Evidence is emerging of the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency as reflected by low 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels among Indians predisposing them to bone mineral metabolic imbalance. Skin pigmentation, cultural habits causing little sun exposure, dietary factors, pollution have been suggested as possible reasons for the deficiency [1-5]. Systematic reviews have found a relationship between insufficient 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels during pregnancy and adverse outcomes for mothers as well as neonates [6,7]. Vitamin D deficiency screening is not a part of routine antenatal screening in India and data is needed from various regions of the country to understand the magnitude of the problem and devise appropriate mitigation strategies. The present study evaluates the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among pregnant mothers and their newborns at a hospital in Mumbai catering to the affluent population from the region.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was done at the Department of Paediatrics and Neonatology at Lilavati Hospital and Research Centre in Mumbai. Latitude of Mumbai is 18° North. Study was done from August to November 2012 i.e., monsoon and winter months.

Sample size of 85 was estimated for finding a correlation of 0.3 and above between maternal and newborns vitamin D levels with 80% power of study at 5% alpha error. A 100 women and their newborns who were delivered at the hospital were included in this cross-sectional study. All the subjects gave informed consent for the enrollment. The study design was approved by the Ethics committee at Lilavati Hospital and Research Centre, Mumbai (vide letter J5272 dated 14 August 2012).

Mothers of Indian origin, between 20-45 years of age with no history of any chronic disease or long-term treatment with drugs in the previous three months were included. Pregnant women with associated medical conditions such as Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension (PIH), Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM), hypothyroidism were excluded from the study. The study included newborns of these mothers with completed 35 weeks of gestation who were healthy and did not required intensive care.

The demographic history such as name, age, height, weight and religion of mothers was documented. The obstetric history of all mothers included the type of conception, parity, calculated gestational age and number of abortions. The mothers reported whether they received any calcium and vitamin D supplements (apart from that incorporated in routine calcium formulations) during the pregnancy. Mothers also reported about the average daily hours of sun exposure, diet (vegetarian/non-vegetarian). We recorded the birth weight of newborns in kilograms, the length in centimetres, head circumference in centimetres on day 4. The weight was measured with a standard weighing scale and length by infantometer. The head circumference was measured with a measuring tape. Each woman delivered between 35 and 41 weeks of gestation after an uneventful pregnancy and gave birth to a singleton infant by spontaneous vaginal delivery or lower segment caesarean section. Gestational age was estimated by the date of the last menstrual period in weeks and days.

A sample of venous blood was taken from each woman at the time of vaginal delivery/lower segment caesarean section for the determination of serum calcium, 25 (OH) vitamin D, albumin concentration. Also, a sample of venous cord blood was taken from the infant for determination of serum calcium, 25 (OH) vitamin D, and albumin concentration.

Biochemical Measurements

All blood samples were centrifuged within an hour after collection. Plasma was separated and processed for analysis. The serum 25 (OH) Vitamin D was measured with Elecsys and Cobas C (Roche/Hitachi) immunoassay analyser using Electro-Chemiluminescence Immunoassay (ECLIA) method for assessing Vitamin D level. The measuring range of this method was 3.00-70.00 ng/mL (7.50-175 nmol/L). Conversion factors are nmol/L×0.40=ng/mL and ng/mL×2.50=nmol/L. Serum calcium, albumin was measured with Roche/Hitachi Cobas c system. The reference ranges and the interpretations of serum 25 (OH) Vitamin D in both mothers and newborns were: (a) Serum 25-OH <20 ng/mL: Vitamin D deficiency; (b) 21-29 ng/mL: Insufficiency, (c) ≥30 ng/mL: Sufficiency [8].

Statistical Analysis

Results were presented as frequencies, percentages for categorical variables, or means with Standard Deviations (SD) for continuous variables for mothers and newborns separately. The alpha error of 0.05 was considered for statistics. Pearson’s correlation coefficient assessed the relation between Vitamin D levels in mothers and their newborns. Chi-square test for association of maternal Vitamin D levels with their sun exposure and newborns birth weight.

