Marriage has a life-altering effect on people. It usually occurs at a younger age but some individuals may postpone or even avoid getting married, until the end of their life. There might be several reasons for staying single until later in life. Some factors like psychological and social autonomy, self-sufficiency, financial possibilities can influence the decision for marriage [1,2]. The theory of social clocks by Neugarton BL emphasises that postponement of any important task such as marriage and parenting might be considered abnormal and criticised by society and these conditions could have a negative impact on the person [3,4]. The sixth and seventh stages of Erikson theory indicate that people seek love and intimacy between the age of 19 to 40 and they need to have generativity usually by having children between the ages of 40 to 65. Lack of success in these normal stages can result in isolation and despair which shallow involvement in the society in later life [5].

It is estimated that between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the global population over 60 years will approximately double from 12% to over 21%. By 2050, the world’s population aged 60 or over is projected to reach two billion, up from 900 million in 2015. Nearly 80% of these individuals will live in low and middle income countries [6]. The rise in the age of marriage suggests that in the near future, the number of never married older adults will increase, too. At the beginning of 21th century, 7.2% of older men in Taiwan and 7.0% of older women in Philippines were never married [7]. It is estimated that in some countries such as South Africa, Singapore and Brazil between 9% to 16% of men and over 10% of women aged 65 and older are ‘never married’ after 2025 [7]. It has been reported that never married older adults have a higher risk of developing frailty [8,9]. A large proportion of this group live alone [10]. Older adults who live alone are 50% more likely to be admitted by emergency rooms and 40% more likely to be visited more than 12 times a year by a general physician [11]. This can be more challenging for never married older adults who live in developing countries without adequate formal health care services.

During the last decades, many researchers have focused on the characteristics of the never married older adult. Some of these researchers believe that the above mentioned individuals can be categorised as a separate group in the society while other researchers deny the major differences [12,13]. Given that both ageing and singlehood can influence different dimensions of life, and the fact that most studies have focused on specific topics, a holistic approach seems necessary in order to make this phenomenon more understandable. This study aimed to compare and interpret the results of previously conducted studies on the characteristics of never married older adults and to develop a more comprehensible categorisation of the results.

Materials and Methods

This study has used an integrative review method recommended by Whittemore R and Knafl K to explore the characteristics of the target group. It consisted of five stages: problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, interpretation and presentation of results (discussion and conclusion) [14]. This method allows researchers to collect, evaluate and analyse a variety of quantitative and qualitative data [15].

Data collection and analysis lasted from February 2019 to August 2019. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Registration number: IR.USWR.REC.1398.014).

Literature Search and Data Collection

The inclusion criteria were all qualitative and quantitative published English papers in “PubMed, ProQuest, Web of Science and Scopus” databases (published between 1973 and 2019), with the words “never married” and “elderly” or “older” or “seniors” “in their titles or abstracts,”. The search process was completed by reviewing the cited references.

Data Evaluation

Exclusion criteria to evaluate papers and to extract the usable results, included:

Studies focusing on the never married adult younger than 60 (aged 20 to 59).

Studies without differentiation between unmarried groups (never married, widowed, divorced)

Census reports

Studies on specific diseases or medical conditions.

