Unpredictable Outcome of Large Traumatic Oesophageal Injury: An Experience and Challenges

Mahaveer Singh Rodha1, Satya Prakash Meena2, Subhash Chandra Soni3, Pawan Kumar Garg4, Althea Vency Cardoz5

1 Additional Professor, Department of General Surgery (Trauma and Emergency), All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India.

2 Assistant Professor, Department of General Surgery, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India.

3 Assistant Professor, Department of Surgical Gastroenterology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India.

4 Associate Professor, Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India.

5 Junior Resident, Department of General Surgery, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India.

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr. Satya Prakash Meena, Assistant Professor, Department of General Surgery, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Basani-2, Industrial Area, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India.

E-mail: drsatyaprakash04@gmail.com

Oesophageal injury following blunt or penetrating injury due to road traffic accidents is a rare cause of morbidity and mortality. The outcome of delayed diagnosis of oesophageal injury is mostly life threatening conditions. A 23-year-old female presented with respiratory distress, fever, chest pain and facial deformity, following road traffic accident 15 days back. After evaluation, the patient was diagnosed with septicaemia due to large thoracic oesophageal perforation with left pyothorax. The patient was managed by Video Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery (VATS) decortication with feeding jejunostomy followed by diversion cervical oesophagostomy. The patient was planned for oesophageal reconstructive surgery electively in follow-up period. After six weeks in the follow-up period, surprisingly large thoracic oesophagus perforation and cervical oesophagostomy was healed spontaneously which was confirmed by gastrograffin study. Spontaneous closure of large thoracic oesophageal perforation is the rare outcome of this injury.

Oesophageal perforation, Oesophagostomy, Thoracic, Trauma, Video assisted thoracoscopic surgery decortication

Case Report

A 23-year-old female presented to the emergency with complaints of respiratory distress, fever, chest pain, dysphagia and facial deformity. She had a history of road traffic accident 15 days back. She was admitted to a local hospital and the diagnosis was made as bilateral multiple ribs fractures, left hemothorax with mild shock; which was managed by left side intercostal drainage tube.

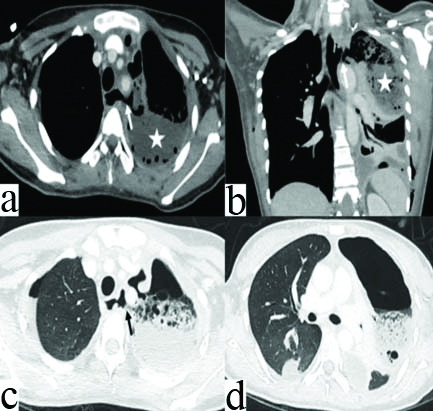

On examination, she had tachycardia, tachypnea, fever, Glasgow Coma Scale 15/15, deformity of face with left side chest crepitations and decreased air entry. Her abdomen was soft non-tender and no external soft tissue injury was present anywhere over the body. Contrast Enhanced Computed Tomography (CECT) chest revealed a rent measuring 15×10 mm size in the left lateral wall of the upper thoracic oesophagus at the level of T2-T3 vertebra and communicating with left sided pleural cavity, bilateral multiple ribs fractures, gross hydro-pneumothorax in the left side [Table/Fig-1]. CECT face suggested body of left half of mandible fracture.

Contrast Enhanced Computed Tomography (CECT) of thorax in axial (a) and coronal (b) plane showing a defect in left lateral wall of oesophagus (white arrow) with a fistulous communication to the left pleural space causing hydro-pneumothorax (asterix). High resolution computed tomography in axial (c) and coronal (d) plane also showing same fistulous communication (black arrow) with presence of left side hydro-pneumothorax causing passive lung collapse.

The total leucocyte count was 20,000/mm3 and other blood investigations were normal. The upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed 15×10 mm sized perforation in the left lateral wall of the upper thoracic oesophagus. Oesophageal stenting was not considered feasible due to friability of tissue.

