In the current scenario of COVID-19 pandemic, ‘prevention’ is the key word in wake of non-availability of treatment and wait for an effective vaccine. During this unprecedented time of medical crisis, various preventive strategies have been adopted. Lockdown was valued as one of the important preventive strategies to contain COVID-19 by Government of India [1,2]. Punjab reported its first case on March 8, 2020 [3] and went a step further by imposing statewide curfew for strict implementation of lockdown [4].

The efforts of medical community are focused towards prevention of COVID-19 infection by adopting measures of protecting human host from disease agent. During lockdown, the masses were exposed to intense information regarding prevention from COVID-19 infection. The general population was repeatedly made aware of symptoms, routes of transmission and preventive measures like using masks, frequent hand washing and physical distancing [5]. Various methods including routine mass media like television, radio and newspaper and some innovative aids like giving message through caller tunes of telephones [6] and billboards was utilised for dissemination of information to public with an objective to change individual and community behavior towards prevention of disease in larger populations.

Knowledge, Attitude and Practices (KAP) surveys during Ebola outbreak provided vital information regarding health education [7] and also about the need to prevent stigma related to infectious diseases [8]. Therefore, similar strategy can be utilised in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, in the absence of effective cure, implementation of robust preventive strategy becomes essential to contain the pandemic. KAP surveys on COVID-19 in India have observed good knowledge and right practices towards COVID-19 pandemic among respondents and also identified a gap in perception towards COVID-19 myths and facts [9,10]. However, most of these were online surveys targeting that particular strata of population. Therefore, this study was planned with an objective of assessing knowledge, perceptions and practices of patients about COVID-19 visiting OPD of a health training centre during lockdown period in a rural area of Ludhiana, Punjab. The observations of this study may help public health authorities in timely containment of COVID-19 outbreak in India.

Materials and Methods

A health centre based cross-sectional study was carried out from 1st May 2020 to 15th May 2020 for 15 days in RHTC of Department of Community Medicine, Dayanand Medical College and Hospital, Ludhiana, Punjab, India. Ethics approval for the study was duly obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee. Dayanand Medical College and Hospital Ludhiana (DMCH/R&D/2020-67).

All patients (18 years and above) visiting healthcare facility at RHTC, Pohir during their first-hospital visit from 1st May 2020 to 15th May 2020 were eligible to participate in the study. This was the period when lockdown was in operation across Punjab, but health centres were allowed to function to provide the healthcare services. Therefore, the opportunity was utilised to assess knowledge, perceptions and practices of subjects visiting health centre about COVID-19.

Inclusion criteria: As patient attendance was thin, all patients (18 years and above) willing to participate were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria: Patients who visited the health centre for the second time or more for follow-up, not in a condition to participate due to poor health and not willing to participate were excluded from the study. A total of 486 eligible patients visited during this period. However, one patient did not complete the questionnaire and hence, was excluded from the study. Thus, a total of 485 subjects were finally included.

Data was collected on a pre-tested pre-designed interviewer administered questionnaire after obtaining informed consent in local language. Questionnaire was finalised after seeking opinion of expert faculty members. Health workers (providing regular home-based health promotion and preventive care service to the communities in this rural field practice area for over two decades) who were trained and familiar with the terminology used in the questionnaire, well-versed in local language interviewed the participants in Punjabi under supervision. The first part of the questionnaire had information about socio-demographic characteristics such as age, gender, educational, occupational and marital status of the subjects followed by questionnaire on knowledge (15 questions), perception (2 questions) and practices (3 questions). Questionnaire was adapted from WHO resource [11] and a study conducted in China [12]. Knowledge section had 15 questions about symptoms (questions 1-2), prognosis (question no 3), modes of transmission (questions 4-8) and prevention and control (questions 9-15). All questions had correct/incorrect/not sure options. A correct answer to the question by the participant was given one mark, while all incorrect or not sure responses were assigned zero mark. The total knowledge score ranged from 0-15. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for knowledge part of the questionnaire was 0.670.