Macro level studies such as policy making, health economics

Studies on institutionalised older individuals

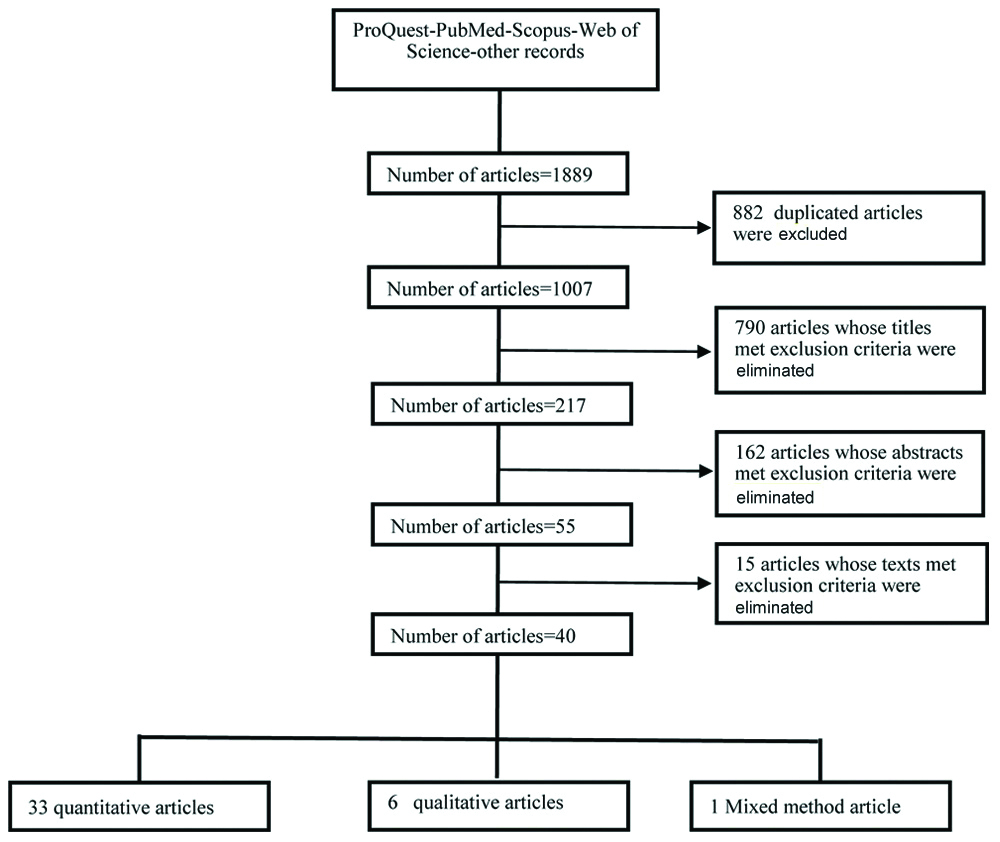

As shown in [Table/Fig-1], 1889 articles were initially found. Finally, 55 full text articles were reviewed and 40 articles (published between 1975 to 2019) were selected for the final analysis.

Flowchart of article selection.

Results

In the present study, the findings obtained from 40 quantitative, qualitative and mixed method studies have been coded and categorised to construct sub-categories and main categories by an integrative method. This can make the results more comparable and understandable. [Table/Fig-2,3] indicate that most studies were quantitative and were conducted in developed countries [8-10,12,16-50]. [Table/Fig-4,5 and 6] show the categorisation of the findings.

Characteristics of included quantitative studies [8-10,16-44]. ELSA: English longitudinal study of ageing; HRS: Hepato renal syndrome

| Author(s) Year | Country | Journal | Method | Sample Size | Male-Female | Aim of study |

|---|

| Ward RA 1979 [16] | US | Journal of Gerontology | Comparisons were drawn between the never married and ever married by Multiple Classification Analysis (MCA) | 9,120 in total | Not mentioned | The characteristics of the never married |

| Fengler AP et al., 1982 [17] | US | International Journal of Sociology of the Family | A range of conditions including life-satisfaction were examined in a cross-sectional study | 1,400 usable interviews | Male-39%Female-61% | Life-satisfaction |

| Taylor RC and Ford EG 1983 [18] | US | Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners | A cross sectional study on 11 risk groups | 619 individuals | Male-19.7%Female-80.3% | The nature of risk for older adults |

| Lawton MP et al., 1984 [13] | US | Research on Aging | Data from three samples of older adults were analysed in terms of relationship between marital status and household structure | - National Senior Citizens Survey: 3996 people- Harris Survey: 2797 people- Local random sampling: 1269 people | Not mentioned | Living arrangement and well-being |

