An important cause of acute undifferentiated fever is Scrub typhus caused by a bacteria called Orientia tsutsugamushi, belonging to the family Rickettsiaceae. It is an obligate intracellular parasite of mites. It is naturally maintained in the mites by transmission from female to its eggs (transovarial transmission) and from eggs to larva and then to adults (transstadial transmission). Trombiculid mites lay eggs in areas of heavy scrub vegetation, especially during the rainy season. Humans get infected by the bite of an infected larval mite (chigger) [1,2].

Scrub typhus is an endemic and re-emerging disease in the South-East Asia, Northern Australia and Islands of Pacific and Indian Ocean [3,4]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has rated scrub typhus as one of the most under-diagnosed illnesses that require hospitalisation [5]. In Asia, about 1 million new cases are identified annually [6]. The WHO emphasised the need for better understanding of the outbreaks and pathogenesis associated with this potentially fatal illness [5]. New emerging cases across the globe are challenging the classical epidemiology of Scrub typhus.

There is a higher risk of infection in agricultural labourers in the endemic region [7]. Historically, rice farming was associated with scrub typhus infection whereas studies from Taiwan found dry farming as risk factor [8]. In a study from North-East India, exposure to domestic animals has been associated with increased risk of infection [9].

After an incubation period of 6-21 days, the onset of illness is characterised by fever with chills, headache, myalgia, maculopapular rash, regional lymphadenopathy, characteristic eschar (at the site of bite) and mental changes ranging from confusion to coma [10]. Complications of scrub typhus infection include pneumonia, ARDS [11,12], myocarditis [13], encephalitis, hepatitis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, haemophagocytic syndrome [14], acute kidney injury [15], acute pancreatitis [16], transient adrenal insufficiency [17] and subacute painful thyroiditis [18]. Scrub Typhus also causes neurological involvement such as meningitis, meningoencephalitis or encephalitis [19]. Patients with severe illness develop multi-organ dysfunctions leading to death. ARDS is one of the serious complications of Scrub typhus. In untreated patients, the mortality of scrub typhus ranges from 0-30%, which varies with age and the region of infection [11,12]. Serological assays (indirect fluorescent antibody and enzyme immuno-assay) are the mainstays of laboratory diagnosis of Scrub Typhus.

The authors conducted this retrospective study in order to observe the patient profile, clinical manifestations and complications associated with Scrub Typhus. To the author’s knowledge, this study is one of the largest study from Odisha, a South-Eastern state of India. It shall also prove beneficial for clinicians to better understand the systemic involvement and complications of this re-emerging disease and empower them in early diagnosis and institution of therapy.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

It was a cohort study in which the data was retrospectively collected from the Medical Record Department (MRD) of Kalinga Institute of Medical Sciences (KIMS), Bhubaneswar, India. The authors reviewed the clinical, laboratory, treatment and outcome data of 240 patients who were admitted in Department of Internal Medicine. These patients were admitted between January 2016 and December 2018 and were diagnosed with Scrub Typhus.

Inclusion criteria: The patients included in the study were >18 years of age and positive for Scrub Typhus IgM antibodies by ELISA method.

Exclusion criteria: Patients who had acute coronary syndrome in the last three months, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, known malignancies or immunodeficiency states were excluded from the study.

The cases for the study were selected in accordance with the above-mentioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. The authors obtained detailed demographic, clinical, haematological and biochemical data. The patients underwent testing for specific IgM antibodies against O. tsutsugamushi using a commercial ELISA kit (InBios International Inc. USA). The kit uses O. tsutsugamushi derived recombinant antigen mix. The test was performed as per manufacturer’s instructions. Treatment outcomes were noted for each patient included in the study. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee vide reference number KIMS/KIIT/IEC/209/2018 dated 14.12.2018.

For the diagnosis of associated complications, standard definitions were used as in other studies on scrub typhus [20,21]:

Acute kidney injury: A rise in serum creatinine of more than 1.5 mg/dL or urine output less than 400 mL/24 hours failing to improve after adequate rehydration.