For assessment of perceptions, participants were asked to respond to two questions whether they agree/disagree/not sure to presence of stigma against specific people (COVID-19 infected persons, their contacts and those returned from COVID affected areas) and yes/no/not sure to whether feeling low due to COVID-19/restrictions. Practices were measured using three questions and yes/no response by participants to handwashing with soap/water or sanitiser, wearing of facemasks and whether followed physical distancing after leaving home.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 20.0 (IBM SPSS statistics 20.0.0, 2011). Descriptive statistics were presented in frequencies, percentages and mean±Standard Deviation (SD). Student’s t-test (independent samples), one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Pearson’s chi-square test wherever applicable was used to determine the difference between the groups for different variables. All tests were two-tailed and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multiple linear regression analysis using stepwise method was performed to identify socio-demographic factors independently associated with the knowledge score. All socio-demographic variables significantly associated with knowledge score (p<0.05) in the univariate analysis were included in multiple linear regression model with knowledge score as the outcome variable. Unstandardised regression coefficients (β), along with 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) were used to quantify the adjusted associations between exploratory and outcome variables.

Results

The baseline socio-demographic characteristics showed that out of 485 participants, maximum number of the participants 181 (37.3%) belonged to age group of 40-60 years followed by 60 years and above 157 (32.3%). Mean age of the participants was 48.8±16.2 years with a range of 18-88 years. Male participants 248 (51.1%) were marginally higher than females 237 (48.9%). Half of the subjects were educated till 10th grade, while 115 (23.7%) of the subjects had no formal education. A total of 192 (39.6%) participants were homemakers, 51 (10.5%) were shopkeepers or engaged in small business and 47 (9.7%) were farmers. Majority of the participants were married 381 (78.6%) [Table/Fig-1].

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants (N=485).

| Characteristics | Frequency (%) |

|---|

| Age (years) |

| <20 | 11 (2.3) |

| 20-29 | 59 (12.2) |

| 30-39 | 77 (15.9) |

| 40-49 | 88 (18.1) |

| 50-59 | 93 (19.2) |

| 60-69 | 104 (21.4) |

| ≥70 | 53 (10.9) |

| Gender |

| Male | 248 (51.1) |

| Female | 237 (48.9) |

| Educational status |

| No formal education | 115 (23.7) |

| Primary (1st-5th grade) | 140 (28.9) |

| Matric (6th-10th grade) | 126 (26.0) |

| Senior secondary (11th-12th) | 62 (12.8) |

| Graduate and above | 42 (8.7) |

| Occupational status |

| Home maker | 192 (39.6) |

| Service | 66 (13.6) |

| Business | 51 (10.5) |

| Farmer | 47 (9.7) |

| Skilled/Unskilled Worker | 52 (10.7) |

| Student | 12 (2.5) |

| Unemployed | 65 (13.4) |

| Marital status |

| Married | 381 (78.6) |

| Never married | 56 (11.5) |

| Widow/widower | 46 (9.5) |

| Divorced | 02 (0.4) |

A total of 15 questions were used to assess knowledge of the participants about COVID-19. Mean knowledge score was 10.6±2.1 with a range between 3-15. The overall correct score rate came out to be 70.7% (10.6 out of 15) and 357 (73.6%) of them scored 10 or higher marks. Majority of the participants knew about the main clinical symptoms 425 (87.6%), while only 284 (58.6 %) and 276 (56.9%) knew that COVID-19 transmits through respiratory droplets of infected patients and by touching contaminated surfaces. Participants mostly knew about regular handwashing with soap/water or sanitiser (77.7%), isolation and treatment of infected individuals (92.4%), isolation of contacts (95.9%) and wearing face masks (97.3%) as the effective ways to prevention and control. However, only half of them answered correctly that one should avoid crowded places [Table/Fig-2].

Knowledge of participants about COVID-19 (N=485).

| Knowledge assessment | Frequency (%) |

|---|

| Correct | Incorrect | Not sure |

|---|

| The main symptoms of COVID-19 are fever, cough, fatigue and muscle pain | 425 (87.6) | 60 (12.4) | - |

| Shortness of breath is another important clinical symptom | 194 (40.0) | 253 (52.2) | 38 (7.8) |

| Presently, there is no effective cure for COVID-19 | 216 (44.5) | 153 (31.5) | 116 (23.9) |

| The COVID-19 virus spreads through respiratory droplets of infected individuals. | 284 (58.6) | 192 (39.6) | 09 (1.8) |

| The COVID-19 virus spreads through direct contact with infected individuals. | 236 (48.7) | 203 (41.8) | 46 (9.5) |

| Touching contaminated objects/surfaces would result in the infection by the COVID-19 virus. | 276 (56.9) | 203 (41.9) | 06 (1.2) |

