In 2016, globally, cholera was the third leading cause of mortality due to diarrhoea among all ages (including children), responsible for about 107,290 deaths [5]. Cholera has been an important public health problem in India for many years. Between 2010 to 2015, as per surveillance by the Integrated Disease Surveillance Program, 24 states of India reported cholera and 13 states were classified as endemic [6].

There are a few studies and case reports in the literature which has investigated the clinical features and outcome of either V. cholerae O1 or V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139, but has not compared against each other [21-23]. Hence the present study was conducted with an aim to compare the clinical characteristics, laboratory profile and outcome of children with gastroenteritis due to V. cholerae O1 or O139 (also called as cholera) and V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 and to describe the clinical and laboratory profile and outcome of children bacteraemia due to V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study was conducted in Christian Medical College and Hospital (tertiary care institute), after the approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB: 11536 dated 26.09.2018). All children below 15 years of age who had V. cholerae isolated from the blood (bacteraemia) and/or stool (gastroenteritis) between January 2010 and November 2018 were included in the study. The data was collected during January 2019 to March 2019 of the children who reported to the institute between January 2010 and November 2018. The following details were noted: symptoms and signs (including vital signs and state of dehydration) at presentation, co-morbidities, anthropometry, complete blood counts, serum electrolytes, creatinine, reports of stool culture, blood culture and antibiotic susceptibility, details of treatment given (including hospital admission, IV fluids and antibiotics) and outcome. When any of the clinical or laboratory details mentioned above were missing in the records, those variables were excluded from calculations. As this is a retrospective study, no sample size calculation was done. When we considered dehydration and shock as the most important clinical feature of gastroenteritis, there was sufficient power of 99.3% to detect the difference among the groups. The standard of practice in the microbiology laboratory of this institution is as follows: stool samples sent for culture were studied for macroscopic appearance and a hanging drop done if it was watery. The sample was then plated on to Blood agar, MacConkey agar, Desoxycholate Citrate Agar, Xylose Lysine Desoxycholate Agar and if watery a Thiosulphate citrate Bile salts Sucrose Agar was added with Alkaline Peptone Water. The plates were incubated at 37°C aerobically for 18 hours. Any suspicious colonies were followed-up with preliminary screening biochemical media and confirmed for identity using specific antisera. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was done by the Kirby Bauer technique and results interpreted using Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [24].

Blood cultures were done using BacT Alert 3D system (Biomerieux) and identification using conventional media and biochemical reactions. The details of clinical features, laboratory profile, treatment and outcome were collected from the medical records.

Statistical Analysis

All the analysis was performed using STATA /IC 15.0 (Copyright 1985-2017 StataCorp LLC, Statistics/Data Analysis, StataCorp, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, Texas 77845 USA). Data were summarised using mean (SD)/median (IQR) for continuous variables and categorical data were expressed as frequency and percentage. The group-wise comparison for continuous variables was done using Independent t-test. The categorical data among the groups were compared using the chi-square test.

