Cutaneous Plexiform Schwannoma of the Digit- A Case Report

Shankaran Rukmini Niveditha1, Venkatesh Kusuma2

1 Professor, Department of Pathology, Kempegowda Institute of Medical Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

2 Professor, Department of Pathology, Kempegowda Institute of Medical Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Shankaran Rukmini Niveditha, Banashankari 2nd Stage, Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

E-mail: srniveditha@gmail.com

A common mimicker of Plexiform Neurofibroma (PN), Plexiform Schwannoma (PS) can occur sporadically and in weak association with NF2. It is important to differentiate between the two, as recurrence and malignant potential are common with PN requiring extensive surgery and rigorous follow-up. Though light microscopic features of PN and PS overlap especially in small biopsies, IHC with S-100 would help. S-100 immunostaining is diffuse and strong in PS while weak and patchy in PN. A rare case of cutaneous PS in the right index finger of a nine-year-old boy where S-100 immunostaining helped to confirm the diagnosis is hereby reported.

Benign neural neoplasm, Plexiform, S-100

Case Report

A nine-year-old boy presented with history of recurrent swelling in the right index finger for past 2-3 years. Past history revealed, that a small swelling of 1×1.5 cm occurred in the same area, when he was five-year-old which was incompletely excised and reported as Neurofibroma histopathologically. From the initial occurrence to the presentation at our hospital, the swelling recurred twice and was operated upon. No other co-morbidity was observed and detailed family history was non-contributory. The patient did not exhibit any signs of NF2. On examination a 2.5×2×2 cm solitary swelling was seen in the dorsum of the right index finger in the region of middle phalanx extending to the distal phalanx. X-ray showed a soft tissue mass extending from the middle interphalangeal joint to the distal phalanx, however there was no underlying bony involvement.

