Placenta Previa Partial Accreta Managed Successfully with Lower Segment Caesarean and Methotrexate Injection

Gowri Dorairajan1, Aghalya Muraliswaran2

1 Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Jawaharlal Nehru Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Puducherry, India.

2 Medical Student, Jawaharlal Nehru Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Puducherry, India.

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr. Gowri Dorairajan, 2nd Floor, Women and Child Block, Jawaharlal Nehru Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Puducherry-605006, India.

E-mail: gowridorai@hotmail.com

Placenta accreta is defined as an abnormal trophoblast invasion or pathologic adherence of part or all the placenta into the myometrium of the uterine wall. Patients with complete placental adhesive disorders are more likely to require classical caesarean and insitu hysterectomy or delayed hysterectomy during the postpartum period. The management of partially adhered placenta is controversial. We report a patient who was diagnosed to have partial adherence of the central previa placenta with intrauterine fetal demise. She was successfully managed by lower segment cesarean section after bilateral uterine artery ligation followed by excision of the non-adhered placenta and postoperative methotrexate. The operative and postoperative management is detailed. Lower Segment Caesarean Section (LSCS) and postoperative methotrexate should be considered a feasible and safe option for a woman with partial adhered placenta previa in the set up of a tertiary institute with intensive care unit and blood bank.

Hysterectomy, Placental adhesive disorders, Trophoblast invasion

Case Report

A 26-year-old second gravida was referred as a case of placenta previa at 34th week of gestation with gestational diabetes. She had a previous uneventful pregnancy and delivery of a term average size baby three years back. There was no history suggestive of manual removal of placenta. She had a spontaneous abortion two years back. There was no history of uterine curettage to complete it. There was no history of bleeding per vagina in this pregnancy. She was not hypertensive or anaemic. She was diagnosed to have mildly abnormal Glucose Tolerance Test (GTT) at 32 weeks. Her blood glucose levels were under control with diabetic diet.

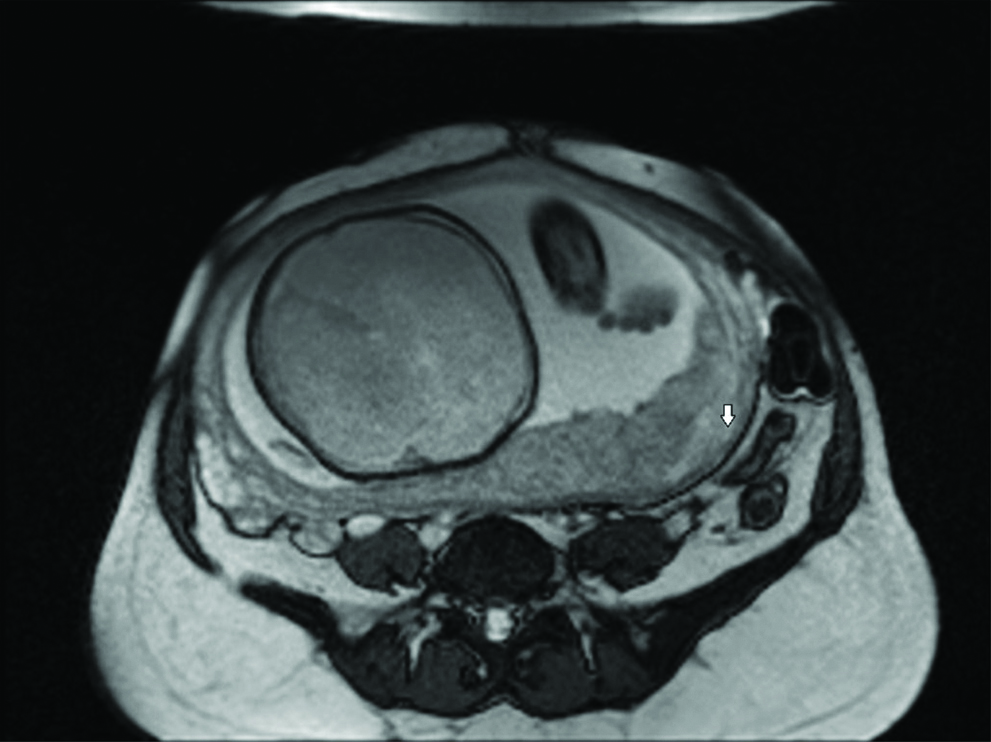

Ultrasound and MRI confirmed placenta type IV previa with 7 cm area of accrete in lateral wall of cervical region [Table/Fig-1]. She was kept in hospital and monitored for blood glucose levels and foetal well-being. The USG examination showed an optimally grown baby with normal liquor and non stress test. After 10 days of admission the women became less complaint with the diet (There was intake of sweets sent from home) and on the 10th day blood glucose levels became as high as 180 mg/dL postprandial. Two days prior her blood glucose levels were 93 mg/dL fasting and 118 mg/dL postprandial (monitored every 4th day). On the same day she complained of decreased foetal movements. Unfortunately, she had an intrauterine demise of the foetus detected clinically and confirmed by ultrasonogrpahy on the same day.