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS): Bilateral alveolar or interstitial infiltrates on chest radiograph and PaO2/FiO2 less than or equal to 200 mmHg.

Hepatic dysfunction: Rise in serum Alanine Transaminase (ALT) and Aspartate Transaminase (AST) of more than three times the upper normal limit and/or elevation of serum bilirubin >3 mg/dL.

Meningitis: Altered sensorium with features of meningeal irritation like neck rigidity, positive Kernig sign with elevated protein and/or polymorphic leucocytosis on Cerebro-Spinal Fluid (CSF) analysis.

Shock: Systolic blood pressure of <90 mmHg for at least 1h despite adequate fluid resuscitation was labelled as shock.

Multiple-Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS): Dysfunction of two or more organ systems [12].

Statistical Analysis

The data analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.

Results

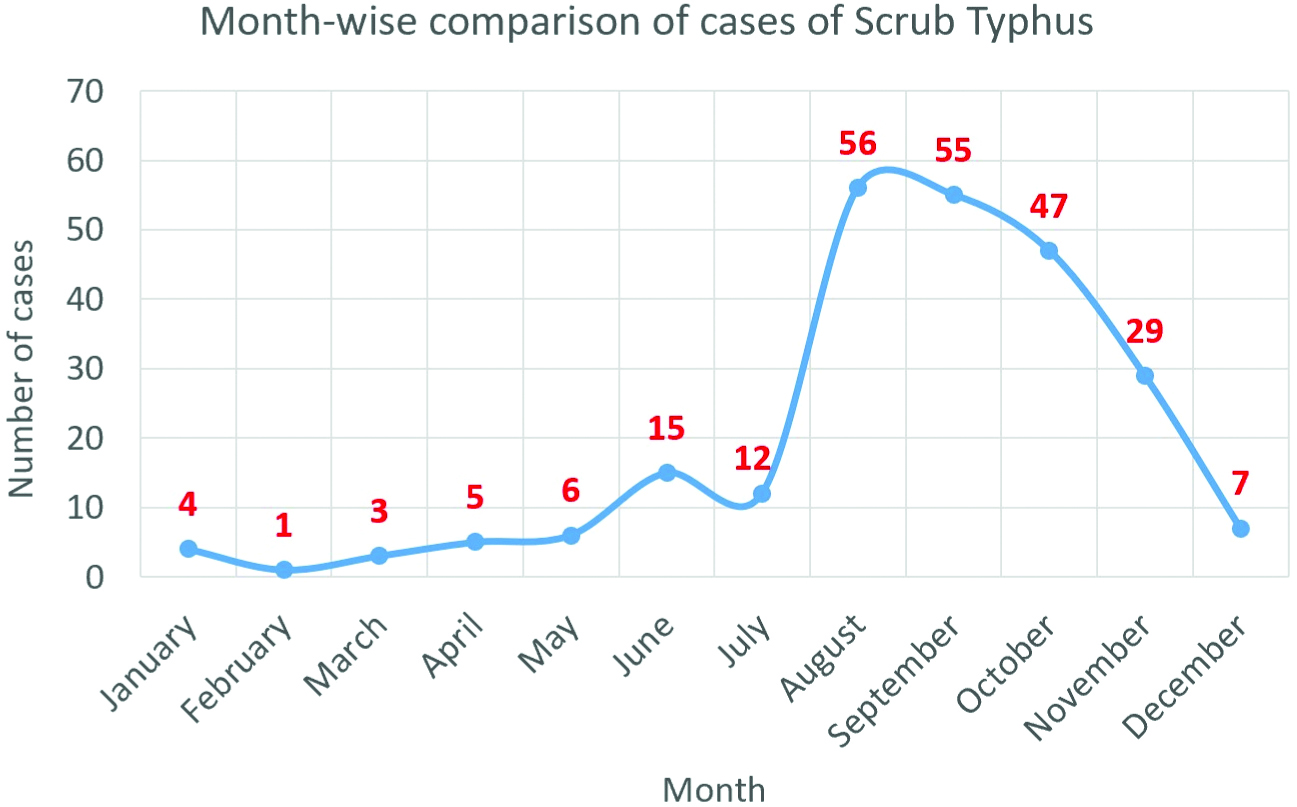

