Catheterisation of central venous access has many purposes. It was being done with conventional landmark technique. Recently, use of USG for IJV cannulation deserved widespread implementation based on the strength of evidence in the literature. Usually, central lines are put in place by using anatomical landmarks, which often result in complications; while USG provides “real time” imaging. Many techniques for IJV puncture using anatomical landmark have been described [1]. Complications include formation of haematoma, occurrence of pneumothorax, puncture of the artery, improper cannulation into the thorax or soft tissues and even death. These complications are influenced by factors like expertise of the operator, site of attempted access and Body Mass Index (BMI) [2]. Recently, the use of USG for cannulation has been reported by many researchers to ease the procedure as compared to the landmark technique. It has been proposed that USG could decrease the number of complications, reduce the number of attempts and enhance the success rate [3,4].

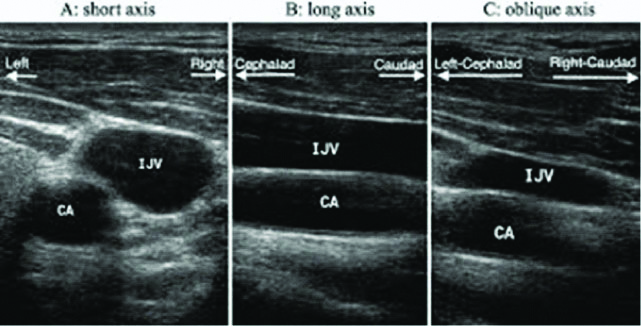

In the landmark approach, to put central venous catheter, central venous access is achieved by using surface anatomical landmarks and anatomical relationship of the vein to its palpable companion artery [5]. With the advent of USG, even an inexperienced physician is able to do IJV cannulation [6]. USG can be either static or dynamic. In static USG, vein is located and visualised in relation to surrounding structures prior to puncture. In dynamic real time USG, vein along with surrounding structures is visualised in real time prior to as well as during puncture. Dynamic guidance can be either in Short Axis View (SAX), Long Axis View (LAX) or medial Oblique View (OAX). SAX visualises the vessels in cross-section, LAX visualises them in the longitudinal view and OAX is a combination of SAX and LAX views [7].

Although many studies have been conducted regarding advantages of USG guidance over the landmark technique, few have used dynamic real-time USG for the same. Hence, this randomised controlled study was conducted to compare success rate, number of attempts, time required for a successful cannulation, and complications between USG guided IJV cannulation and conventional landmark technique.

Materials and Methods

The present randomised controlled study was conducted between March 2018 and October 2018 at Poona Hospital and Research Centre, Pune, India. After approval from the Scientific Advisory Committee (Letter No. RECH/SAC/2017-19/1165) and Institutional Ethics Committee (Letter No. RECH/EC/2018-19/1170), written informed consent was obtained from all patients. On the basis of a previously study [8], a sample size of 45 patients was calculated for each group by a formula with 80% power and 5% probability of Type I error to reject null hypothesis [9].

Patients who underwent major surgeries under general anaesthesia requiring central venous pressure monitoring, rapid infusion of fluids for major surgery, drug administration, and inadequate peripheral access were included. Patients who had infection at the local site, bleeding diathesis/ coagulopathy were excluded from this study.

The study was conducted in 90 patients with 45 subjects in each group. In Group A, IJV was cannulated with USG guidance using OAX whereas in Group B patients IJV cannulation was done by conventional landmark guided blind technique. Detailed pre-anaesthesia check-up was done one day prior to surgery. The procedure was explained in detail to the patients.

