Imaging evaluation of thoracic tumours gives information on the extent of tumour involvement, potential for resectability and its response to therapy [1]. Routine radiological evaluation includes conventional radiography and computed tomography. Chest X-ray is a rather insensitive imaging modality for thoracic tumours. In routine clinical practice, CT is the most common cost effective imaging modality applied for the evaluation of intra-thoracic masses. CT helps in staging, characterisation and prognostic evaluation of mass lesions and thus, alerts the clinicians and radiologists about a malignancy [2]. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), can be better informative in certain conditions like to look for chest wall soft tissue details, mediastinal involvement or to determine neurogenic origin of masses [3].

Bronchogenic carcinomas constitute a major bulk of the common thoracic tumours presenting mostly when small in size due to their central location or early metastasis [4]. However, in some cases, they may present at a larger size and may then have to be differentiated from uncommon intra-thoracic masses which mostly present when large in size and show no signs of invasion/metastasis.

It is important to note that the imaging appearances of common and uncommon thoracic tumours exhibit considerable overlap. Hence, the diagnosis of an unusual lung tumour is mostly made retrospectively from a biopsy report [4]. In this study, we aim to demonstrate characteristic CT features of large common and certain uncommon intra-thoracic masses along with their histopathology correlation. We further wish to encourage co-radiologists to include these tumours in differential diagnoses apart from the common ones by identifying their characteristic CT features which has practical implications for patient management and prognosis including deterring unnecessary surgeries.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective cross-sectional data analysis was done on archives of patient record in Radiology Department from December 2017 to January 2019 for intra-thoracic tumours. Study was conducted in January 2020 in SMS Medical College and Hospital, Jaipur, Rajasthan. Since this study involves secondary data analysis, calculation of sample size was not required and all patients meeting the inclusion criteria were treated as sample size. Moreover, since it is a retrospective non-interventional study with treatment of all the patients completed before start of the study, consent was waived-off.

Inclusion criteria: All cases having large intra-thoracic masses (>7 cm in widest dimension on CT scan) and all cases having contrast enhanced CT chest scans and whose histopathology reports were traceable were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria: All cases having masses of cardiac/pericardial or mediastinal origin and those cases who had received neo-adjuvant therapy prior to scanning, were excluded from the study.

Out of total 44 selected cases, 23 cases have been found to meet the above mentioned criteria. All the included chest CT scans were reviewed consensually by two experienced radiologists. Both were blinded about the histopathology reports. All lesions were confirmed to be intra-thoracic and >7 cm and then following information was collected about each one of them- location, shape, margins, enhancement pattern, cavitation, calcification, presence/absence of necrosis, intra-lesional vessels, associated pleural/pericardial effusion, suspect lymphadenopathy and rib involvement [Table/Fig-1].

Imaging characteristics of masses.

| S. No. | Final diagnoses | Shape | Size (cm) | Margin | Add. features and pressure effect | Enhancement pattern | Cavitation/Necrosis/Intra-lesional vessels | Calcification | LAP | Effusion | Rib change |

|---|

| 1. | Pulmonary blastoma | Round | 15×13 | Smooth and lobulated | Inverted dome and cardiac shifting | Heterogenous and Intense | Necrosis (+++) | - | - | - | - |

| 2. | Askin’s tumour | Round | 12×8 | Smooth and lobulated | No mass effect | Homogenous and moderate | Minimal necrosis | Ring like coarse calcification | - | Mild left pleural and pericardial | Left 4th rib destruction |

| 3. | Mucinous adenocarcinoma metastasis | Ovoid | 15×11 | Smooth | Opaque hemithorax | Heterogenous intense peripheral and septal | Necrosis (+++) | Coarse calcification | - | Minimal left pleural and mild pericardial | - |

| 4. | Synovial Sarcoma | Round | 10×10 | Smooth | Lower lung mild cardiac shifting | Intense heterogenous with shaggy inner margins | Necrosis (+++) and large intra-lesional vessels | - | - | Mild left pleural and pericardial | - |

| 5. | Squamous cell carcinoma | Irregular | 12×9 | Undefine | Central | Heterogenous | Necrosis(+++) | - | - | - | - |

| 6. | Adenocarcinoma | Oval | 9×7 | Smooth | No mass effect | Heterogenous | Mild necrosis | Absent within the lesion | + | Minimal right pleural | - |

| 7. | Adenocarcinoma | Round | 9.5×9.0 | Smooth | No mass effect | Heterogenous | Mild necrosis | - | + | - | - |

| 8. | Adenocarcinoma | Round | 9.0×8.5 | Smooth | No mass effect | Heterogenous | Significant necrosis | - | + | Minimal left pleural | - |