| Kramer M et al., 1985 [19] | US | Journal of the American Geriatrics Society | A cross sectional study on the health and mental healthof an ambulatory population. | 3481 respondents | Male-1,322Female-2,159 | Mental disorders |

| Stull DE and Scarisbrick-Hauser A 1989 [20] | US | Research on Aging | Multiple regressions was employed for data analysis of the 1979 wave of Longitudinal Retirement History Study | 7352 respondents-4350 for analysis | Not mentioned | Life situation |

| Lee GR and Shehan CL 1989 [21] | US | Research on Ageing | Regression analysis on self-esteem | 3004 respondents | Male-1,395Female-1,609 | Social relations and self-esteem |

| Goldman N et al., 1995 [22] | US | Social Science and Medicine | A series of logistic models were used for data analysis of the Longitudinal Study of Aging | 7478 persons | Male-2847Female-4631 | Health |

| Wenger GC et al., 1996 [10] | UK | Ageing and Society | A statistical modelling technique was used to refine models of isolation and loneliness | 534 persons | Not mentioned | Social isolation and loneliness |

| Wolf DA et al., 2002 [23] | US | Journal of Women Aging | Using data from the 1984-1990 Longitudinal Study of Aging, transitions among functional statuses were studied | 7,527 individuals | Female-7,527 | Active life |

| Pinquart M 2003 [24] | Germany | Journal of Social and Personal Relationships | Predictors of loneliness were investigated using data from the study of ‘Lebensführung älterer Menschen’ | 4,130 individuals | Male-40%Female-60% | Loneliness |

| Kaplan RM and Kronick RG 2006 [25] | US | Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health | Logistic regression was employed for comparing likelihood of death, using data from the 1989 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) merged with the 1997 US national death index. | 80,018 cases | Male-52%Female-48% | Longevity |

| Trollor JN 2007 et al., [26] | Australia | Acta Neuropsychiatrica | The prevalence of ICD-10 and DSM-IV disorders was estimated in a sample of older Australian residents | 1,792 respondents | Male-731Female-1,061 | Mental disorders |

| Cwikel J et al., 2006 [27] | Australia | Social Science and Medicine | A cross-sectional descriptive study using data from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health” | 10,108 individuals | Female-10,108 | Health and socialcircumstances |

| Manzoli L et al., 2007 [28] | Italy | Social Science and Medicine | Systematic review and meta-analysis by pooling 53 independent comparisons | More than 250,000 older subjects | Male-42.8%Female-57.2% | Mortality |

| Ahangari M et al., 2007 [29] | Iran | Journal of Ageing-Salmand | A cross-sectional descriptive-analytical study | 300 participants | Male-223Female-77 | Quality of life |

| Karlamangla AS et al., 2009 [30] | US | American Journal of Epidemiology | Mixed-effects modeling of data from a national sample to determine demographic and socioeconomic predictors of trajectories of cognitive function | 6,476 individuals | Male-38.7%Female-61.3% | Cognitive function |

| Grundy EM and Tomassini C 2010 [31] | England and Wales | Public Health | Poisson logistic regression on data from the Office for National Statistics Longitudinal Study | 75,040 individuals | Male-33,700Female-41,340 | Health and mortality |

| Petersen RC et al., 2010 [32] | US | Neurology | A prevalence study was conducted during the baseline contact to establish a cohort for longitudinal study | 1,969 subjects | Male-1,002Female-967 | Mild cognitive impairment |

| Rendall MS et al., 2011 [33] | US | Demography | Logistic regression was used to estimate discrete-time hazard models of the probability of death in the next year. | 582,211 person year | Male-269,986 person yearsFemale-312,225 person years | Marriage and survival |

| Berntsen KN 2011 [34] | Norway | Berntsen BMC Public Health | Discrete-time hazard regression | 11 102 306 person-years of follow-up | Male-4 335 845 person-yearsFemale-6 766 461 person-years | Mortality |