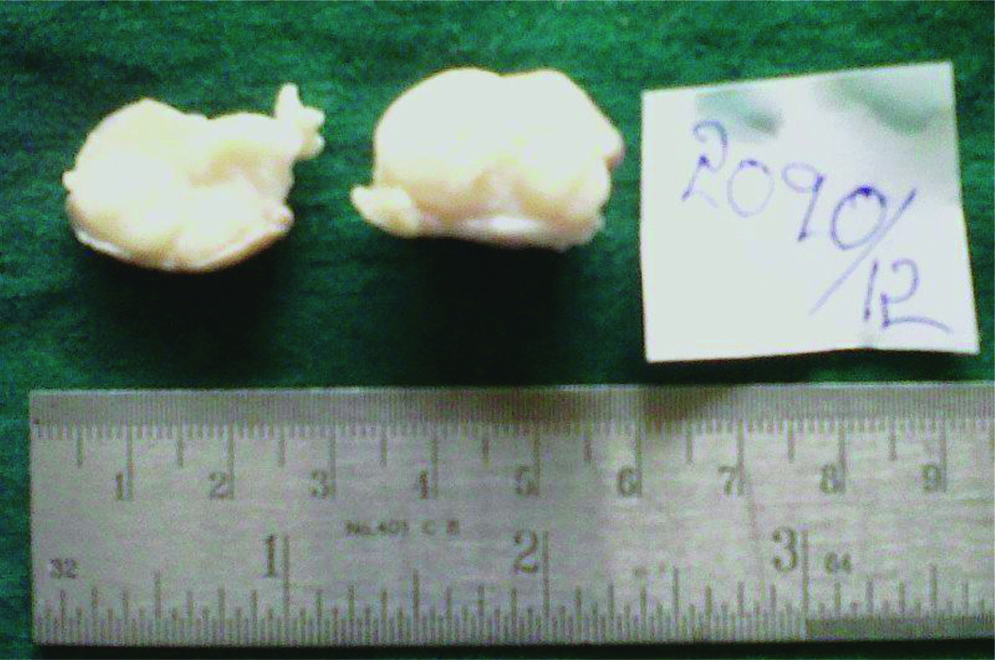

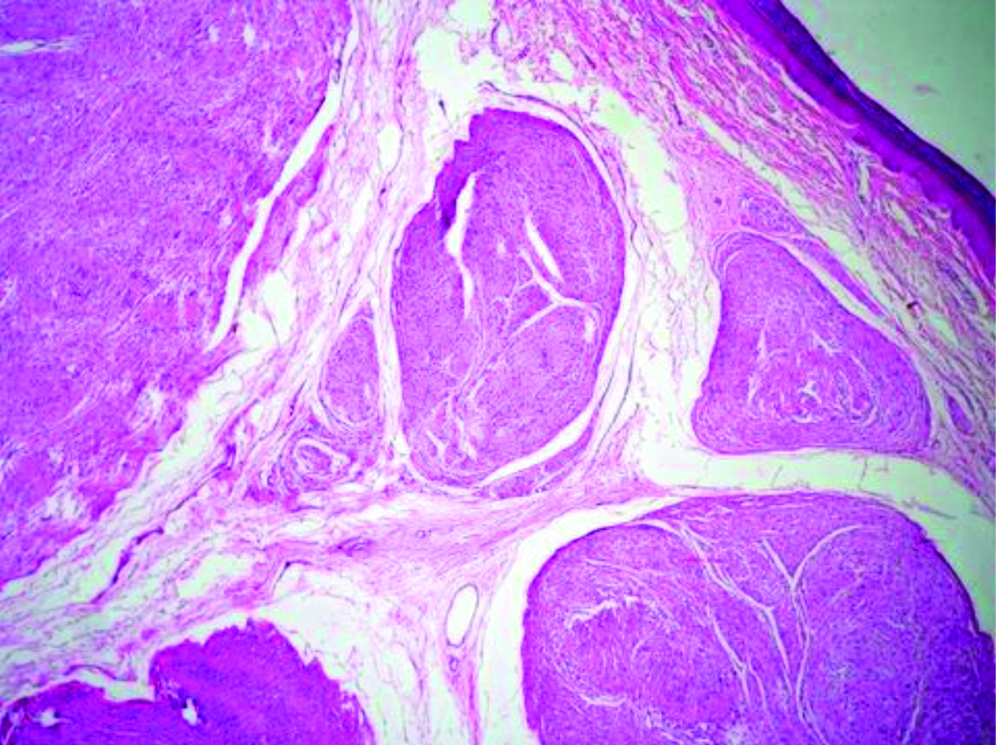

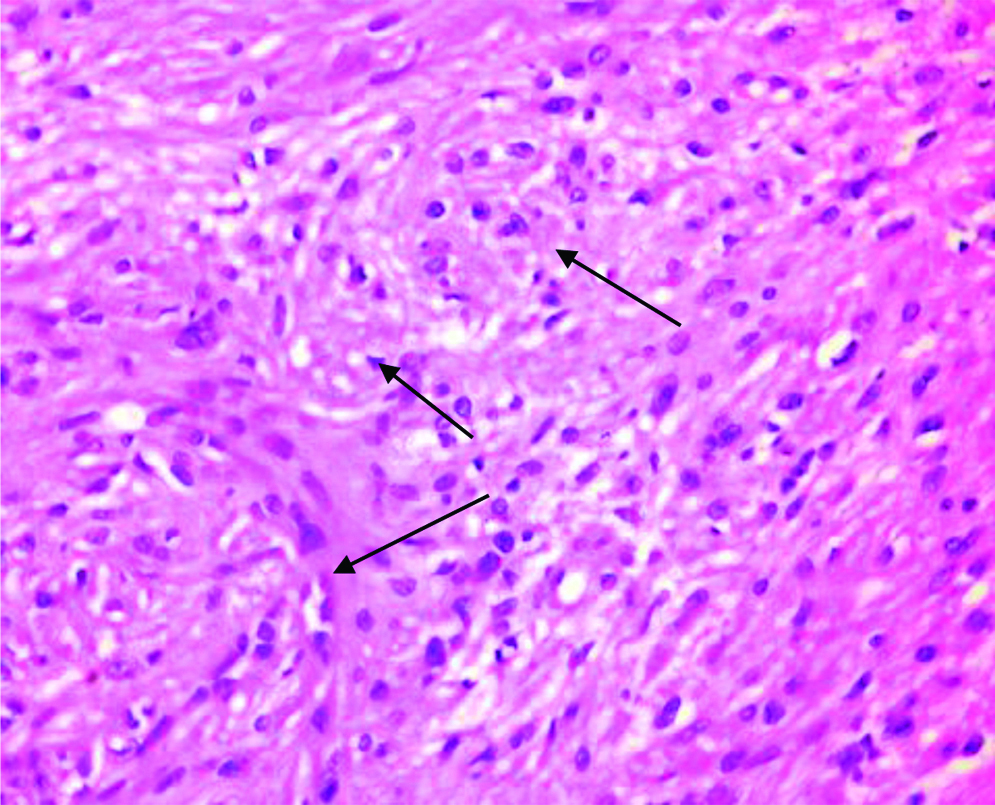

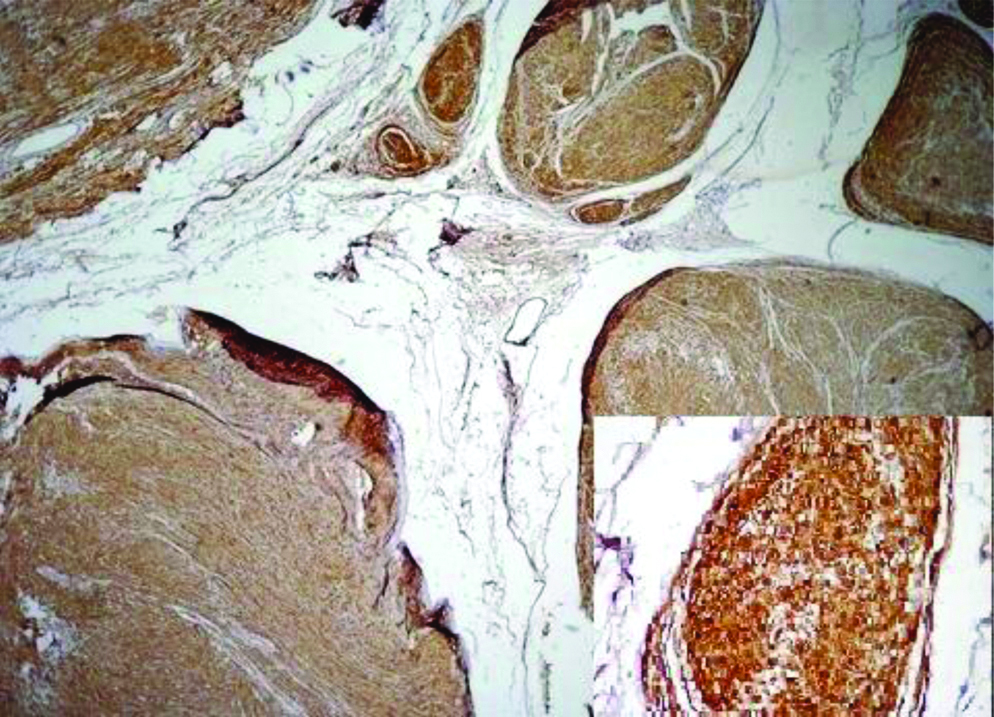

Preoperative FNAC was not done and excisional biopsy was performed. We received a single nodular, skin covered soft tissue mass measuring 2.5×1.5×1 cm. Cut section showed an encapsulated mass with lobulations [Table/Fig-1]. Microscopy revealed an encapsulated neoplasm in the dermis comprised of multiple nodules separated by fibrocollagenous stroma [Table/Fig-2]. Each of these nodules showed hypocellular and hypercellular areas with spindle cells having wavy nuclei [Table/Fig-3]. Hypocellular areas showed myxoid change separating the tumour cells. On extensive screening, an occasional Verocay body was seen. Adnexal structures were seen trapped in between. The deep surgical margin was free of tumour. A provisional diagnosis of Plexiform Schwannoma-right index finger, was given. Differential diagnosis of plexiform neurofibroma was considered along with cutaneous Leiomyoma. IHC for S-100 showed strong, diffuse cytoplasmic positivity in all the spindle cells throughout the neoplasm [Table/Fig-4], confirming the diagnosis of Plexiform Schwannoma, unlike the weak and patchy immunostaining of S-100 in PN. However more specific markers for Schwannoma like calretinin or CD 56, SMA and desmin to rule out leiomyoma could not be performed. As the tumour was enucleated in toto, and deep surgical margin was free of tumour, the patient was on follow-up for about 4 years following the surgery at our hospital and was doing well without any recurrence.

Gross specimen showing a well encapsulated neoplasm.

Histopathological section showing an encapsulated neoplasm in the dermis comprising of numerous nodules (H&E, 10x).

High power view showing spindle cells in whorls (arrows) (H&E, 40x).

Low power view showing diffuse cytoplasmic positivity of S-100 (Inset: 40x) (IHC, DAKO).

Discussion

Accounting for 5% of all schwannomas, PS was first described by Harkin and Reed in 1978, a rare benign tumour composed exclusively of Schwann cells exhibiting a plexiform growth pattern [1-3]. Plexiform refers to the serpentine distortion it imparts to the affected nerve segment, likened to “a bag of worms” [4]. Though a common mimicker of PN, PS can occur sporadically and in weak association with NF2 [5,6]. It is important to differentiate between the two, as recurrence and malignant potential are common with PN.

PS can be seen both in superficial and deep locations [6,7]. In the superficial location, 90% are cutaneous in skin and subcutaneous tissues. Among the deep seated locations, PS can occur in the deep somatic soft tissues of extremities, retroperitoneum, trunk, parotid, thoracic space and vulva [6,7]. Usually solitary, PS can be multiple in cases of Schwannomatosis [8].