| 9. | Synovial sarcoma | Round | 14×14 | Smooth | Cardiac shifting | Heterogenous predominantly peripheral intense with shaggy margin | Large areas of necrosis with intra-tumoural vessels | - | - | Minimal left trapped pleural effusion | - |

| 10 | SFT | Round | 13.5×13 | Smooth and lobulated | Lower lung and diaphragmatic flattening | Solid, mild heterogenous | Small necrotic areas | Tiny foci of calcification | - | - | - |

| 11. | Askin’s tumour | Oval | 30×25 | Smooth | Cardiac shifting and diaphragmatic inversion | Heterogenous and intense with shaggy inner margins | Necrosis (+++) | - | - | - | Left 5th rib destruction |

| 12. | Schwannoma | Round | 11×11 | Smooth | Paravertebral | Homogenous | - | Speck of calcification at periphery | - | - | - |

| 13. | Squamous cell carcinoma | Irregular and spiculated | 11×9.0 | Undefine | Centrally located with distal collapse | Heterogenous | Necrosis and cavitation + | - | - | Mild right pleural effusion | - |

| 14. | Squamous cell carcinoma | Irregular | 8.5×7.5 | Undefine | Mid lung zone | Heterogenous | + | - | + | Minimal right pleural effusion | - |

| 15. | Squamous cell carcinoma | Round | 7.5×7.0 | Lobulated | Peripheral | Heterogenous | Cavitation + | _ | + | Mild right pleural effusion | - |

| 16. | Small cell carcinoma | Irregular | 10×9.0 | Undefine | Central with distal collapse | Heterogenous | + | - | + | Minimal right pleural effusion | - |

| 17. | Synovial sarcoma | Round | 9.0×9.0 | Smooth and well defined | Lower lung and cardiac shifting | Heterogenous | Necrosis with intra-tumoural vessels | _ | _ | Mild left pleural effusion | - |

| 18. | Pulmonary blastoma | Round | 14×13.5 | Smooth and lobulated | | Heterogenous | + | _ | + | _ | - |

| 19. | Large cell carcinoma | Oval | 14×10 | Undefine | | Heterogenous | + | - | - | - | - |

| 20. | Adenocarcinoma | Irregular | 11×10 | Smooth | | Heterogenous | - | - | + | Minimal left pleural and pericardial effusion | - |

| 21. | Large cell carcinoma | Oval | 11.3×10.5 | Smooth | Peripheral | Heterogenous | + | - | + | - | - |

| 22. | Small cell carcinoma | Irregular | 8.6×8.0 | Undefine | Central | Heterogenous | Few necrotic areas | + | + | Moderate left pleural effusion | _ |

| 23 | SFT | Round | 12×11 | Smooth | Lower lung no mass effect | Heterogenous | + | _ | _ | Minimal left pleural effusion | - |

Necrosis (+++)-extensive, SFT: Solitary fibrous tumour; Add.: Additional; LAP: Lymphadenopathy

A probable radiological diagnosis was consensually reached for each case and it was correlated with the histopathology report to reach a confirmed diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

The unique CT features mentioned in the above list were separately tabulated and p-value for a particular diagnosis was calculated using Fisher’s-exact test. The statistical analysis was done using statistical software SPSS for windows (version 16).

Results

Among the 23 patients studied, 13 were males and 10 were females. Mean age was 44 years (44±10.67 years), ranging from 3-70 years. Core biopsy of all the patients was done in Radiology Department.

Among all the masses studied, 15 (65.22%) had their origin from the lungs, 2 (8.70%) were from pleura, 2 (8.70%) were from chest wall and rest 4 (17.39%) were indeterminate in origin.

The most predominant margin was smooth and lobulated (17 i.e., 73.91%). Most of the masses originating in the lungs, were showing heterogenous density with presence of necrosis (21 out of 23 i.e., 91.30%). Most of them had associated minimal to mild pleural effusion (14 out of 23 i.e., 60.87%). Calcification was seen only in 5 patients (Sr. No. 2,3,10,12,22) (21.74%). Intra-tumoural vessels were seen in 3 lung masses [Table/Fig-1,2 and 3].

Baseline characteristics of subjects including their probable CT diagnosis and final HPE diagnosis.