Results

The Mean serum 25 (OH) Vitamin D in mothers was 15.09 ng/mL and Mean serum 25 (OH) Vitamin D in neonates was 13.82 ng/mL [Table/Fig-1,2]. The distribution of serum 25 (OH) Vitamin D status in mothers was 75% deficient, 13% insufficient and 12% sufficient. In this study, the religion of 79% of mothers was Hindu, 13% Muslim, 7% Christian and 1% Buddhist. Majority of the subjects being Hindu, the culture of purdah could not explain the high frequency of Vitamin D deficiency. The distribution of serum 25 (OH) Vitamin D levels in newborns was 78% deficient, 13% insufficient and 9% sufficient.

Maternal characteristics and laboratory parameters.

| Variables | n | Mothers |

|---|

| Mean | SDa | Median | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|

| Age (years) | 100 | 31.09 | 4.44 | 31 | 20.00 | 45.00 |

| Weight (kg) | 100 | 74.06 | 10.16 | 74 | 50.90 | 112.90 |

| Height (cm) | 100 | 161.03 | 6.12 | 160 | 150.00 | 174.00 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dL) | 100 | 9.09 | 0.66 | 9 | 6.1 | 11.1 |

| Serum 25 (OH) Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 100 | 15.09 | 6.22 | 13 | 3.00 | 53.84 |

| Serum albumin (mg/dL) | 100 | 3.45 | 0.26 | 3.5 | 2.70 | 3.90 |

a: SD=Standard deviation

Neonatal characteristics and laboratory parameters.

| Variables | n | Newborns |

|---|

| Mean | SDa | Median | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|

| Gestational age (days) | 100 | 263.74 | 9.79 | 262 | 245.00 | 288.00 |

| Weight (kg) | 100 | 2.91 | 0.40 | 3 | 1.82 | 3.76 |

| Length (cm) | 100 | 48.59 | 1.60 | 49 | 45.00 | 53.00 |

| Head circumference (cm) | 100 | 33.36 | 1.21 | 33 | 31.00 | 36.00 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dL) | 100 | 10.18 | 0.99 | 10 | 6.1 | 11.9 |

| Serum 25 (OH) Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 100 | 13.82 | 11.12 | 11 | 3.00 | 48.75 |

| Serum albumin (mg/dL) | 100 | 3.55 | 0.27 | 4 | 2.60 | 4.30 |

a: SD=Standard deviation

Serum calcium was within normal range in 92% women. Hypercalcaemia was noticed in 3% women and hypocalcaemia in 5% women. In neonates, serum calcium was within normal range in 95% and lower in 5% cases.

Serum albumin was normal in 59% of mothers and lower than normal range in 41% of mothers. Almost all i.e., 99% of newborns had low serum albumin levels and 1% had normal serum albumin.

About 87% of mothers had a natural conception, whereas 13% had IVF conception. About 49% of mothers were primigravida, and 51% were multigravida. Primipara mothers were 70% and 30% were multipara. Twenty-six mothers had a prior single abortion; seven mothers had earlier two abortions while two of the mothers had three abortions. Sixty-five mothers had no history of abortion.

Only four mothers (4%) had >4 hours/day of daily sun exposure. Fifty-five mothers (55%) reported less than 2 hours/day of sun exposure and 41 mothers (41%) had 2 to 4 hours/day of sun exposure.

Around 72% of mothers were non-vegetarian, and 28% were vegetarian. Only 5% of mothers received the oral Vitamin D Supplements 3,00,000 IU (5 doses of 60,000 IU soft gels) in addition to that incorporated in calcium supplement formulations.