A total of 240 adult patients were diagnosed with Scrub Typhus between January 2016 to December 2018. Twenty-seven (11.3%) patients were diagnosed in 2016, 80 (33.3%) in 2017 and 133 (55.4%) in 2018. In the three years, 206 (85.8%) patients presented to the hospital between the months of July to December as compared to 34 (14.2%) patients between January to June. August and September were the peak months of presentation [Table/Fig-1].

Month wise comparison of cases.

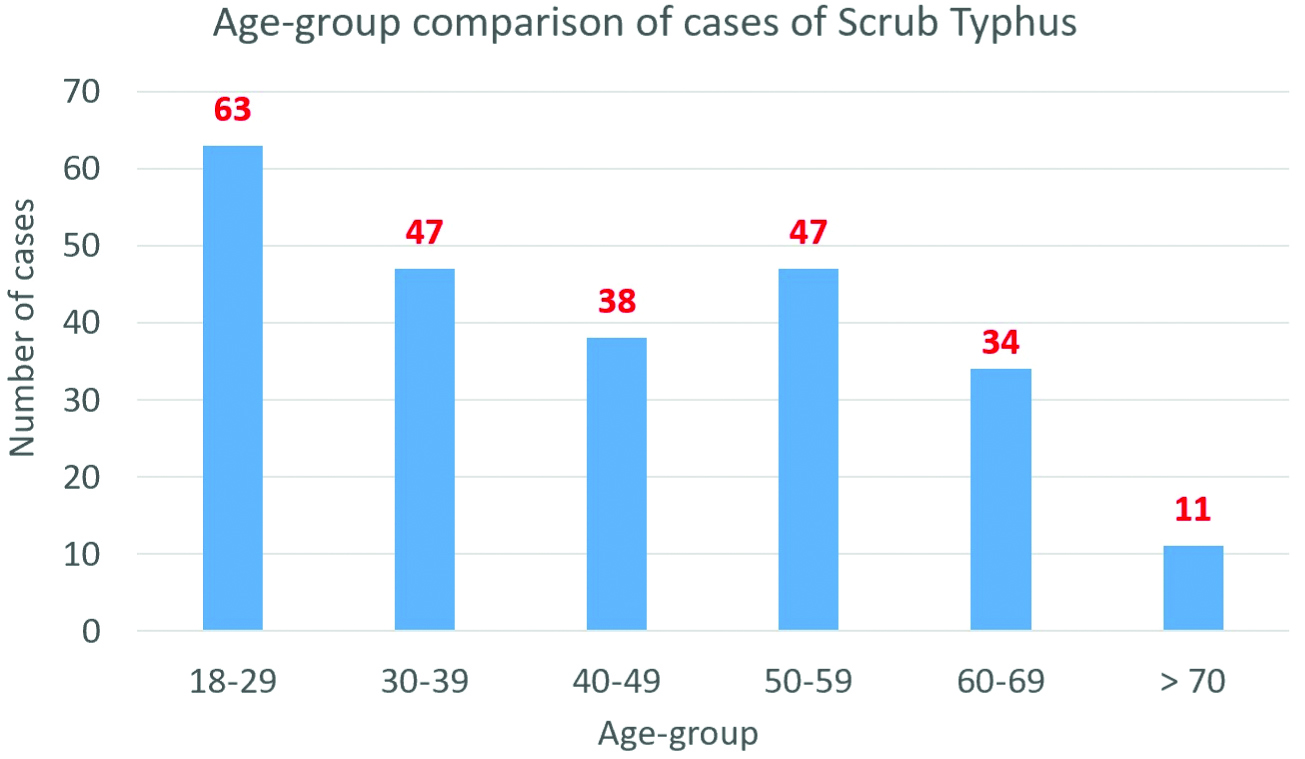

Demographic profile: One hundred thirty-one (54.6%) patients were males. The mean age of the patients was 42.34±16.46 years. Majority of the patients belonged to the age group of 18-29 years [Table/Fig-2]. One hundred ninety (79.2%) patients were from rural areas. Sixty-two (25.8%) patients had co-morbidities such as Diabetes Mellitus, Hypertension, Hypothyroidism, COPD or Rheumatoid Arthritis. Three (1.3%) patients were pregnant.