| S. No | Age (years) | Sex | Probable diagnosis on CT | Location | Side | Final HPE diagnosis |

|---|

| 1. | 65 | M | Bronchogenic neoplasm likely non-small cell carcinoma | Lung | L | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| 2. | 62 | M | Bronchogenic neoplasm likely squamous cell carcinoma | Lung | R | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| 3. | 58 | M | Bronchogenic neoplasm likely squamous cell carcinoma | Lung | R | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| 4. | 63 | M | Bronchogenic neoplasm likely non-small cell carcinoma | Lung | R | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| 5. | 54 | F | Bronchogenic neoplasm likely non-small cell carcinoma | Lung | L | Adenocarcinoma |

| 6. | 70 | F | Bronchogenic neoplasm likely non-small cell carcinoma | Lung | R | Adenocarcinoma |

| 7. | 42 | M | Bronchogenic neoplasm likely non-small cell carcinoma | Lung | L | Adenocarcinoma |

| 8. | 65 | M | Bronchogenic neoplasm likely non-small cell carcinoma | Lung | L | Adenocarcinoma |

| 9. | 59 | M | Bronchogenic neoplasm likely small cell carcinoma | Lung | R | Small cell carcinoma |

| 10. | 63 | M | Bronchogenic neoplasm likely small cell carcinoma | Lung | L | Small cell carcinoma |

| 11. | 65 | M | Bronchogenic neoplasm likely non-small cell carcinoma | Lung | R | Large cell carcinoma |

| 12. | 66 | M | Bronchogenic neoplasm likely non-small cell carcinoma | Lung | R | Large cell carcinoma |

| 13. | 3 | M | Pulmonary blastoma | Lung | R | Pulmonary blastoma |

| 14. | 6 | M | Pulmonary blastoma | Lung | R | Pulmonary blastoma |

| 15. | 36 | F | Neoplastic lesion | Lung | L | Mucinous adenocarcinoma metastasis |

| 16. | 20 | F | Mesenchymal neoplasm likely sarcoma | Lung/pleura* | L | Synovial sarcoma |

| 17. | 21 | F | Mesenchymal neoplasm likely sarcoma | Lung/pleura* | L | Synovial sarcoma |

| 18. | 22 | F | Mesenchymal neoplasm likely sarcoma | Lung/pleura* | L | Synovial sarcoma |

| 19. | 16 | F | Askin’s tumour | Chest wall (left 5th rib)* | L | Askin’s tumour |

| 20. | 9 | M | Askin’s tumour | Chest wall (left 4th rib)* | L | Askin’s tumour |

| 21. | 55 | F | Benign mesenchymal neoplasm | Pleura/chest wall* | L | Schwannoma |

| 22. | 45 | F | Pleural based neoplasm possibly SFT | Pleura | R | Solitary fibrous tumour |

| 23. | 47 | F | Pleural based neoplasm possibly SFT | Pleura | L | Solitary fibrous tumour |

*Masses with indeterminate origin

HPE: Histopathological examination; CT: Computed tomography; M: Male; F: Female; R: Right; L: Left; SFT: Solitary fibrous tumour

Spectrum of CT findings of lung masses along with their relative frequencies.

| CT findings | No. of tumours | Percentage |

|---|

| Location |

| LungChest wallPleuraIndeterminate | 15224 | 65.22%8.70%8.70%17.39% |

| Margins |

| Smooth/LobulatedUndefined | 176 | 73.91%26.09% |

| Enhancement |

| HomogenousHeterogenousIntense | 2215 | 8.69%91.30%21.73% |

| Calcification | 5 | 21.74% |

| Pleural effusion | 14 | 60.87% |

| Intra-tumoural vessels | 3 | 13.04% |

| Chest wall/rib involvement | 2 | 8.69% |

| Intra-thoracic suspect lymph nodes | 10 | 43.48% |

CT: Computed tomography

Intra-tumoural vessels were found to be extremely significant for the diagnosis of synovial sarcoma [Table/Fig-4]. Both chest wall lesions were associated with subtle rib destruction suggesting osseous origin, later confirmed as Askin’s tumour on histopathology (Sr. No. 2 and 11) [Table/Fig-1]. This association of rib erosion with Askin’s tumour was found to be very statistically significant (p-value 0.004) [Table/Fig-5]. About 10 out of 23 (43.48%) masses had associated lymphadenopathy.

Statistical analysis of intra-lesional vascularity as a CT feature.

| CT diagnosis | Intra-lesional vascularity present | Intra-lesional vascularity absent | Total |

|---|

| Synovial sarcoma | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Others | 0 | 20 | 20 |

| Total | 3 | 20 | 23 |

p-value=0.0006 (Extremely statistically significant), calculated via Fischer’s-exact test

Statistical analysis of rib erosion as a CT feature.

| CT diagnosis | Rib erosion present | Rib erosion absent | Total |

|---|

| Askin’s tumour | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Others | 0 | 21 | 21 |

| Total | 2 | 21 | 23 |

p-value= 0.004 (Very statistically significant), calculated via Fischer’s-exact test

CT: Computed Tomography

None of the mass lesion centered in lung parenchyma had rib destruction. Two localised pleural based masses were diagnosed as solitary fibrous tumour on histopathology. About 4 out of 23 masses had indeterminate origin i.e., from lungs/pleura/chest wall, 3 of them proved as synovial sarcomas and 1 as schwannoma on histopathology [Table/Fig-2]. About 5 out of 23 (21.73%) cases had intense enhancement, all 5 tumours being non-bronchogenic in origin and this feature was found to be significantly associated for non-bronchogenic origin (p-value 0.0137) [Table/Fig-6].

