HBV and HCV are diseases characterised by a high global prevalence with complex clinical course, and limited effectiveness of currently available antiviral therapy. HBV and HCV are serious public health problems worldwide and major causes of chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [1].

Chronic viral hepatitis due to HBV and HCV are of major global significance due to both their prevalence and the associated morbidity and mortality. More than 350 million people worldwide have chronic HBV, out of some 2 billion exposed, leading to more than 6,00,000 deaths per year; 170 million have chronic HCV, with almost 5,00,000 deaths per year [2].

WHO SEAR (South-East Asia Regional) countries have around 30% of viral hepatitis burden, with estimated 100 million and 30 million people infected with HBV and HCV, respectively. India represented high endemicity category for HBsAg having population prevalence of 3-4% for chronic HBV infection with prevalence of around 1% for chronic HCV infection [3]. The age of acquisition of HBV is an important determinant of outcome; the earlier the age, the higher the risk of chronicity (e.g., >90% in new-borns (vertical transmission), 30% in children aged 2-5 years and <5% in adults) [4] and in case of HCV, the prevalence progressively increases with increase in the age [5-7].

Clinically, HBV infection is indistinguishable from other viral hepatitis. As a result, its diagnosis relies on a specific lab tests for distinguishing it from other viral hepatitis. Several viral markers are available for the detection of HBV and HBsAg is the major viral marker used for the detection of HBV infection. HBsAg is the first marker to appear and becomes detectable during acute HBV infection [1,8-12].

A significant percentage of individuals suffering from HCV infection are asymptomatic and are detected only on random check-ups for various purposes. The presence of hepatitis C antibody in the serum or plasma is an indication of HCV infection, although this does not indicate whether the infection is acute, chronic or resolved [1,13].

The various methods available for the detection of HBsAg are enzyme immunoassays, radioimmuno assays, immunochromatographic assays and haemagglutination assays. Among these methods the most sensitive methods are enzyme immunoassays and radioimmuno assays, the former method is generally used by reference laboratories because of its accuracy, low cost and safety when compared with later methods [1,11,12].

One of the main steps in the management of HBV infection is prevention by using vaccination. A cost-effective study concluded that the addition of hepatitis B vaccine in to the national immunisation program of India will lead to reduction in the carrier rate (from 4.0% to 1.15%). As a pilot project in the year 2003, hepatitis B vaccine was introduced into few districts and cities. Subsequent to this success, the project was further introduced into 10 other states. In the year 2005, hepatitis B vaccine was integrated in to National Rural Health Mission and thereafter in the year 2011 full country coverage was started [4]. At present, there is no vaccine available against HCV. But continuous research is going on for the development of the same using novel vaccine candidates such as recombinant protein, peptide and also vector-based vaccines, with some of them entering phase I/II clinical trials [5,14].

To know the magnitude of transmission of any disease in a community and for its control and prevention; trend and study of its prevalence is most important. The ideal sample for any seroprevalence study is from the general population. However, this being not always feasible, prevalence among blood donors is commonly used. As the blood donor population is usually made up of young and apparently healthy adults, such a study is not able to estimate the prevalence in the children and the elderly (sampling bias).

Though there are studies about these virus infections from our region, most of them are from blood bank [15,16] and as mentioned above there will always be a selection and age bias and at the same time clinically suspected cases will be excluded. Hence, this hospital based study was conducted to analyse the overall trend of hepatitis B and C infection and to estimate the seroprevalence in a tertiary care hospital of Southern India.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective study conducted at the Department of Microbiology, Sri Venkateswara Institute of Medical Sciences (SVIMS), Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh, India. Institute Ethics committee approval was obtained for this study (IEC no. 708/12.02.2018). Implied consent was obtained while collecting the blood sample. The blood samples from inpatients and outpatients of various Departments who were advised for HBsAg test and HCV antibody test as part of routine preoperative screening and/or for diagnostic purposes were included in the study. The data for the aforementioned tests for a period of three years four months (from September 2013 to December 2016) was retrieved from Departmental registers and Hospital Information System. Data analysis was done from 15.02.2018 to 15.05.2018. Blood collected in the test tubes was allowed to clot at room temperature and then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes to obtain serum [17].