| Koc Z 2012 [35] | Turkey | Journal of Clinical Nursing | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 348 participants | Male-40.6%Female-59.4% | Loneliness |

| Windsor TD et al., 2012 [36] | Australia | The Journals of Gerontology, Series B | A cross-sectional study and regression analysis for investigating predictors of family, neighbour, and friend network size | 552 individuals | Male-268Female-284 | Social relations |

| Liu H and Zhang ZM 2013 [37] | US | Population Research and Policy Review | Data from the National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS) 1997-2010 were examined by logistic regression model | 170,446 observations in final analysis | Male-147,149Female-23,297 | Disability |

| Brenowitz WD et al., 2014 [38] | US | Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders | Multivariable Cox proportional hazard models were used | 5,335 participants | Male-1,755Female-3,580 | Mild cognitive impairment |

| Graham M 2015 [39] | Australia | Women’s Health Issues | Longitudinal linear mixed models with time varying variables were used for analysing 10 waves of data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia | 52,381 total sample size | Female-52,381 | Health and well-being |

| Musić Milanović S et al., 2015 [40] | Croatia | Psychiatria Danubina | A cross-sectional study using self-rating scales | 769 participants | Male-449Female-320 | Depression and associated socioeconomic factors |

| Trevisan C et al., 2016 [9] | Italy | Journal of Women’s Health | Multivariate logistic regression models were used for data analysis of a cohort study | 1,887 subjects | Male-733Female-1,154 | Frailty |

| Secil GG and Nesrin N 2016 [41] | Turkey | International Journal of Medical Research and Health Sciences | A descriptive and co-rrelational study | 343 participants | Male-160Female-183 | Falls and disability |

| Williams L et al., 2017 [42] | China | Population Health | Using longitudinal data from the 2010 and 2012 waves of the China Family Panel Studies, the effects of marital status on physical and mental health were investigated | 9,831 respondents | Male-4,989Female-4,842 | Physical and mental health |

| Lin IF et al., 2017 [43] | US | Research on Aging | Descriptive statistic and logistic regression were employed to predict the likelihood of being poor across marital biographies using the data of HRS | 9,649 individuals total | Male-4,548Female-5,101 | Social security and poverty |

| Thompson MQ et al., 2018 [8] | Australia | Australasian Journal on Ageing | Frailty was measured in a combined cohort of 8,804 Australian older adults | 8,804 participants | Male-14%Female-86% | Frailty |

| Wood N et al., 2019 [44] | England and US | PLoS ONE | Multiple linear regression was carried out on Wave 4 (2008) of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) and Waves 8 and 9 (2006 and 2008) of the US Health and Retirement Study (HRS) | ELSA7520HRS13103 | Male-ELSA3,391HRS5,512Female-ELSA4,129HRS7,591 | Physical capability |

Characteristics of included qualitative and mixed method studies [12,45-50].

| Author (s) Year | Country | Journal | Method | Sample size | Male-female | Aim of study |

|---|

| Gubrium JF 1975 [12] | US | The International Journal of Aging and Human Development | Interview | 22 singleOlder people | Not mentioned | Quality of single life in old age |

| Rubinstein RL 1987 [45] | US | The Gerontologist | Qualitative: Biographic and ethnographic interviewQuantitative: A cross-sectional descriptive study | Qualitative: 47Quantitative: 232 | Male-Qualitative: 47Male-Quantitative: 111Female-Quantitative: 121 | To reconsider earlier views |

| Obrien M 1991 [46] | Canada | Social Indicators Research | A qualitative approach and interview | 15 never married participants | Female-15 | The life experiences |

| Rubinstein RL et al., 1991 [47] | US | Journals of Gerontology | Analysis of qualitative, ethnographically based interviews | 31 never married older women | Female-31 | Key relationships |

| Paradise SA 1993 [48] | USJamaica | Women and Therapy | Interview | 6 persons from US and Jamaica | Female-6 | To examine the life theme and coping skills |