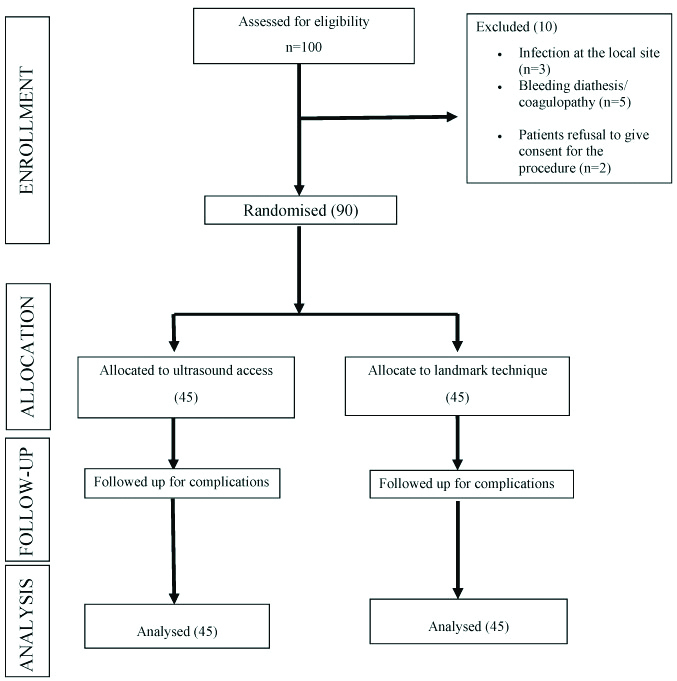

Patients were randomly allocated to USG guided IJV or conventional landmark method by computer generated randomisation codes [Table/Fig-1]. The patients were blind (single blind study) to the study. The randomisation code was allotted by the operation theatre nurse under the supervision of senior anaesthesiologist to the resident doctor who performed the procedure.

Upon arrival in the operating room, standard monitors such as Non-Invasive Blood Pressure (NIBP), ECG, and pulse oximeter were attached. A 20 G intravenous catheter was placed in a vein on the dorsum of the hand and ringer lactate infusion was started. Before anaesthetic induction, the blood pressure and heart rate were measured to find the baseline values. Patients were pre-medicated with injection ondansetron 4 mg and injection glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg Intravenously (IV). All the patients were given general anaesthesia, and injection midazolam 0.03 mg/kg IV and injection fentanyl 2 μgm/kg for sedation. After pre-oxygenation, a standardised general anaesthetic regime was employed, consisting of propofol 2 mg/kg and vecuronium 0.1 mg/kg with intraoperative non-opioid analgesia of paracetamol 15-20 mg/kg. Anaesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane 0.4 to 0.8 minimum alveolar concentration and 50% mixture of oxygen and nitrous oxide.

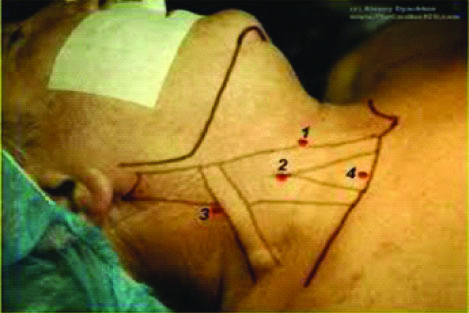

For the conventional landmark technique, the patient was placed in supine position. Trendelenburg position was given whenever feasible. The area was anaesthetised with 2% xylocaine solution with a 25 G needle. The anterior approach was used to access the internal jugular vein. In the Sedillot’s triangle, the carotid artery was palpated and retracted towards the midline. A 22G needle was inserted at the medial border of the sternal head of the sternocleidomastoid muscle with bevel facing-up, and the needle advanced towards the ipsi-lateral nipple, at 45 degrees angle with the skin surface [Table/Fig-2]. Location of internal jugular vein was identified by backflow of venous blood. If the vein was not entered by a depth of 5 cm, the needle was drawn back and advanced in a more lateral direction. Then the Y-site introducer needle was inserted along the same path as the 22G needle and venous blood aspirated to confirm vein location. After stabilising the needle, venous blood was confirmed by its dark colour and non-pulsatile nature. When free blood flow was achieved, the guide-wire with J tip on one end was introduced. The needle was removed and the dilator was advanced over the wire. The catheter was prepared for insertion by flushing all ports with saline, and all the proximal ports were clamped/capped except the distal one through which the wire had to pass. Then the dilator was removed and the final catheter advanced over the wire. The guide-wire was removed with the thumb placed over the catheter hub to prevent aspiration of air until the intravenous catheter tubing was connected to it. The catheter was then secured with silk suture and a sterile dressing was applied over it.