The serum was tested for HBsAg and anti-Hepatitis C antibody using Hepalisa and Microlisa ELISA kit (both kits from J. Mitra & Co, Pvt., Ltd., New Delhi, India) respectively. The sensitivity and specificity of the former kit is 100% while that of the later kit is 100% and 97.4%, respectively. All the tests were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Patients age in years was divided into 4 groups viz., group 1, 2, 3 and 4 where in group 1 comprises of ≤18 years/paediatric patients, group 2- 19-40 years/adult, group 3- 41-59 years/middle age and group 4- ≥60 years/geriatric patients. This study includes patients from all age groups. As most of the studies excluded children and elderly age groups, therefore, the impact of viruses in these age groups were also studied which is one of the assets.

Statistical Analysis

Data were recorded using Microsoft Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) on a predesigned proforma. Statistical software IBM SPSS, Version 20.0 (IBM SPSS Statistic, Somers NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The seroprevalence was obtained after calculating total number of positive and negative cases. Normally distributed variables were summarised by Mean and Standard Deviation; remaining variables were summarised as median {Interquartile Range (IQR)}. All categorical variables were summarised as percentages.

Results

A total of 77,158 samples were tested for HBsAg whereas 58,024 were tested for the presence of anti-HCV antibody during September 2013 to December 2016.

Out of 77,158 samples tested, 1753 samples were positive for HBsAg with the seroprevalence of 2.27%. Seroprevalence of HBV was maximum in the age group 3 (41-59 years/middle age) followed by age group 4, 2 and 1. Year wise and age wise distribution of HBV is shown in [Table/Fig-1].

Year wise and age wise distribution of HBV.

| Age group* | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Total positives | Mean±SD |

|---|

| Total | Positive (%) | Total | Positive | Total | Positive | Total | Positive |

|---|

| 1 | 270 | 0 (0) | 860 | 5 (0.58) | 832 | 6 (0.72) | 953 | 3 (0.31) | 14 | 16.42±1.42 |

| 2 | 1541 | 47 (3.04) | 5294 | 146 (2.75) | 4974 | 145 (2.91) | 6081 | 115 (51.3) | 453 | 32.40±5.93 |

| 3 | 2932 | 79 (2.69) | 9726 | 281 (2.88) | 9441 | 248 (2.62) | 10719 | 224 (2.08) | 832 | 50.22±5.19 |

| 4 | 2032 | 28 (1.37) | 6640 | 128 (1.92) | 6498 | 132 (2.03) | 8365 | 166 (1.98) | 454 | 67.05±5.98 |

| Total | 6775 | 154 (2.27) | 22520 | 560 (2.48) | 21745 | 531 (2.44) | 26118 | 508 (1.94) | 1753 | |

*group 1: ≤18 years/paediatric; group 2: 19-40 years/adult; group 3: 41-59 years/middle age; group 4: ≥60 years/geriatric

A total number of 58,024 samples were tested for HCV of which 426 samples turned out to be positive for anti-HCV antibodies, hence the seroprevalence was 0.73%. Seroprevalence of HCV was maximum in the age group 3 (41-59 years/middle age) followed by age group 4, 2 and 1. Year wise and age wise distribution of HCV is depicted in [Table/Fig-2].

Year wise and age wise distribution of HCV.

| Age group* | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Total positives | Mean±SD |

|---|

| Total | Positive | Total | Positive | Total | Positive | Total | Positive |

|---|

| 1 | 187 | 2 | 691 | 0 | 669 | 3 | 844 | 0 | 5 | 17.2±0.83 |

| 2 | 1133 | 4 | 4333 | 22 | 4127 | 18 | 5201 | 19 | 63 | 33.28±6.35 |

| 3 | 1856 | 23 | 7008 | 63 | 4616 | 39 | 8351 | 67 | 192 | 50.49±5.24 |

| 4 | 1135 | 14 | 4579 | 33 | 6914 | 67 | 6380 | 52 | 166 | 67.30±5.58 |

| Total | 4311 | 43 | 16611 | 118 | 16326 | 127 | 20776 | 138 | 426 | |

*group 1: ≤18 years/paediatric; group 2: 19-40 years/adult; group 3: 41-59 years/middle age; group 4: ≥60 years/geriatric