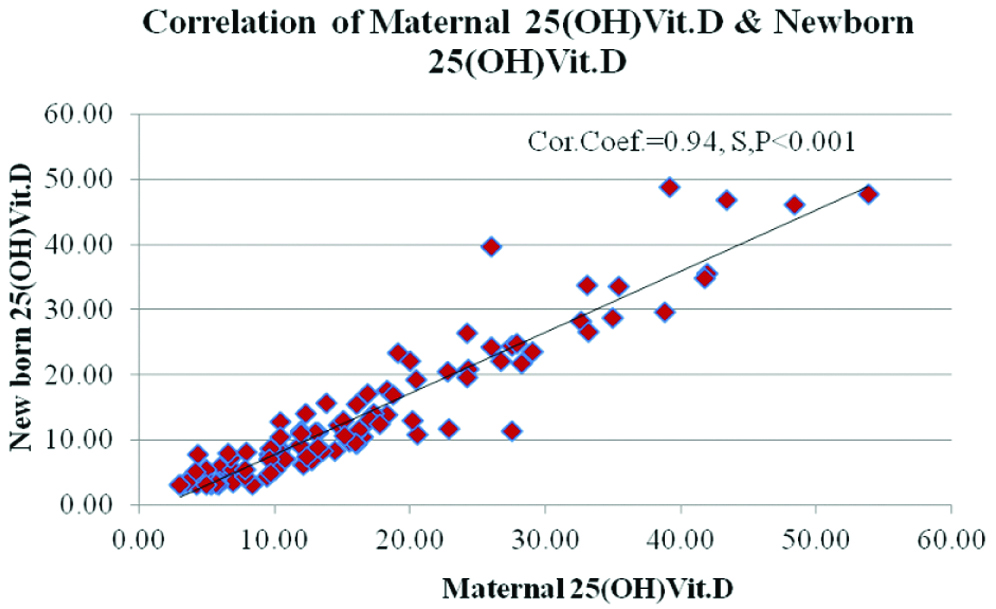

The correlation between maternal and newborns serum 25 (OH) Vitamin D levels with a Pearson correlation coefficient value of 0.94 and the p-value of <0.001 which indicates strong and statistically significant correlation (S) [Table/Fig-3]. The analysis of data reflected the moderate correlation between maternal and newborns serum calcium levels with a Pearson correlation coefficient value of 0.43 and the p-value of <0.001, which shows a statistically significant relationship.

Correlation of maternal serum vitamin D and newborns serum vitamin D levels.

The comparison between serum 25 (OH) Vitamin D levels in mothers and birth weight in newborns found no statistically significant association [Table/Fig-4]. The association between maternal serum 25 (OH) Vitamin D levels and daily hours of sun exposure (up to 2 hours vs >2 hours) was statistically significant [Table/Fig-5]. The five mothers who received 3,00,000 IU Vitamin D supplements were all found to be Vitamin D sufficient. The comparison between serum 25 (OH) Vitamin D levels in mothers and gestational age found no statistically significant association [Table/Fig-6].

Comparison of serum 25 (OH) vitamin D levels in mothers and birth weight in newborns.

| Serum 25 (OH) Vitamin D | Birth weight | Total |

|---|

| Low (<2.5 kg) | Normal (≥2.5 kg) |

|---|

| Sufficient | 1 | 11 | 12 |

| Insufficient | 3 | 10 | 13 |

| Deficient | 17 | 58 | 75 |

| Total | 21 | 79 | 100 |

| Chi-Square test | Chi-statistic | Degrees of freedom | p-value | Association is not significant |

| 1.32 | 2 | 0.517 |

Comparison of daily sun exposure and serum 25 (OH) Vitamin D levels in mothers.

| Serum 25 (OH) Vitamin D | Sun exposure | Total |

|---|

| 0-2 hours/day | >2 hours/day |

|---|

| Sufficient | 3 | 9 | 12 |

| Insufficient | 10 | 3 | 13 |

| Deficient | 42 | 33 | 75 |

| Total | 55 | 45 | 100 |

| Chi-Square test | Chi-statistic | Degrees of freedom | p-value | Association is significant |

| 6.92 | 2 | 0.031 |

Comparison of gestational age and serum 25 (OH) vitamin D levels in mothers.

