Scrub typhus has been present in Southeast Asia since World War II, however, there has been a resurgence of the infection in India in the last few decades [2]. Although, scrub typhus is prevalent in Indian sub-continent there are very few evidences of its presence in other parts of the country especially in North and East India. There is a very low level of awareness regarding the scrub typhus infection among doctors and therefore the index of suspicion among the clinicians, especially private medical practitioners in rural areas is far lower for scrub typhus infections [3]. There are however many cases reported among the paediatric age group while very few cases are documented in the adult populations. In addition, studies have reported an overall mortality between 7 and 30% for scrub typhus which is fairly higher compared to other infections and zoonotic diseases [4].

Apart from the increased mortality, the scrub typhus infection is also associated with the high risk of complications namely multiorgan dysfunction. There are studies which have documented impairment of the nervous system and renal system but there are few cases which have documented multiorgan dysfunction as a consequence of acquired scrub typhus infection [5].

There is paucity of information regarding the clinical presentation and the pathophysiological manifestation of scrub typhus infection, especially in tropical regions in Southern India. Therefore, this study was carried out in order to substantiate the clinical manifestation of this infection so as to sensitise the primary clinicians regarding the scrub typhus infections. The significance of evaluating scrub typhus in tropical countries like India stems from the fact that the disease is widely distributed in the tsutsugamushi triangle which comprises of various countries in the Asia Pacific region including Japan, China, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and southern parts of Russia [6]. This study was carried out to determine the clinical profile and manifestation of scrub typhus infection among rural adults in Puducherry, India.

Materials and Methods

This Retrospective study was conducted in the Department of General Medicine in a tertiary care hospital from January 2015 to December 2015. The case records of all the adults who were admitted with scrub typhus infection during the study period were included in the study, after due approval from the institutional ethical board. All the procedure have been followed according to the Deceleration of Helsinki.

Inclusion Criteria

Adult patients who were positive for IgM antibody for scrub by Immunochromatography (ICT).

Exclusion Criteria

Clinical confirmation of any other co-existing febrile illness like malaria, dengue or any other tropical diseases, children <18 years of age, case records with insufficient/incomplete medical data.

Sample Size and Sampling Technique

A total of 94 cases were recorded in the year 2015. Among the 94 cases, immunochromatography for IgM positivity was present in 86 cases. Out of the 86 cases, 7 cases were excluded due to incomplete data. Analysis was carried out on a total of 79 cases.

Data Collection Tools

Data were collected from the medical records departments. The background profile regarding age and sex of the individuals were documented. The clinical presentation, physical examination and laboratory parameters were documented. The course in the hospital in terms of the duration of hospital stay, treatment given and patient outcomes were also documented.

Statistical Analysis

Data were entered and analysed using SPSS version 15.0 software. The clinical presentation was expressed in terms of presentations. Chi-square test was used to analyse the statistical significance of demographic characteristics with clinical manifestations. Independent sample t-test was used to determine the association between the means of the parameters and the clinical manifestation. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

This study was carried out among 79 hospital admissions. Majority of the participants were males (60.8%) and were less than 40 years of age (55.7%). Fever was the predominant symptom (49.4%) followed by headache (38%) and cough (19%) [Table/Fig-1].

| Characteristics | Frequency (N=79) | Percentage (%) |

|---|

| Primary symptoms* |

| Fever | 39 | 49.4 |

| Headache | 30 | 38.0 |

| Cough | 15 | 19.0 |

| Generalised body pain | 15 | 19.0 |

| Breathlessness | 29 | 36.7 |

| Other symptoms* |

| Ulcer | 17 | 21.5 |

| CNS symptoms | 16 | 20.3 |

| Swelling of feet | 1 | 1.3 |

| Joint pain | 2 | 2.5 |

| Tinnitus | 1 | 1.3 |

| Jaundice | 2 | 2.5 |

| Abdominal symptoms |

| Present | 30 | 38.0 |

| Absent | 49 | 62.0 |

| Type of abdominal symptoms (n=30) |

| Nausea | 8 | 26.7 |

| Vomiting | 5 | 16.7 |

| Loose tools | 7 | 23.3 |

| Abdominal distension | 1 | 3.3 |

| Pain abdomen | 7 | 10.1 |

| Epigastric pain | 1 | 3.3 |

| Malena | 1 | 3.3 |

*the figures will not total to 100

Almost all the participants had clinical hyperthermia (98.7%), about 17.7% of the participants had abnormal respiratory signs, splenomegaly was present in 12.7% of the participants [Table/Fig-2].