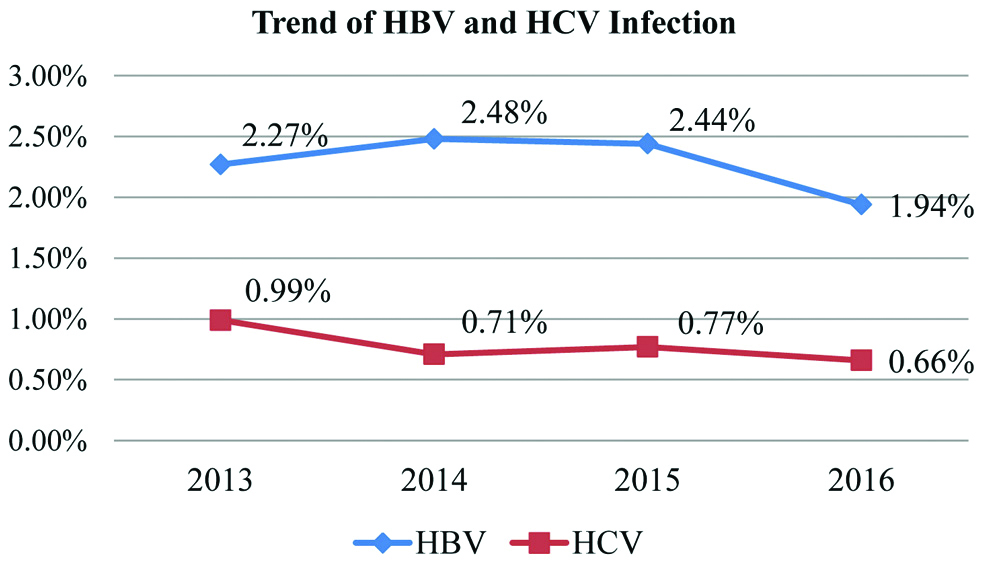

It was observed that the seroprevalence for both HBV and HCV viruses was maximum in the same age group (41-59 years/middle age). A gradual decrease in the HBV prevalence was observed. However, HCV infection showed a rather fluctuating trend. Trend of HBV and HCV infection over the years is shown in the [Table/Fig-3].

Trend of HBV and HCV infection.

Male predominance was observed for both hepatitis B and hepatitis C positivity for all the years. Year wise and Gender wise distribution of HBV and HCV is given in [Table/Fig-4,5], respectively. Overall gender wise distribution of HBV and HCV is presented in [Table/Fig-6].

Year wise and gender wise distribution of HBV.

| Year | Female | Male |

|---|

| Total | Positive | Total | Positive |

|---|

| 2013 | 2672 | 51 (1.9%) | 4103 | 103 (2.51%) |

| 2014 | 8978 | 138 (1.53%) | 13542 | 422 (3.11%) |

| 2015 | 8604 | 124 (1.44%) | 13141 | 407 (3.09%) |

| 2016 | 10555 | 126 (1.19%) | 15563 | 382 (2.45%) |

| Total | 30809 | 439 (1.42%) | 46349 | 1314 (2.83%) |

Year wise and gender wise distribution of HCV.

| Year | Female | Male |

|---|

| Total | Positive | Total | Positive |

|---|

| 2013 | 1772 | 16 (0.90%) | 2539 | 27 (1.06%) |

| 2014 | 6781 | 41 (0.60%) | 9830 | 77 (0.78%) |

| 2015 | 6756 | 60 (0.88%) | 9570 | 67 (0.70%) |

| 2016 | 8685 | 41 (0.47%) | 12091 | 97 (0.80%) |

| Total | 23994 | 158 (0.66%) | 34030 | 268 (0.79%) |

Gender wise distribution of HBV and HCV.