| Timonen V and Doyle M 2014 [49] | Ireland | Ageing and Society | A qualitative narrative approach | 26 participants | Male-12Female-14 | To explore the interpretations and meanings that older adults attach to singlehood |

| Band-Winterstein T and Manchik-Rimon C 2014 [50] | Israel | The International Journal of Aging and Human Development | A qualitative-phenomenological approach and semi-structured interviews | 16 participants | Male-8Female-8 | The experience of being never married |

| Summative results in the extracted papers | Codes | Sub-categories | Category |

|---|

| Married and never married groups did not differ in interaction with neighbors [20] | Interactions such as others | Similar socioeconomic life | As well as others |

| Married and never married groups were not different in participation in organisational activities and meeting club [20] | Same social activity and participation |

| No significant difference in education of never married older men compared to other groups [16] | Same education level |

| The never married are no more likely to be isolated than the married and they have friends nearby and feel a part of the society [17] | No higher level of isolation |

| The data did not indicate that never married older people uniformly live in lifelong or present day isolation [45] |

| Compared to older married individuals, they are socially active and they are not isolated and at high risk of institutionalisation [20] |

| They did not have a significant decline in their household amenities [18]. | Same material living conditions |

| No difference was reported about self-esteem of men in the never married and married groups [21] | No difference in personality | Same psychological situation |

| They reported the same self-confidence compared to the rest of population [18] |

| Their psychological well-being evidenced any relative deficit among the never married [13] |

| Their cognition conditions was not different than those of other marital status [13] |

| There was no significant difference in risk of MCI for participants who were never married at baseline compared to the married participants [38] |

| There was no significant higher anxiety in never married older adults [18] |

| They did not report significantly more loneliness [18] | Same level of loneliness |

| They do not necessarily feel lonely [12] |

| Severe loneliness was not reported by never married men interviewed in the qualitative study [45] |

| There was not enough evidence in the qualitative studies indicating that the never married older adult’s sense of loss and bereavement is different from that of the married [45] | No difference in the sense of loss |

| Their life-satisfaction and happiness were not significantly different from the rest of population [18] | Same happiness and satisfaction |

| They are not different from married older people in life-satisfaction [17] |

| Although they have lower income, they do not perceive that their income is inadequate [17] |

| The health of the never married is not worse than that of other marital groups [20] | Similar general health | Having the same physical health condition |

| Their health condition was not different from those of other marital status [13] |

| They have similar self-rated health compared to married older adults [18] |

| They did not significantly report more recent symptoms [18] |

| They did not have significantly more chronic conditions [18] |

| They did not report extended period of illness or perceive themselves as having poorer health [17] |

| There was no significant association with long term illnesses in the never married older women in 1991 [31] |

| Men in the 65+ age category were not significantly at greater risk of early death if never married [25] | Not higher mortality risk |

| They are not significantly different in function and activity [18] | Same physical activity and function |

| Older adults falls and fall risk factors at home did not differ significantly between never married and married [41] | No difference in the risk of frailty and fall |

| Frailty was not significantly higher in older men who were never married [8] |

| Summative results in the extracted papers | Codes | Sub-categories | Category |

|---|

| The never married reported larger neighbor networks relative to those who were partnered [36] | Strong social and family relations | Social advantages | “Singleness as a premium” |

| All women who had participated in the study were connected to their family and managed to coordinate life and career decisions with family needs [48] |

| They enjoy strong family ties and networks [50] |

| There is clear evidence of having significantly more friends [18] |

| Never married older women had strong family ties and sense of obligation [46] |

| Friends were very significant in the lives of never married older women [47] |

| Never married older women joined in with a community of friends and this progressed through in later life [48] | Community involvement |

| Never married women were the most socially active among females [22] |

| They have more community involvement [16] |

| Older never married women are more active as members of social groups than other older women [27] |

| They had a higher education than married individuals [17] | More educated |

| Never married childless women had significantly higher levels of education [27] |

| Women with higher education were more likely to remain single until old age [16] |

