Among the many potentially useful prognostic factors, familial susceptibility and ageing are considered increasingly relevant to screening. As much as 25% of patients with CRC have a positive familial history, with 15% having a family history in first or second-degree relatives [9]. There is also evidence that CRC in a close family member almost doubles the risk of CRC [6]. Similar patterns have been observed in the Iranian population [7], but compared with Western populations, epidemiological studies have shown that considerably more Iranians develop CRC at younger ages [7]. Colorectal cancer at age less than 40 years accounts for 20% of all cases of CRC in Iran, which contrasts unfavourably with the levels of 2%-8% in high-risk countries [8]. These findings suggest that broader efforts are needed to promote public health awareness and screening strategies in families with at least one person with CRC and that in Iran; this should extend to younger age groups.

The first country to implement an organised program was Germany in 1976, followed by the Czech Republic in 2000. Among Asian countries, Japan has conducted several cancer screening programs based on Guaiac-based Fecal Occult Blood Testing (FOBT) since 1992 [10], while Korea, China, and Hong Kong have had similar experiences with immunochemical FOBT [10]. By contrast, CRC screening has been limited in Iran, with studies focusing on program development and determining the potential benefits of these [11,12]. The recommended screening tests for CRC vary worldwide: FOBT is the main option in Europe and Canada, while sigmoidoscopy predominates in the UK and Norway and colonoscopy is used in Germany, Austria, Poland, and Italy [13,14]. According to an Asia-Pacific consensus statement, colonoscopy and FOBT are established screening options in Asia [15].

Implementing and administering CRC screening programs in different countries requires local epidemiological data about CRC. These include awareness of the prevalence, incidence, potential risk factors, affected age groups and characteristics of patients with moderate- to high-risk CRC; the severity of cancer at the time of diagnosis and the typical tumour locations; and the population attributed risk of CRC, the performance of risk assessment tools, and the estimated burden of CRC on people and public health. Clarifying these will help researchers develop a validated specific risk assessment tool to identify the most feasible screening methods that target the most vulnerable people.

Therefore the present study aimed to develop a feasible and efficient tool using NCCN Guideline, to improve risk assessment in CRC. The present authors also wanted to see if this could identify individuals with hereditary CRC, and thereby provide a modified plan for the diagnosis and prevention of cancer in these families. This risk assessment tool will be a simple, short and even self-administered, for scoring risk of CRC in normal population.

Materials and Methods

Design and Setting of the Study

This methodological study was conducted at the Hematology and Oncology Research Centre of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences from May 2016 to May 2017. It was anticipated that this tool could be used as a population-based and mass-screening instrument to identify people at moderate to high risk of CRC.

The ethics committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences has approved this project (IR.TBZMED.REC.1395.635), and all patients information and records are confidential.

Risk Assessment Tool

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline has been used for colorectal cancer screening that provides full details of CRC risk assessments that have been validated in many countries [16]. This tool for CRC screening stratifies individuals into three groups according to their attributed risk of CRC, which is based on a positive personal and/or family history of colon adenoma, CRC, and inflammatory bowel disease (i.e., ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease). Individual are grouped as follows:

Average risk: Individuals with a negative personal and family history of adenoma, polyps, CRC, or inflammatory bowel disease, and who are aged 50 years or older.

Increased risk: Individuals of any age with a personal history of adenoma, polyps, CRC, or inflammatory bowel disease, and those with a positive family history of CRC or with high-grade adenomatous polyps.

High-risk syndrome: Individuals with a family history of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC-1 or HNPCC-2) or with a personal or family history of polyposis syndrome.

Translational procedures: Language validity, Translation and back-translational were used to ensure language validity of the assessment tool. The original English version was translated into Persian by a certified translator under the supervision of the principal investigator, two medical oncologists, and a gastroenterologist.

