Hepatic Tuberculous Abscess with Extension into Anterior Abdominal Wall

Sanjay M Khaladkar1, Radhika K Jaipuria2, Ronak Savani3, Shibani Saluja4

1 Professor, Department of Radio-diagnosis, Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College and Research Centre, Dr. D. Y. Patil Vidyapeeth, Pimpri, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

2 Resident, Department of Radio-diagnosis, Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College and Research Centre, Dr. D. Y. Patil Vidyapeeth, Pimpri, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

3 Postgraduate Resident, Department of Radio-diagnosis, Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College and Research Centre, Dr. D. Y. Patil Vidyapeeth, Pimpri, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

4 Postgraduate Resident, Department of Radio-diagnosis, Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College and Research Centre, Dr. D. Y. Patil Vidyapeeth, Pimpri, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr. Sanjay M Khaladkar, Flat No. 5, Plot 8, Tejas Bldg, Sahawas Society, Karvenagar, Pimpri, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

E-mail: drsanjaymkhaladkar@gmail.com

Hepatic Tuberculosis (TB) is rare form of extrapulmonary TB. Prevalence of primary tubercular abscess is 0.34% in hepatic TB. Isolated hepatic TB is rare with few reported sporadic cases. Primary hepatic tubercular abscesses rupturing into anterior abdominal wall is rare. The skeletal muscles are uncommonly affected by TB and are less preferred site for multiplication and survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis due to abundant blood supply, lack of lymphatic and reticulo-endothelial tissue in muscles and high lactic acid content. We report a case of 36-year-old patient who presented with lump in anterior abdominal wall in right hypochondriac region since one month. On ultrasound and CT study, he was detected to have hepatic abscess in right lobe with extension to overlying anterior abdominal wall. TB-PCR showed Mycobacterium complex. Genprobe test was positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Patient improved after Antikoch’s Treatment (AKT) with regression in hepatic and abdominal wall abscesses.

Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis, Glisson’s capsule, Macronodular tuberculosis, Sinus tract, Sub-capsular

