The FG is a fulminant form of progressive polymicrobial necrotising fasciitis of the perineal, genital, or perianal regions, caused by aerobic and anaerobic organisms. It commonly affects men, but women and children also may be affected [1]. Though this clinical entity is credited to Jean Alfred Fournier, a French venerologist, who described it in 1883 as a fulminant gangrene of the penis and scrotum in young men, Baurienne and Avicenna had independently described the same disease earlier in 1764 and 1877, respectively [2].

The infection usually starts from lower gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract or skin leading to thrombosis of cutaneous and subcutaneous vessels and necrosis of the affected region [2]. Hypoxia, obliteration of vessels and tissue oedema also favour the growth and proliferation of anaerobic bacteria. Tissue necrosis takes place quite rapidly and may even spread 2 to 3 cm per hour [3,4].

The clinical presentation varies from insidious onset with slow progression to rapid and fulminant course. It usually starts with erythema, swelling and pain followed by blister formation and gangrene. Crepitus is often present [5].

Much has been written about FG in the literature worldwide but less work has been done in the easternmost parts of India. Hence the work was undertaken to study demographic pattern of FG like age and sex of the patients, its predisposing factors and aetiological agents, locations of infective gangrene and outcomes in this geographical area.

Materials and Methods

This study retrospectively reviewed and analysed the records of patients with FG admitted and treated at the surgical wards of the Institute from July 2017 to June 2019. The following variables were collected: age, gender, aetiology, predisposing factors, duration of symptoms at admission, culture findings, antibiotic regimens, length of hospital stay and clinical outcomes. The vitals of the patients were noted from the record, particularly the level of consciousness, temperature, heart and respiratory rates and blood pressure. Laboratory parameters, such as white blood cell count, serum creatinine, albumin and bilirubin levels were also considered. Patients presenting with drowsiness, systolic pressure of less than 80 mm of Hg, white cell count of more than 15000/cu.mm and fever of more than 38°C were regarded as having septic shock. Mortality was defined as death related to FG during the hospital stay.

Statistical Analysis

Being a retrospective study, only standard descriptive statistics is reported in the results as percentages. No comparative statistical analysis was performed.

Results

Altogether the study included 14 patients admitted to the Institute during the study period. All the patients were male. Mean age was 54.57 years (range: 28-75 years). Most affected age group was the 6th decade with 5 (35.7%) patients in the group. Four (28.57%) of the 14 patients were between 61 to 70 years of age, 3 (21.43%) were in the age-group 41-50 years and 2 (14.29%) patients in the group 21-30 years. There was no patient in the age-group 31-40 years. The youngest patient in the study was a 28-year-old man. He had both HIV and Hepatitis C infections.

Diagnosis was based on clinical findings. All patients presented with swelling, redness and oedema of the perineal region with varying sizes gangrenous skin patches. Crepitation was felt in 3 (21.43%). In 4 (28.57%) cases, the infection had spread to the lower abdomen with 3 of them in septic shock state when presented.

Most common initial infection was an abscess in the perianal region. The infection seemed trivial in the beginning but progressed rapidly. The sites of initial infection are shown in [Table/Fig-1].

Sites of initial infection.

| Location | No. of cases | Percentage |

|---|

| Perianal abscess | 6 | 42.86% |

| Scrotal abscess | 3 | 21.43% |

| Perineal skin infections | 3 | 21.43% |

| Not-recorded | 2 | 14.28% |

| Total | 14 | 100% |

Most patients reported several days after onset of the disease ranging from 2 to 11 days, mean period being 6.7 days. As many as 11 (78.57%) patients had one or more co-morbid or predisposing conditions. Diabetes mellitus was the most common co-morbid condition with 9 (64.29%) cases. Of these 9 patients, 4 were alcoholic with CLD while 2 others had renal and cardiac complications. Altogether there were 7 cases with CLD, which included 4 cases with Hepatitis C infection. Three of the Hepatitis C positive cases had HIV also. No comorbid condition was defined in 3 cases [Table/Fig-2].

Co-morbid conditions associated with FG.

| Co-morbid conditions | No. of cases | Percentage |

|---|

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 | 64.27% |

| Alcoholic with Chronic liver disease | 7 | 50.00% |

| Hepatitis C infection | 4 | 28.57% |

| Hypertension/Cardiac disorder | 4 | 28.43% |

| HIV infection | 3 | 21.43% |

| Chronic renal failure | 2 | 14.29% |

| No co-morbid conditions | 3 | 21.43% |

Pus culture reported polymicrobial infection in all the cases. At least two organisms were isolated from the pus of every patient. Two patients grew three organisms each in their pus. Escherichia coli were the most common organism. One patient with CLD with HCV and HIV grew yeast buds on pus culture. The microorganisms isolated on cultures are shown in [Table/Fig-3].