MRI image showing placenta accreta (arrow).

The couple was counselled regarding the placenta being low lying and adherent. They were counseled about the mode of delivery to be caesarean section in spite of foetal demise due to low lying and adherent placenta and the problems due to placenta accreta including the need for insitu hysterectomy. They were reluctant on hysterectomy as they were keen on another pregnancy.

After counselling and consent, and arranging for adequate blood and components and in consultation with the anaesthsiologists, elective caesarean section was planned and performed under general anaesthesia. Abdomen was opened by vertical midline incision. Since the foetus was already dead so bilateral uterine artery ligation was done first. As the patient was keen on another pregnancy and the placenta was covering the os, it was decided to incise the lower segment as high as possible. LSCS was successfully carried out without encountering the placenta. A good portion of the placenta was spontaneously separated. This separated portion was removed by clamping and cutting it away from the adhered chunk. The clamp was replaced by suture. No attempt was made to separate the adherent portion.

There was atonic postpartum haemorrhage that was managed with oxytocin, misoprostol and prophylactic internal iliac artery ligation. Two bottles of blood were transfused during operation. The baby weighed 2.7 Kg. There was no retroplacental haematoma or gross areas of calcification or infarction of the placenta in the separated portion. The intrauterine death was probably due to a sudden transient shoot up of blood sugar on the day of foetal demise. The baby was large for gestational age.

She was monitored in the ICU for 24 hours. The recovery was uneventful. Antibiotics were continued. The bleeding from vagina remained within normal limits. Methotrexate injection at 1 mg/Kg was administered in the postoperative period after 12 hours. The serum hCG level four days after delivery was 2071 and the repeat hCG levels in the serum after seven days was 1271 U/mL. The patient was kept in hospital till day 12. The sutures were removed on day 8 and wound healed well. She wanted to go home so she was discharged with advise to return in case of bleeding or pain or fever, etc.

Two weeks later she had spontaneous expulsion of the retained placenta. There was excessive vaginal bleeding. She was admitted and resuscitated. The os was open but cavity was empty. She was managed by cervical packing for 24 hours, antibiotics and blood transfusion. Repeat ultrasonography confirmed complete expulsion of the remaining placenta [Table/Fig-2a,b]. She resumed her normal periods after another four weeks.

Ultrasound image showing the retained placental bit.

Ultrasound image of uterus after expulsion of the placental bit.

Discussion

Similar to the index case two cases of partial accreta were successfully managed by Framarino-dei-Malatesta M et al., [1]. One of the cases had no previous live birth. Caesarean section was performed at 37 weeks and unadhered part of placenta was removed while leaving behind the adhered portion. This was followed by postoperative administration of methotrexate. This woman had a curettage earlier for an abortion. The second woman was keen on preserving uterus and caesarean was performed at 35 weeks.

Placenta accreta is defined as abnormal trophoblast invasion or pathologic adherence of part or all the placenta into the myometrium of the uterine wall. Previous caesarean section, advanced maternal age, multiparity, prior uterine surgeries or curettage, Asherman syndrome and IVF conceptions are the risk factors [2-4]. The incidence of placenta previa accreta spectrum is increasing from 24% after one caesarean section to 67% after four or more caesarean sections [5]. In present case, there was a spontaneous abortion two years back though there was no curettage.

Patients with complete placental adhesive disorders are more likely to require classical caesarean and insitu hysterectomy or delayed hysterectomy during the postpartum period. They have high morbidity and have longer hospital stays [6]. Life-threatening haemorrhage, requiring massive blood transfusion and injuries to adjoining organs like bladder and ureters during hysterectomy is the reason for increased morbidity and mortality.

Accreta Bundle formulated by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) [7] is recommended and should be strictly followed for completely adherent placenta previa accreta. Adherent placental conditions should be managed in an institution with multidisciplinary facilities including blood bank, anesthesiologist, expert obstetrician, urologist, etc. Classical caesarean section is recommended followed by insitu hysterectomy. This protocol of management is found to have lowest complication rates [8]. However, there is lack of consensus in managing partially adherent placenta previa during caesarean section. Management of placenta previa with partial accreta is still controversial and is evolving.