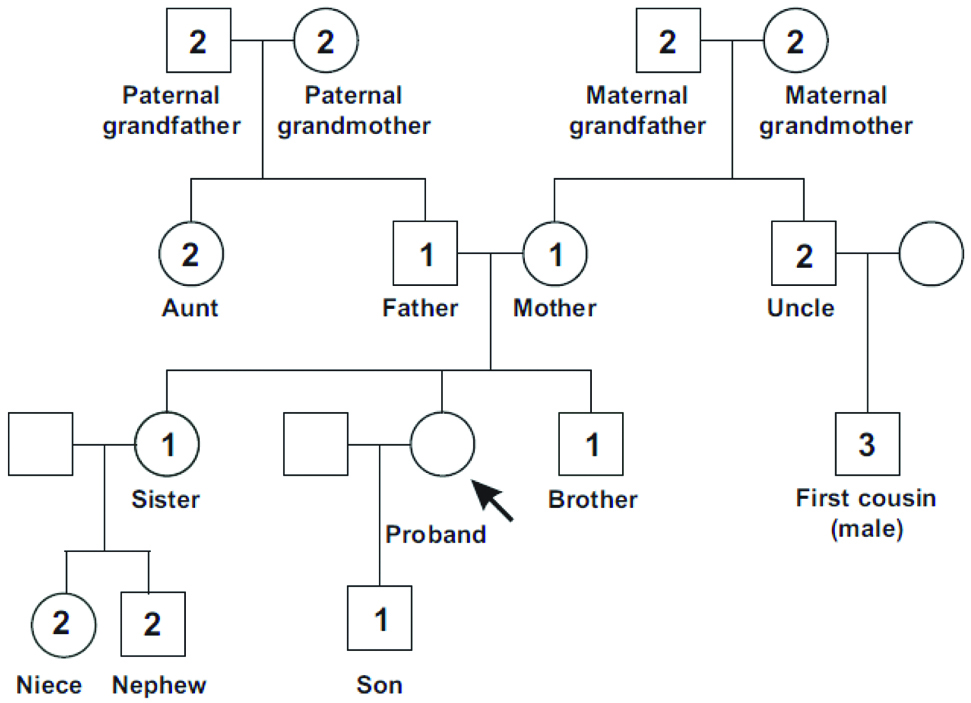

Content validity: To ensure that the risk assessment tool was accurate, we performed qualitative and quantitative analyses of content validity. First, we converted the tool to a self-inclusive questionnaire of 7 general items, 27 categories, and 40 subcategories covering the following: sex, age, personal history of high-risk syndromes, personal history of inflammatory bowel diseases, positive family history, and personal history of adenoma and polyps, and complete information about polyps. Each item included every detail of subcategories of the main item [Table/Fig-1]. A figure of an example pedigree that was added to the assessment to extract the family history of CRC in first, second, and third-degree relatives are shown in [Table/Fig-2]. Multidisciplinary panels of scientific judges were asked to offer their opinions about the risk assessment tool. This panel comprised five medical oncologists, three gastroenterologists, and two epidemiologists involved in CRC diagnosis, treatment, care, or research. The proportion of experts who agreed with the item relevance was quantified and reported as the Content Validity Index (CVI), before questionnaires were collected and the Content Validity Ratio (CVR) was calculated per item [17,18].

Comprehensive Assessment for Hereditary Colorectal Cancer Pedigree (First-, Second-, and Third-Degrees relatives of Proband).

Details of Risk Assessment, CVI, and CVR results from Questions’ Validation.

| Questions | Category | Subcategory | CVI | CVR |

|---|

| Sex | | | 1 | 1 |

| Age | | | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Personal history (based on colonoscopy or pathology report) | Adenoma | | 1 | 1 |

| Sessile Serrated Polyp (SSP) | | 1 | 1 |

| Colorectal cancer | | 1 | 1 |

| Acromegaly | | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Cronkite-canada syndrome | | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Personal history of inflammatory bowel diseases (based on colonoscopy or pathology report) | Chronic inflammation | | 1 | 1 |

| Ulcerative colitis | | 1 | 1 |

| Crohn’s diseases | | 1 | 1 |

| Irritable bowel disease | | 1 | 1 |

| Radiation colitis | | 1 | 1 |

| Personal history of high-risk syndromes (based on colonoscopy or pathology report) | Syndromes with Adenomatous Polyposis: {APC gene mutation (1%)} | Classical Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) | 1 | 1 |

| Attenuated Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (AFAP) | 1 | 1 |

| Gardner syndrome | 1 | 1 |

| Turcot syndrome (2/3 of families) | 0.90 | 0.80 |

| Syndromes with Adenomatous Polyposis: MMR gene mutations (3%) | HNPCC Type I | 1 | 1 |

| HNPCC Type II | 1 | 1 |

| Muir-Torre syndrome | 1 | 1 |

| MUTYH-Associated Polyposis (MAP) | 1 | 1 |

| Turcot Syndrome (1/3 of families) | 1 | 1 |

| Syndromes with Hamartomatous Polyposis | Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome (PJS) | 1 | 1 |