Statistical analysis of intense enhancement as a CT feature.

| CT features | Intense enhancement present | Intense enhancement absent | Total |

|---|

| Non-bronchogenic | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| Bronchogenic | 0 | 12 | 12 |

| Total | 5 | 18 | 23 |

p-value=0.0137 (Statistically significant), calculated via Fischer’s-exact test

The baseline characteristics of subjects included their probable CT diagnosis and final HPE diagnosis. Out of total 4 squamous cell carcinoma on HPE, 2 were confidently diagnosed on CT scan due to presence of cavitation. Rest 2 were diagnosed as non-small cell bronchogenic neoplasm. All 4 adenocarcinomas and 2 large cell carcinomas were confidently diagnosed as bronchogenic non-small cell neoplasm owing to their large size and predominantly peripheral location. Both small cell carcinomas were diagnosed on CT scan confidently as they had typical features like central location and calcification.

Both pleuro-pulmonary blastomas were diagnosed confidently on CT scan due to their typical age of presentation and imaging features. All 3 synovial sarcomas were diagnosed as mesenchymal neoplasm-sarcomas on CT scan which were proven as synovial sarcomas on HPE. Metastasis from carcinoma colon was diagnosed as neoplastic lesion only on CT scan due to its atypical imaging and solitary lesion. Schwannoma was diagnosed as benign mesenchymal neoplasm on CT. Askin’s tumour were correctly diagnosed on CT due to its typical rib erosion feature. Both solitary fibrous tumours were suggested on CT due to pleural based neoplastic localised masses [Table/Fig-2].

Discussion

There are a wide variety of large thoracic tumours which present with imaging features mimicking those of the common varieties of bronchogenic carcinomas. On initial chest radiographs, these masses usually appear as an opaque hemithorax or an obvious large opaque mass. CT scan, however, remains the imaging modality of choice [3]. Moreover, the CT scanners are day by day becoming more sophisticated in design and versatility and hence, will surely remain the principal imaging modality for evaluation of thoracic masses in near future [5].

In the present study, out of all 23 large thoracic masses, 15 originated from lungs. Out of these 23, 12 were epithelial tumours arising from lung (4-squamous cell, 2-small cell, 4-adenocarcinomas and 2-large cell carcinoma), 10 were mesenchymal tumours (3 synovial cell sarcomas, 2-askin’s tumour, 2-solitary fibrous tumour, 2-pulmonary blastoma and 1-schwannoma) and 1 was metastasis from mucinous adenocarcinoma of colon.

Now taking each tumour independently, CT scan of the four squamous cell carcinoma cases showed heterogeneity due to the presence of necrosis, three of them showed undefined margins and one showed lobulated margins. Although cavitation is an important feature of squamous cell carcinoma [5], this feature was seen in only two out of four cases in this study. Three out of four cases had associated pleural effusion. Suspect lymph nodes were present in two cases. In the present study, complete lung collapse was seen in one centrally located cavitating tumour which later proved to be squamous cell carcinoma on histopathology. One of the cases also had additional large necrotic well defined nodule in the opposite lung.

The CT of four adenocarcinomas included in the study showed large smoothly marginated peripherally located heterogenous necrotic masses with associated lymphadenopathy in all and minimal effusion present in three cases.

Small cell carcinoma was found in two cases. On CT scan, one of them had centrally located large calcified mass with distal collapse, pleural effusion and hilar/mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The other one showed left pleural effusion, large confluent mediastinal lymphadenopathy with left hilar involvement having internal calcification. Intra-tumoural calcification has also been described in up to 23% patients with small cell carcinoma in a study done by Carter BW et al., [6].

Large cell carcinomas were found in two cases. They showed non-specific findings on CT scan including large heterogenous well defined masses with no effusion. However, one of them had suspected mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Similar findings of having large heterogenous masses with/without lymphadenopathy have also been observed by Hollings N and Shaw P [5].