| S. No. | Parameter | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|

| 1 | Vital signs |

| Tachycardia | 36 | 45.6 |

| Hypertension | 7 | 8.9 |

| Fever | 78 | 98.7 |

| Tachypnea | 1 | 1.3 |

| 2 | General examination |

| Pallor | 18 | 22.8 |

| Icterus | 2 | 2.5 |

| Pedal oedema | 2 | 2.5 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 7 | 8.9 |

| Eschar | 13 | 16.4 |

| 2.1 | Eschar location (n=13) |

| Left axilla | 1 | 7.7 |

| Right hypchondrial region | 2 | 15.4 |

| Right elbow | 1 | 7.7 |

| Right axilla | 1 | 7.7 |

| Left hypchondrium | 2 | 15.4 |

| Anterior abdominal wall | 2 | 15.4 |

| Sacral region | 2 | 15.4 |

| Left inguinal region | 1 | 7.7 |

| Right iliac fossa | 1 | 7.6 |

| 3 | Systemic examination |

| Abnormal signs of cardiovascular system | 0 | 0 |

| Abnormal signs of respiratory system (RS) | 14 | 17.7 |

| 3.1 | Specific respiratory system signs (n=14) |

| Bilateral crackles and rhonchi | 9 | 64.4 |

| Bilateral wheeze present | 3 | 21.4 |

| Right lower zone pneumonia | 1 | 7.1 |

| Bilateral crepitations and right side pleural effusion | 1 | 7.1 |

| 3.2 | Specific abdomen signs | 17 | 21.5 |

| Hepatomegaly | 7 | 8.9 |

| Splenomegaly | 10 | 12.7 |

| 3.3 | Specific signs of Central Nervous System (CNS) | 6 | 7.6 |

| Agitate and restless | 3 | 50.0 |

| Features suggestive of meningo-encephalitis | 1 | 16.6 |

| Auditory hallucination | 1 | 16.7 |

| Drowsy | 1 | 16.7 |

Among the study participants, low total white blood cell counts were seen in 63.3% and elevated total white blood cell counts were seen in 17.7% of the participants, while thrombocytopenia was present in 49.4%. Abnormal urine analysis was seen in 3.8% of the participants. About 44.3% of the participants have urine albumin in traces. Chest radiograph was largely normal and only one participant showed presence of bilateral nodular shadows [Table/Fig-3].

| Characteristics | Frequency (N=79) | Percentage (%) |

|---|

| Total count |

| Low (<4000 cells/cumm) | 50 | 63.3 |

| Normal (4000-11000 cells/cumm) | 14 | 17.7 |

| High (>11000 cells/cumm) | 15 | 19.0 |

| Platelet count |

| Thrombocytopenia (<150,000 cells/mcL) | 39 | 49.4 |

| Normal (100,000-450,000 cells/mcL) | 40 | 50.6 |

| Urine analysis* |

| Abnormal | 3 | 3.8 |

| Normal | 76 | 96.2 |

| Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) |

| Abnormal | 1 | 1.3 |

| Normal | 78 | 98.7 |

| Chest radiograph |

| Bilateral nodular shadows | 1 | 1.3 |

| Normal | 78 | 98.7 |

*one or more of abnormal urine analysis including proteinuria, glucosuria, presence of pus cells, red blood cells