| Organism | No. of patients | Percentage |

|---|

| Escherichia coli | 11 | 78.57% |

| Enterococcus | 6 | 42.87% |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 5 (2 MRSA) | 21.43% |

| Clostridia species | 3 | 21.43% |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 2 | 14.29% |

| Bacteroides | 2 | 14.29% |

| Proteus | 1 | 7.14% |

| Budding yeast | 1 | 7.1% |

All the patients underwent aggressive fluid resuscitation at the emergency department itself and were treated empirically with parenteral broad-spectrum antibiotics (third generation cephalosporin), an aminoglycoside (Amikacin) or a quinolone derivative (Ciprofloxacin) and metronidazole along with haemodynamic support when required. Mechanical ventilation and inotropic support were also applied when necessary. For the single patient whose culture grew “budding yeast”, parenteral Amphotericin B was also added. The patient had CLD with HCV and HIV, and apparently Amphotericin B was given to him empirically. According to the doctors who treated the patient, considering his immune-compromised state, yeast could be opportunistic, not normal flora of perineal skin in this case and low-dose amphotericin B was considered safe for the HCV infected liver, at least safer than other drugs like fluconazole. The patient died on the third day of start of the drug reportedly because of uncontrolled sepsis.

Aggressive debridement which meant surgical removal of all necrotic skin, subcutaneous tissue, fascia and non-viable muscles was done for all the patients except the one who could not be resuscitated. The wound was irrigated with hydrogen peroxide, then saline, and packed with dressings soaked in povidone iodine. Five patients required further debridement after two days while another two patients required debridement three times at two-day intervals. Debridement was done under local anaesthesia or without anaesthesia.

Five (35.71%) patients died in this study. All of them presented late (>6 days after onset of disease) with sepsis syndrome in addition to local signs of FG. All of them were diabetic. One of them was 75-year-old and could not be resuscitated and died on the second day after admission. Three others had CLD with Hepatitis C and while the fifth one had renal failure. Mean hospital days were 22.6 days, the longest stay being 35 days.

For the remaining 9 (64.29%) patients who survived, dressing as described above was continued till the tissue became healthy and viable, but wound closure by approximation of margins could be done only in three of them. The wounds of five other patients healed by secondary intention while for the remaining one patient, it was managed by a local flap. He required a split-skin graft also for the lost penile skin. No patient required colostomy or urinary diversion in the present study.

Discussion

In this study, it was found that co-morbidities like diabetes mellitus, CLD, HIV and HCV infection and CRF were present in 11 (78.57%) of the 14 patients. Most studies also observed that FG is more frequently found in men with poor hygiene, diabetes mellitus, paraplegia, cirrhosis and in alcoholics [3,6]. In this study, 64.27% of the patients were diabetic. In other studies also diabetes mellitus was the most common co-morbidity and was associated with 51%, 55.5% and 46% of their patients, respectively [5,7,8]. However, contrary to the majority, a few authors found the association of FG with diabetes mellitus in only about 20% of their cases [9,10].

FG is a polymicrobial infection. In the present study at least two organisms were isolated from the pus of every patient. This finding agrees with other studies which observed that FG was mostly a result of polymicrobial infection caused by aerobic and anaerobic organisms [5,9,11]. As in this study, E.coli was the commonest organism responsible for FG. Since the progress of FG is very fast, an effective surgical treatment and broad-spectrum antimicrobial combinations are very important and can determine the outcome of the disease [12,13].

For wound dressing and packing, povidone iodine was used in all the cases in the present study. Some authors prefer Dakin’s Solution (sodium hypochlorite) as it is supposed to have wide antimicrobial efficacy against aerobic and anaerobic organisms and significantly shortens the hospital stay [12]. The use of topical honey has also been described because of its ability to inhibit microbial growth likely related to the osmotic effect of its high sugar content [14].