| Eating or contacting with infected animals would result in COVID-19 infection | 480 (99.0) | 04 (0.8) | 01 (0.2) |

| The COVID-19 virus infection spreads through airborne | 479 (98.8) | 06 (1.2) | - |

| Regularly washing hands with hand rub or soap and water is one of the methods of preventing COVID-19 | 377 (77.7) | 108 (22.3) | - |

| One can prevent COVID-19 by not touching the eye/nose and regular covering the nose when coughing/sneezing | 321 (66.2) | 153 (31.5) | 11 (2.3) |

| To prevent the infection by COVID-19, individuals should avoid visiting crowded places | 264 (54.4) | 212 (43.7) | 09 (1.8) |

| By avoiding close contact with anyone who has a fever and cough is another method to prevent COVID-19 | 216 (44.5) | 227 (46.8) | 42 (8.7) |

| One should wear face masks to prevent the infection by the COVID-19 virus. | 472 (97.3) | 02 (0.4) | 11 (2.3) |

| Isolation and treatment of COVID-19 infected people are effective ways to reduce the spread to others | 448 (92.4) | 34 (7.0) | 03 (0.6) |

| People having contact with someone infected with the COVID-19 virus should be immediately isolated. | 465 (95.9) | 17 (3.5) | 03 (0.6) |

[Table/Fig-3] revealed that knowledge score differed significantly as per age, educational, occupational and marital status of the participants. Knowledge score increased significantly with the decrease in age (p<0.001) and increase in educational status of the participants (p<0.001).

Socio-demographic characteristics and knowledge score of the participants.

| Characteristics | No. of participants (%) | Knowledge score (SD) | F†/t value†† | p-value |

|---|

| Age (years) |

| <20 | 11 (2.3) | 11.7 (1.8) | 5.558 (F)† | <0.001* |

| 20-39 | 136 (28.0) | 11.1 (1.9) |

| 40-59 | 181 (37.3) | 10.7 (2.1) |

| ≥60 | 157 (32.4) | 10.1 (2.5) |

| Gender |

| Male | 248 (51.1) | 10.7 (2.3) | 0.082 (t)†† | 0.935 |

| Female | 237 (48.9) | 10.6 (2.2) |

| Educational status |

| No formal education | 115 (23.7) | 9.5 (2.5) | 15.259 (F)† | <0.001** |

| Primary (1-5 grade) | 140 (28.9) | 10.6 (2.0) |

| Matric (6-10 grade) | 126 (26.0) | 11.1 (1.7) |

| Senior secondary (11-12) | 62 (12.8) | 11.1 (2.3) |

| Graduate and above | 42 (8.7) | 11.9 (1.6) |

| Occupational status |

| Home maker | 192 (39.6) | 10.5 (2.2) | 5.015 (F)† | <0.001** |

| Service | 66 (13.6) | 11.4 (1.9) |

| Business | 51 (10.5) | 10.6 (1.9) |

| Farmer | 47 (9.7) | 11.1 (2.3) |

| Skilled/Unskilled Worker | 52 (10.7) | 10.2 (2.0) |

| Student | 12 (2.5) | 12.3 (1.4) |

| Unemployed | 65 (13.4) | 9.8 (2.4) |

| Marital status |

| Married | 381 (78.6) | 10.7 (2.1) | 6.885 (F)† | <0.001* |

| Never married | 56 (11.5) | 11.2 (2.4) |

| Widow/Widower/Divorced | 48 (9.9) | 9.7 (2.4) |

| Total | 485 | 10.6 (2.1) |

SD: Standard deviation; †One-way ANOVA test(F); ††Independent sample t-test (t); p<0.05* statistically significant; p<0.001** statistically highly significant

Multiple regression analysis revealed that knowledge score was primarily predicted by educational status. Those participants with education from primary to graduation and above versus no formal education were significantly associated with higher knowledge score (Primary: β=1.054, p<0.001, Graduates and above: β=2.349, p<0.001). Unemployed had significantly lower knowledge score than homemakers (β=-0.581, p=0.041) [Table/Fig-4].