| Age group* | Female | Male |

|---|

| HBV | HCV | HBV | HCV |

|---|

| Tested | Positive (%) | Tested | Positive (%) | Tested | Positive (%) | Tested | Positive (%) |

|---|

| 1 | 1291 | 2 (0.15) | 1033 | 4 (0.39) | 1624 | 12 (0.74) | 1358 | 1 (0.07) |

| 2 | 8013 | 124 (1.55) | 6582 | 29 (0.44) | 9877 | 329 (3.33) | 8212 | 34 (0.41) |

| 3 | 13245 | 216 (1.63) | 10439 | 87 (0.83) | 19573 | 616 (3.15) | 13690 | 133 (0.97) |

| 4 | 8260 | 97 (1.17) | 5940 | 38 (0.64) | 15275 | 357 (2.34) | 10770 | 100 (0.93) |

| Total | 30809 | 439 (1.42) | 23994 | 158 (0.66) | 46349 | 1314 (2.83) | 34030 | 268 (0.79) |

*group 1: ≤18 years/paediatric; group 2: 19-40 years/adult; group 3: 41-59 years/middle age; group 4: ≥60 years/geriatric

Discussion

HBV and HCV virus infections are characterised by a high global prevalence with complex clinical course, and limited effectiveness of currently available antiviral therapy. These viral infections are of serious public health problems worldwide and major causes of chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [1,18].

According to the estimation by WHO, there are around 2 billion people having serological evidence of past or present HBV infections. More than 350 million are chronic carriers of HBV. Prevalence of HBV is 2-8% with 40 million carriers [1,19]. Hepatitis B prevalence changes from one country to another depending on the multiple factors such as behavioural, environmental, and host factors. There is a wide variation in the prevalence of HBsAg from one region to another in India. The highest prevalence has been reported from the tribes of Andaman and also from Arunachal Pradesh [1,20]. The global prevalence of HCV infection as per WHO estimate is around 2%. A 170 million persons are chronically infected due to this virus and 3-4 million people get newly infected every year [1,21].

In the present study, seroprevalence of HBV was 2.27% which corresponds to intermediate endemicity. The comparative studies for the same are tabulated in [Table/Fig-7] [1,2,6,7,16,22-30]. Seroprevalence of HCV in the present study was 0.73%. The comparative studies for the same are tabulated in [Table/Fig-8].

Comparative studies for seroprevalence of HBV [1,2,6,7,16,22-30].

| Seroprevalence of HBV |

|---|

| Sl. No. | Author | Year of publication | State/Country of study | Study population | Seroprevalence | Concordant/Discordant with present study |

|---|

| 1 | Chowdhury A et al., [6] | 2003 | West bengal | Community based | 2.97% | Concordant |

| 2 | Farooqi JI et al., [22] | 2007 | NWFP, Pakistan | Community based | 2.28% | Concordant |

| 3 | Sinha SK et al., [23] | 2012 | Eastern India | Blood donors | 2.27% | Concordant |

| 4 | Viet L et al., [24] | 2012 | Vietnam | Blood donors | 11.40% | Discordant |

| 5 | Antony J et al., [25] | 2014 | Kerala | Hospital based | 6.35% | Concordant |

| 6 | Yashovardhan A et al., [16] | 2015 | Andhra Pradesh | Blood donors | 2.20% | Concordant |

| 7 | Kateera F et al., [2] | 2015 | Rwanda, Africa | Health care workers | 2.90% | Concordant |

| 8 | Molla S et al., [26] | 2015 | Ethiopia | Pregnant woman | 4.40% | Concordant |

| 9 | Tripathi PC et al., [1] | 2015 | Telangana | Hospital based | 1.69% | Discordant |

| 10 | Rawat A et al.. [27] | 2017 | Delhi | Blood donors | 1.61% | Discordant |

| 11 | Baitha B et al., [28] | 2017 | Jamshedpur | Blood donors | 1% | Discordant |

| 12 | Ray K et al., [29] | 2018 | West Bengal | Blood donors | 1.36% | Discordant |

| 13 | Khan AA, [7] | 2018 | Telangana | Hospital based | 44.94% | Discordant |

| 14 | Mukherjee G et al., [30] | 2019 | West Bengal | Blood donors | 1.28% | Discordant |