Results

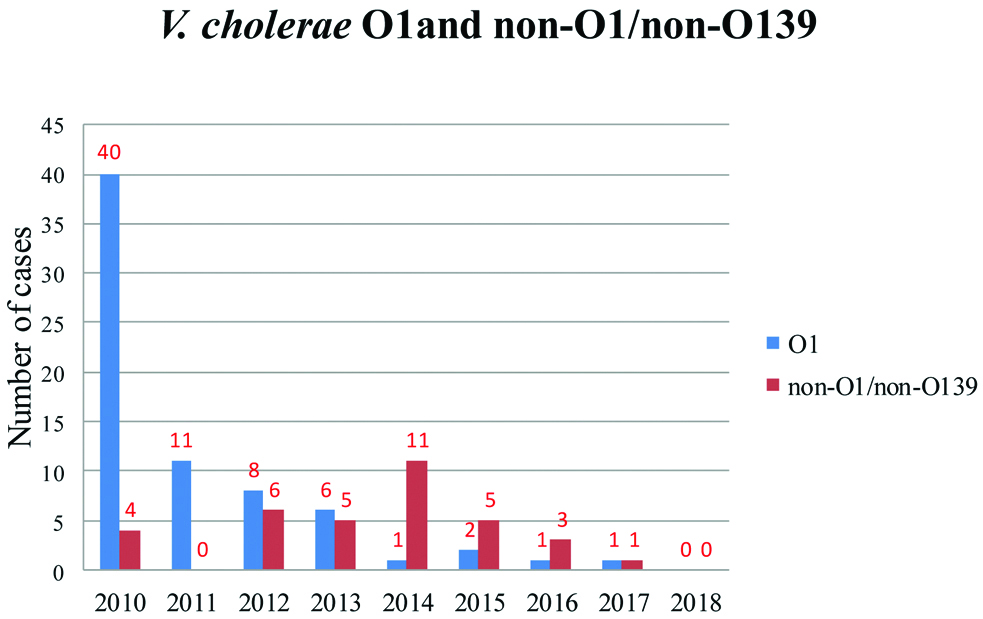

The total number of stool cultures and blood cultures done in children during the study period were 8,990 and 1,23,005, respectively. V. cholerae had grown in the stool culture of 105 children and the blood culture of six children. None of the children had both stool and blood culture positivity. The year-wise detection of V. cholerae gastroenteritis cases shows that the incidence of V. cholerae gastroenteritis is in a decreasing trend [Table/Fig-1].

Trend of V. cholerae O1 and non-O1/non-O139 gastroenteritis from 2010 to 2018.

Vibrio Cholerae Gastroenteritis

There were 68 (64.7%) boys and 37 (35.2%) girls. V. cholerae O1 had grown in stools of 70 children, V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 in 35 and V. cholerae O139 in none. The median age at diagnosis was 2.85 years (IQR: 1.4 to 6.0 years) for children with V. cholerae O1 and 1.3 years (IQR: 0.9 to 3.3 years) for children with V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 (p-0.005) [Table/Fig-2].

Description and comparison of clinical characteristics of the 105 patients with V. cholerae gastroenteritis (O1 and non-O1/non-O139) at presentation to hospital.

| | V. cholera O1 (n=70) | V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 (n=35) | p-values |

|---|

| Number available on records (n) | Percentage† | Number available on records (n) | Percentage† |

|---|

| Females (%) | | 70 | 29 (41.4%) | 35 | 8 (22.9%) | 0.06 |

| Median age in years (IQR)* | | 70 | 2.85 (1.4-6.0) | 35 | 1.3 (0.9-3.3) | 0.005 |

| Symptoms | Fever | 58 | 21/58 (36.2%) | 27 | 16/27 (59.3%) | 0.46 |

| Vomiting | 57 | 49/57 (85.9%) | 27 | 12/27 (44.4%) | <0.001 |

| Blood in stools | 58 | 2/58 (3.4%) | 27 | 17/27 (62.9%) | <0.001 |

| Abdominal pain | 58 | 6/58 (10.3%) | 27 | 2/27 (7.4%) | 0.666 |

| Lethargy/poor feeding | 58 | 30/58 (51.7%) | 27 | 2/27 (7.4%) | <0.001 |

| Seizures | 58 | 4/58 (6.8%) | 27 | 0/27 (0%) | 0.162 |

| Decrease in urine output | 58 | 23/58 (39.6%) | 27 | 5/27 (18.5%) | 0.054 |

| Co morbidities | | 56 | 17/56 (30.3%) | 30 | 8/30 (26.6%) | 0.719 |

| Respiration | Normal | 58 | 32/58(55.2%) | 30 | 27/30 (90%) | 0.001 |

| Tachypnoeic/acidotic | 26/58 (44.8%) | 3/30 (10%) |

| Degree of dehydration (WHO grading) [25] | No dehydration | 58 | 7/58 (12.0%) | 30 | 26/30 (86.6%) | <0.001 |

| Some dehydration | 13/58 (22.4%) | 2/30 (6.6%) |

| Severe dehydration | 25/58 (43.1%) | 2/30 (6.6%) |

| Shock | 13/58 (22.4%) | 0 |

| Weight for age Z score (IQR) | | 50 | -1.75 (-2.61, -0.88) | 29 | -1.05 (-1.65, -0.34) | 0.025 |

| Height for age Z score (IQR) | | 31 | -1.26 (-2.4,0.15) | 26 | -0.98 (-1.61, -0.98) | 0.470 |

p-value <0.05 significant;