| Serum 25 (OH) Vitamin D | Gestational age | Total |

|---|

| Late preterm (35-36.6 weeks) | Term (37-41.6 weeks) |

|---|

| Sufficient | 4 | 8 | 12 |

| Insufficient | 3 | 10 | 13 |

| Deficient | 25 | 50 | 75 |

| Total | 32 | 68 | 100 |

| Chi-Square test | Chi-statistic | Degrees of freedom | p-value | Association is not significant |

| 0.547 | 2 | 0.761 |

Discussion

The study results show a very high percentage of pregnant mothers with hypovitaminosis D as well as lower vitamin D levels in newborns. There was a strong, statistically significant relationship between maternal and neonatal vitamin D levels. These findings from a hospital catering to affluent population from the financial capital of India indicate the gravity of the vitamin D problem in the region. We did not find the birth weight to be related to vitamin D levels; however, the study was not powered for the analysis of this parameter. There has been a strengthening of evidence regarding the impact of vitamin D on maternal and foetal outcomes. Hypovitaminosis D in pregnant mothers has been reported to be associated with increased risk of preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, bacterial vaginosis in mothers; and small for gestational age and low birth weight babies [6,7,9,10]. Zheng J et al., study has reported that vitamin D deficiency in mothers can lead to metabolic syndrome in offspring, which may be amenable to the correction of vitamin D deficiency [11]. Maternal vitamin D deficiency adversely affects the musculoskeletal development in the child that can manifest up to early childhood in the form of lower bone mineral content, density and muscle mass. Vitamin D deficiency correction in mother can provide long-term benefit in the prevention of osteoporotic fracture in childhood [12-16]. Thorsteinsdottir F et al., studied Danish case cohorts born between 1992-2002 (D-Tect study). They highlighted the importance of prenatal and neonatal vitamin D status in the healthy immune system and lung development. They suggested that higher vitamin D levels in neonates may reduce the risk of developing asthma at ages 3-9 years in children [17]. Our study results are in line with other Indian studies reporting a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in pregnant mothers and correlation with neonatal vitamin D levels. [Table/Fig-7] highlights the list and findings of similar Indian studies [14,15,18-21].

Indian studies related to Vitamin D deficiency in pregnant mothers [14,15,18-21].

| Author/s and year published | Region | Number of subjects and present study related parameters | Findings |

|---|

| Krishnaveni GV et al., [14], 2011 | Mysore, Karnataka, South India | Serum (25 (OH) D) at 28-32 weeks’ in 568 pregnant women | The median 25 (OH) D was 39.0 nmol/L; of which 379 (67%) mothers had vitamin D deficiency (<50 nmol/L). |

| Marwaha RK et al., [18], 2011 | Delhi | 541 pregnant women of low socio-economic strata recruited for vitamin D evaluation across trimesters and postpartum 6 weeks, serum 25 (OH) vitamin D evaluated in 341 mother infant pairs | Mean serum 25 (OH) D levels was 23.3±12.2 nmol/L. 96.3% vitamin D deficient mothers (vitamin D <50 nmol/L). Strong correlation of vitamin D levels in mother infant pairs (r=0.779, p=0.0001). High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency across trimesters and postpartum. |

| Sachan A et al., [19], 2005 | Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, North India | 207 urban and rural pregnant women, serum 25 (OH) D and serum calcium, serum 25 (OH) vitamin D evaluated in cord blood of 117 newborns | Mean maternal 25 (OH) D: 14±9.3 ng/mL, mean cord blood 25 (OH) D: 8.4±5.7 ng/mL. Vitamin D deficiency (<22.5 ng/mL) was 84.3% in pregnant urban women and 83.6% in rural women. Strong correlation of vitamin D levels in mother infant pairs (r=0.79, p<0.001). |

