Pregnancy and childbirth are normal physiological processes with great pathological potentials. Puerperial sepsis, puerperial pyrexia, surgical site infection, chorioamnionitis, endometritis and Postpartum Haemorrhage (PPH) in the mother and neonatal septicaemia, Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS), birth asphyxia, Intrauterine Growth Restriction (IUGR) in the baby are some of the documented adverse outcomes which may occur at any period of gestation [1]. Microbial colonisation of the urogenital tract in the mother is implicated in early onset bacterial infections in the newborn, an ascending but silent amniotic fluid infection, or symptomatic chorioamnionitis. Thus, maternal symptoms may not help identify all infected infants further aggravating the physician’s dilemma. Group B-Streptococcus (GBS) infections are no longer the predominant cause of early onset neonatal sepsis being superseded by gram-negative organisms [2]. In addition, methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus, already a common cause of nosocomial infection in maternity and neonatal units [3], looms as a major cause of early onset neonatal sepsis.

Neonatal sepsis is defined by positive C-Reactive Protein (CRP) readings (CRP >6 milligram per liter (mg/L)). In many studies it was found that the risk of neonatal infection was increased among mothers colonised with GBS. Other risk factors for neonatal infection include premature rupture of membranes >18 hours, maternal fever during labour and prematurity [4-7]. Vaginal microbiome composition changes during pregnancy which includes shift in the vaginal bacteria to a composition that is typically dominated by Lactobacillus [5]. This change is believed to inhibit pathogen growth through secretion of bacteriocins such as lactic acid that maintain an acid pH. Disturbed vaginal environment is associated with complications of pregnancy. Vaginal microbiota isolated from infected amniotic fluid are mostly aerobic bacteria, rather than anaerobe causing bacterial vaginosis. A detailed analysis of the change in vaginal microorganism during pregnancy is critically important to prevent complications that may be associated with it [7-9]. Hence, a HVS culture is a handy tool in the assessment of the vaginal microbiota.

So, this study was done to find out the relationship between the microbiological study of HVS culture with maternal and perinatal complications.

Materials and Methods

This was a hospital-based cross-sectional study which was carried out in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in a hospital at Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India, over a period of six months from July 2019 to January 2020. Two-hundred antenatal women who got admitted in the labour room and fulfilled the following inclusion criteria and gave consent to participate were enrolled for the study and HVS were sent for microbiological analysis. The women whose HVS was sterile were taken as controls (n=112) while the women with non-sterile HVS were taken as cases (n=88). The study protocol was cleared for ethics by research Institutional Review Board (IRB 3733).

Inclusion criteria: Asymptomatic pregnant patients at term gestation. Single live foetus in cephalic presentation.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with features of chorioamnionitis like fever, tachycardia, uterine tenderness or foul smelling liquor. Foetal distress and meconium stained amniotic fluid on admission. Active labour on admission. Patients with history of Antepartum Haemorrhage (APH). Multiple pregnancy, urinary tract infection.

Sample Size Estimation

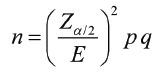

Sample size was based on level of precision; precision consists of significance level and allowable error. In this study, 5% significance and 20% allowable error was considered. Totally, 200 study subjects were included in the study as this number of patients attended hospital during the study period. Finite population correction has been applied to the sample size formula:

Where, Zα/2=1.96, p=prevalence, q=1-prevalence, E-Margin of error for appropriate level of precision (value is 0.05). Confidence interval (CI)=95% Significance=α=5% Sample size ‘n’ comes out to be 177 (i.e., minimum required number of subjects). Then sample size taken for the study was 200.

A detailed history was taken with special attention to antenatal complications and risk factors. A pretested semi-structured questionnaire was prepared to capture all the relevant information. General examination was carried out on all patients falling into the inclusion criteria who gave consent to participate in the study. A per speculum examination was done and condition of vagina and cervix was noted. After insertion of a water-lubricated sterile speculum, a smear was taken from vaginal posterior fornix using a sterile cotton swab. All vaginal culture was incubated primarily under aerobic condition. Classification of patients was done into sterile and non-sterile as per the culture report and outcomes analysed. Maternal outcomes i.e., presence of postpartum complications like PPH, endometritis, puerperial pyrexia, surgical site infection, puerperial sepsis and septic shock were assessed. Delivery outcomes including mode of delivery, birth weight, sex, Apgar score, NICU admission and early neonatal sepsis were investigated. Systematic random sampling was used to enroll the antenatal women in the study.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 11.5. Chi-square test was used for comparison of data for statistical significance. For descriptive statistics percentage, mean and SD was calculated with p value <0.05 considered significant.