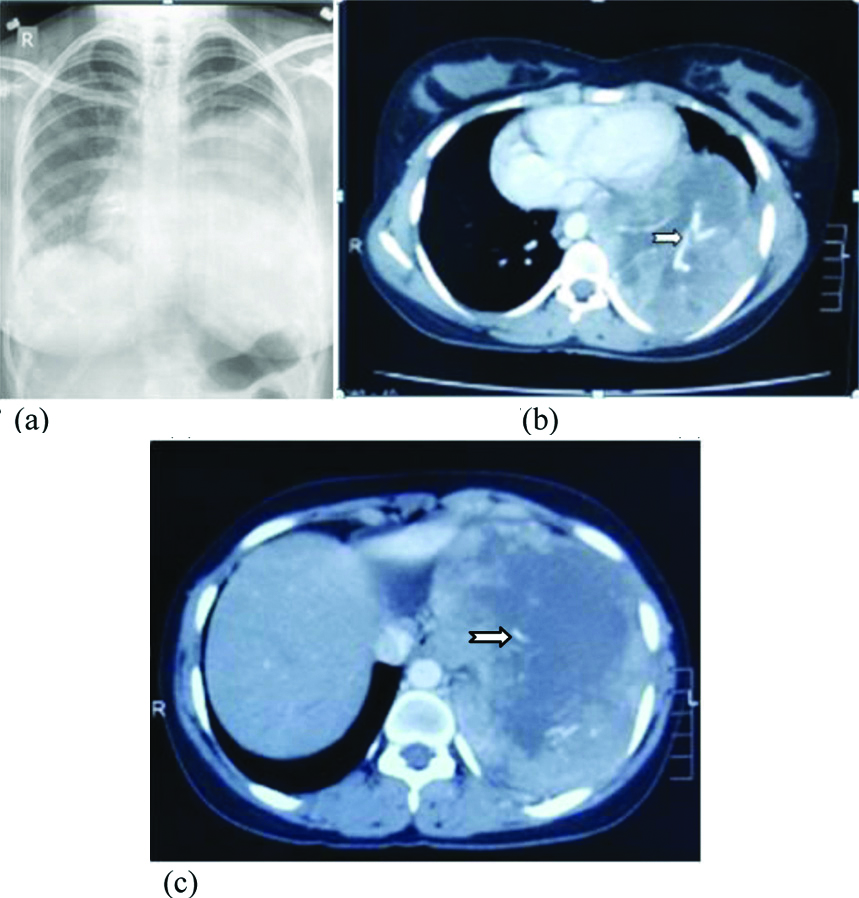

There were three cases of pleuro-pulmonary synovial sarcoma of the chest in the present study originating either in lung or pleura. Majority of the cases reported in literature as pleuro-pulmonary synovial sarcoma had peripheral/parafissural location with an uncertain origin from pleura/lung due to large size [7]. Same was true for all three cases in this study. All of them further showed relatively homogenous large opacity on chest X-ray with contralateral mediastinal shifting and no obvious bony erosion/lymphadenopathy, while on CT scan, all cases had large heterogenous masses with extensive necrosis and peripheral enhancement with septations and large intra-lesional vessels. Intra-tumoural vessels were found as a very common internal feature (92.9%) in a study done by Kim GH et al., [8]. All of them had ipsilateral minimal to mild pleural effusion with contralateral mediastinal shifting. None of them had calcification/suspect lymphadenopathy or thoracic wall invasion [Table/Fig-7].

Synovial sarcoma in 20-year-old female. (a). Chest skiagram showing large round opacity in left mid and lower zones with mild right sided cardiac shifting.(b) and (c) Axial contrast enhanced CT scans showing large intensely enhancing necrotic soft tissue density mass lesion with prominent intra-lesional vessels.