Case Report

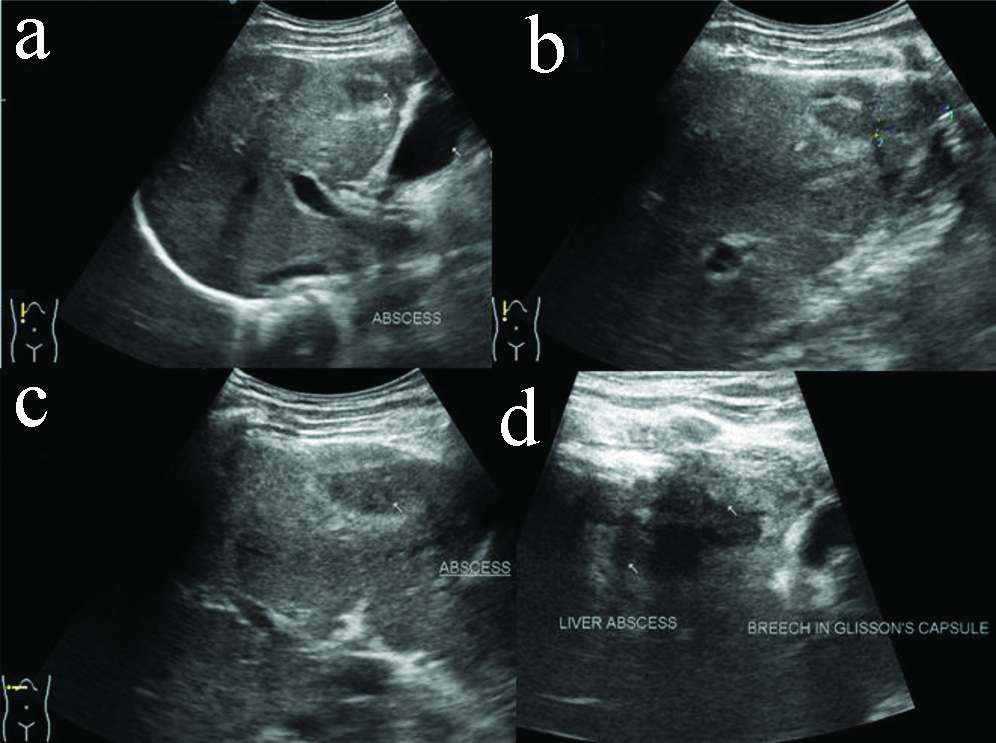

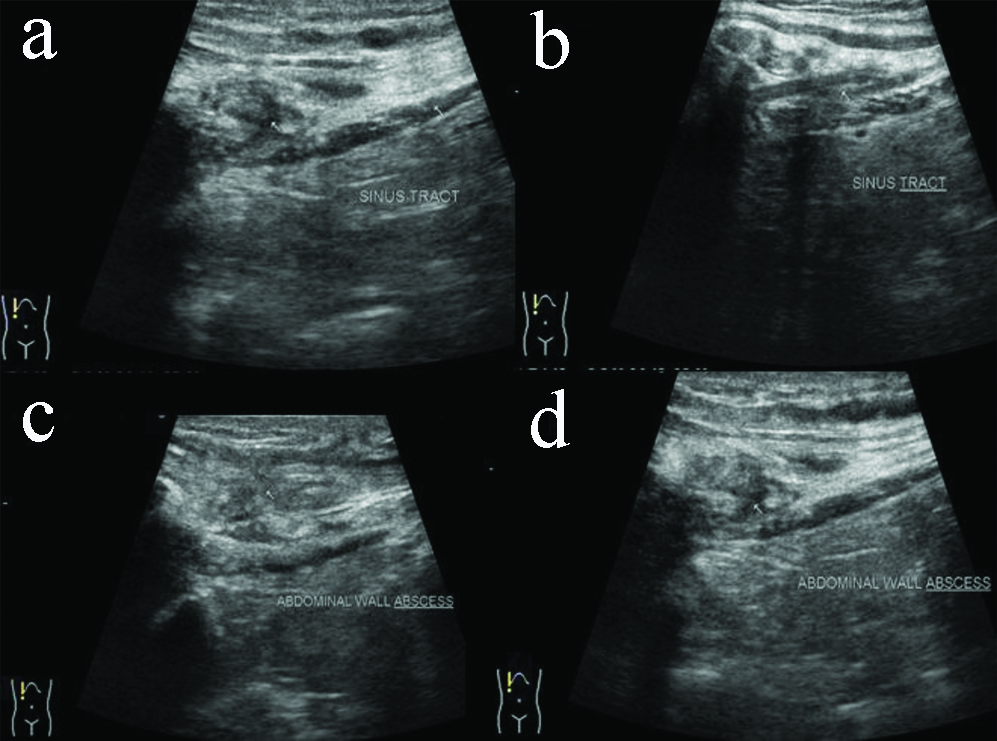

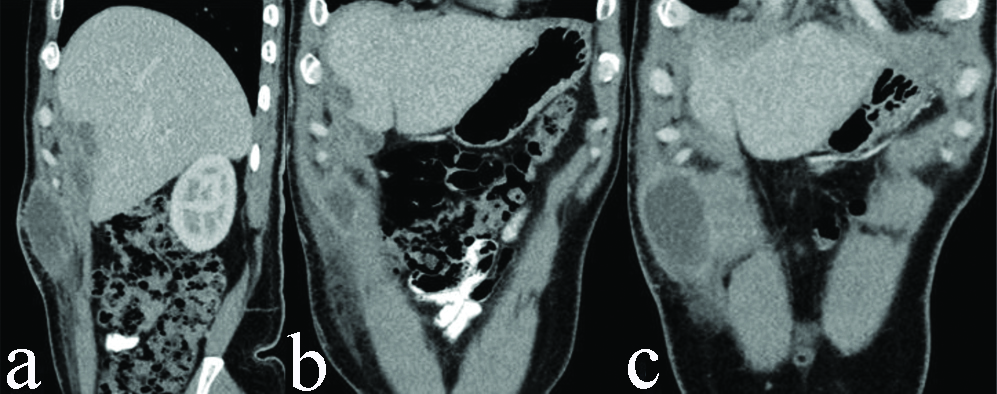

A 36-year-old male presented with lump in anterior abdominal wall with dull aching non-radiating pain in right hypochondriac region since one month. There was no history of fever, cough with expectoration, breathlessness, haemoptysis and weight loss. Serum bilirubin was 0.24 mg/dL, SGPT was 11 U/l, SGOT was 20 U/l, ALP was 63 U/l, blood urea and serum creatinine was normal. Sputum AFB was negative and showed occasional gram positive cocci. TLC was 4200/cmm. Neutrophills were 62%, lymphocytes-24%. Ultrasound (USG) of abdomen showed a hypoechoic lesion of size approximately 9×16×31 mm in anterior portion of right hepatic lobe suggestive of abscess [Table/Fig-1a-d]. There was a break in adjoining echogenic Glisson’s capsule with subcapsular extension of hepatic abscess measuring approximately 28×15 mm [Table/Fig-1d]. These abscesses were predominantly unliquified. A linear hypoechoic sinus tract of length 12 mm and 2 mm width was noted extending from subcapsular abscess into overlying anterior abdominal wall [Table/Fig-2a,b]. Abdominal wall showed a well-defined hypoechoic abscess of size approximately 42×9 mm and was predominantly unliquified [Table/Fig-2c,d]. Adjoining subcutaneous fat appeared thickened and echogenic. Findings were suggestive of hepatic tubercular abscess with extension into overlying abdominal wall.

USG abdomen showing well defined hypoechoic abscess in anterior portion of right hepatic lobe (a-c); with extension through Glisson’s capsule to involve adjoining anterior abdominal wall (d).

USG abdomen showing extension of hepatic abscess through Glisson’s capsule via sinus tract (a,b); to involve overlying anterior abdominal wall (c,d).