Landmarks for internal jugular vein cannulation.

1. Sternal head of sternocleidomastoid; 2. Clavicular head of sternocleidomastoid; 3. External jugular vein; 4. Superior border of medial third of clavicle

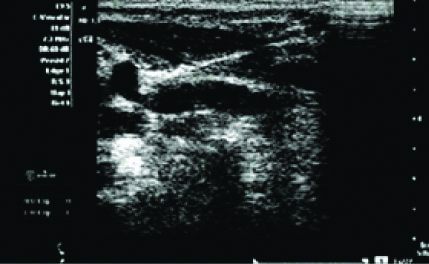

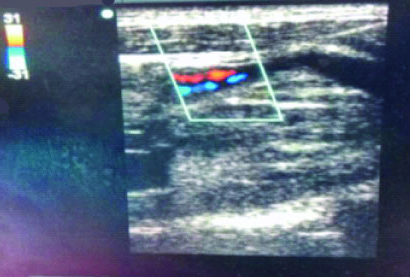

For ultrasound guided technique, linear probe (frequency 5-16 Hz) was used. The ultrasound probe was connected to the ultrasound unit, lignocaine jelly was applied over the probe and covered with sterile glove. In this study, the present authors saw the vessels in OAX view. Tip of the cannula was seen inside the elliptical shadow [Table/Fig-3]. On Doppler ultrasound, the carotid artery is encoded in red and shows flow towards the transducer. The internal jugular vein is seen in blue, with flow away from the transducer [Table/Fig-4]. Best view was obtained and the probe was fixed. Ultrasound imaging through Sedillot’s triangle demonstrated the carotid artery and the internal jugular vein as a circle and elliptical sonolucent shadow respectively [Table/Fig-5]. The vein was pricked with the Y cannula needle and the backflow was confirmed. The guide-wire was put through the Y cannula needle. The needle was then removed and the dilator was advanced over the wire. Then the dilator was removed and the final catheter was advanced over the wire. The guide-wire was removed. The catheter was secured with silk suture after confirming backflow from all the 3 ports and a sterile dressing was applied over it.

Internal jugular vein puncture by needle in oblique axis view.

Doppler ultrasound showing the carotid artery (red) and internal jugular vein (blue).

Different axis views for internal jugular vein cannulation under USG guidance.

Primary outcome measures were number of attempts, success rate, and the time required for a successful cannulation. Attempt was defined as the introducer needle’s entry into the skin and its removal from the skin. The patients who required >3 attempts were considered as failed attempts. Success rate was defined as placement of the central venous catheter with confirmation of backflow in all the ports of the triple lumen. Secondary outcome measures were incidence of complications, such as carotid artery puncture, haematoma, haemothorax, pneumothorax etc.

Statistical Analysis

Data were entered in Excel 2007. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 20.0 was used for analysis of data. Unpaired student’s t-test was used for the comparison of quantitative variables between the groups such as mean age, mean weight, mean height, mean BMI, mean duration of procedure. whereas chi-square test or Fisher’s-exact test was used for American Society of Anaesthesiologist (ASA) grade, comparison of qualitative variables such as gender, success rate, number of attempts and incidence of complications. The confidence limit for significance was fixed at 95% level with p-value <0.05.

Results

Out of 100 patients assessed for eligibility, 10 were excluded, because of infection at local site (3), bleeding diathesis/coagulopathy (5), and refused to participate (2) [Table/Fig-1]. In this study, a total of 90 patients undergoing major surgeries were recruited and were randomly allocated into two groups- 45 patients underwent IJV cannulation with USG guided technique (Group A) and 45 patient underwent with conventional landmark technique (Group B). There was no statistically significant difference between Group A and Group B in relation to mean age, gender, mean weight, mean height, mean BMI, and ASA grades [Table/Fig-6].