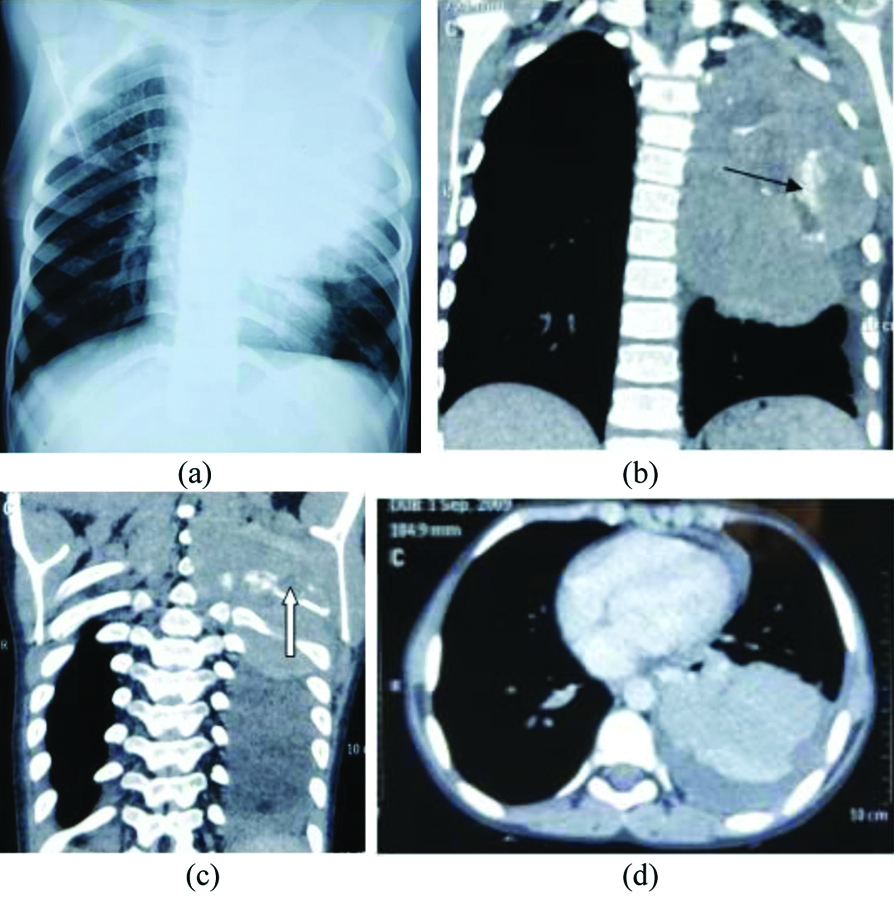

Two cases diagnosed as Askin’s tumour presented as opaque hemithorax on chest X-ray and large extrapulmonary masses with solitary rib destruction on CT scan. One of them had predominantly homogenous enhancement, internal calcification as well as pleural effusion. Other showed heterogenous enhancement with extensive necrosis and contralateral mediastinal shifting. None of them had lymphadenopathy. Solitary rib destruction is a rather specific feature, present in 25-63% cases [9]. Subtle bony changes are sometimes very difficult to identify on chest X-rays so CT scan is a must to pick up this key feature of Askin’s tumour [Table/Fig-8] [10].

Askin’s tumour in nine-year-old male child. (a) Chest skiagram showing large homogenous round opacity in left upper and mid zones.(b) and (c) Coronal contrast enhanced CT scans showing large intensely enhancing homogenous soft tissue density mass with lobulated margins in left hemithorax having minimal necrotic component, coarse calcification (black arrow) and associated destruction of left 4th rib (white arrow), not evident in skiagram even in retrospect.(d) Axial contrast enhanced CT scans show soft tissue density solid lesion, also note mild left pleural and pericardial effusion.

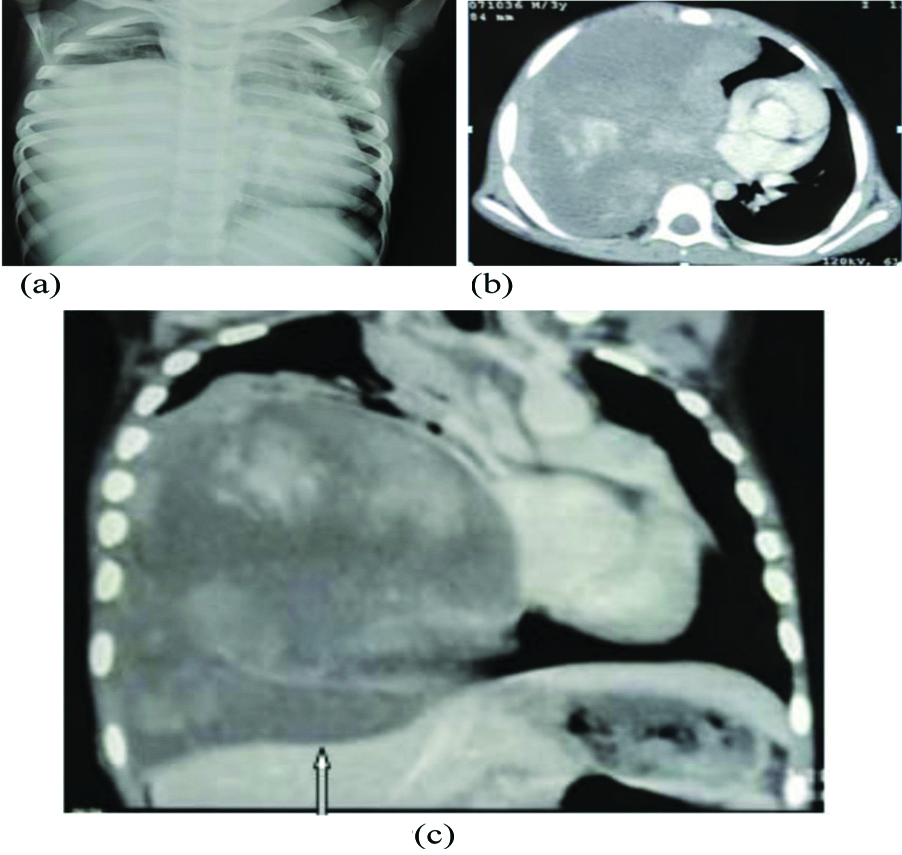

Two cases of pulmonary blastoma in young children, showed large heterogenous solid-cystic mass lesions with adjacent lung atelectesis and no effusion or rib changes on CT scan. These features were though non-specific but matched closely with those mentioned by Khan AA et al., [Table/Fig-9] [11].