| Never married older adults who had chosen singlehood associated this status with independence, self-fulfillment and autonomy [49] | Autonomy |

| Never married older women had a strong sense of independence [46] |

| They were realistic about ageing and expressed few regrets about the past [46] | Positive personality characters | Better psychological Situation |

| Never married older women are rational [46] |

| Never married older women are positive and relied on their inner strength and determination [46] |

| Never having been married were associated with less likelihood of having symptoms of an affective disorder [26] | Better mental health |

| They do not experience bereavement following spouse death [12] | Lower sense of loss |

| All women who had participated reported high levels of satisfaction in their life [48] | Being happy and satisfied |

| They had higher life-satisfaction than other marital groups [20] |

| Most of them were satisfied with their houses [17] |

| Women were satisfied with their lives, relations with their family members and friends [46] |

| Women participants had no regrets about being never married [48] |

| Never married childless women enjoyed better health and well-being [39] | Higher general health | Higher level of physical health |

| Never married women have about two-thirds the odds of married women of being disabled at follow-up [22] |

| The never married older participant had a higher general health compared to other marital status [29] |

| The never married older women had lower odds of reporting long term illnesses [31] |

| Never married white women with high education lived longer and healthier [23] | Longer life span in women |

| All never married older women reported high levels of function [48] | Better physical activity and function |

| Married women’s earnings were higher than those who were unmarried [33] | Adequate income | More adequate employment |

| Almost all women who participated in the study had adequate income [46] |

| Single women, had the highest income among all with any marital status, although the differences were not statistically significant [16] |

| They are significantly better off in terms of income [18] |

| They are more attached to work and retirement is more problematic for them [16] | Proper occupation |

| All women who participated in the study used to work outside the home during their adult lives [48] |

| The women who participated in the study, had suitable jobs [46] |

Category 3: Downsides [8-10,12,13,16-22,24,25,28,30-37,40,42-45,49,50].

| Summative results in the extracted papers | Codes | Sub-categories | Category |

|---|

| Never married older adults have lower frequency and quality in family ties [16] | Lower social and family relations | Social disadvantages | Downsides |

| They had lower interaction with family and friends [13] |

| They were less likely to have relations with relatives than married respondents [20] |

| They have fewer confidants and fewer family members living nearby than the rest of older adults [18] |

| They are reported as less likely to receive care in a crisis [17] |

| The never married reported smaller family networks [36] |

| Never married participants appeared to be more likely to be isolated [10] | Isolation |

| The never married older adult were more likely to live alone [16] |

| They are more likely to live alone [17] |

| They are relatively isolated in old age [12] |

| Never married older women had slightly lower self-esteem than married women [21] | Negative personality characters | Psychological problems |

| Never married participants had larger practice effects and faster declines than married participants [30] | Mental health deterioration |

| The prevalence of MCI was higher in men who were never married [32] |

| Rates of cognitive impairment increase markedly with age andhigh rates of this disorder were found among those never married [19] |

| Never married older adults had higher depression scores than those who were married [42] |

| Prevalence of depression is higher in never married older adults [40] |

| Loneliness is significantly higher in never married older people [35] | Loneliness |

| Never married adults reported higher levels of loneliness [24] |

| The data indicated loneliness was a problem for some never married older individuals in the quantitative part of the study [45] |

| They experience feelings between loneliness, aloneness and solitude [50] |

| The never married are disadvantaged relative to the married in later life with regard to happiness and excitement [16] | Dissatisfaction |

| Never married older adults who had been constrained in their choice of marital status felt regret and dissatisfaction with their single status [49] |

| The never married reported lower levels of life-satisfaction [42] |

| Married persons were slightly more likely to report their health as good or excellent than the never married [16] | Lower levels of general health and physical capability | Susceptibility to physical health disorders |

| It was found that never married men and women had poorer physical capabilities than their married counterparts [44] |

| The results indicated that marriage is a protective factor for people in older age [33] |