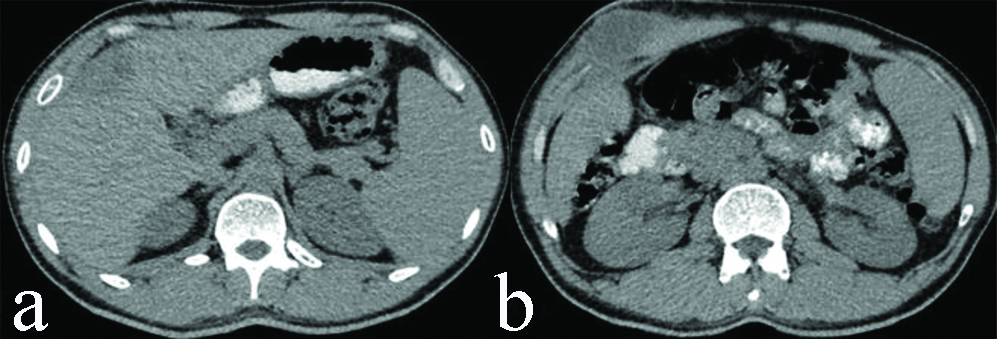

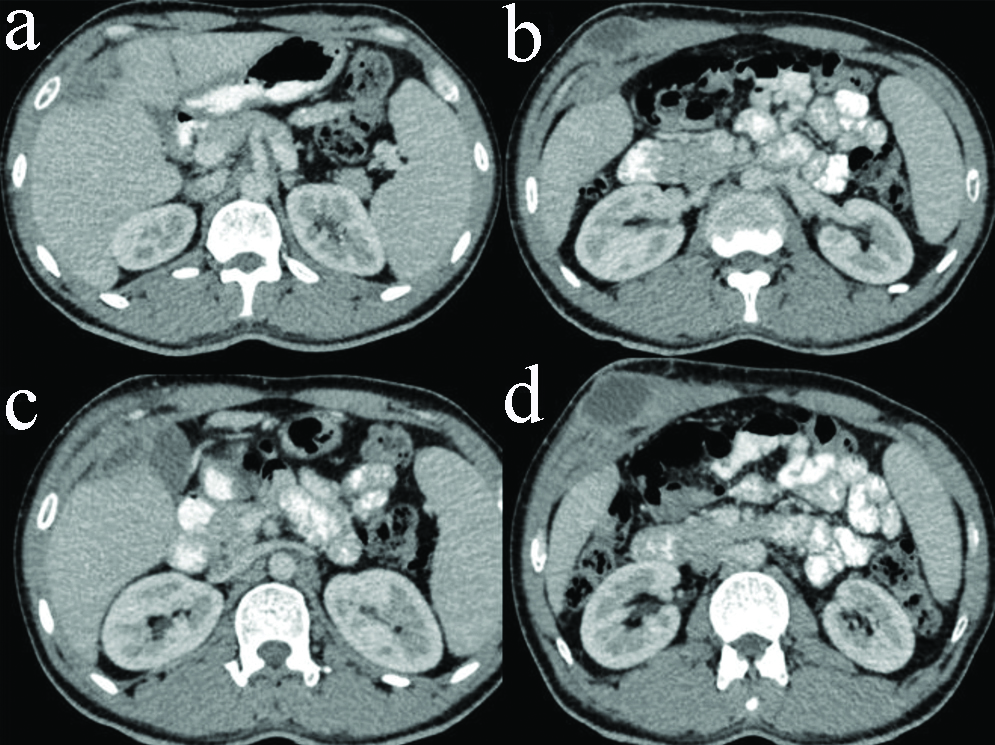

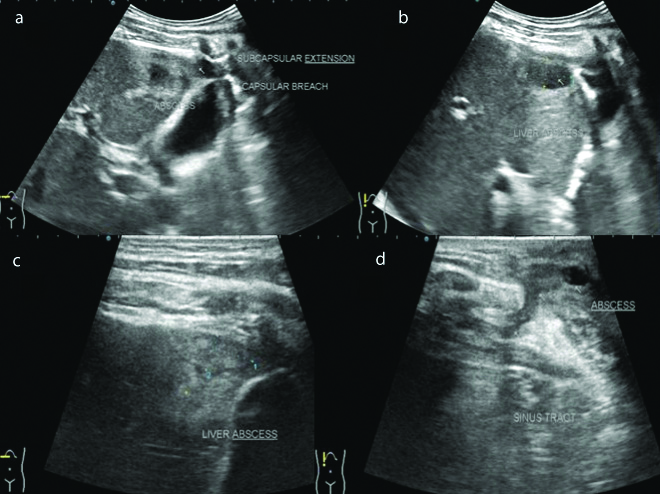

CT abdomen [Table/Fig-3,4 and 5] with contrast showed a hypodense lesion (CT value 20-30 HU) measuring approximately, 28 (Transverse) ×20 (Antero-posterior)×48 (Cranio-caudal) mm in peripheral portion of right hepatic lobe involving segment V with mild peripheral rim enhancement in contrast study. It was eroding through overlying capsule and extending in perihepatic space where it measured approximately 30×13 mm, showing mild peripheral post-contrast enhancement. From here it was extending to overlying abdominal wall muscle in right hypochondrium and measured approximately 49 (transverse)×32 (antero-posterior)×70 (Cranio-caudal) mm showing mild peripheral enhancement. Ill-defined soft tissue infiltrates were noted in adjoining subcutaneous fat planes. The abscess was pointing towards overlying skin. No retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy was noted.

Plain CT scan of abdomen showing well defined hypodense abscess in anterior portion of right hepatic lobe (a); with extension through Glisson’s capsule to involve adjoining anterior abdominal wall (b).

Contrast enhanced CT scan of abdomen showing well defined hypodense abscess in anterior portion of right hepatic lobe (a,b); with extension through Glisson’s capsule to involve adjoining anterior abdominal wall (c,d).

