr-2015-21089826199299 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[16]. Forrestel AK, Modi BG, Longworth S, Wilck MB, Micheletti RG, Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in a patient with multiple sclerosis treated with fingolimodJAMA Neurol 2016 73(3):355-56.10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.425926751160 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[17]. Ajam T, Hyun G, Blue BJ, Rajeh N, Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A case reportAnn Hematol Oncol 2016 3(3):1082 [Google Scholar]

[18]. Hyde K, Warren D, Gavino AC, Primary cutaneous cryptococcal infection with subsequent erythema nodosum in a 10-year-old immunocompetent girlJAAD Case Rep 2016 2(6):494-96.10.1016/j.jdcr.2016.09.00127981228 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[19]. Landucci G, Farinelli P, Zavattaro E, Giorgione R, Gironi LC, Veronese F, Complete remission of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in an immunosuppressed patient after fluconazole treatmentJ Infect Dis Ther 2017 5(4):326 [Google Scholar]

[20]. Arjona-Aguilera C, Jiménez-Gallo D, Collantes-Rodríguez C, Linares-Barrios M, Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: A new case of this rare entityOpen Forum Infect Dis 2017 4(1):ofw27610.1093/ofid/ofw27628480268 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[21]. Henderson GP, Dreyer S, Ulcerative cellulitis of the arm: A case of primary cutaneous cryptococcosisDermatol Online J 2018 24(2):1303010.5070/D324203817029630156 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[22]. Hobbs M, King J, Feghaly RE, Brodell R, Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent 6-year-old femaleSkin 2018 2(4):240-42.10.25251/skin.2.4.6 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[23]. Beatson M, Harwood M, Reese V, Robinson-Bostom L, Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in an elderly pigeon breederJAAD Case Rep 2019 5(5):433-35.10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.03.00631192987 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[24]. Shalom G, Horev A, Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: An unusual injection site infectionCase Rep Dermatol 2020 12:138-43.10.1159/00050878332999649 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[25]. Gaviria Morales E, Guidi M, Peterka T, Rabufetti A, Blum R, Mainetti C, Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis due to Cryptococcus neoformans in an immunocompetent host treated with itraconazole and drainage: Case report and review of the literatureCase Rep Dermatol 2021 13(1):89-97.10.1159/00051228933708089 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[26]. Patil SM, Beck PP, Arora N, Acevedo BA, Dandachi D, Primary cutaneous cryptococcal infection due to fingolimod- Induced lymphopenia with literature reviewID Cases 2020 21:e0081010.1016/j.idcr.2020.e0081032518753 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[27]. Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, Goldman DL, Graybill JR, Hamill RJ, Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of AmericaClin Infect Dis 2010 50(3):291-322.10.1086/64985820047480 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]