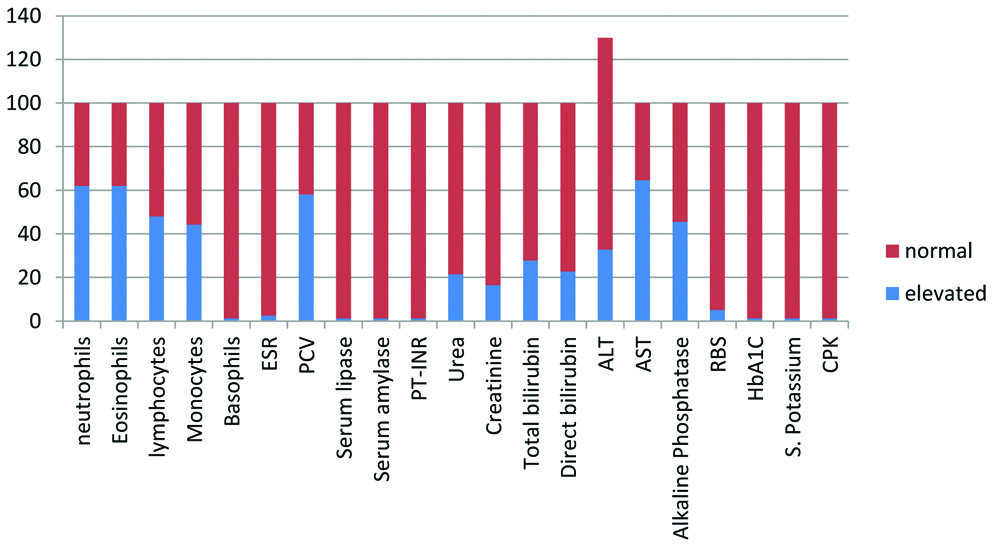

The distribution of laboratory parameters are shown in [Table/Fig-4]. The predominant parameters that were elevated were differential white blood cell counts and alkaline phosphatase levels. All the participants received doxycycline either alone (96.2%) or in combination with ceftriaxone or azithromycin. Majority of the participants were discharged within 6 days (48%), with a mean duration of hospitalisation of 5.6 days while 27.9% of the patients had complications. While most common complication was gastrointestinal (18.1%), multiorgan involvement was present in 11.4% of the participants [Table/Fig-5]. The mean values of various laboratory parameters estimated are given in [Table/Fig-6].

Distribution of laboratory parameters.

| Characteristic | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|

| Antibiotic used |

| Cephotriaxone and doxycycline | 1 | 1.3 |

| Doxycycline and azithromycin | 2 | 2.5 |

| Doxycycline | 76 | 96.2 |

| Duration of hospitalisation (in days) |

| >6 | 31 | 39.2 |

| <6 | 48 | 60.8 |

| Complication |

| Yes | 22 | 27.9 |

| No | 57 | 72.1 |

| Types of complications (n=22) |

| Gastrointestinal | 4 | 18.1 |

| Neuropsychiatric | 1 | 4.5 |

| Neuropsychiatric; electrolyte imbalance | 1 | 4.5 |

| Neurological | 1 | 4.5 |

| Gastrointestinal; haematological | 2 | 9.1 |

| Renal | 3 | 13.6 |

| Respiratory | 2 | 9.6 |

| Obstetric | 1 | 4.5 |

| Gastrointestinal; renal | 1 | 4.5 |

| Electrolyte imbalance | 1 | 4.5 |

| Renal; respiratory | 1 | 4.5 |

| Haematological; renal | 1 | 4.5 |

| Multi organ | 1 | 4.5 |

| Hepatic; renal | 2 | 9.1 |

| No of organs affected |

| Single | 13 | 16.4 |

| Multi organ | 9 | 11.4 |

| No | 57 | 72.2 |

Mean values of the parameters.

| Parameters | Mean | SD |

|---|

| Pulse (beats/minute) | 85.3 | 9.4 |

| Total count | 7679.70 | 3372.6 |

| Neutrophils | 70.7 | 8.4 |

| Lymphocytes | 25.8 | 10.1 |

| Eosinophils | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Monocytes | 2.4 | 1.4 |

| Platelet count (lacs/cumm) | 1.97 | 2.3 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.6 | 1.7 |

| PCV | 36.1 | 5.9 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 31.0 | 26.8 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| Total bilirubin | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| ALT | 63.4 | 56.3 |

| AST | 62.8 | 53.0 |

| ALP | 98.2 | 40.8 |

This study found a significant difference in the presence of CNS symptoms with respect to the age of the participants. Participants aged >40 years were more at risk of CNS symptoms (31.4%) compared to those aged <40 years (11.4%). The observed difference was statistically significant (p<0.05) [Table/Fig-7]. A significant difference in the total whole blood cell count was observed with respect to the sex of the participants. Females had increased risk of abnormal counts compared to males. The observed difference was statistically significant (p<0.05) [Table/Fig-8]. There was also a significant difference in the laboratory parameters pertaining to renal functions, with respect to the presence of multi-organ involvement. The observed difference was statistically significant (p<0.05) [Table/Fig-9]. However, there was no mortality among the study participants due to scrub typhus.