Multiple linear regression depicting factors independently associated with knowledge score of the participants.

| Variable | Coefficient (95% CI) | Standard error | t | p-value |

|---|

| Constant | 9.611 (9.206, 10.02) | 0.206 | 46.67 | <0.001** |

| Primary vs. No formal education | 1.054 (0.536, 1.572) | 0.264 | 3.996 | <0.001** |

| Matric vs. No formal education | 1.548 (1.014, 2.081) | 0.272 | 5.698 | <0.001** |

| Senior secondary vs. No formal education | 1.521 (0.866, 2.176) | 0.333 | 4.563 | <0.001** |

| Graduate and above vs. No formal education | 2.349 (1.607, 3.091) | 0.377 | 6.223 | <0.001** |

| Unemployed vs. Homemakers | -0.581 (-1.137, -0.024) | 0.283 | 2.051 | 0.041* |

Multiple linear regression test using stepwise method; CI: Confidence interval p<0.05* statistically significant; p<0.001** statistically highly significant

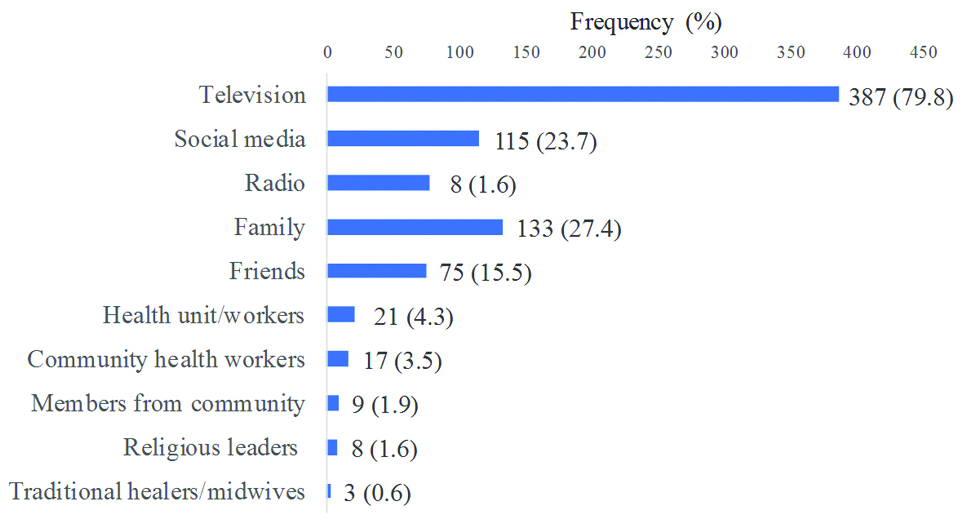

Television was the main source of information (79.8%), followed by social media (23.7%), family (27.4%) and friends (15.5%) about COVID-19 [Table/Fig-5].

Channels of information about COVID-19.

When asked about perceptions, 190 (39.2%) of the participants agreed that COVID-19 generates stigma against specific people, another 98 (20.2%) were not sure and this differed significantly as per their age (p=0.038), education (p<0.001) and occupational (p=0.013) status. Participants who disagreed on stigma had significantly higher knowledge score than their counterparts (p<0.001). Restrictions due to COVID-19 caused low feeling in 283 (58.4%) of the participants, while 34 (7.0%) were unsure about it. Perception of feeling low differed significantly across age groups (p=0.018) and education levels (p=0.033) [Table/Fig-6].

Socio-demographic variables and COVID-19 perceived perceptions of the participants (N=485).

| Variable | COVID-19 generates stigma against specific people | Feeling low due to lockdown or COVID-19 |

|---|

| I. Socio-demographic | Agree (%) | Disagree (%) | Not sure (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | Not sure (%) |

| Age (years)/Total | 190 (39.2) | 197 (40.6) | 98 (20.2) | 283 (58.4) | 168 (34.6) | 34 (7.0) |

| <20 | 3 (27.3) | 7 (63.6) | 1 (9.1) | 8 (72.7) | 3 (27.3) | - |

| 20-39 | 59 (43.4) | 58 (42.6) | 19 (14.0) | 72 (52.9) | 56 (41.2) | 8 (5.9) |

| 40-59 | 77 (42.5) | 70 (38.7) | 34 (18.8) | 121 (66.9) | 52 (28.7) | 8 (4.4) |

| ≥60 | 51 (32.5) | 62 (39.5) | 44 (28.0) | 82 (52.2) | 57 (36.3) | 18 (11.5) |

| p-value (Chi-Square) | 0.038* (13.34) | 0.018* (15.32) |

| Gender |

| Male | 104 (41.9) | 101 (40.7) | 43 (17.3) | 141 (56.9) | 87 (35.1) | 20 (8.1) |