Pulmonary blastoma in three-year-old male child. (a) Chest skiagram showing large homogenous opacity in right mid and lower zones with left sided mediastinal shifting. (b) and (c). Axial and coronal contrast enhanced CT scans showing large intensely enhancing heterogenous soft tissue density mass with extensive necrosis in right hemithorax and mass effect as evidenced by diaphragmatic flattening(white arrow) and left sided mediastinal shifting.

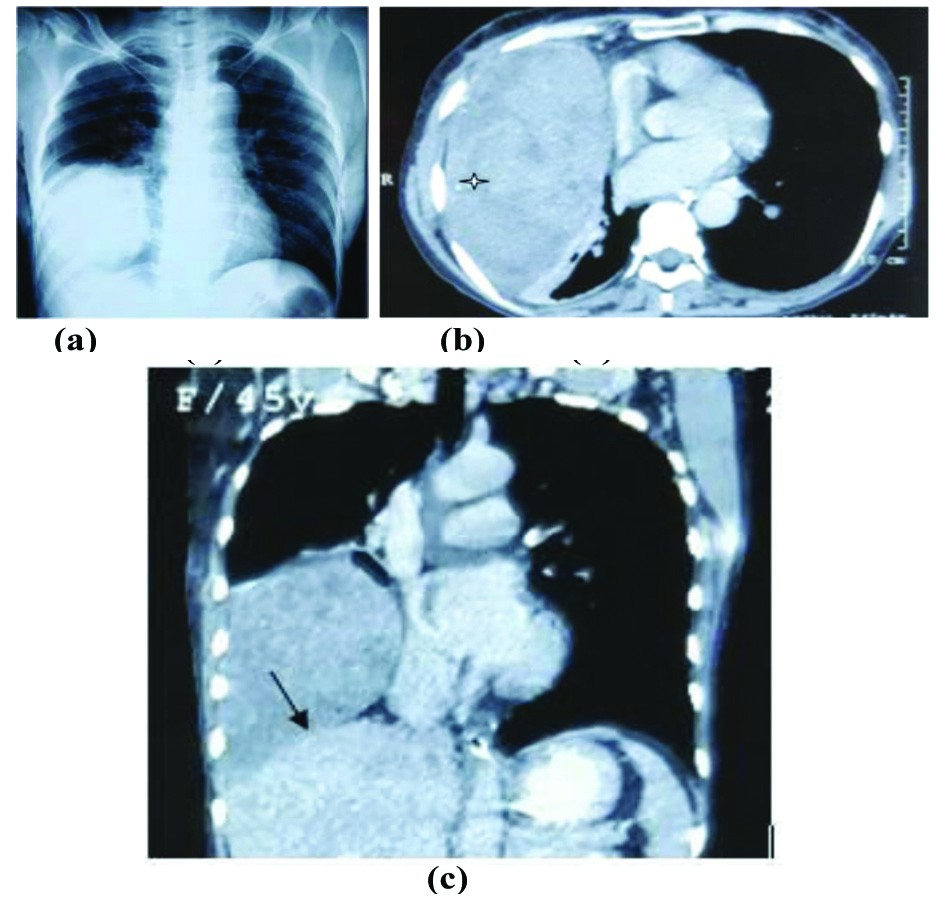

Two pleural lesions have been included in the study having features typical of solitary fibrous tumours i.e., peripheral location, heterogenous solid masses with minimal effusion and no calcification/rib changes on CT scan. Literature has described homogeneity in smaller tumours and heterogeneity appearing with increasing size in larger lesions due to haemorrhage and necrosis [Table/Fig-10] [12].

Solitary fibrous tumour in 44-year-old female. (a). Chest skiagram showing large round opacity in right lower zone.(b) and (c) Axial and coronal contrast enhanced CT scans showing heterogenous soft tissue density mass lesion in right hemithorax showing small necrotic areas and few foci of calcification, no effusion present. Mass effect of solid lesion is evident as diaphragmatic flattening on coronal images (black arrow).

Another large mass with unusual diagnosis on histopathology was Schwannoma. The CT scan showed all non-specific features like smoothly marginated homogenous extrapulmonary mass lesion in left apical region, with speck of calcification at periphery and no associated pleural effusion/bony changes. Patient further underwent contrast MRI for soft tissue characterisation. Similar findings has also been reported in literature by Ravikanth R [13,14]

Intense enhancing component on CT scan was yet another characteristic feature which was significantly associated with non-bronchogenic tumours.