Association between demographic characteristics and significant symptoms.

| Parameters | CNS | N (79) | Chi square | p-value |

|---|

| Present | Absent |

|---|

| Age (years) |

| <40 | 5 (11.4) | 39 (88.6) | 44 | 4.8 | 0.02 |

| >40 | 11 (31.4) | 24 (68.6) | 35 |

Association between demographic parameters and laboratory findings.

| Parameters | Total count | N (79) | Chi square | p-value |

|---|

| Low | Normal | High |

|---|

| Sex |

| Female | 23 (74.2) | 1 (3.2) | 7 (22.6) | 31 | 7.3 | 0.02 |

| Male | 27 (56.3) | 13 (27.1) | 8 (16.7) | 48 |

Association between complication with multisystem involvement and clinical parameters.

| Factor | N=79 | Mean | SD | t-value | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|

| Urea | 9 | -0.396 | 0.527 | -2.877 | -0.670 to -0.122 | 0.005 |

| Creatinine | 8 | 1.375 | 0.517 | -3.720 | -0.762 to -0.230 | 0.0001 |

Discussion

In this study majority of the participants belonged to less than 40 years of age. Another predominant symptom observed in our study was headache and apart from these symptoms, abdominal symptoms were also present in 38% of the participants. In a study done by Jain D et al., the mean age of the participants was 38 years, similar to this study. Abdominal symptoms were present in 33% of the participants, similar to this study (38%) [5]. In another study done by Narvencar KPS et al., the abdominal symptoms were present in 46.7% of the participants [7]. Eschar was present in 16.4% of the study participants, similar to the study observed by Zhang L et al., [8]. In addition 17.7% of the participants had respiratory signs including bilateral crackles. Moreover, splenomegaly was also present in 12.7% of the participants. Studies have documented that presence of eschar is essential in determining the prognosis of patients with scrub typhus infections. Patients without eschar are proven for increased risk of severe complications. However, this correlation could not be explored in the index study due to paucity of information. Identification of preferences sites of eschar formation is also important in order to detect it early and address at earliest stages [9].

It is essential to document the incubation period and duration between onset of fever and the onset of other symptoms was clinically important. The incubation period is documented from time of bite by infected chiggers to appearance of fever. However, incubation period was not documented in the present study. In a study done by Takhar RP et al., three patients were diagnosed in the second week and had manifestation of fever and other manifestation of scrub typhus two weeks after the onset of fever [3]. However, several studies reported a variation in the presentation of eschar. Some Indian researchers like Vivekanandhan M et al., documented the prevalence of eschar to be around 45% [10]. It is worthwhile noting that the diagnosis made in the above study was using Weil-Felix reaction which does not have established validity. In the index study, we used rapid diagnostic test ICT which although is not a gold standard Test like immunofluorescent or Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) but is a good tool for rapid diagnosis [11].

Scrub typhus is predominantly said to result in multi organ dysfunction. With more participants having low leucocyte counts and significant prevalence of thrombocytopenia, 27.9% of participants had complications of which majority of the complications were related to gastro intestinal system including hepatomegaly and renal involvement. However, multiple organs were affected in 11.4% of the present study participants. In another study 48.5% of the participants had more than three organ systems involve while 30% of the participants had about five organ dysfunctions during the hospital stay [3]. This difference could be due to the aggressive management and early presentation to the health care facility in index study; however, there is a need for substantial evidence to support the difference. The common complications involve circulatory collapse, Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), haematological complications and electrolytes imbalances as seen in almost all participants in the study. Some studies have documented other extraneous complications including meningoencephalitis, gastrointestinal bleeding, acute renal failure, hearing impairment, opsoclonus and pancreatitis [3,12,13]. While most of the infections were easily controlled by doxycycline antibiotic, some of the patients required ceftriaxone and azithromycin combinations. Antimicrobial resistance was reported in several Asian countries like Thailand etc., [14]. Moreover, refractory cases have also been reported in other countries, with an emerging threat of drug resistance [15].

In this study, present athours found statistically significant relationship between the age of the participants and presence of CNS symptoms. There was an increase predisposition to CNS symptoms including lethargy etc., among patients who were >40 years of age compared to those <40 years of age. Moreover, there was a variation in total count levels with respect to the gender of the participants. Females were more prone for an increased variation while males were found to have near normal total count levels. There are few studies which have correlated the age and organ specific complications for scrub typhus.