*IQR: interquartile range; †Numerator is the number of children having that variable and denominator is the total number of children for whom details are available in medical records

Independent t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical data was used

Co-morbidities were present in 17/56 (30.3%) children with V. cholerae O1 and 8/30 (26.6%) with V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 (p-0.71) [Table/Fig-2]. The most common co-morbidity was protein energy malnutrition (n=5), followed by iron deficiency anaemia (n=4), leukaemia (on chemotherapy) (n=4), and post bone marrow transplant (on immunosuppression) (n=2).

The children with gastroenteritis with V. cholerae O1 had a significantly lower potassium level (p-0.04), and bicarbonate (p-0.02) and a higher creatinine (p-0.007) than V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 [Table/Fig-3].

Description and comparison of laboratory profile of children with V. cholerae gastroenteritis (O1 and non-O1/non-O139).

| | V. cholerae O1 (n=70) | V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 (n=35) | p-value |

|---|

| | Number available on records (n) | Percentage† or SD (as applicable) | Number available on records (n) | Percentage† or SD (as applicable) |

|---|

| Haemoglobin in g/dL (SD)* | | 29 | 10.92 (2.84) | 18 | 10.99 (1.93) | 0.928 |

| Total WBC (in cu mm)(IQR)‡ | | 30 | 12250 (IQR: 10700, 19200) | 18 | 11750 (IQR: 7200, 14800) | 0.163 |

| Neutrophils in % (SD) | | 28 | 61.89 (19.33) | 17 | 47.29 (24.12) | 0.030 |

| Lymphocytes in % (SD) | | 28 | 30.11 (17.92) | 17 | 43.12 (23.92) | 0.043 |

| Platelet count (lac/cu mm) (SD) | | 27 | 4.27 (2.03) | 17 | 2.69 (1.54) | 0.008 |

| Sodium (in meq/L) (SD) | | 56 | 134.5 (5.2) | 11 | 136.1 (2.9) | 0.327 |

| Sodium (in meq/L) (%) | <135 | 56 | 27/56 (48.2) | 11 | 3/11 (27.2) | 0.309 |

| 135-145 | 27/56 (48.2) | 8/11 (72.7) |

| >145 | 2/56 (3.5) | 0 (0) |

| Potassium (in meq/L) (SD) | | 56 | 3.23 (0.73) | 11 | 3.7 (0.63) | 0.048 |

| Potassium (%) | <3.5 | 56 | 41/56 (73.2) | 11 | 4/11 (36.3) | 0.092 |

| 3.5-5.0 | 14/56 (25.0) | 7/11 (63.6) |

| >5.0 | 1/56 (1.7) | 0 (0) |

| Bicarbonate (in meq/L) (SD) | | 28 | 11.57 (4.83) | 3 | 18.33 (1.53) | 0.024 |

| Creatinine (in mg/dL) (SD) | | 39 | 0.94 (0.55) | 12 | 0.48 (0.23) | 0.007 |

| eGFR (in mL/min/1.73 sqm) (SD) | | 22 | 52.98 (27.99) | 9 | 95.57 (47.85) | 0.005 |

| SGPT (in IU/L) (SD) | | 4 | 13.5 (4.36) | 8 | 15.5 (10.41) | |

p-value <0.05 significant

*SD: Standard deviation; †Numerator is the number of children having that variable and denominator is the total number of children for whom details are available in medical records; ‡IQR: Interquartile range

Independent t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical data

Among the 70 children with stool culture positive for V. cholerae O1, 50 had stool hanging drop test done and 16 out of 50 (32%) was positive. Six out of 35 with V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 infection had hanging drop test done and 1 (16.6%) was positive (p-0.44).