| Female | 86 (36.3) | 96 (40.5) | 55 (23.2) | 142 (59.9) | 81 (34.2) | 14 (5.9) |

| p-value (Chi-Square) | 0.217 (3.05) | 0.598 (1.03) |

| Educational status |

| No formal education | 27 (23.5) | 46 (40.0) | 42 (36.5) | 60 (52.2) | 41 (35.7) | 14 (12.2) |

| Primary | 52 (37.1) | 58 (41.4) | 30 (21.4) | 89 (63.6) | 39 (27.9) | 12 (8.6) |

| Matric | 63 (50.0) | 47 (37.3) | 16 (12.7) | 80 (63.5) | 42 (33.3) | 4 (3.2) |

| Senior secondary | 24 (38.7) | 29 (46.8) | 9 (14.5) | 31 (50.0) | 28 (45.2) | 3 (4.8) |

| Graduate and above | 24 (57.1) | 17 (40.5) | 1 (2.4) | 23 (54.8) | 18 (42.9) | 1 (2.4) |

| p-value (Chi-Square) | <0.001** (41.93) | 0.033* (16.77) |

| Occupational status |

| Home maker | 68 (35.4) | 76 (39.6) | 48 (25.0) | 111 (57.8) | 70 (36.5) | 11 (5.7) |

| Service | 33 (50.0) | 26 (39.4) | 7 (10.6) | 36 (54.5) | 27 (40.9) | 3 (4.5) |

| Business | 19 (37.3) | 23 (45.1) | 9 (17.6) | 28 (54.9) | 20 (39.2) | 3 (5.9) |

| Farmer | 19 (40.4) | 23 (48.9) | 5 (10.6) | 31 (66.0) | 12 (25.5) | 4 (8.5) |

| Skilled/Unskilled Worker | 17 (32.7) | 26 (50.0) | 9 (17.3) | 36 (69.2) | 14 (26.9) | 2 (3.8) |

| Student | 9 (75.0) | 3 (25.0) | - | 8 (66.7) | 4 (33.3) | - |

| Unemployed | 25 (38.5) | 20 (30.8) | 20 (30.8) | 33 (50.8) | 21 (32.3) | 11 (16.9) |

| p-value (Chi-Square) | 0.013* (25.48) | 0.118 (17.91) |

| Marital status |

| Married | 144 (37.8) | 159 (41.7) | 78 (20.5) | 217 (57.0) | 137 (36.0) | 27 (7.1) |

| Never married | 30 (53.6) | 20 (35.7) | 6 (10.7) | 40 (71.4) | 13 (23.2) | 3 (5.4) |

| Widow/Widower/Divorced | 16 (33.3) | 18 (37.5) | 14 (29.2) | 26 (54.2) | 18 (37.5) | 4 (8.3) |

| p-value (Chi-Square) | 0.073 (8.55) | 0.323 (4.67) |

| II. Knowledge Score (SD) | 10.9 (1.8) | 11.3 (1.9) | 8.6 (2.3) | 10.9 (2.1) | 10.6 (2.2) | 8.7 (2.4) |

| p-value (F) | <0.001** (64.692)† | <0.001** (15.121)† |

SD: Standard deviation; †One-way ANOVA test: F; p<0.05* statistically significant; p<0.001** statistically highly significant

As far as practices were concerned, 360 (three-fourth) participants were regularly washing hands with soap/water or sanitiser and had significantly higher knowledge score than those who practiced no handwashing (10.9 vs. 9.7, p<0.001). On further analysis, it was observed that as age advanced, handwashing practices significantly decreased (p=0.008) and increased with increase in education status of the participants (p<0.001). There was a significant difference (p=0.013) according to the marital status of the participants. No significant difference was observed between occupation and handwashing practices (p=0.240). Only 145 (29.9%) participants wore three layered cotton/surgical mask when leaving home and another 331 (68.2%) wore a simple cloth face-cover as a mask. Wearing of masks differed significantly across gender (p=0.045*) and marital status of the subjects (p=0.042). Participants wearing three layered masks had significantly higher knowledge score than their counterparts (p<0.001). Only 161 (33.2%) participants followed physical distancing with males (40.3%) following more than females (25.7%) (p<0.001). However, knowledge score had no significant association with physical distancing (p=0.916) [Table/Fig-7].