Contrast enhanced CT scan of abdomen showing well defined hypodense abscess in anterior portion of right hepatic lobe in sagittal (a); and coronal sections (b,c), with extension through Glisson’s capsule to involve adjoining anterior abdominal wall.

No AFB was detected in the abscess. TB-PCR showed Mycobacterium complex, sensitive to isoniazid and rifampicin. Genprobe test was positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex.

Patient was subjected to Antikoch’s treatment (AKT). Subsequent follow-up was done by USG which showed regression in hepatic and abdominal wall abscesses [Table/Fig-6].

Follow-up USG abdomen after 2 months showing mild regression of hepatic abscess in anterior portion of right hepatic lobe (a-c); with extension through Glisson’s capsule to involve adjoining anterior abdominal wall (d).

Discussion

Hepatic TB is rare form of extra-pulmonary TB. Usually it is associated with miliary TB or infective foci in the lung or GIT. Bestowe in 1858 described first case of tubercular liver abscess [1,2]. Prevalence of primary tubercular abscess is 0.34% in hepatic TB. Gastro-biliary and duodenal and broncho-biliary fistulas are complications secondary to tubercular liver abscess. Spinal and paraspinal TB tracking into abdominal wall are known. However, primary hepatic tubercular abscesses extending to anterior abdominal wall is rare with only two cases reported in the literature [3,4].

The skeletal muscles are rarely affected by TB even in patients with widespread involvement by the disease. They are not preferred site for multiplication and survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis [5,6]. Desai N et al., recorded 1 case of primary skeletal TB in over 8000 cases of all cases of TB with an incidence of 0.015%. Rare involvement of skeletal muscle is likely due to abundant blood supply, lack of lymphatic and reticulo-endothelial tissue in muscles and high lactic acid content [7].

Pandya JS et al., reported a case of tuberculous liver abscess involving segment V of right hepatic lobe with extension in overlying anterior abdominal wall. USG guided aspiration of liver abscess showed acid fast bacilli on smear. Growth of acid fast bacilli was noted at end of 10 days in Lowenstein Jenson medium. Patient responded well to AKT in six months [2]. Abe K et al., reported a case of tuberculous abscess involving peripheral portion of left hepatic lobe extending to involve overlying anterior abdominal wall in a 58-year-old diabetic patient [3]. The specimen showed features typical of TB in the form of multiple epitheloid cell granulomas with caseous necrosis and langhans multinucleated giant cells. Culture for AFB, ZN stain and PCR were negative. In our case, abscess was noted in segment V of right hepatic lobe. No AFB was detected in the abscess. TB-PCR showed Mycobacterium complex, sensitive to isoniazid and rifampicin. Genprobe test was positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Patient responded to antituberculous treatment and showed regression in hepatic abscess and anterior abdominal wall abscess during follow-up examinations.

Tubercular involvement of liver occurs as a part of disseminated disease. Hepatic parenchyma shows diffuse pattern of involvement with multiple small biliary nodules. Isolated hepatic TB is rare with few reported sporadic cases. Hepatic involvement in TB can be classified in 5 patterns: a) concomitant hepatic and pulmonary disease; b) Miliary TB; c) Primary hepatic TB (isolated); d) Tubercular hepatic abscess; e) Tubercular cholangitis [8]. Hepatic TB can also be classified based on pathology with radiological correlation in three forms: a) parenchyma type-micronodular and macronodular forms; b) serohepatic disease; c) tubercular cholangitis [8].

Hepatobiliary TB commonly affects patients in 11-15 years of age group with peak incidence in second decade with 2:1 male preponderance. Primary hepatic TB is common in 4-6th decade of life. The disease may remain silent and detected incidentally when evaluation is done for non-specific symptoms. It may present with abdominal pain, organomegaly and jaundice. Jaundice occurs due to extrahepatic biliary obstruction secondary to periportal lymphadenopathy.