Age group comparison of cases.

Clinical manifestations: The most common symptom was fever. It was reported in 240 (100%) patients. At the time of presentation, 232 (97%) patients were found to be febrile [Table/Fig-3]. Forty-three (17.9%) patients were admitted in the ICU and remaining 197 (82.1%) patients were admitted in wards.

Clinical manifestations in this study.

| Clinical manifestations | ICU admissions | Non-ICU admissions | Total cases | p-value |

|---|

| Number of cases | 43 (100%) | 197 (100%) | 240 (100%) | |

| Symptoms |

| Fever | 43 (100%) | 197 (100%) | 240 (100%) | 1.0000 |

| Headache | 9 (20.9%) | 97 (49.2%) | 106 (44.2%) | 0.0007 |

| Vomiting | 16 (37.2%) | 73 (37.1%) | 89 (37.1%) | 1.0000 |

| Cough | 16 (37.2%) | 73 (37.1%) | 89 (37.1%) | 1.0000 |

| Breathlessness | 18 (41.9%) | 17 (8.6%) | 35 (14.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Bilateral leg swelling | 8 (18.6%) | 23 (11.7%) | 31 (12.9%) | 0.2170 |

| Altered sensorium | 16 (37.2%) | 11 (5.6%) | 27 (11.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Jaundice | 6 (14%) | 18 (9.1%) | 24 (10%) | 0.3977 |

| Rashes | 2 (4.7%) | 22 (11.2%) | 24 (10%) | 0.2672 |

| Decreased urination | 3 (7%) | 7 (3.6%) | 10 (4.2%) | 0.3911 |

| Abdominal distension | 2 (4.7%) | 2 (1%) | 4 (1.7%) | 0.1483 |

| Signs |

| Febrile | 37 (86%) | 195 (99%) | 232 (96.7%) | 0.0005 |

| Tachycardia | 22 (51.2%) | 73 (37.1%) | 95 (39.6%) | 0.2454 |

| Hepatomegaly | 17 (39.5%) | 59 (29.9%) | 76 (31.7%) | 0.2773 |

| Consolidation | 30 (69.8%) | 39 (19.8%) | 69 (28.8%) | <0.0001 |

| Splenomegaly | 9 (20.9%) | 37 (18.8%) | 46 (19.2%) | 0.8307 |

| Abdominal tenderness | 7 (16.3%) | 37 (18.8%) | 44 (18.3%) | 0.8294 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 0 | 37 (18.8%) | 37 (15.4%) | 0.0007 |

| Eschar | 0 | 34 (17.3%) | 34 (14.2%) | 0.0012 |

| Tachypnea | 14 (32.6%) | 9 (4.6%) | 23 (9.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Jaundice | 8 (18.6%) | 13 (6.6%) | 21 (8.8%) | 0.0313 |

| Low glasgow coma score (GCS<9) | 10 (23.3%) | 11 (5.6%) | 21 (8.8%) | 0.0010 |

| Neck stiffness | 5 (11.6%) | 11 (5.6%) | 16 (6.7%) | 0.1741 |

| Hypotension | 9 (20.9%) | 4 (2%) | 13 (5.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Ascites | 5 (11.6%) | 2 (1%) | 7 (2.9%) | 0.0024 |

| Pleural effusion | 2 (4.7%) | 4 (2%) | 6 (2.5%) | 0.2930 |

Respiratory involvement: Ninety-six (40.2%) patients had respiratory involvement during the initial presentation. Eighty-nine (37.1%) patients had cough, mainly dry in nature and 35 (14.6%) patients had associated breathlessness. On physical examination, 69 (28.8%) patients had consolidation and 6 (2.5%) patients were found to have pleural effusion. Eleven (4.6%) patients required mechanical ventilation due to ARDS and mean duration of ventilatory support was 4.5 days.