Thirteen children (18.5%) with V. cholerae O1 infection and 11 (31.4%) with V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 infection were co-infected with other bacteria (p-0.139). The bacteria that co-infected with V. cholerae O1 were Aeromonas (n=11), Shigella (n=1) and Salmonella C1 (n=1) and that with V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 were Aeromonas (n=5) and Shigella (n=6). However, there was no way to prove which one among the co-infection was responsible for diarrhoea.

Among the positive stool cultures which underwent susceptibility testing, V. cholerae O1 was resistant to nalidixic acid and cotrimoxazole in all (17/17) as against V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 where 5/9 (55.5%) were susceptible to nalidixic acid (p 0.001) and 6/9 (66.6%) to cotrimoxazole (p<0.001) [Table/Fig-4].

Drug susceptibility testing of V. cholerae isolates from stool culture.

| Drug sensitivity | V. cholerae O1 | V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 | p-value |

|---|

| Cefotaxime, n=26 | 17/17 (100%) | 9/9 (100%) | |

| Norfloxacin, n=26 | 17/17 (100%) | 9/9 (100%) | |

| Ampicillin, n=23 | 13/14 (92.8%) | 7/9 (77.7%) | 0.295 |

| Tetracycline, n=20 | 12/12 (100%) | 8/8 (100%) | |

| Nalidixic acid, n=26 | 0/17 (0%) | 5/9 (55.5%) | 0.001 |

| Cotrimoxazole, n=26 | 0/17 (0%) | 6/9 (66.6%) | <0.001 |

p-value <0.05 significant

Among the 105 children, 96 had the details available regarding hospital stay. A total of 55 out of 63 (87.3%) children with V. cholerae O1 infection and six out of 33 (18.1%) with V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 required hospital admission (p<0.001). The average duration of hospital stay was 3.27±1.69 days and 4.2±2.17 days for V. cholerae O1 and V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 respectively. About 56 out of 63 (88.8%) children with V. cholerae O1 and 5 out of 32 (15.1%) with V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 required intravenous fluids administration (p<0.001). The details of inpatient care of 1 child were not available. Among the 63 children with V. cholerae O1 infection, 2 required inotropes, 3 required oxygen, 2 required treatments in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and 1 required ventilation.

A total of 59 out of 63 (93.6%) with V. cholerae O1 and 31 out of 32 (96.8%) with V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 gastroenteritis were treated with antibiotics (p-0.362). 39 children among 59 (66.1%) with V. cholerae O1 and 8 out of 31 (25.8%) with V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 were given doxycycline alone (p<0.001). Doxycycline or doxycycline combination therapy was given for 57 out of 59 (96.6%) children with V. cholerae O1 and nine out of 31 (29.0%) with V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 (p<0.001).

Follow-up details were available for 97 children, 63 with V. cholerae O1 and 34 with V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 infection. All the 97 children recovered without any morbidity.

V. Cholera Non-O1/non-O139 Bacteraemia

There were six children with V. cholerae bacteraemia. The summary of the six cases is mentioned in [Table/Fig-5]. The age group of patients ranged from neonate to adolescent and four out of 6 (66.6%) were males. All patients had significant co-morbidities and the four out of 6 (66.6%) had liver disease. Despite treatment, three out of 6 (50%) succumbed to the illness.

Clinical and laboratory profile and outcome of the 6 cases of V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 septicaemia

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 |

|---|

| Age | 15 years | 10 years | 6 years | 7 months | 4 days | 5 years |

| Sex | Female | Male | Female | Male | Male | Male |

| Co-morbidity | Osteosarcoma-left humerus, on chemotherapy for 8 months | Wilson’s disease | Acute on chronic liver disease (unclear aetiology) | Neonatal cholestasis | Preterm (30+5 weeks)Only risk of sepsis: spontaneous premature onset of labour | Non Cirrhotic Intrahepatic Portal Hypertension (NCIPH) |

| Presenting symptoms | Fever | Fever, diarrhoea | Fever, lethargy | Fever, fast breathing, lethargy, irritability | Lethargy, brown nasogastric aspirates, haematochezia | Fever, abdominal pain |