| Juvenile Polyposis Syndrome (JPS) | 1 | 1 |

| Bannayan-Ruvalcaba-Riley | 1 | 1 |

| Mixed polyposis | 1 | 1 |

| Cowden syndrome (PTEN) | 1 | 1 |

| Li-Fraumeni syndrome | | 1 | 1 |

| Serrated Polyposis Syndrome (SPS) | | 1 | 1 |

| Positive family history | ≥1 first-degree relative with CRC at any age | | 1 | 1 |

| ≥1 second-degree relative with CRC aged <50 y | | 1 | 1 |

| 1 first-degree relative with CRC aged ≤60 y | | 0.70 | 0.40 |

| First-degree relative with confirmed advanced adenoma(s) | | 1 | 1 |

| Familial colon-breast cancer | | 1 | 1 |

| Personal history of adenoma or SSP | Number | 1-3 polyps | 1 | 1 |

| 4-9 polyps | 1 | 1 |

| ≥10 polyps | 1 | 1 |

| Size | <1 cm | 0.90 | 0.80 |

| ≥1 cm | 0.90 | 0.80 |

| Subsite | Before splenic flexure | 0.80 | 0.60 |

| After splenic flexure | 0.80 | 0.60 |

| Morphology | Hyperplastic | 0.70 | 0.40 |

| Mucosal | 1 | 1 |

| Inflammatory pseudo polyp | 1 | 1 |

| Sub mucosal | 1 | 1 |

| Hamartomatous | 1 | 1 |

| Adenomatous | 1 | 1 |

| Serrated polyps | 1 | 1 |

| Endoscopic classification | Polyploidy | 1 | 1 |

| Sessile | 1 | 1 |

| Flat | 1 | 1 |

| Pedunculated | 1 | 1 |

| Pathologic classification | Tubular | 1 | 1 |

| Villous | 1 | 1 |

| Tubulo-villous | 1 | 1 |

| Staging | Stage 0 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Stage I: Minimal polyposis (1-4 Tubular Adenomas, Size 1-4 mm) | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Stage II: Mild polyposis (5-19 Tubular Adenomas, Size 5-9 mm) | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Stage III: Moderate polyposis (≥20 Lesions, or size ≥1) | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Stage IV: Dense polyposis, or High-grade Dysplasia, or Villous histology | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| Total mean | | | 0.93 | 0.92 |

Face validity: For the final step in validation, each item of the CRC risk assessment tool was assessed for face validity by 15 individuals, these were members of public, with age range of 40-60 years. They determined the feasibility and readability, as well as the clarity of the words, layout and style. Items were modified or expanded, if necessary, based on the comments received.

Statistical Analysis

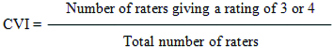

CVI: has been calculated as the number of “very relevant” (or 3-4) rating of experts for each question, by the total numbers of experts’ panel [19].

The simplicity, relevance, and transparency of each item were evaluated, and a CVI of ≥0.75 was considered valid [18].

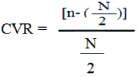

CVR: has been calculated for the essentiality of each question, where higher score (between 1 and -1) indicated higher agreement among expert panel members. In the formula, n=number of experts indicating “essential” for a question, and N=Total number of raters [19].

According to the Lawshe method, the critical CVR needed to be ≥0.62 given a panel size of ten experts [18].

Results

The translation was checked and validated by an expert research advisor, and the Persian-translated version was back-translated to English by an independent native English expert who was unaware of the original English text. At the final step, translation was reviewed and compared with the original English version to evaluate the quality of the translation. This ensured language equivalence and provided a culturally equivalent instrument with linguistic validity.

The experts rated each item for accuracy, simplicity and transparency to the content domain, and relevance to the Iranian population. According to experts’ recommendations, some questions required modification in categories and subcategories.

Although there was disagreement about the age distribution in the Iranian population, the experts ultimately unanimously agreed to categorise this item into two groups (<50 and ≥50-year-old). Question 4 was changed by moving radiation colitis from question 3 and by adding indeterminate colitis (inflammatory bowel disease). For question 6, first- and second-degree relatives and number of family relatives were included as subcategories. In question 7, subcategories for polyps were merged into three groups for the number (1-3 polyps, 4-9 polyps and ≥10 polyps) and two groups for the size (<1 cm and ≥1 cm). Because polyp subsite was deemed important for prognosis, we added the subcategory defining subsites before or after the splenic flexure. All changes recommended by the experts were implemented.

Based on experts’ opinions, the acceptable CVR was 0.40-1. Items that had a CVR <0.62 were removed according to the Lawshe guideline, and the CVI was calculated as 0.70-1. Moreover, the mean CVR and CVI values were 0.62 and 0.93, respectively.