Results

Two hundred pregnant women were enrolled in the present study. The number of patients with sterile HVS was 112 and non-sterile HVS was 88. The sterile HVS and the non-sterile HVS groups had comparable age, gravidity and period of gestation. The mean age in the sterile HVS study group was 26.65±2.67 years while that in non-sterile HVS was 26.87±2.61, likewise mean parity was 2.13±0.97 and 2.03±0.81 in the respective groups and mean gestational age was 38.67±1.53 and 38.35±1.12 weeks in sterile HVS and the non-sterile HVS study groups, respectively. Total 64% (56) cases were of class lV socioeconomic status (as per modified BG Prasad classification 2020) in the study group with non-sterile HVS cultures, while the sterile group had only 28.5% (32) participants from low socioeconomic group.

Out of the 88 samples that were non-sterile, E.coli was the most common organism isolated (40.9%) followed by Staphylococcus aureus (29.5%) and Proteus (11.36%) [Table/Fig-1].

Organisms isolated from the HVS.

| Organism | Number | Percent |

|---|

| Sterile | 112 | 56% |

| Streptococcus | 4 | 2% |

| S. aureus | 26 | 13% |

| E.coli | 36 | 18% |

| E.coli with S. aureus | 6 | 3% |

| E.coli with Klebsiella | 5 | 2.5% |

| Proteus | 10 | 5% |

| Klebsiella with Mycoplasma | 1 | 0.5% |

| Total | 200 | 100% |

In the sterile group,62.5% of women and 45.45% of women in the non-sterile group had no maternal complications. PPH (13.39%) was the most commonly reported maternal complication in the sterile group, followed by puerperial pyrexia (8.92%) and sepsis (4.46%). In the non-sterile group, endometriosis (14.77%) followed by sepsis (11.36%) and PPH (11.36%) formed a major part of the reported complications [Table/Fig-2].

Maternal complications in the two study groups.

| Maternal condition | Sterile n=112 | Non-sterile n=88 | Chi-square | p-value |

|---|

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent |

|---|

| Normal | 70 | 62.5% | 40 | 45.45% | 22.224 | 0.002* |

| Sepsis | 05 | 4.46% | 10 | 11.36% |

| Puerperial pyrexia | 10 | 8.92% | 02 | 2.27% |

| Chorioamnionitis | 4 | 3.57% | 05 | 5.68% |

| Wound gaping | 5 | 4.64% | 06 | 6.81% |

| Episiotomy infection | 1 | 00.89% | 02 | 2.27% |

| PPH | 15 | 13.39% | 10 | 11.36% |

| Endometritis | 02 | 1.7% | 13 | 14.77% |

| Total | 112 | 100% | 88 | 100% |

*statistically significant

PPH: Postpartum haemorrhage

In the sterile group, 71.4% patients had vaginal delivery, 24.1% had caesarean section while 1.7% cases had instrumental deliveries. In the non-sterile group, 22.72% cases had caesarean section, 68.18% had normal vaginal delivery whereas 3.4% cases had instrumental delivery. There was no statistically significant between the two groups with respect to mode of delivery (p-value 0.6) [Table/Fig-3].

Mode of delivery in the study groups.

| Mode of delivery | Sterile | Non-sterile | Chi-square | p-value |

|---|

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent |

|---|

| Vaginal | 80 | 71.4% | 60 | 68.18% | 2.252 | 0.689 |

| Instrumental | 02 | 1.7% | 03 | 3.4% |

| Assisted breech | 02 | 1.7% | 02 | 2.27% |

| VBAC | 01 | 0.89% | 03 | 3.4% |

| LSCS | 27 | 24.1% | 20 | 22.72% |

| Total | 112 | 100% | 88 | 100% |

LSCS: Lower segment C-section; VBAC: Vaginal birth after cesarean

Out of 112 deliveries, three (2.67%) still births were reported in the sterile group while there were nine (10.22%) still births in the non-sterile group which was statistically significant. Of all the newborn babies 21.4% in the sterile and 34.09% non-sterile group were males and rest females. Neonatal survival rate and prognosis was better among females. Nearly, 4.46% babies in sterile group and 19.3% among the non-sterile group needed resuscitation in the form of bag and mask ventilation and oxygen via facemask. Among the 112 patients in the sterile group, 12 babies got admitted in the NICU in view of respiratory distress. On the other hand, eight babies in the non-sterile group required NICU admission. APGAR score of the babies at five minute in the sterile group was >7 in 95.53% cases while the same was 79.54% in the non-sterile group. Majority of the babies in both the groups had their birth weight falling between 2.6-3.0 kg. CRP of the babies in the sterile group was more than 6 in 14.2% cases while the same was 31.81% in the non-sterile group, depicting neonatal septicaemia [Table/Fig-4].