| Jani R et al., [20], 2014 | Mumbai, Maharashtra, Western India | Serum 25 (OH) D was measured in 150 pregnant women. | All pregnant women 25 (OH) D levels <30.00 ng/mL. Nonaffluent women had lower 25 (OH) D levels than the affluent women (β=-0.20; p=0.03). |

| Farrant HJW et al., [21], 2009 | Mysore, Karnataka, South India | Serum 25 (OH) D at 30 weeks’ gestation in 559 women. The babies’ anthropometry parameters were evaluated. | Median 25 (OH) D: 37.8 nmol/L. Hypovitaminosis D (<20 ng/mL) in 97% women. No association with newborns anthropometry. |

| Sarma D et al., [15], 2018 | Guwahati, Assam, Northeast India | 250 primigravida pregnant women 18-40 years of age in the third trimester and their newborns were evaluated for vitamin D3 levels, association with neonatal skeletal outcomes. | Hypovitaminosis D (<30 ng/mL) in 60% of pregnant mothers and newborns (62.4%). Mean levels were 17.51±2.24 ng/mL and 14.51±1.8 ng/mL among the Hypovitaminosis D mothers and their neonates respectively. Adverse skeletal outcomes in neonates of hypovitaminosis D mothers. |

| Present study | Mumbai, Maharashtra, Western India | Serum 25 (OH) D was measured in 100 pregnant women and their newborns. | Hypovitaminosis D (<30 ng/mL) in 88% of pregnant mothers and 91% newborns. Strong correlation between maternal and neonatal vitamin D levels (0.94, p<0.001). |

With the available research data, hypovitaminosis D appears to be a widespread problem in pregnant mothers and neonates across India. Still, there is a lack of clear guidelines for its management. Endocrine society global guidelines state that pregnant and lactating mothers comprise a high risk group that should be screened for vitamin D deficiency and routinely given vitamin D supplementation [22]. However, American College of Gynaecologists committee on obstetric practice opines that although severe deficiency of vitamin D in mothers is known to be associated with adverse skeletal outcomes in newborns, currently there is not sufficient evidence to recommend screening of all pregnant women for deficiency of vitamin D [23]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines (2016) do not recommend vitamin D supplementation in pregnant mothers for improvement in maternal and neonatal outcomes based on a Cochrane review. WHO recommends advising pregnant women for adequate sunlight exposure and proper nutrition, however, pregnant women with documented vitamin D deficiency are recommended to take supplements of 200 IU, i.e., five micrograms per day [24,25]. Sufficient vitamin D via adequate sun exposure in pregnant women is not feasible in India due to cultural issue of clothing, skin pigmentation, scorching uncomfortable heat, use of sunscreens, atmospheric pollution and overcrowding. Dietary intake of vitamin D is also impacted due to choice of food like vegetarianism, high phytate content of food, high caffeine consumption, cooking practices, and low calcium diet [4,8]. With the lack of guidelines regarding vitamin D screening and supplementation during the antenatal period in India and reports of vitamin D deficiency being a widespread public health concern, there is a need for extensive multicentric studies across the country for proper assessment of the problem and evidence-based recommendations.

Limitation(s)

The study had limitations that serum parathormone was not measured; dietary details are lacking; seasonal variations are not reflected as the study duration was four months. The sample is from a single hospital from Mumbai and generalisation of the findings is not possible.

Conclusion(s)

To conclude, the study results add to the accumulating evidence of a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in pregnant mothers and newborns, which needs further evaluation and response.

Declaration: The financial support for the project was granted by Lilavati Kirtilal Mehta Medical Trust, Lilavati Hospital, A-791, Bandra Reclamation (W), Mumbai-400050.

a: SD=Standard deviation

a: SD=Standard deviation