| Duration of symptoms | 1 day | 1 day | 1 day | 1 day | 1 day | 1 day |

| Haemodynamic status | Normal | Compensated shock | Hypotensive shock | Hypotensive shock | Hypotensive shock | Normal |

| Hb (in g%) | 9.9 | 9.1 | 11.8 | 9.7 | 20.2 | 11.5 |

| Total WBC (in cu mm) | 3300 | 19600 | 5800 | 13500 | 16480 | 14500 |

| Differential count | N92 L8 | N61 L22 | N71 L28 | N76 L11 | N30 L56 | N86 L2 |

| Platelet count (in cu mm) | 1.14 lac | 1.53 lac | 45,000 | 72000 | 22000 | 1.09 lac |

| Sensitive to | Tetracycline, norfloxacin, ofloxacin | cotrimoxazole, ofloxacin, ampicillin, tetracycline, nalidixic acid and cefotaxime | Not done | Not done | Ampicillin, tetracycline, cotrimoxazole, cefotaxime, norfloxacin | Ampicillin, tetracycline, cotrimoxazole, cefotaxime, ofloxacin and ciprofloxacin |

| Resistant to | Cefotaxime, nalidixic acid, cotrimoxazole | Nil | Not done | Not done | Nalidixic acid | Nil |

| Treatment given | Ceftriaxone†, Gentamycin | Cefotaxime, followed by ceftriaxone.Doxycycline 1 dose | Meropenem | Cefotaxime followed by Piperacillin/Tazobactam and Amikacin | Meropenem, amikacin | Cefotaxime, doxycycline |

| Duration | 7 days | 10 days | 3 days | 2 days | 2 days | 10 days |

| Course of illness | No complications | No complications | Septic shock and DIC* | Septic shock and DIC | Refractory septic shock, MODS‡ and DIC | No complications |

| Outcome | Cured | Cured | Died on day 4 after admission | Died on day 2 after admission | Died on day 2 after the onset of symptoms | Cured |

*DIC: Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy

†Ceftriaxone was continued as the child had already shown improvement and gentamycin sensitivity was not done

‡MODS: Multiorgan dysfunction syndrome

Discussion

Among the 105 children with V. cholerae gastroenteritis, V. cholerae O1 was predominant (66.6%) compared to V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 (33.3%). A similar distribution was noted by Dutta D et al., in Kolkata, India (83.4 vs. 12.7%) [26].

There was a decreasing trend of V. cholerae gastroenteritis (both cholera and non choleragenic infection) over the study period of 2010 to 2018, which seems to be in a continuation of trend from the previous study done by Sebastian T et al., of the same institution (Christian Medical College, Vellore) from 2000 to 2010 [27]. This is probably due to decreased incidence of the disease itself, improvement of hygiene and use of ORS and antibiotics in the early course of the illness. The improvement of case management in a primary or secondary care facility could have reduced the need for referral to a tertiary centre. However incomplete reporting of cholera cases was always there [28].

Dysentery was a significant symptom in children with V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 gastroenteritis (62.9%, p<0.001) with a higher incidence than what was observed in a previous study done in Kolkata, India by Dutta D et al., [26]. The other symptoms like vomiting and lethargy occurred more often in children with V. cholerae O1 (p<0.001 for both symptoms) in present study which was comparable to the study done by Clemens JD et al., [29].

At presentation, the children with V. cholerae O1 gastroenteritis were significantly tachypnoeic/acidotic, dehydrated and in shock compared to V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 (p<0.001). This is expected when a child passes watery stools at the rate of 10-20 mL/Kg/hour and loses bicarbonate in the stools leading to acidotic breathing, dehydration, and shock [30].

The characteristic motility can be seen in stool hanging drop preparation and examination by dark field microscopy (sensitivity of about 50%) and it was done in about half of the total children (n=56) and only one-third (30.3%) had positive results. This is even lower than what was observed by Clemens JD et al., [29]. In stool cultures, co-infections (or mixed infections) with other bacteria like Aeromonas and Shigella were common in children (23.8%) with either type of vibrio gastroenteritis but there was a higher frequency of co-infection with V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 (31.4% vs. 18.5%; p 0.139), a finding consistent with previous studies [26,31,32]. The children with co-infections had a more severe form of gastroenteritis [33].