Finally, the mass with most unusual diagnosis on histopathology was solitary metastasis from mucinous adenocarcinoma of colon whose CT scan showed large heterogenous mass having coarse calcification and cystic component alongwith complete atelectesis of ipsilateral lung and minimal pleural effusion. This was not confidently diagnosed as metastasis on imaging owing to its unusual imaging pattern i.e., large size and solitary lesion, although previous literature has also mentioned a whole spectrum of unusual findings on CT for lung metastases including those found in the case included in this study [Table/Fig-11] [15].

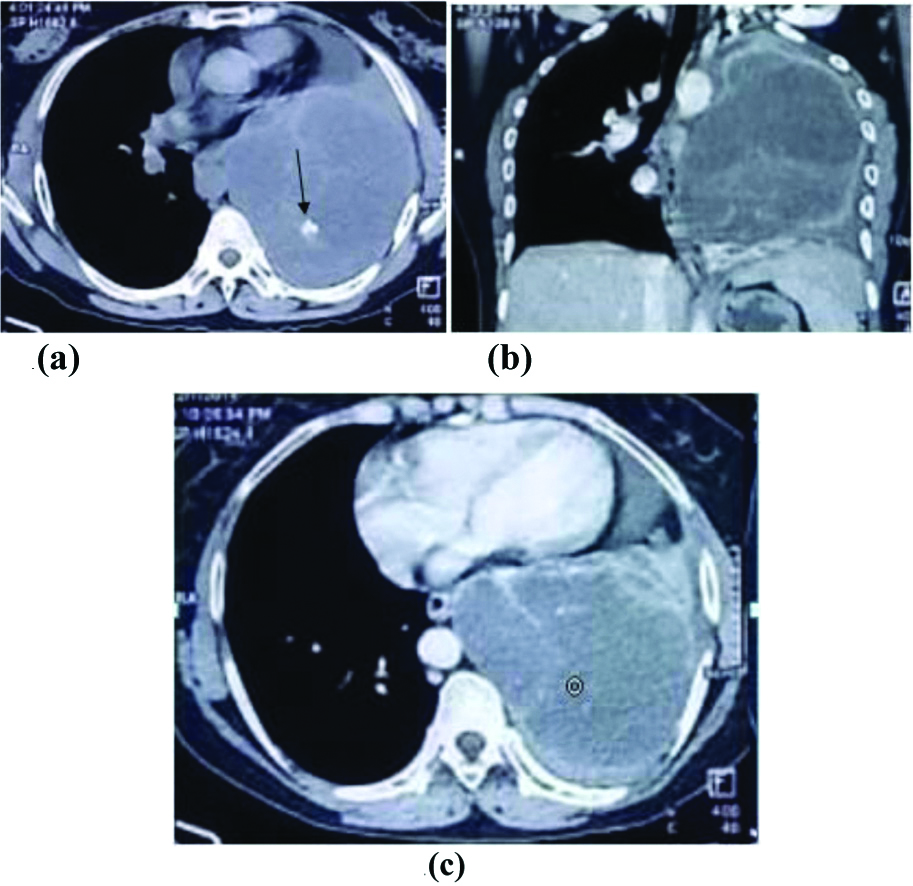

Solitary metastasis in thirty six-year-old female (known case of mucinous carcinoma of colon). (a). Non contrast CT scan showing large heterogenous mass lesion in left hemithorax with coarse calcific focus (black arrow). (b) and (c) Axial and Coronal contrast enhanced CT scans showing large intensely predominantly peripherally enhancing soft tissue density mass with cystic component and associated minimal left pleural and mild pericardial effusion.

Limitation(s)

Limitations of this study are that it is single institute study with a small sample size. So, the conclusions drawn need to be validated by larger studies before applying it to the general population.

Conclusion(s)

Thus, to conclude, it can be safely suggested that on encountering an opaque hemithorax on chest X-ray and a large mass on CT (with no signs of local invasion or significant pleural effusion or distant metastasis), one should specifically look for some salient characteristic imaging features like the presence of intra-tumoural vessels, subtle rib destruction, coarse calcification, intensely enhancing soft tissue component on CT scan. These imaging characteristics if present, may alert us towards an uncommon diagnosis which may be suggested right away at imaging, while histopathology report is still being awaited. This study however, paves way for future study and research and tends to encourage radiologists to keep unusual and less frequent yet very important differentials in day to day clinical practice.

Necrosis (+++)-extensive, SFT: Solitary fibrous tumour; Add.: Additional; LAP: Lymphadenopathy

*Masses with indeterminate origin

HPE: Histopathological examination; CT: Computed tomography; M: Male; F: Female; R: Right; L: Left; SFT: Solitary fibrous tumour

CT: Computed tomography

p-value=0.0006 (Extremely statistically significant), calculated via Fischer’s-exact test

p-value= 0.004 (Very statistically significant), calculated via Fischer’s-exact test

CT: Computed Tomography

p-value=0.0137 (Statistically significant), calculated via Fischer’s-exact test