Gastro-intestinal and hepatic involvement: Eighty-nine (37.1%) patients complained of vomiting. Twenty-one (8.8) patients presented with jaundice. Seventy-six (32%) patients had hepatomegaly while 46 (19.2%) patients were found to have splenomegaly. Seven (3%) patients had ascites at the time of presentation.

Neurological involvement: One hundred six (44.2%) patients had headache and 27 (11.3%) presented with altered sensorium. Twenty-one (8.8%) patients presented with low GCS (<9) and showed elevated proteins with neutrophilic predominance in the CSF analysis.

Skin and soft tissue findings: Thirty-one (12.9%) patients had pedal oedema and 24 (10%) patients had maculopapular rashes. Eschar was seen in 34 (14.2%) patients, more commonly over the anterior aspect of the trunk. Thirty (12.5%) patients were found to have conjunctival congestion. Lymphadenopathy was seen in 37 (15.4%) patients, of which axillary lymphadenopathy was the most common.

Laboratory profile: The laboratory parameters were recorded on the day of admission (day 1), day 3 and day 7 in order to monitor the course of the illness. Leukocytosis (>10,000/mm3) with neutrophilia was the most predominant laboratory parameter [Table/Fig-4] which gradually improved on day 3 and day 7. On the day of admission, 15 (6.3%) patients had leukopenia (<4,000/mm3). Other parameters such as thrombocytopenia (<1,50,000/mm3), raised serum creatinine (>1.5 mg/dL), serum bilirubin (>3 mg/dL), raised serum AST (>120 IU/L) and serum ALT (>120 IU/L) also gradually improved by day 3 and day 7.

Day-wise comparison of laboratory parameters.

| Laboratory parameter | Number of cases |

|---|

| Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 7 |

|---|

| Leukocytosis | 108 (45%) | 41 (17.1%) | 9 (3.8%) |

| Leukopenia | 15 (6.3%) | 8 (3.3%) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 48 (20%) | 26 (10.8%) | 0 |

| Raised serum creatinine (>1.5 mg/dL) | 18 (7.5%) | 8 (3.3%) | 2 (0.8%) |

| Elevated serum bilirubin (>3 mg/dL) | 27 (11.3%) | 16 (6.7%) | 7 (2.9%) |

| Raised AST (>120 IU/L) | 59 (24.6%) | 25 (10.4%) | 6 (2.5%) |

| Raised ALT (>120 IU/L) | 44 (18.3%) | 12 (5%) | 5 (2.1%) |

AST: Aspartate Transaminase; ALT: Alanine Transaminase

By the day 7, 202 (84.2%) patients were discharged. Of the remaining 38 patients, 9 (3.8%) patients had persistent leukocytosis. Platelet count was normalised in all patients. Seven (2.9%) patients had persistent hyperbilirubinemia (>3 mg/dL), 6 (2.5%) had raised AST, 5 (2.1%) had raised ALT and 2 (0.8%) patients had raised serum creatinin, however these laboratory parameters were not mutually exclusive. Nine (2.5%) patients had normal laboratory parameters.

Associated complications: Liver dysfunction was the most common associated complication [Table/Fig-5]. Eighteen (7.5%) patients had acute kidney injury of which 2 (0.8%) required haemo-dialysis. Thirteen (5.4%) patients presented with shock of which 3 (1.3%) required vaso-pressors. Eleven (4.6%) patients had ARDS and required intubation. The mean duration of intubation was 4.5+1.4 days.