Recently, RCOG [7] has recommended LSCS and partial removal of placenta followed by balloon tamponade/uterine or iliac artery embolisation for previa with partial adherence with need to preserve fertility. Methotrexate has been sporadically used (though not recommended by RCOG) by a few. Complete resolution of placenta has been reported but increased need for hysterectomy within 30 days of caesarean is also reported with the use of methotrexate [9].

In a recent publication, out of the 26 women with placental adhesive disorder, 14 required caesarean hysterectomy. In the remaining 12 placentae was left insitu and postoperative uterine artery cannulation, injection of methotrexate in the uterine artery followed by uterine artery embolisation and postoperative intramuscular methotrexate was administered. Five women required hysterectomy. Rest of the seven women successfully expelled the placenta and resumed menstruation [10].

Conclusion(s)

Uterine conservation is possible in women with placental adhesive syndrome especially partial adhesion. Removal of the naturally separated portion of placenta and leaving behind the adhered part of placenta is feasible. Postoperative therapy in such cases with methotrexate is safe and results in spontaneous complete expulsion of the placenta. Such cases however should be managed in an Institution with round the clock facility for blood and components and intensive multidisciplinary care.

Author Declaration:

Financial or Other Competing Interests: None

Was informed consent obtained from the subjects involved in the study? Yes

For any images presented appropriate consent has been obtained from the subjects. Yes

Plagiarism Checking Methods: [Jain H et al.]

Plagiarism X-checker: Dec 31, 2019

Manual Googling: Jan 20, 2020

iThenticate Software: Feb 28, 2020 (12%)

[1]. Framarino-dei-Malatesta M, D’Amelio R, Piccioni MG, Martoccia A, Casorelli A, Conservative management of placenta accreta by systemic methotrexate: Report of two cases and review of the literatureJ Clin Case Rep 2016 6:70610.4172/2165-7920.1000706 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[2]. Usta IM, Hobeika EM, Musa AA, Gabriel GE, Nassar AH, Placenta previa-accreta: Risk factors and complicationsAm J Obstet Gynecol 2005 193(3 Pt 2):1045-49.10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.03716157109 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[3]. Eshkoli T, Weintraub AY, Sergienko R, Sheiner E, Placenta accreta: Risk factors, perinatal outcomes, and consequences for subsequent birthsAm J Obstet Gynecol 2013 208:219.e1-7.10.1016/j.ajog.2012.12.03723313722 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[4]. Bowman ZS, Eller AG, Bardsley TR, Greene T, Varner MW, Silver RM, Risk factors for placenta accreta: A large prospective cohortAm J Perinatol 2014 31:799-804.10.1055/s-0033-136183324338130 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[5]. Shellhaas CS, Gilbert S, Landon MB, Varner MW, Leveno KJ, Hauth JC, The frequency and complication rates of hysterectomy accompanying cesarean deliveryObstet Gynecol 2009 114:224-29.10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ad944219622981 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[6]. Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Thom EA, Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveriesObstet Gynecol 2006 107(6):1226-32.10.1097/01.AOG.0000219750.79480.8416738145 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[7]. Jauniaux E, Alfirevic Z, Bhide AG, Belfort MA, Burton GJ, Collins SL, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: Placenta praevia and placenta accreta: Diagnosis and management: green-top guideline no. 27aBJOG 2019 126(1):e1-48.10.1111/1471-0528.1530630260097 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[8]. Mitric C, Desilets J, Balayla J, Ziegler C, Surgical management of the placenta accreta spectrum: An institutional experienceJ Obstet Gynaecol Can 2019 41(11):1551-57.:pii: S1701-2163(19)30032-35[Epub 2019 Apr 2]10.1016/j.jogc.2019.01.01630948337 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9]. Fitzpatrick KE, Sellers S, Spark P, Kurinczuk JJ, Brocklehurst P, Knight M, The management and outcomes of placenta accreta, increta, and percreta in the UK: A population-based descriptive studyBJOG 2014 121(1):62-70.discussion 70-7110.1111/1471-0528.1240523924326 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[10]. Babaei MR, Oveysi Kian M, Naderi Z, Khodaverdi S, Raoofi Z, Javanmanesh F, Methotrexate infusion followed by uterine artery embolisation for the management of placental adhesive disorders: A case seriesClin Radiol 2019 74(5):378-83.Epub 2019 Feb 1010.1016/j.crad.2019.01.00630755315 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]