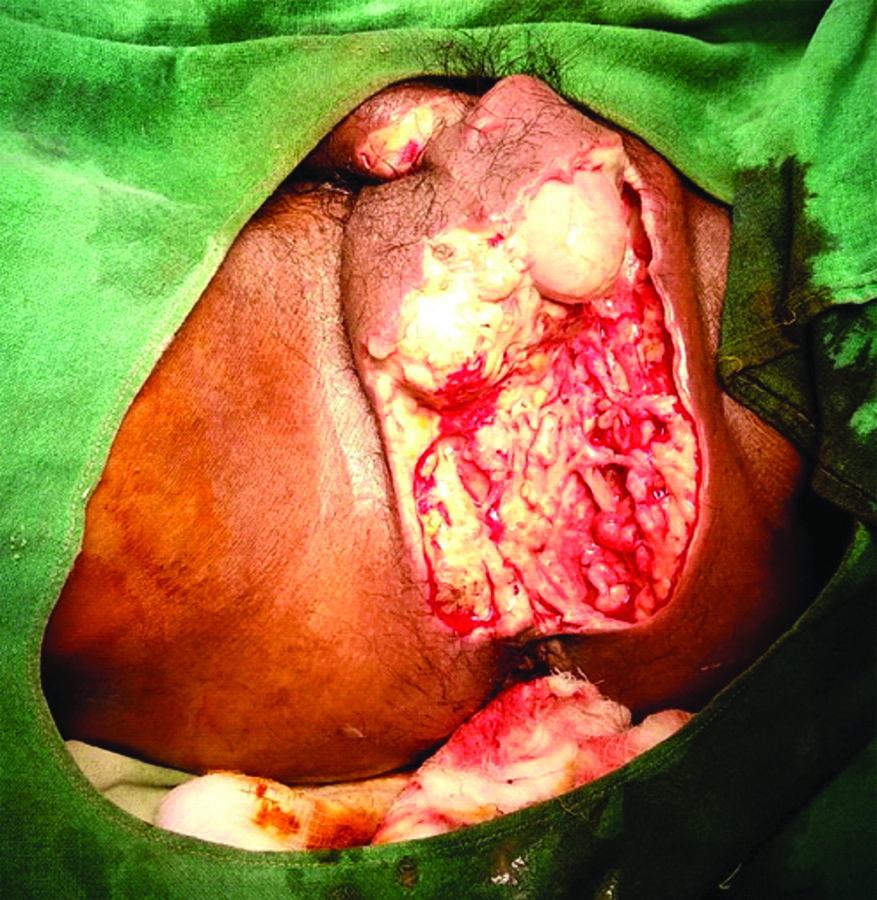

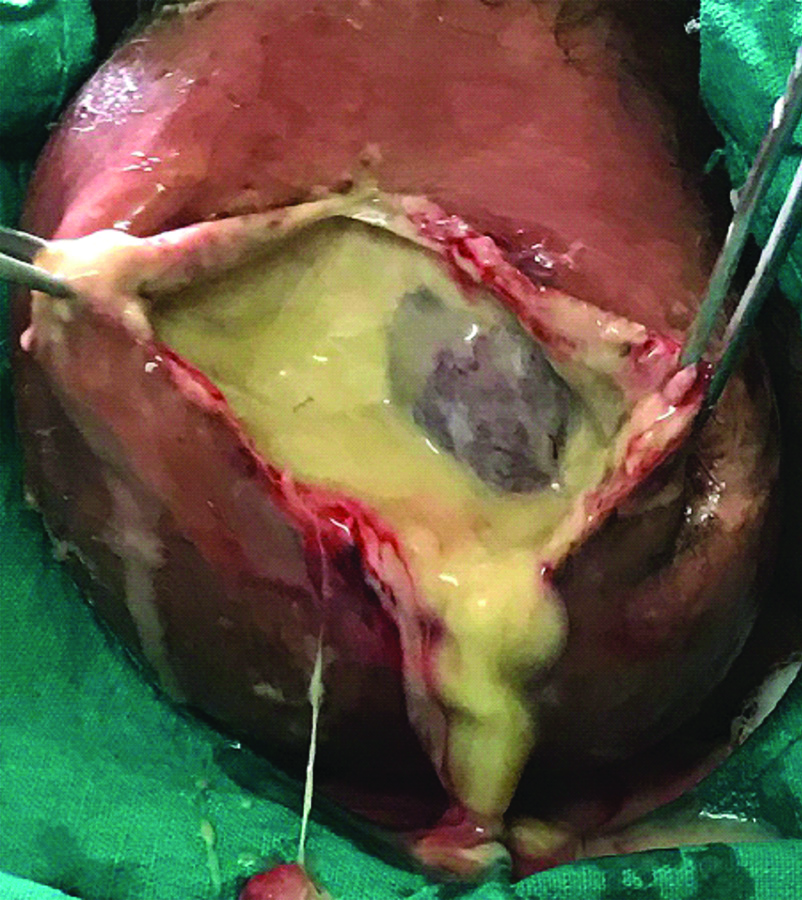

Testicular involvement or gangrene is not common in FG. In a well-known study [15] of 29 cases, orchidectomy was reported in only three cases, while in the two other series [1,11] orchidectomy was done only in 21% and 9.7% of their cases, respectively. In the present study also, testes were not affected even if scrotal skin had sloughed out [Table/Fig-4] except in one case whose testes were gangrenous [Table/Fig-5] and orchidectomy (bilateral) was done.

After debridement of wound of a case. Testes are partially exposed.

Gangrenous scrotum filled with pus. Testis is also gangrenous.

In most series, mortality is high in FG and many series [16-18] reported mortality rate of above 40% of their patients. The authors attributed the cause of the high mortality to late reporting at hospital and presence of sepsis, diabetes mellitus and other co-morbidities. The present study had similar observations and the mortality was 35.71%.

Limitation(s)

Since the number of cases is very small, statistical significance of this study is limited. FG Severity Index (FGSI) [19] which analyses temperature, heart and respiratory rates, levels of sodium, potassium, creatinine, bicarbonate, haematocrit and leukocyte count could not be done since this study was retrospective and did not have a standardised protocol.

Conclusion(s)

FG is a relatively rare necrotising fasciitis of the perineal and genital regions with an aggressive course. It is a polymicrobial infection which mainly affects those persons associated with immune-compromised conditions and co-morbidities, most importantly, diabetes mellitus. Extensive wound debridement, high doses of broad-spectrum antimicrobials and good supportive care are the mainstay of treatment. Mortality is high and is attributable to delay in treatment due to late reporting and presence of co-morbidities, especially diabetes mellitus.