Socio-demographic variables and preventive practices followed by the participants (N=485).

| Variable | Washed hands with soap/water or hand rub | Consistently wore face-mask when leaving home | Followed physical distancing |

|---|

| I. Socio-demographic | Yes (%) | No (%) | Cloth face cover (%) | 3 layered cotton/Surgical mask (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) |

| Age (years)/Total | 360 (74.2) | 125 (25.8) | 331 (68.2) | 145 (29.9) | 9 (1.9) | 161 (33.2) | 324 (66.8) |

| <20 | 10 (90.9) | 1 (9.1) | 9 (81.8) | 2 (18.2) | - | 7 (63.6) | 4 (36.4) |

| 20-39 | 113 (83.1) | 23 (16.9) | 88 (64.7) | 47 (34.6) | 1 (0.7) | 41 (30.1) | 95 (69.9) |

| 40-59 | 132 (72.9) | 49 (27.1) | 120 (66.3) | 57 (31.5) | 4 (2.2) | 56 (30.9) | 125 (69.1) |

| ≥60 | 105 (66.9) | 52 (33.1) | 114 (72.6) | 39 (24.8) | 4 (2.5) | 57 (36.3) | 100 (63.7) |

| p-value (Chi-Square) | 0.008* (11.77) | 0.454 (5.72) | 0.099 (6.27) |

| Gender |

| Male | 186 (75.0) | 62 (25.0) | 169 (68.1) | 78 (31.5) | 1 (0.4) | 100 (40.3) | 148 (59.7) |

| Female | 174 (73.4) | 63 (26.6) | 162 (68.4) | 67 (28.3) | 8 (3.4) | 61 (25.7) | 176 (74.3) |

| p-value (Chi-Square) | 0.690 (0.16) | 0.045* (6.18) | 0.001* (11.62) |

| Educational status |

| No formal education | 69 (60.0) | 46 (40.0) | 86 (74.8) | 26 (22.6) | 3 (2.6) | 36 (31.3) | 79 (68.7) |

| Primary | 104 (74.3) | 36 (25.7) | 99 (70.7) | 38 (27.1) | 3 (2.1) | 47 (33.6) | 93 (66.4) |

| Matric | 100 (79.4) | 26 (20.6) | 86 (68.3) | 38 (30.2) | 2 (1.6) | 40 (31.7) | 86 (68.3) |

| Senior secondary | 52 (83.9) | 10 (16.1) | 40 (64.5) | 21 (33.9) | 1 (1.6) | 22 (35.5) | 40 (64.5) |

| Graduate and above | 35 (83.3) | 7 (16.7) | 20 (47.6) | 22 (52.4) | - | 16 (38.1) | 26 (61.9) |

| p-value (Chi-Square) | <0.001* (18.74) | 0.066 (14.68) | 0.922 (0.91) |

| Occupational status |

| Home maker | 141 (73.4) | 51 (26.6) | 134 (69.8) | 52 (27.1) | 6 (3.1) | 50 (26.0) | 142 (74.0) |

| Service | 52 (78.8) | 14 (21.2) | 37 (56.1) | 28 (42.4) | 1 (1.5) | 23 (34.8) | 43 (65.2) |

| Business | 43 (84.3) | 8 (15.7) | 32 (62.7) | 18 (35.3) | 1 (2.0) | 18 (35.3) | 33 (64.7) |

| Farmer | 31 (66.0) | 16 (34.0) | 34 (72.3) | 13 (27.7) | - | 17 (36.2) | 30 (63.8) |

| Skilled/Unskilled worker | 41 (78.8) | 11 (21.2) | 39 (75.0) | 12 (23.1) | 1 (1.9) | 23 (44.2) | 29 (55.8) |

| Student | 9 (75.0) | 3 (25.0) | 6 (50.0) | 6 (50.0) | - | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) |

| Unemployed | 43 (66.2) | 22 (33.8) | 49 (75.4) | 16 (24.6) | - | 23 (35.4) | 42 (64.6) |

| p-value (Chi-Square) | 0.240 (7.97) | 0.249 (14.86) | 0.082 (11.22) |

| Marital status |

| Married | 281 (73.8) | 100 (26.2) | 262 (68.8) | 112 (29.4) | 7 (1.8) | 124 (32.5) | 257 (67.5) |

| Never married | 49 (87.5) | 7 (12.5) | 30 (53.6) | 25 (44.6) | 1 (1.8) | 19 (33.9) | 37 (66.1) |

| Widow/Widower/Divorced | 30 (62.5) | 18 (37.5) | 39 (81.2) | 8 (16.7) | 1 (2.1) | 18 (37.5) | 30 (62.5) |

| p-value (Chi-Square) | 0.013* (8.65) | 0.042* (9.90) | 0.784 (0.49) |

| II. Knowledge score (SD) | 10.9 (1.9) | 9.7 (2.6) | 10.4 (2.2) | 11.2 (1.9) | 8.4 (2.2) | 10.7 | 10.6 |

| p-value (F/t value) | <0.001** (4.786)†† | <0.001** (11.448)† | 0.916 (0.106)†† |