| Those who had never been married reported lower physical health than those who were married [42] |

| They have higher ADL and IADL disabilities than the married [37] |

| Compared to married individuals, the never married had slightly significant higher RR of death [28] | Higher risk of mortality |

| Relative to married persons, those who are never married have significantly higher mortality for most causes of death [34] |

| Never married 65+ women were at greater mortality risk [25] |

| Relative to married older men, the never married had raised mortality in 1991-2001[31] |

| Frailty was significantly higher among women who were never married [8] | Vulnerable to frailty and fall |

| Men who had never married had a higher risk of developing frailty [9] |

| Married men earnings exceeded those who were unmarried [33] | Lower income | Economic insufficiency |

| Married males earned significantly more than those who were not [16] |

| The never married are considerably more likely to have lower income [17] |

| Never married men have lower financial status [22] |

| Gray divorced and never married women face considerable economic insecurity [43] |

| The data showed objective residential quality is poorer in the never married [13] | Material properties |

| They were less likely to own a house [17] |

MCI: Mild cognitive impairement, ADL: Activities of daily living, IADL: Instrumental activities of daily living, RR: Relative risk

Three main categories emerging from the findings included “as well as others”, “singleness as a premium” and “downsides”.

As Well As Others

This main category refers to those findings that indicate there is no or little difference between never married older adults compared to other marital status groups in the subject of the study. This theme has three subcategories: “similar socioeconomic life”, “same psychological situation” and “having the same physical condition”. These findings indicate that never married older adults have the same relations with their family and generally they are not more isolated [17,20,45]. They participate in social activities like other marital groups and they benefit from the same level of education [16,20]. Their personality, self-confidence, self-esteem and cognition abilities do not differ from other older adults, and they do not experience more loneliness or anxiety. In their later life, they have the same feelings of happiness, satisfaction and sense of loss compared to other older adults [13,18,21,38,45]. They have also reported the same levels of physical health and function [8,13,17,18,20,25,41]. Based on these studies, economic evaluations have revealed no decline in the material properties of never married older adults compared to their peer groups [18].

Singleness as a Premium

Premium refers to those findings which indicate better, or healthier conditions in married older adults compared to other marital status groups. It includes four subcategories of “social advantages”, “better psychological situation”, “higher level of physical health”, and “more adequate employment”. These findings suggest that never married older adults have larger social networks and closer connections with family and friends. They enjoy strong family relations and have more friends [36,46,48]. They are more active compared to other individuals at the same age and they have a higher level of education which is more significant for women. They are more independent than other older adults [27,48,49]. These findings have shown that they are realistic and rational people with few regrets about their past and enjoy better mental health and a lower sense of loss. They are satisfied with their lives and their connections with others [12,17,20,26,46]. They also have better general health and longer life spans which are dominantly reported in women. The never married older participants in these studies have reported higher levels of function and less disabilities [22,29,31,39,48]. The results of several studies clustered in this category have shown higher incomes and good occupations particularly in never married older women [16,18,46].

Downsides

In contrast, the “downsides” concept refers to the findings which imply worse conditions in the never married older group. These findings have been classified in four sub-categories: “social disadvantages”, “psychological problems”, “susceptibility to physical health disorders”, “economic insufficiency”. These findings indicate that never married older adults have lower frequency and quality in their family ties and social networks and are more likely to be alone and isolated [10,12,13,17,18]. They have shown more decline in cognition and mental health with higher depression rates than those in married groups. Furthermore, they feel lonely more frequently and regret their marital status. They have also reported less happiness and life-satisfaction [16,24,30,32,35,40,42,49]. These studies also indicate that the physical capability of the never married older adult is lower than that of a married older adult. They are also at a greater risk of frailty and mortality [9,25,28,33,34,42,44]. Some studies have reported less income and lower residential quality in the never married older adults particularly in men. Moreover, they were less likely to own a house [13,17,22,33].