Baseline characteristics.

| Characteristics | Group A N=45 | Group B N=45 | p-value |

|---|

| Mean age in years±SD | 47.3±13.6 | 46.4±14.2 | 0.763* |

| Mean weight in Kg±SD | 61.4±8.9 | 60.2±5.9 | 0.450* |

| Gender (%) |

| Male | 22 (48.9) | 28 (62.2) | 0.203** |

| Female | 23 (51.1) | 17 (37.8) |

| Mean height in cm ±SD | 163.4±5.0 | 164.5±5.2 | 0.296* |

| Mean BMI in Kg/m2 ±SD | 22.9±2.8 | 22.3±1.9 | 0.200* |

| ASA grade (%) |

| Grade I | 20 (44.4) | 26 (57.8) | 0.421*** |

| Grade II | 22 (48.9) | 16 (35.6) |

| Grade III | 3 (6.7) | 3 (6.7) |

*Unpaired t-test was used; **Chi-square test was used; ***Fisher’s-exact test was used; BMI: Body mass index; ASA: American society of anaesthesiologist

Of the 45 cases in Group A, all were successfully cannulated. Of the 45 cases in Group B, 43 (95.6%) were successfully cannulated and 2 (4.4%) failed to cannulate in three attempts. The distribution of success rate did not differ significantly between two study groups. The percentage of patients who required ≥2 attempts was significantly higher in Group B compared to Group A. Mean time required for a successful cannulation, and incidence of complications were significantly higher in Group B compared to Group A [Table/Fig-7].

| Characteristics | Group A | Group B | p-value |

|---|

| Success rate (%) |

| Success | 45 (100.0) | 43 (95.6) | 0.494* |

| Failure | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.4) |

| Number of items |

| 1 | 44 (97.8) | 26 (60.5) | 0.001* |

| 2 | 1 (2.2) | 12 (27.9) |

| 3 | 0 (0.0) | 5 (11.6) |

| Incidence of complications (%) |

| Nil | 45 (100.0) | 33 (73.3) | 0.001* |

| Haematoma | 0 (0.0) | 8 (17.8) |

| Carotid artery puncture | 0 (0.0) | 4 (8.9) |

| Mean time required for the procedure in minutes±SD | 4.2±0.4 | 4.7±0.8 | 0.001** |

*Fisher’s exact test was used; **Unpaired ‘t’ test was used

Discussion

In the present study, successful cannulation was done in the first attempt in 97.8% and 60.5% patients in USG and conventional landmark technique respectively (p=0.001). The mean time required for a successful cannulation was 4.2 m and 4.7 m in USG and conventional landmark technique respectively (p=0.001). The complications were nil and 26.7% in USG and conventional landmark technique respectively (p=0.001). Success rate was 100.0% in patients with the USG guided technique as compared to 95.6% in conventional landmark technique, but there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups.

Turker G et al., and Palepu GB et al., reported that there was no statistically significant difference in mean age of landmark group 45.9 and ultrasound group 49.0 and landmark group 48.0 and USG group 49.3, respectively [1,10]. In the present study, the mean±Standard Deviation (SD) age of patients was 46.4±14.2 years, and 47.3±13.6 years in conventional and USG group respectively (p-value 0.763). Turker G et al., and Shrestha BR and Gautam B, reported that there was no statistically significant difference between male and female patients in landmark guided technique and ultrasound guided technique group for internal jugular vein cannulation [1,8]. These findings are similar to the present study.

Denys BG et al., reported that cannulation of the internal jugular vein was achieved in all patients, 302/302 (100%) using ultrasound and in 266/302 patients (88.1%) using the landmark guided technique (p-value <0.001) [11]. Cajozzo M et al., reported that the utilisation of USG guidance cannulation of the internal jugular vein was associated with significantly improved success rate (98.1%) compared to landmark technique (91.2%), (p-value <0.025) [12]. Shah H and Bhavsar M, conducted a prospective, randomised study in patients undergoing cardiac surgery who required IJV cannulation. They reported success rate of 95% with landmark technique group compared to 100% in ultrasound group (p-value <0.05) [13]. Mehta N et al., reported that in USG group success rate was 93.9% compared with the landmark group (78.5%) (p=0.02) [14]. All the previous studies showed that the success rate was higher for USG guided IJV cannulation compared to landmark technique. In the present study, in the USG group all 45 (100.0%) were successfully cannulated, whereas in the conventional group 43 (95.6%) were successfully cannulated (p=0.494).