SD: Standard deviation; †One-way ANOVA test: ‘F; ††Independent sampled t test: “t; p<0.05* statistically significant; p<0.001** statistically highly significant

Discussion

This health centre based study offered insights into earlier days of COVID-19 pandemic in the rural Punjab, India and assessed knowledge, perceptions and practices of the patients. In the present study mean knowledge score was observed to be 10.6±2.1. The score rate was observed to be 70.7% during the initial phase of COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, Narayana G et al., in a study conducted among general public in India also observed that 74.7% participants had correct knowledge about COVID-19 [9]. Other studies conducted by Zhong B et al., in China (90.0%), Azlan AA et al., in Malaysia (80.5%) and Olum R et al., in Uganda (82.4%) observed higher knowledge of participants about COVID-19 [12-14]. Some of the variation could be due to the difference in study settings, participants, data collection methods and knowledge measurement. Regular dissemination of public information by health authorities started very early in India and this effort could have contributed to the knowledge of the study participants.

Regarding knowledge about symptoms, majority of the participants (87.6%) knew about main clinical symptoms in the present study, however shortness of breath was known to only 40% of the participants. Similar observation was reported by Narayana G et al., Dkhar SA et al., and Tandon T et al., in India wherein majority of the participants knew about main clinical symptoms of COVID-19 [9,10,15]. Austrian K et al., in Nairobi, Kenya observed that awareness about difficulty in breathing was known to 42% of respondents [16]. In the present study, 284 (58.6%) participants knew respiratory droplets as the route of transmission. However, other studies from Narayanan G et al., (90.8%) and Tandon T et al., (95%) in India [9,15] and Zhong B et al., in China (97.8%), Azlan AA et al., in Malaysia (81.9%) and Kebede Y et al., in Ethiopia (95.1%) reported higher level of knowledge regarding transmission through respiratory droplets [12,13,17]. As seen in previous studies by Narayana G et al., and Tandon T et al., in India [9,15] and Zhong B et al., in China, Azlan AA et al., in Malaysia, Olum R et al., in Uganda and Austrian K et al., in Nairobi, Kenya [12-14,16], majority of the participants in the present study were well aware about consistent use of facemasks (97.3%) and isolation and treatment of infected individuals (92.4%) as the effective ways to reduce the infection. Regular education of residents regarding wearing of mask was the important practice adopted by health authorities and moreover, wearing of masks was made compulsory by Government [18], which indeed helped to raise the awareness.

Educational levels had significant positive association with COVID-19 knowledge scores as reported by Narayana G et al., in India and Zhong B et al., in China [9,12]. The current study also identified that education was an important factor independently associated with knowledge score of the participants. Kebede Y et al., in Ethiopia (secondary school and above vs. non-attenders, p<0.01) reported similar association of education with knowledge [17]. Akalu Y et al., in Ethiopia observed that educational status of can’t and write vs. secondary and above were significantly associated with poor knowledge (p<0.05) [19]. Rahman A and Sathi NJ, in Bangladesh (Bachelor and higher vs. higher secondary, p<0.05) also reported association similar to current study in education levels with knowledge [20]. In the current study, television (79.8%) was the main source of COVID-19 information for the participants. Similarly, Narayana G et al., and Tandon T et al., in India reported television (74.5%) and television news channels (61.6%) [9,15] and Austrian K et al., in Nairobi, Kenya reported Government TV advertisements (85.9%) to be the most common and trustworthy source of information [16]. Also, national television channel aired famous popular old and religious serials with health education on COVID-19 in between breaks during lockdown in India.