We did not report any mortality from scrub typhus due to the presence of early case management and adequate antibiotic coverage. The mortality rate from scrub typhus has been ranging from 7-30% [16] all over the world with about 30% in Taiwan [17] and 10% in Korea [18]. In India studies done by Takhar RP et al., documented mortality rate of 21.2% [3]. It was higher compared to studies done by Mahajan SK et al., with the mortality of 14.2% and Kumar K et al., with the mortality of 17.2% [4,19]. The comparison with similar published studies is given in the [Table/Fig-10] [3,5,7,10,20-22].

Comparison of clinical and laboratory findings of the present study with published literature [3,5,7,10,20-22].

| Study | Clinical symptoms | Clinical signs | Laboratory investigation |

|---|

| Parameters | Percentage (%) | Parameters | Percentage (%) | Parameters | Percentage (%) |

|---|

| Present study | Fever | 49.4 | Eschar | 16.4 | Raised serum creatinine | 16.5 |

| Cough | 19 | Heptomegaly | 8.9 |

| Headache | 38 |

| Abdominal symptoms | 38 | Lymphadenopathy | 8.9 | Thrombocytopenia | 49.4 |

| Multiple organs affected | 11.4 |

| Girija S et al., [20] | Fever | 100 | Eschar | 4 | Elevated transaminases | 20 |

| Chills | 66 | Heptomegaly | 3 | Thrombocytopenia | 84 |

| Myalgia | 95 | Lymphadenopathy | 4 |

| Cough | 40 | Rash | 3 | Raised serum creatinine | 80 |

| Nausea | 28 |

| Inamdar S et al., [21] | Fever | 79.5 | Eschar | 75.5 | - | - |

| Headache | 97 | Hepatomegaly | 74 |

| Abdominal pain | 56 | Lymphadenopathy | 52.5 |

| Anorexia | 54.5 |

| Varghese GM et al., [22] | Fever | 100 | Eschar | 55 | Elevated transaminases | 72.5 |

| Myalgia | 32.4 | Hyperbilirubinaemia | 26.6 |

| Headache | 42.8 |

| Cough | 37 | Rash | 1.2 |

| Altered sensorium | 24.6 | Raised serum creatinine | 12.9 |

| Seizures | 6.5 |

| Vivekanandan M et al., [10] | Fever | 100 | Eschar | 46 | Elevated transaminases | 95.9 |

| Myalgia | 38 | Hepatomegaly | 28 | Thrombocytopenia | 28 |

| Headache | 52 | Lymphadenopathy | 80 | Hyperalbuminea | 87.5 |

| Nausea | 58 | Rash | 14 | Hyperbilirubinaemia | 20.5 |

| Cough | 40 | Altered sensorium | 20 | Raised serum creatinine | 13 |

| Jain D et al., [5] | Abdominal symptoms | 33 | Eschar | 12.82 | Thrombocytopenia | 46.2 |

| Splenomegaly | 51 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 20.5 |

| Narvencar KPS et al., [7] | Abdominal symptoms | 46.7 | Eschar | 13.3 | Raised serum creatinine | 33.3 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 26.7 | Thrombocytopenia | 40 |

| Takhar RP et al., [3] | Fever | 100 | Eschar | 12.1 | Mortality rate | 21.2 |

| Cough | 48.5 | Lymphadenopathy | 18.2 | Raised creatinine | 51.5 |

| Myalgia | 30.3 |

| Multiple organ dysfunction | 48 |

Limitation(s)

Being a retrospective study the active burden of the infection in the population could not be ascertained. A long term follow-up study on large sample is required to analyse the clinical extent of involvement of the disease in order to devise preventive strategies.

Conclusion(s)

Scrub typhus is a common infection of the tropics and is often labelled as pyrexia of unknown origin. This study has documented the presence of significant correlation between age of the participants and clinical presentation of symptoms of central nervous system. This study also elucidated a significant association between age at presentation and symptoms of central nervous system. It is therefore essential to note that the index of suspicion should be high for scrub typhus fever when the patient presents with fever, thrombocytopenia and multi organ involvement in order to prevent mortality.

*the figures will not total to 100

*one or more of abnormal urine analysis including proteinuria, glucosuria, presence of pus cells, red blood cells