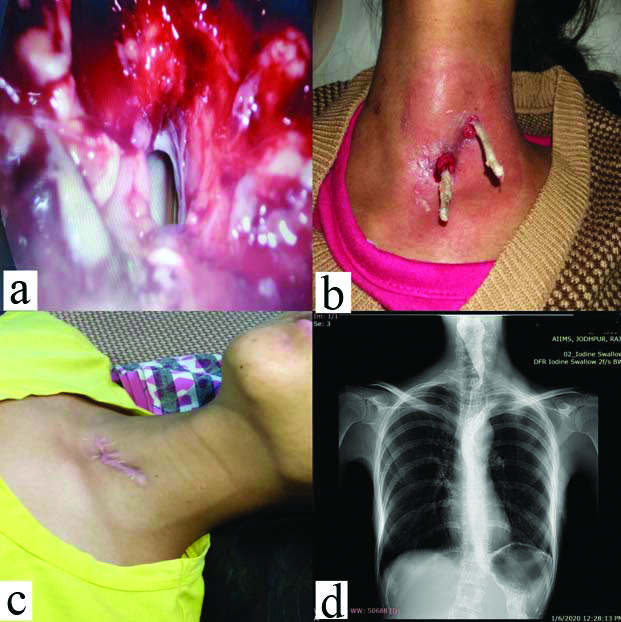

She underwent left-sided VATS decortication after 48 hours of stabilisation. The intraoperative finding suggested collapsed left-sided lung, thick pus flakes and food matter in the pleural cavity. The oesophageal rent was identified with Ryle’s tube and mucous discharge was noted [Table/Fig-2a]. A chest tube was inserted in pleural cavity and feeding jejunostomy was done, followed by diversion cervical oesophagostomy 10 cm proximal to thoracic oesophageal perforation.

(a) Intraoperative image showing oesophageal rent with Ryle’s tube in situ (b) Image showing complete closure of diversion cervical oesophagostomy opening and circumferential tube, inserted outside lumen to prevent retraction of stoma. (c) Follow-up image of diversion oesophagostomy scar over neck (d) Oesophageal gastrograffin study showing no contrast leakage in neck as well as thoracic cavity.

The patient had unstable vitals after seventh postoperative day-pulse 124/minute, blood pressure 88/60 mmHg, temperature 102 F, respiratory rate 30/minute and 200-250 mL pus drainage was found in the left Intercostal Drainage (ICD) tube. X-ray chest showed collapsed left lung with haziness.

Therefore, she underwent VATS decortication and pleural cavity irrigation followed by chest tube drainage. The chest tube was removed on postoperative day 10 after expansion of lungs. She was discharged in stable condition with diversion cervical oesophagostomy and feeding jejunostomy in situ. She was planned for oesophageal reconstructive surgery.

After follow-up period of six weeks, she had spontaneous closure of cervical oesophagostomy [Table/Fig-2b,c] with no signs of a respiratory distress or septicaemia. The gastrograffin study showed no narrowing of the oesophagus or contrast leakage in the thoracic cavity [Table/Fig-2d] and X-ray chest was grossly normal. The patient was allowed for oral diet over one week and she tolerated well with no complications. Patient had no complication after follow-up period of six months.

Discussion

Oesophageal injury following blunt or penetrating injury due to road traffic accidents is a rare cause of morbidity and mortality [1]. The outcome of delayed diagnosis of oesophageal injury is mostly life threatening conditions, especially in thoracic oesophageal perforation. The mortality rate is more than 50% in delayed diagnosis and less than 25% if diagnosis made within 48 hours of injury [2]. This oesophageal injury may be missed in the early presentation, hence good quality of CECT, gastrograffin study and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy are helpful for definitive diagnosis [3].

The outcome of patient depends on size of perforation, location, time of presentation, co-morbidities, associated injuries and aetiology. The most common sites of perforation is cervical followed by thoracic oesophagus. The life threatening complication in cervical oesophageal perforation is less common due to localised contamination in complicated anatomy of neck. In thoracic or abdominal oesophageal perforation, the propagation of contaminated secretion is faster in the pleuro-mediastinal and peritoneal cavity, hence there is poor prognosis [3]. In this case, the patient had complications due to the rapid spread of contents or secretions of gastro-oesophageal mucosa in the mediastinum and thoracic cavity leading to the collapsed lung and plastered pleural cavity with thick pus flakes.