Discussion

An overview of the extracted articles shows that most of these articles are quantitative and conducted in more developed countries. The findings were clustered into three main categories: “as well as others”, “singleness as a premium” and “downsides”. Although in many areas the results are different and sometimes contradictory, it is possible to bridge between the different concepts or find the knowledge gaps.

In the social area, some papers indicated that the never married older adult are more likely to live alone and have less kin relations [16-18]. On the other hand, there are several studies indicating that these individuals are socially active and benefit from a larger networks of friends and neighbours. This community involvement which is more significant amongst women, can play a compensatory role to avoid loneliness. Contacts with friends and voluntary association participation have also been reported as important predictors of happiness in never married older adults [36,46,48].

Most of studies investigating the education and the occupational history of the never married older women, indicated that they had higher levels of education and income than their married counterparts. These associations cannot solidly present a causative explanation, but theoretically, people who are attached to their education and work are more likely to stay single [51]. On the other hand, Ward RA emphasises that education is more critical for the never married to achieve a successful life. Single women have to put more energy and resources into education and work to overcome financial obstacles, because they are not supported by a husband [16]. There might also be a social stigma against employed women in some cultures which can hinder their marriage too. Unlike women, never married older men have reported less income in comparison with married groups. There might be some explanations for that. It is indicated that lacking income is a reason for staying single. From a life course perspective, if this insufficiency continues, the person is less likely to be married in later life [2].

In the physical and mental health area, there is not enough consistency in the results. Many researchers have focused on mortality among the marital groups. Manzoli L et al., who studied mortality in different marital groups by systematic review and meta-analysis reported a RR of 1.1 for the never married groups which showed no large differences [28]. Rendal MS et al., who studied 20.000 to 40.000 households between 1984 and 1986 showed that marriage plays a protective role against mortality. This protection effect is more dominant in men [33]. Risky behaviours in single men might be one reason for the advantage of marriage for them. On the contrary, more recent studies in health issues have reported better health conditions among never married older adults [39,52]. However, it seems that these results should be interpreted with caution. Most of the studies on the health status of the older adults are conducted on community-dwelling older adults [28]. As never married older adults with illnesses or disabilities have less informal support compared to their married counterparts, they are more likely to be institutionalised. Therefore, those who remain in the society are relatively healthy [23].

One factor which can considerably decrease the external validity of the results is cultural differences. These differences can be observed in cross-cultural studies. For example Paradise SA reported differences between American and Jamaican women in their reasons for singleness and their job satisfaction [48]. Fengler AP et al., have reported different levels of life-satisfaction in rural and urban areas of Northwestern Vermont [17].

Some of the inconsistencies in the results might originate in the cohort effect which has also been described in some studies. Timonen V and Doyle M have paid attention to this effect as a central role. In their study, the oldest participants had experienced the starkest socioeconomic and cultural constraints which could influence their marital status [49]. On the other hand, never married participants might have casual partners and cohabitation is on the increase in some societies too [53]. These conditions can narrow the differences between the never married and married older adults. However, human development is a lifelong process, and the pathways influencing the life course are greatly dependent on historical and geographic contexts [54].

Limitation(s)

Some researchers might present results contributed by the life status of the never married older without having any related word in the title and abstract. These articles might not have appeared in the extracted results which majorly had focused on the related key words in titles and abstracts.

Conclusion(s)

Although the never married older adult can have specific premiums (e.g., higher education and income in women) and also disadvantages (e.g., more social isolation) no single model can be presented for the life and character of them. It seems the phenomenon is largely multifactorial and culture-based and that it depends on “time, place and relations”. Most of the studies are quantitative and have been conducted in developed countries. This may not necessarily reflect the characteristics of never married older adults in developing countries. There are still many controversial and unknown perspectives which should be explored in further researches using different methods including qualitative ones. The health issues of the never married older and their access to formal health and social care services need to be investigated in developing countries as well.

MCI: Mild cognitive impairement, ADL: Activities of daily living, IADL: Instrumental activities of daily living, RR: Relative risk