Antibiotic susceptibility: Both V. cholerae O1 and non-O1/non-O139 isolates were sensitive to cefotaxime, norfloxacin, and tetracycline. While V. cholerae O1 were all resistant to nalidixic acid and cotrimoxazole, V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 was partially sensitive to both (p<0.001). The pattern of drug susceptibility is not uniform in different parts of the world, even though there are some similarities [26,34-36].

The children with V. cholerae O1 infection were sicker at presentation and required hospital admission (87.3% vs. 18.1%, p<0.001) for management of dehydration, shock, and acidosis.

Almost all the children were treated with antibiotics (93.6% vs. 96.8%). The difference in antibiotic administration was due to the less severe diarrhoea and the presence of blood in stools in children with V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139. In our institution, authors continue to use doxycycline as the first-line antibiotic in suspected cholera based on the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommendation in 2010 of treating paediatric cholera with doxycycline (drug of choice) at a dose 2-4 milligrams/kilogram (mg/kg) in one dose [37].

V. Cholerae Non-O1/Non-O139 Bacteraemia

The youngest was a four-day-old preterm baby and the oldest was a 15-year-old girl. There are case reports in children of all age groups [13-20]. Every patient in this study had some form of significant co-morbidities [Table/Fig-5] which is similar to all the case reports available. The most noticeable fact is four out of 6 (66%) had Chronic Liver Disease (CLD). Chronic liver disease being a significant predisposing factor for V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 bacteraemia has been recorded in various studies in adult population [9,38], but not in paediatric population. Some suggest that patients who are immunocompromised and with CLD should not ingest raw seafood or expose skin wounds to saltwater [4].

Fever and lethargy were the predominant symptoms noted in these 6 patients, similar to all case reports [13-20]. A 66% of children had haemodynamic instability as has been documented before [13-20]. Antibiotic susceptibility of the isolated organism was done in four out of 6 cases. All 4 were susceptible to tetracycline and 3 were susceptible to ampicillin, cefotaxime, and cotrimoxazole. Based on the antibiotic susceptibility pattern, ampicillin, cefotaxime, and tetracycline are reasonable choices of initial empirical antibiotics.

The antibiotics used in different case reports were cefotaxime, penicillin, ampicillin, ciprofloxacin and imipenem [13-16,18]. Among the 3 survivors in the present study, cefotaxime or ceftriaxone were given for seven to 10 days. Based on the available data and study, one of the third generation cephalosporins (cefotaxime or ceftriaxone) seemed to be the most effective treatment [39]. In the case reports, the duration of intravenous antibiotics ranged from 10 days to 1 month [13-16,18]. Fifty percent of children in study succumbed to the illness in the first week of the illness itself. The outcome was unfavourable in younger children (especially infants, n=2) with bacteraemia. Among the 8 case reports available in literature, one child died [17], three survived without sequelae [13,16,20], two had severe neurological sequelae [15,18] and two did not have follow-up details. The younger infants including neonates were the ones who died or suffered severe neurological sequelae. This study has provided a description as well as for the first time, a comparison on clinical characteristics, laboratory profile and outcome of children with gastroenteritis due to V. cholerae O1 and V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139.

To the best our knowledge, this is the first-ever case series of V. cholerae non-O1/non-139 bacteraemia in the paediatric age group.

Limitation(s)

As the data were collected retrospectively from medical records, all the details with respect to clinical characteristics were not available.

Conclusion(s)

The gastroenteritis due to V. cholerae O1 was more severe than that with V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139. However, with appropriate management using fluids and antibiotics the prognosis was good. When diarrhoea due to V. cholerae is suspected, cefotaxime, norfloxacin or tetracycline should be the empirical antibiotics and not nalidixic acid or cotrimoxazole. The response to single dose doxycycline was excellent in the index patients.

With regards to V. cholerae non-O1/non-139 bacteraemia, children with chronic liver disease and immunodeficiency are particularly susceptible. In spite of administering appropriate antibiotics, 50% of the children succumbed to the illness and the younger ones had the worst outcome.