Early intervention of oesophageal perforation has a 10-25% mortality rate [3-5]. In this case, oesophageal perforation was missed initially and detected after 15 days of the injury. In delayed presentation, suturing of oesophageal tear is not preferred, as suture may not hold in the friable surrounding tissue and more chance of bleeding due to disturbed anatomy at the perforation site.

In a few reports, surgical treatment was done according to the size of thoracic oesophageal perforation. Some patients underwent primary repair for small size perforation and others underwent thoracotomy followed by oesophagostomy with cervical oesophagostomy or oesophageal ligation with oesophagostomy for large perforation [3-6]. All patients underwent exploratory laparotomy with feeding jejunostomy for enteral nutrition. Some reports showed successful conservative management of small traumatic perforation of the oesophagus with localised infection in mediastinum only [6,7]. In this case, left pyothorax was the reason for operative intervention and the primary repair was not possible due to delayed presentation. VATS decortication and cervical oesophagostomy were performed instead of primary surgery like thoracotomy, oesophagectomy and oesophageal ligation. The patient had spontaneous closure of oesophageal perforation, which deferred the requirement of major definitive reconstructive oesophageal surgery [7]. She had less chance of morbidity and mortality by performing VATS and loop oesophagostomy.

The authors shared their experience for management of a large thoracic oesophageal injury using a less morbid procedure. There is no constant definitive procedure or type of surgery in this type of case to reduce morbidity and mortality. Minimal invasive surgery may be helpful in delayed presentation of large oesophageal perforation.

Conclusion(s)

Delayed presentation of large thoracic oesophageal perforation is difficult to manage. Minimal access surgery like VATS with pleural drainage and loop oesophagostomy may reduce the chances of morbidity and mortality in the patients. Spontaneous closure of large thoracic oesophageal perforation is the rare outcome of this injury.

Author Declaration:

Financial or Other Competing Interests: None

Was informed consent obtained from the subjects involved in the study? Yes

For any images presented appropriate consent has been obtained from the subjects. Yes

Plagiarism Checking Methods: [Jain H et al.]

Plagiarism X-checker: Oct 01, 2020

Manual Googling: Jan 15, 2021

iThenticate Software: Jan 23, 2021 (3%)

[1]. Makhani m, Midani D, Goldberg A, Friedenberg F, Pathogenesis and outcome of traumatic injuries of oesophagusDis Oesophagus 2014 27:630-36.10.1111/dote.1213224033532 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2]. Sancheti M, Fernandez F, Surgical management of oesophageal perforationOperat Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016 20(3):234-50.10.1053/j.optechstcvs.2016.02.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[3]. Vázquez-Rodríguez JC, Pelet Del Toro NM, García-Rodríguez O, Ramos-Meléndez E, López-Maldonado J, Rodríguez F, Traumatic oesophageal perforation in puerto rico trauma hospital-A case seriesAnn Med Surg (Lond) 2019 44:62-67.10.1016/j.amsu.2019.06.01131316769 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[4]. Andre-Alegre R, Surgical treatment of traumatic oesophageal perforation: Analysis of 10 casesClinics 2005 60:375-80.10.1590/S1807-5932200500050000516254673 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[5]. Søreide JA, Viste A, Oesophageal perforation: Diagnostic workup and clinical decision making in first 25 hoursScand. J Trauma Resusitation Emerg Med 2011 19:6610.1186/1757-7241-19-6622035338 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[6]. Mahmodlou R, Abdirad I, Ghasemi-rad M, Aggressive surgical treatment in late diagnosed oesophageal perforation: A report of 11 casesISRN Surg 2011 2011:86835610.5402/2011/86835622084783 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[7]. Mzoughi Z, Djebbi A, Bayar R, Hamdi I, Gharbi L, Khalfallah T, Traumatic isolated perforation of lower oesophagusTrauma Case Rep 2016 (6):13-15.10.1016/j.tcr.2016.09.00829942853 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]