Foetal outcome in the two study groups.

| Foetal outcome | Sterile | Non-sterile | Chi-square | p-value |

|---|

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent |

|---|

| Alive | 109 | 97.32% | 79 | 89.77% | 4.979 | 0.0256 |

| Still birth | 03 | 2.67% | 09 | 10.22% |

| Sex of foetus |

| Male | 24 | 21.4% | 30 | 34.09% | 4.009 | 0.045 |

| Female | 88 | 78.5% | 58 | 65.9% |

| Need for neonatal resuscitation |

| No | 05 | 4.46% | 17 | 19.3% | 11.106 | <0.001* |

| Yes | 107 | 95.53% | 71 | 80.68% |

| Need of admission |

| No | 100 | 89.28% | 80 | 90.9% | 0.144 | 0.704 |

| Yes | 12 | 10.71% | 08 | 9.09% |

| APGAR |

| Less than 7 | 5 | 4.46% | 18 | 20.45% | 12.381 | <0.001* |

| More than 7 | 107 | 95.53% | 70 | 79.54% |

| Birth weight |

| 1.5-2 kg | 01 | 0.89% | 02 | 2.27% | 16.753 | 0.002* |

| 2.1-2.5 kg | 01 | 0.89% | 10 | 11.36% |

| 2.6-3.0 kg | 80 | 71.4% | 40 | 45.45% |

| 3.1-3.5 kg | 20 | 17.85% | 25 | 28.4% |

| More than 3.5 kg | 10 | 8.9% | 11 | 12.5% |

| CRP levels (mg/mL) |

| Less than 6 | 96 | 85.7% | 60 | 68.18% | 8.828 | 0.002* |

| More than 6 | 16 | 14.2% | 28 | 31.81% |

*Statistically significant

Both HVS and CRP positive was found in 20% of the total cases (true positive) while 44% had both HVS and CRP negative (true negative) [Table/Fig-5].

Correlation of HVS with CRP levels in the two study groups.

| HVS | CRP | Chi-square value | p-value |

|---|

| Positive | Negative |

|---|

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent |

|---|

| Positive | 40 | 20% | 12 | 6% | 20.374 | <0.001* |

| Negative | 60 | 30% | 88 | 44% |

| Total | 100 | 50% | 100 | 50% |

HVS: High vaginal swab; CRP: C reactive protein; *Statistically significant

In the sterile group 61.6%, while in the non-sterile group 22.7% had no perinatal morbidity. Septicaemia (8.9%) followed by RDS (5.35%) were the most common complications in the sterile group while Meconium Aspiration Syndrome (MAS) (18.18%) followed by RDS (11.36%) and birth asphyxia (11.36%) formed a major part of the complications that were seen to occur in the non-sterile group [Table/Fig-6].

Perinatal morbidities seen in the two study groups.

| Perinatal morbidity | Sterile | Non-sterile | Chi-square | p-value |

|---|

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent |

|---|

| Normal | 69 | 61.6% | 20 | 22.7% | 34.751 | <0.001* |

| Birth asphyxia | 06 | 5.35% | 10 | 11.36% |

| Septicaemia | 10 | 8.9% | 08 | 9.09% |

| Meningitis | 5 | 4.46% | 05 | 5.68% |

| MAS | 5 | 4.46% | 16 | 18.18% |

| NEC | 1 | 0.89% | 02 | 2.27% |

| RDS | 6 | 5.35% | 10 | 11.36% |

| Cord sepsis | 5 | 4.46% | 09 | 10.22% |

| Bronchopneumonia | 5 | 4.46% | 08 | 9.09% |

| Total | 112 | 100% | 88 | 100% |

MAS: Meconium aspiration syndrome; NEC: Necrotising enterocolitis; RDS: Respiratory distress syndrome; *Statistically significant

Discussion

The incidence of non-sterile HVS was high in cases of low socioeconomic status in present study (64%). This can be explained by the fact that poor nutritional status leads to decreased antibacterial activity and increased defects in the foetal membrane. Other factors, which could increase the risk of genitourinary infection include malnutrition, anaemia and poor personal hygiene. In the present study, of the 88 samples that were non-sterile, E.coli was the most common organism isolated (40.9%). Studies done by Gopal AK et al., et al., and Karat C et al., had E.coli as the most common organism isolated from non-sterile swab cultures [10,11]. Son KA et al., also mentioned that E.coli was the most common organism in non-sterile HVS in first trimester and vaginal microbiota becomes successively benign towards term [9]. In the sterile group, 62.5% pregnant women and 45.45% patients in the non-sterile group had no maternal complications. PPH (13.39%) was the most common complication in the sterile group while in the non-sterile group; endometritis (14.77%) formed a major part of the complications. This was in accordance with the studies done by Donati L et al., and Waites KB et al., where endometritis was the most common complication seen in non-sterile cervicovaginal cultures, although their studies had a special mention of infection by mycoplasma or urea plasma microorganisms [12,13].