Hepatic involvement by TB occurs commonly in miliary TB with concurrent involvement of spleen and other abdominal organs. Miliary hepatic lesions are less than 2 mm in size, multiple and randomly distributed in entire hepatic parenchyma. On ultrasonography, they can be hypo-echoic or iso-echoic with respect to liver parenchyma. On computed tomography, they are seen as hypodense multiple foci with low attenuation value of 30-40 HU with minimal peripheral enhancement on post-contrast study, mimicking metastases, lymphoma and other granulomatous diseases. They may heal with calcification.

Macronodular tuberculosis-hepatic lesions are more than 2 cm in size and manifest as single or multiple hepatic lesions. They are rare as compared to miliary variant and are difficult to differentiate from neoplastic and various other lesions. Lesions with caseation necrosis results in tubercular abscess which can be central or multifocal. Tubercular liver abscess can rupture and result in extrahepatic complications like perihepatic abscess and infective peritonitis [8].

Subserosal plane of liver is involved in seropositive TB which is a rare variant. The connective tissue beneath the fibrous Glisson’s capsule of liver from which it is inseparable is involved. Ultrasonography and CT show peripherally positioned lesions centred in subcapsular plane of liver. The thickened liver capsule and subcapsule overlying these lesions simulate a sugar coating.

Presence of caseating granuloma in liver biopsy specimen is histologically considered diagnostic of TB and demonstration of AFB on ZN staining is only positive in 0.35% cases. TB-PCR and BATEC-MGIT960 are highly sensitive diagnostic modality for TB and give accurate results in less time. These should be evaluated in patients with hepatic abscess and not responding to conventional treatment. Patients usually respond well to category I antitubercular treatment. Some authors opine percutaneous drainage of abscess cavity followed by instillation of antitubercular drugs into it [2,8].

Conclusion

Hepatic TB is rare form of extrapulmonary TB. Primary hepatic tubercular abscesses rupturing into anterior abdominal wall are extremely rare. Presence of underlying hepatic abscess must be sought for in the presence of anterior abdominal wall abscess in right hypochondriac region.

Financial or Other Competing Interests

None.

Patient permission was obtained for publication of this work.

[1]. Hassani KI, Ousadden A, Ankouz A, Mazaz K, Taleb KA, Isolated liver tuberculosis abscess in a patient without immunodeficiency: A case reportWorld J Hepatol 2010 2(9):354-57.10.4254/wjh.v2.i9.35421161020 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2]. Pandya JS, Kandekar RV, Tiwari AR, Kadam R, Adhikari DR, Primary liver abscess with anterior abdominal wall extension caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis complexJ Clin Diagn Res 2016 10(11):PD08-PD09.PMID: 28050433 PMCID: PMC5198386 [Google Scholar]

[3]. Abe K, Aizawa T, Maebayashi T, Nakayama H, Sugitani M, Sakaguchi M, Isolated tuberculosis liver abscess invading the abdominal wall report of a caseSurg Today 2011 41(5):741-44.10.1007/s00595-010-4333-x21533955 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[4]. Gupta G, Nijhawan S, Katiyar P, Mathur A, Primary tubercular liver abscess rupture leading to parietal wall abscess: A rare disease with a rare complicationJ Postgrad Med 2011 57(4):350-52.10.4103/0022-3859.9009522120872 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[5]. Sabat D, Kumar V, Primary tuberculous abscess of rectus femoris muscle: A case reportJ Infect Dev Ctries 2009 3(6):476-78.10.3855/jidc.42119762963 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[6]. Alawad AAM, Gismalla MD, Tuberculous abscess of the anterior abdominal wall: An unusual site of presentationGlobal J Med Clin Case Reports2(1):008-009.2015.10.17352/2455-5282.000017 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[7]. Desai N, Patil S, Thakur BS, Das HS, Manjunath SM, Sawant P, Abdominal wall abscess secondary to subcapsular tubercular liver abscessIndian J Gastroenterol 2003 22(5):190-91.PMID: 14658538 [Google Scholar]

[8]. Kakkar C, Polnaya AM, Koteshwara P, Smiti S, Rajagopal KV, Arora A, Hepatic tuberculosis: a multimodality imaging reviewInsights Imaging 2015 6(6):647-58.10.1007/s13244-015-0440-y26499189 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]