In the present study, 60.5% of cannulations were accomplished in the first attempt in the landmark group as compared with 97.8% in the USG group. Palepu GB et al., reported that 72.7% cannulations were accomplished in the first attempt in the landmark group as compared with 84.4% in the USG group (p-value=0.004) [10]. Bansal R et al., reported that first attempt IJV success rate was 56.7% in landmark technique and 86.7% with the ultrasound guided technique [15]. In the present study, the percentage of patients who required ≥2 attempts was significantly higher in Group B compared to Group A (p-value <0.001).

Teichgräber UK et al., reported that the mean access time was significantly less with USG guided technique (15.2 seconds) compared with landmark technique (51.4 seconds) [p=0.001] [16]. Agarwal A et al., observed that mean time to successful insertion was significantly less in USG guided method (145 seconds) compared with conventional method (176.4 seconds) [p=0.001] [17]. Shrestha BR and Gautam B, reported that the mean time taken for successful cannulation was 4.9 minutes in USG approach and 8.0 minutes in the landmark group (p=0.001) [8]. In the present study, the mean±SD of the time required for the patients studied in the USG group and conventional group was 4.2±0.4 minutes and 4.7±0.8 minutes, respectively which was statistically significant (p=0.001).

Denys BG et al., reported that carotid puncture, brachial plexus irritation, and haematoma occurred in 1.7%, 0.4%, and 0.2% patients respectively in USG group while in the traditional landmark group, carotid puncture, brachial plexus irritation, and haematoma occurred in 8.3%, 1.7%, and 3.3% patients, respectively (p<0.001) [11]. Randolph AG et al., reported that USG guidance cannulation had lower rates of complications (relative risk 0.22, 95% confidence interval 0.10 to 0.45) compared with the standard landmark placement technique [3]. Cajozzo M et al., conducted a study to compare IJV cannulation with or without ultrasound guide. They observed that there were no major complications with the use of USG guide than without it. (0% vs 9.8%) (p-value <0.001] [12]. Bansal R et al., reported that the chances of occurrence of adverse outcome were significantly higher in the landmark procedure (p-value=0.020) [15]. Agarwal A et al., reported that 10% patients experienced arterial puncture and 2.5% pneumothorax in the conventional group whereas, the USG group had no complications (p-value <0.05) [17]. Shrestha BR and Gautam B, reported that carotid artery puncture occurred in 2/60 (3%) and 6/60 (10%) of patients in the USG guided and landmark group respectively (p<0.05) [8]. In the present study, of the 45 cases studied in the USG group, none had complications. Of 45 cases studied in the conventional group, 33 (73.3%) had no complications, 8 (17.8%) had haematoma and 4 (8.9%) had carotid puncture. The incidence of complications was significantly higher in conventional group compared to Group USG group (p=0.001).

Limitation(s)

There were some limitations to the study. The study did not include the length and circumference of the neck of the patients, which could be a confounding factor. All the cases were not performed by a single anaesthesiologist, thus differences in skills and anatomical knowledge could have affected the outcome.

Conclusion(s)

The mean time required for a successful cannulation, the number of attempts and the complications were significantly less with the use of USG guided technique compared to conventional landmark technique for IJV cannulation. Success rate was 100.0% in patients with the USG guided technique as compared to 95.6% in conventional landmark technique, but there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups.

*Unpaired t-test was used; **Chi-square test was used; ***Fisher’s-exact test was used; BMI: Body mass index; ASA: American society of anaesthesiologist

*Fisher’s exact test was used; **Unpaired ‘t’ test was used