Associated complications with Scrub Typhus in this study.

| Complications | Number of cases |

|---|

| Liver dysfunction | 78 (32.5%) |

| Meningo-encephalitis | 21 (8.8%) |

| Acute kidney injury | 18 (7.5%) |

| Shock | 13 (5.4%) |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 11 (4.6%) |

| Multi-organ dysfunction | 21 (8.8%) |

Co-infections: The patients were also tested for other micro-organisms due to possibility of co-infection. Thirty-eight (15.8%) patients had co-infection, of which dengue was the most common which was found in 12 (5%) patients. All the co-infections that were found have been listed [Table/Fig-6].

Co-infections with Scrub Typhus in this study.

| Co-infection | Number of cases | Method of diagnosis |

|---|

| Dengue | 12 (5%) | NS1 and IgM ELISA |

| Urinary tract infection | 10 (4.2%) | Urine microscopy and culture |

| Plasmodium falciparum | 6 (2.5%) | Peripheral blood smear |

| Acute viral hepatitis E | 4 (1.7%) | IgM ELISA |

| Plasmodium vivax | 2 (0.8%) | Peripheral blood smear |

| Esophageal candidiasis | 1 (0.4%) | Upper GI endoscopy |

| Salmonellosis | 1 (0.4%) | Blood culture |

| Staphylococcus spp | 1 (0.4%) | Blood culture |

| Ventilator associated pneumonia (Acinetobacter spp) | 1 (0.4%) | Endotracheal tube culture |

Treatment outcome: Out of 240 patients, 237 (98.8%) were given oral Doxycycline. The remaining three patients were given oral Azithromycin because they were pregnant. Because of co-infections, 13 patients were given additional antibiotics, eight patients were given anti-malarial and one patient was given anti-fungal as per the antibiotic susceptibility testing reports. The response to doxycycline was noted with a decrease in frequency and intensity of febrile episodes within 48 hours. All the patients recovered from the illness. The mean duration of hospital stay was 8±3.7 days. The duration of stay in patients with co-morbidities was longer (9±4.1 days) than patients without co-morbidities (7±3.5 days). Of the 43 (17.9%) patients who were admitted in ICU, the mean duration of ICU stay was 5.2±1.9 days.