Next, the face validity of the questionnaire was assessed, by 15 individuals, from normal population. Also, question 6 was updated to be multiple choices because more than one category might have applied to some cases. Also, in the designed pedigree, we changed the term “patient” to “case.”

Discussion

The original guideline for colorectal cancer screening (Version 1; May 22, 2017) [16] was used to design a questionnaire. Next, we translated the questionnaire from English to Persian and back-translated it to ensure language equivalence. The results of content validity, based on a scientific panel of judges’ opinions, indicated the reliability and completeness of the questionnaire, while the CVI and CVR were also well within the range of acceptability. The NCCN Guidelines for oncology have been successfully adapted and translated in other international settings, with the CRC screening guideline translated into Chinese, Japanese, Polish, Portuguese, Korean, and Spanish [20]. However, this is the first documented report of translation into Persian.

During an electronic search of data published about CRC screening guidelines, the present authors found a few articles about the validation and/or development of risk assessment models. Two of the identified models used numerical scoring systems [21,22]. In 2009, Kastrinos F., et al., also developed a simple pre-colonoscopy risk assessment tool to identify high-risk individuals, and developed a 34-item self-administered CRC Risk Assessment Questionnaire [23]. Their study was limited because it only sought to identify individuals at the highest risk for CRC, and because of most Centres screen high-risk individuals directly by colonoscopy. There were also two surveys in 2009 that sought to validate a CRC risk prediction tool and model based on guidance from the National Institute of Health. First, Freedman AN, et al., developed and introduced the risk prediction model, and constructed a short, simple, and self-administered questionnaire to use in those aged 50 years and older [24]. Despite developing a well-designed and comprehensive model, for which data were collected from two large US population-based studies, their model was not applicable to high-risk syndromes (e.g., Crohn’s diseases, familial adenomatous polyposis, and HNPCCs). Park Y et al., therefore sought to validate the risk prediction model by using data from a large population-based cohort study [25]. They evaluated the calibration and discriminatory power of Freedman AN, et al.’s CRC risk prediction model, and found it well calibrated and suitable for wider use, albeit with some limitations [24]. Notably, these studies were performed in the USA, in whites, and in limited age ranges (50-70-year-old), meaning that the model needs to be validated in other populations.

The development of an executive plan to identify the most appropriate screening method, target age group, and specific risk assessment tool is a priority in Iran. To date according to authors knowledge, few researchers have presented scoring systems for CRC assessment in Iran, and this study appears to be the first to generate and introduce risk assessment for CRC using a clinical practice guideline. There have been two independent surveys based on the psychometric properties of the “Health Belief Model” (HBM) scales for CRC screening, both of which aimed to assess the Persian version of HBM scales for Iranian beliefs about CRC, introducing a valid and reliable instrument to measure HBM constructs about CRC screening [26,27]. A qualitative survey was also performed by Zali MR et al., who used a grounded theory approach to compare results with Canada, Australia, and the United States. However, no clinical interactions were included in these studies [28].

The main advantages of the present tool are that it is comprehensive, based on clinically relevant NCCN Guidelines, and covers a wide range of CRC risk factors (e.g., age, personal history, familial history, and high-risk syndromes). However, published guidance should be followed when detecting CRC in people with high-risk syndromes and familial diseases; for example, to diagnose HNPCC-1 and HNPCC-2, the latest Bethesda guidelines need to be considered [29-32].

Limitation(s)

To identify high-risk syndromes, the present authors had to use the exact English terms, which may have been unfamiliar to individuals, because the autors could not translate them to Persian. However, it was assumed that volunteers with a history of these diseases diagnosed by a gastroenterologist or other specialist would know the correct term for the syndrome. The present authors also had to ensure correct answers from participants about personal and family histories of polyps, because colonoscopy should not be performed in all cases.

Also, formal genetic assessments are not always available in every centre and requests by specialists are often made by considering costs and difficulties, which were not of interest to us. Nevertheless, this study provides the first step to population-based CRC screening, offering a valid and practical risk assessment tool.

Conclusion(s)

The present authors developed and validated a feasible and efficient risk assessment tool by translating NCCN Guideline to Persian, while the NCCN Guidelines for oncology have been successfully adapted and translated in other international settings. The reliability and completeness of the questionnaire have been confirmed by scientific panel of judges’ for accuracy, simplicity and transparency to the content domain and relevance to the Iranian population.