The present study revealed perceived stigma by nearly 40% of the participants against COVID-19 infected persons, their contacts and those returned from COVID affected areas [21]. Overall, 283 (58.4%) participants were feeling low due to COVID-19 or restrictions. Kebede Y et al., in Southwest Ethiopia also reported presence of perceived stigma [17]. Application of social media and technology during COVID-19 pandemic may spread misinformation and may instead increase stigma and dilute public health gains achieved [22]. Although there was regular dissemination of factual information of COVID-19 to the community on television (79.8%) as it was evident from the present study, still the spread of misinformation through social media might have led to perceived social stigma [22]. As also recommended by WHO, choice of terminology during such times has to be used carefully giving a clear message rather than confusion [23]. Frequent use of term social distancing could also have been interpreted wrongly by some community members as to socially distance from the infected individuals and was later being used with more appropriate word physical distancing.

Knowledge about handwashing as an effective method of prevention was also reflected in the practices being followed by the participants in the present study, wherein 360 (74.2%) of the participants followed handwashing. Other studies conducted by Narayana G et al., (98.2%) Dkhar SA et al., (87.0%) and Tandon T et al., (97.8%) in India [9,10,15] and Azlan AA et al., in Malaysia (87.8%), Olum R et al., in Uganda (74.0%), Kebede Y et al., in Ethiopia (77.3%), Rahman A and Sathi NJ, in Bangladesh (98.6%), Lau LL et al., in Philippines (82.2%) and Muto K et al., in Japan (86.0%) also reported frequent handwashing as the predominant preventive practice carried out by the participants [13,14,17,20,24,25]. Higher knowledge score was significantly associated with regular handwashing practices (p<0.001). As seen in previous studies by Narayana G et al., (97.1%), Dkhar SA et al., (73.0%) and Tandon T et al., (85.0%) in India [9,10,15] and Zhong B et al., in China (98.0%), Rahman A and Sathi NJ, in Bangladesh (91.4%), Reuben RC et al., in Nigeria (82.3%) [12,20,26], majority of participants wore facemask in terms of either cloth face-cover (68.2%) or three layered masks (29.9%). This is also corroborated by the results of Akalu Y et al., in Ethiopia, wherein about 78% of the subjects wore reusable masks [19]. Possible explanation for higher use of cloth face-cover over three layered masks in the present study could be due to the shortage of three layered masks during early days of pandemic [27,28]. Therefore, to ensure that public should wear at least cloth face-cover, rather than not wearing any mask, regular messages were spread on television, radio and social media platforms which were given by politicians and officials to wear cloth face-cover (popularly named ‘Gamchha’ in vernacular language) [5,28].

In the current study, only 161 (33.2%) of the participants followed physical distancing. This is in concordance with the finding by Akalu Y et al., in Ethiopia wherein physical distancing (29.9%) was the least practiced preventive measure [19]. Lau LL et al., in Philippines reported that 65.9% of the respondents maintained a distance from persons with influenza like symptoms [24] and in contrast Narayana G et al., Dkhar SA et al., and Tandon T et al., in India reported that most of the participants (96.9%, 87.0% and 97.5%, respectively) were following physical distancing [9,10,15].

Limitation(s)

Knowledge questionnaire used in the study was adapted from previously tested surveys [11,12], although thorough estimation of its validity and reliability could have led to the development of an improved questionnaire. The assessment of practices was self-reported by participants instead of observing them might have produced biased results, as the participants could have responded more in favour of socially acceptable practices. Also, the study participants had come for OPD consultation and this might have made them more aware of COVID-19 infection.

Conclusion(s)

The present study gives an insight into knowledge, perceptions and practices of rural community regarding COVID-19 infection during early stage of lockdown period. Mean knowledge score of study participants was above average. Young and educated participants had higher knowledge score and followed preventive practices more religiously in comparison to their counterparts. Majority of the participants knew about clinical symptoms and preventive practices. Handwashing was the most common practice followed. Most of the participants agreed that this disease generates social stigma. This study also helps to identify target groups for intervention for increasing knowledge, perception and practices regarding COVID-19 infection.

SD: Standard deviation; †One-way ANOVA test(F); ††Independent sample t-test (t); p<0.05* statistically significant; p<0.001** statistically highly significant

Multiple linear regression test using stepwise method; CI: Confidence interval p<0.05* statistically significant; p<0.001** statistically highly significant

SD: Standard deviation; †One-way ANOVA test: F; p<0.05* statistically significant; p<0.001** statistically highly significant

SD: Standard deviation; †One-way ANOVA test: ‘F; ††Independent sampled t test: “t; p<0.05* statistically significant; p<0.001** statistically highly significant