Discussion

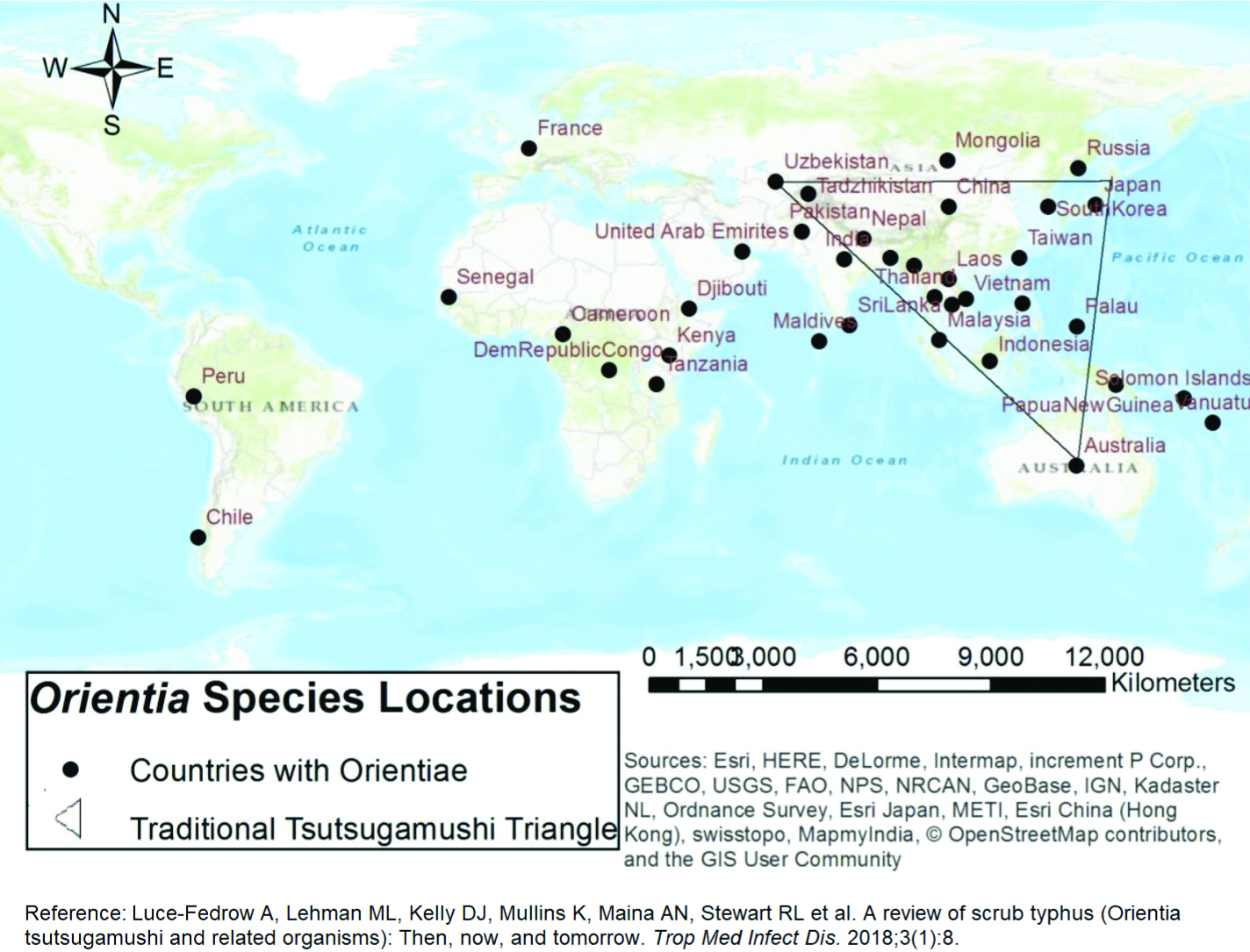

There has been a global re-emergence of scrub typhus which has affected people of vast geographical expanse [22]. There have also been reports of scrub typhus in newer areas such as Africa and South America by newly identified Orientia spp [Table/Fig-7] [23].

Distribution of Orientia species around the world [23].

Source: Esri, HERE, DeLorme, Intermap, increment P Corp., GEBCO, USGS, FAO, NPS, NRCAN, GeoBase, IGN, Kadaster NL, Ordnance Survey, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China (Hong Kong), swisstopo, MapmyIndia, OpenStreetMap contributors, and the GIS User Community

There has been a rising trend in the number of cases of scrub typhus over the last 3 years owing to the re-emerging nature of the disease and increasing clinical suspicion and reporting. August and September were the peak season of cases in this study which correlates with the rainfall pattern of the state of Odisha, India. Majority of the patients were between 18-29 years of age i.e., young adults. Around 54.6% patients were males, which may be due to exposure to outdoor/field work. Some studies in the Himalayan region have reported female predominance due to their contribution in domestic farming activities [24,25].

One of the diagnostic clues of scrub typhus is the presence of an eschar, a firm adherent necrotic black scab with an erythematous margin at the site of tick bite. It was seen in 14.2% patients in this study. It was similar to a study by Sharma N et al., in Chandigarh, India (14%), by Takhar RP et al., in Rajasthan, India (12%) and by Mahajan SK et al., in Himalayan region (9.5%) [26-28]. However, the presence of an eschar has been reported in 86.3%, 75.8% and 62.9% patients in China, South Korea and Vietnam, respectively [29-31]. This could be attributed to the dark skin of Indian patients as compared to fair skinned oriental patients making an eschar highly conspicuous in the latter.

In this study, lymphadenopathy was observed in 37 (15.4%) patients, of which 22 (9.1%) had axillary lymphadenopathy, 9 (3.8%) had cervical lymphadenopathy and 6 (2.5%) had inguinal lymphadenopathy. It was similar to a study in Chandigarh, India (11%) [26] and Rajasthan (18%) [27], but it was significantly different from a study in Meghalaya [21] where 52.5% patients had lymphadenopathy and 30% in a study from Pondicherry [32].