In the sterile group, 24.1% had caesarean section while 1.7% cases had instrumental deliveries. The indications of operative delivery were prolonged second stage of labour along with poor maternal effort, non-progress of labour or arrest of descent and dilatation and had nothing to do with foetal distress. In the non-sterile group, 22.72% cases had caesarean section and 3.4% cases had instrumental delivery. The difference between the two groups with respect to delivery was statistically not significant (p-value being 0.6). The indications of caesarean delivery were mostly meconium staining of liquor or non-reassuring cardiotocography. This was in agreement with the results found by Vermillion ST et al., Seward PG and McGregor JA and French JI where caesarean delivery was the preferred mode of delivery, even though a trial of normal labour could be given, as it reduced the latency period which would further decrease maternal and perinatal morbidity [14-16]. Though there is a lack of consensus on the best mode of delivery in such cases among the researchers.

Similar to findings in the present study, Son KA et al., reported more still births in the non-sterile group compared with the sterile group, because genitourinary infections cause increase in the incidence of neonatal sepsis and subsequent perinatal morbidity [9]. Of all the neonates, 21.4% in the sterile and 34.09% in non-sterile group were males and the rest were females. Neonatal survival rate and prognosis was seen to be better among females, although no apparent reason for this could be elicited in the study. Study done by Son KA et al., also showed better female survival rate, males being more prone to sepsis inherently [9]. Among the sterile group 4.46% babies and among the non-sterile group 19.3% babies needed resuscitation in the form of bag and mask ventilation and oxygen via facemask for causes like meconium aspiration syndrome, perinatal depression and birth asphyxia. Regarding NICU admissions, the present study showed findings consistent with an earlier report by Aagaard K et al., where more admissions were reported in the non-sterile group [17]. The indication for neonatal admissions being meconium aspiration syndrome, birth asphyxia, respiratory distress and poor APGAR scores at 5 minutes. APGAR scores of the babies at five minute in the sterile group were more than 7 in 95.53% cases while the same was 79.54% in the non-sterile group. Similar outcomes were also suggested by Son KA et al., and Aagaard K et al., in their respective studies, where non-sterile swab cultures had increased incidence of neonatal sepsis, respiratory distess syndrome (pneumonia), meconium aspiration syndrome and low birth weight babies [9,17].

Majority of the babies in both the groups had their birth weight falling between 2.6-3.0 kg which is comparable with the results obtained by Aagaard K et al., in their study [17]. Although some researchers associate non-sterile HVS cultures with low birth weight babies due to poor maternal nutrition and genitourinary infections leading to Premature Prelabour Rupture Of Membranes (PPROM) and prematurity, which was not the case in present study. CRP of the babies in the sterile group was more than six in 14.2% cases while the same was 31.81% in the non-sterile group, depicting neonatal septicaemia. A 20% of the total cases had both HVS and CRP positive (true positives) while 44% had both HVS and CRP negative (true negatives). This finding was in agreement with a hospital based study of patients by Gopal AK et al., [10]. Mothers with positive vaginal culture for GBS gave birth to babies who were characterised with significant sepsis symptom, including poor feeding, lethargy, hypo/hyperthermia, poor muscle tone, and irritability as also reported by Kayiga H et al., Shirazi M et al., and Krohn MA et al., [18-20]. In the sterile group 61.6%, while in the non-sterile group 22.7% had no perinatal morbidity. Septicaemia (8.9%) followed by RDS (5.35%) were the most common complications in the sterile group while, MAS (18.18%) followed by RDS (11.36%) and birth asphyxia (11.36%) formed a major part of the complications that were seen to occur in the non-sterile group, which was in accordance to the studies done by Donati L et al., Waites KB et al., Shirazi M et al., Krohn MA et al., and Sgro M et al., [12,13,19-21], respectively. All these researches associated foetal complications with PPROM, prematurity low birth weight and neonatal septicaemia, which to some extent were the complicating factors in present study.

Limitation(s)

The study did not focus on patients with high risk conditions such as hypertension, gestational diabetes mellitus, preterm cases, etc. Thus, a detailed study with broader inclusion criteria should have been undertaken for validating the results so obtained. As, it was a hospital based study Berkesonian bias cannot be ruled out.

Conclusion(s)

Abnormality in vaginal microbiota leads to adverse maternal and foetal outcomes, understanding vaginal microbiome may thus be the first step to introduce a preventive strategy for improving maternal and foetal complications.

*statistically significant

PPH: Postpartum haemorrhage

LSCS: Lower segment C-section; VBAC: Vaginal birth after cesarean

*Statistically significant

HVS: High vaginal swab; CRP: C reactive protein; *Statistically significant

MAS: Meconium aspiration syndrome; NEC: Necrotising enterocolitis; RDS: Respiratory distress syndrome; *Statistically significant