Comparative studies for seroprevalence of HCV [2,6,7,15,22-30].

| Seroprevalence of HCV |

|---|

| Sl. No. | Author | Year of publication | State/Country of study | Study population | Seroprevalence | Concordant/Discordant with present study |

|---|

| 1 | Chowdhury A et al., [6] | 2003 | West bengal | Community based | 0.87% | Concordant |

| 2 | Farooqi JI et al., [22] | 2007 | NWFP, Pakistan | Community based | 4.06% | Discordant |

| 3 | Sinha SK et al., [23] | 2012 | Eastern India | Blood donors | 1.62% | Concordant |

| 4 | Viet L et al., [24] | 2012 | Vietnam | Blood donors | 0.17% | Concordant |

| 5 | Antony J et al., [25] | 2014 | Kerala | Hospital based | 0.85% | Concordant |

| 6 | Kateera F et al., [2] | 2015 | Rwanda, Africa | Health care workers | 1.30% | Concordant |

| 7 | Molla S et al., [26] | 2015 | Ethiopia | Pregnant woman | 0.26% | Concordant |

| 8 | Suresh B et al., [15] | 2016 | Andhra Pradesh | Blood donors | 0.56% | Concordant |

| 9 | Rawat A et al., [27] | 2017 | Delhi | Blood donors | 0.73% | Concordant |

| 10 | Baitha B et al., [28] | 2017 | Jamshedpur | Blood donors | 0.28% | Concordant |

| 11 | Ray K et al., [29] | 2018 | West Bengal | Blood donors | 0.83% | Concordant |

| 12 | Khan AA, [7] | 2018 | Telangana | Hospital based | 9.78% | Discordant |

| 13 | Mukherjee G et al., [30] | 2019 | West Bengal | Blood donors | 0.50% | Concordant |

Trend of HBV and HCV infection over the years is represented in the [Table/Fig-3]. There was a gradual decrease in the HBV prevalence over the years. Similar results were also reported by Baitha B et al., Ray K et al., Ahmed W et al., [28,29,31]. But studies by Arora I et al., reported an increased trend [32] and Mukherjee G et al., reported no change in the HBV trend [30].

HCV infection showed a rather fluctuating trend over the years. Similar trend was also reported by Ray K et al., and Sajjadi SM et al., [29,33]. On contrary, Pahuja S et al., Shaiji PS et al., [34,35] and Baitha B et al., reported a decreasing trend whereas Arora I et al., and Masood Z et al., observed an increasing trend [28,32,36].

As mentioned above, there is a wide variation in the prevalence and trend of hepatitis B and C infections which may be due to host and environmental factors, cultural and behavioural practices of specific regions. Added to these, the different generations of ELISA kits used, its sensitivity and specificity, study population selected will have an impact on these variations. Promiscuous sexual practices, increasing trend of tattooing and sharing of needles among drug users and absence of an effective vaccination for HCV are other reasons for its prevalence.

One of the important reason for the decreasing trend of HBV may be due to availability of effective vaccine. HBV immunisation in newborn persuade more than 95% of seroconversion and remarkably lowers infection frequency having zero incidence of chronic infection as compare to those who were not immunised. A retrospective study by Aggarwal R et al., in 2010-2011, in five districts of Andhra Pradesh state, where childhood HBV immunisation began in 2003, among 5-11-year-old rural children compared markers of HBV infection in HBV vaccinated children who were born in 2003/2004 (n=2674) and HBV unvaccinated children born in 2001/2002 (n=2350) [37]. Vaccinated children showed an increased rate of anti-HBs positivity, and a decreased rate of anti-HBc positivity, compared to the children who were unvaccinated.