In this study, hepatomegaly was found in 76 (31.7%) and splenomegaly was found in 46 (19.2%) patients. In a study in Chandigarh, India, hepatomegaly was reported in 61% and splenomegaly in 45% patients [26] whereas a study in Rajasthan reported 34.8% patients with hepato-splenomegaly [27].

In this study, leukocytosis was seen in 45% patients on the day of admission. It was similar to a study by Hamaguchi S et al., in Hanoi, Vietnam (40.7%) [31]. However, it was reported in 13.5% patients in China [29]. Rest of the laboratory parameters were also compared [Table/Fig-8]. In this study, liver dysfunction (32.5%) was the most common complication followed by meningo-encephalitis (8.8%). A detailed comparison with other Indian studies was done [Table/Fig-9].

Comparison of laboratory parameters

| Author | Zhang M et al., [29] | Hamaguchi S et al., [31] | Jamil M et al., [21] | Present study |

|---|

| Study area | Shandong, China | Hanoi, Vietnam | Meghalaya, India | Bhubaneswar, India |

|---|

| Sample size | 102 patients | 237 patients | 61 patients | 240 patients |

| Laboratory parameter |

| Leukocytosis | 13.5% | 40.7% | 27.1% | 45% |

| Leukopenia | 4.1% | N/A | 5.1% | 6.3% |

| Thrombocytopenia | 25.4% | 45% | 32.2% | 20% |

| Raised serum creatinine (>1.5 mg/dL) | 3.7% | 11.5% | 27.1% | 7.5% |

| Elevated serum bilirubin (>3 mg/dL) | N/A | 7.7% | 27.1% | 11.3% |

| Raised AST (>120 IU/L) | 75% * | 97.5%* | 47.5% | 24.6% |

| Raised ALT (>120 IU/L) | 80.3% * | | 20.3% | 18.3% |

*Raised AST or ALT >40 IU/L; AST: Aspartate Transaminase; ALT: Alanine Transaminase

Comparison of associated complications.

| Author | Vivekanandan M et al., [32] | Jamil M et al., [21] | Takhar RP et al., [27] | Sharma N et al., [26] | Present study |

|---|

| Study area | Pondicherry, India | Meghalaya, India | Rajasthan, India | Chandigarh, India | Bhubaneswar, India |

| Sample size | 50 patients | 61 patients | 66 patients | 228 patients | 240 patients |

| Complications: |

| Liver dysfunction | 16% | 15.3% | 48.5% | 61% | 32.5% |

| Meningo-encephalitis | 14% | 8.5% | 7.7% | 5% | 8.8% |

| Acute kidney injury | 12% | 13.6% | 51.5% | 32% | 7.5% |

| Shock | 4% | N/A | 30.3% | 27% | 5.4% |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 8% | 11.9% | 51.5% | 25% | 4.6% |

| Multi-organ dysfunction | 34% | 16.9% | 48.5% | 20% | 8.8% |

In this study, patients with early presentation responded well to the treatment and required less days of hospitalisation in comparison to the patients who had delayed presentation or co-infections. The patients with known co-morbidities also had a slower recovery. Thus, geographical variation plays a role in the clinical manifestations and complications caused by scrub typhus and the recovery from the illness depends on duration of illness, co-morbidities and co-infections.

Limitation(s)

It was a retrospective analysis which constituted patients data from a tertiary care hospital. It might not be an exact representation of the illness in the community. At the same time, the authors solely relied on the accuracy of patient records which were obtained from the medical record department of the hospital.

Conclusion(s)

This study shows wide and varied presentation of Scrub Typhus infection along with the course of the disease and response to the treatment. The diagnostic clues such as fever, eschar, rashes and lymphadenopathy should be kept in mind by a primary care physician as early recognition and treatment can prevent its dangerous complications and reduce the mortality due to the disease. Occurrence of co-infections should also be kept in mind for better management of the patient.

AST: Aspartate Transaminase; ALT: Alanine Transaminase

*Raised AST or ALT >40 IU/L; AST: Aspartate Transaminase; ALT: Alanine Transaminase