Another study by Bhattacharya H et al., in two villages of Nicobar Islands evaluated the impact of the hepatitis B vaccination ten years after hepatitis B vaccination [38]. The total HBsAg positivity in Nicobarese tribe was decreased from 20.7% to 7.4% post ten years after getting vaccinated. There was considerable decrease in the HBsAg carrier rate among the vaccinated and non-vaccinated groups with reported 2.4% and 9.5% HBsAg positivity respectively. This change may be attributed to an increase in herd immunity and decrease in the source of infection which in turn were due to the effect of vaccination.

Su WJ et al., conducted a retrospective study to know the effect of universal infant HBV vaccination program on HBV carrier rate in pregnant women [39]. A 32 years period of cross-sectional data regarding maternal HBsAg and hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) screening program (launched in July 1984) was collected from the National Immunisation Information System. The annual HBsAg rate was decreased from 13.4% (for the year 1984-1985) to 5.9% (for the year 2016). Pregnant women who were vaccinated (born after July 1986) had the lowest relative risk of HBsAg positivity when compared with non-vaccinated pregnant women (born before June 1984).

Most common age affected due to HBV infection in the present study was age group 3 (41-59 years/middle age) with mean age affected being 50.22±5.19. Studies by Tripathi PC et al., (31-40 years) Khan AA et al., (21-40 years), Yashovardhan A et al., (21-30 years) Antony J et al., (20-39 years), and Singh NH et al., (21-30 years) [1,7,16,25,40] reported that the infection was common in lower age groups.

In the present study, HCV infection was highest in age group 3 (41-59 years/middle age) with mean age affected being 50.49 (±5.24). In a study by Tripathi PC et al., 41-50 years was most affected which was similar to this study [1]. Few studies also reported highest infection in younger age group such as Khan AA et al., (21-40 years) and Antony J et al., (20-39 years) [7,25]. The difference in most common age affected by HBV and HCV infection may be due to differences in study population and their age group classification, coverage of childhood vaccination for hepatitis B, unsafe sexual behaviour among drug users and tattooing in different populations.

In this study, male predominance was observed for both HBV and HCV infection.

In case of HBV distribution, gross difference was noted between the two genders. Similar results were also reported in studies by Khan AA et al., Yashovardhan A et al., Antony J et al., Singh NH et al., Sood S et al., [7,16,25,40,41]. But a marginal difference was reported by Tripathi PC et al., [1]. Though there was male predominance for HCV infection, the difference was only marginal. Tripathi PC et al., and Makroo RN et al., reported similar results as this study [1,42]. However, Antony J et al., reported female predominance in their study for HCV infection [25]. The reasons for the male predominance may be due to more chances of exposure of males to risk factors which were already mentioned.

Limitation

Present data is lacking important variables such as risk factors, epidemiological details, outcome of the patients. Though the observed results in present study reflect the patient population served by our hospital and may not exactly apply to the community but may reflect to some extent the seroprevalence in this part of the community because of the large number of cases investigated.

Conclusion

Prevalence of HBV and HCV in this study was 2.27% and 0.73%, respectively. HBV infection showed a decreasing trend and the HCV infection a fluctuating trend. As we all know that prevention is better than cure, attempt should be made to reduce the incidence of HBV and HCV by simple preventive measures like public education, screening of blood and blood products, increasing public awareness about importance of vaccination.

Future Recommendation

A prospective community based study among children, adults, pregnant women and high risk groups to know the exact seroprevalence in each group and to evaluate the long term benefits of hepatitis B vaccination can be planned as it is more than a decade since this vaccination has been introduced in this state.

*group 1: ≤18 years/paediatric; group 2: 19-40 years/adult; group 3: 41-59 years/middle age; group 4: ≥60 years/geriatric

*group 1: ≤18 years/paediatric; group 2: 19-40 years/adult; group 3: 41-59 years/middle age; group 4: ≥60 years/geriatric

*group 1: ≤18 years/paediatric; group 2: 19-40 years/adult; group 3: 41-59 years/middle age; group 4: ≥60 years/geriatric