Woodruff JM et al., reviewed six cases of congenital and childhood plexiform schwannomas. Of the six, one was congenital and none had features of NF1. Two thirds presented in infancy, with F:M ratio of 4:3. Tumour size ranged from 2 to 9 cm, two were well circumscribed while four had both circumscribed and infiltrative margins. All tumours had high cellularity, hyperchromasia and brisk proliferative activity making them prone to be misdiagnosed as Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumours (MPNST), but their nuclei were 3 times the size of NF nuclei and showed minimal variation. Mitoses ranged from 4-31/10 hpf. All the six cases showed diffuse S-100 positivity but were p53 negative. Surgical excision was done in all cases after a course of chemotherapy which failed to decrease the size. Recurrences were commonly seen in <1 year after initial excision which was termed as incomplete resection rather than recurrence [9]. Argenyi ZB et al., described a childhood plexiform tumour diffusely showing S-100 positivity and ultrastructural features of schwann cells and called it-“congenital neural hamartoma-fascicular schwannoma” [10].

PS differs from conventional cellular Schwannoma by its multinodularity, greater cellularity, increased proliferative activity and potential for infiltrative growth into surrounding tissues due to lack of encapsulation. Absence of well-defined capsule, degenerative changes and lymphoid collections were common features in PS [9]. Cellular schwannomas were more commonly seen in adults while PS was commonly observed in children. The proliferative activity of PS in childhood is attributed to factors such as rapid tissue growth in children. So called recurrence in many is because of incomplete resection, as clinicians avoid wide excision in young individuals, as seen in present case [9].

Malignant transformation is more common in PN than PS [6]. However a misdiagnosis is possible, especially in biopsy material from a cellular PS with hyperchromasia and increased mitosis which may be labelled as PN/MPNST. As seen in the case series of Woodruff JM et al, a five-month-old infant with pelvic PS was misdiagnosed as high grade sarcoma/intermediate grade MPNST, and planned for pelvic exenteration. There is a dramatic difference in the clinical outcome between benign and malignant tumours with MPNST having a grave prognosis and mortality rates ranging from 63%-68% [11]. IHC would be of use in, biopsy material of such cases. Focal scattered S-100 positivity and neurofilament positivity in tumour nodules would favour PN while diffuse strong S-100 cytoplasmic positivity and neurofilament staining limited to subcapsular area, may favour PS. Posner MA et al., also suggested that absence of nerve fibres demonstrated by sliver impregnation stains suggests PS [12]. Cytogenetic abnormalities like trisomy 17,18 have been reported in PS [13]. Multiple PSs are commonly associated with NF2 [13]. Some of the differences between PS and PN are tabulated in [Table/Fig-5].

Differences between PN and PS.

| Plexiform Neurofibroma (PN) | Plexiform Schwannoma (PS) |

|---|

| Strongly associated with NF1 | Weakly associated with NF1 and NF2 |

| Rarely solitary, usually affects large segments of nerves | Usually solitary, partially or completely encapsulated |

| Nuceli smaller, with nuclear atypia. | Nuclei 3-4 times size of neurofibroma nuclei with minimal pleomorphism |

| Silver impregnation reveals thick nerve fibrils and filaments | Absence of nerve fibrils on silver impregnation |

| S-100 immunostaining is weak and patchy | S-100 immunostaining is strong and diffuse |

| Recurrence malignant transformation common | Psuedorecurrence (due to incomplete resection)Uncommon malignant trnasformation |

| Diligent, extensive follow-up required | Complete resection will suffice. |

Conclusion

The plexiform type of schwannoma is a rare, benign neural tumour prognostically distinct from plexiform neurofibroma. Awareness of this subtype, especially in biopsy material is crucial in dictating the treatment. Judicious use of cytochemical and immunohistochemical stains can aid in the accurate diagnosis of PS, which needs adequate surgical removal without extensive follow-up, unlike PN.

Financial or Other Competing Interests

None.

Patient consent was obtained before publication of this work.

[1]. Woodruff JM, Marshall ML, Godwin TA, Funkhouser JW, Thompson NJ, Erlandson RA, Plexiform (multinodular) schwannoma: a tumour simulating the plexiform neurofibromaAm J Surg Pathol 1983 7:691-97.10.1097/00000478-198310000-000096638259 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2]. Harkin J, Arrington JH, Reed RJ, Benign plexiform schwannoma: a lesion distinct from plexiform neurofibromaJ Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1978 37(5):62210.1097/00005072-197809000-00165 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[3]. Punia RS, Dhingra N, Mohan H, Cutaneous plexiform schwannoma of finger not associated with neurofibromatosisAm J Clin Dermatol 2008 9(2):129-31.10.2165/00128071-200809020-0000718284268 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[4]. Sheikh S, Gomes M, Montogmery E, Multiple plexiform schwannoma in a patient with NeurofibromatosisJ Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998 115(1):240-42.10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70464-7 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[5]. Ha Seong Lim, Jung J, Chung KY, Neurofibromatosis type 2 with multiple plexiform schwannomasInt J Dermatol 2004 43(5):336-40.10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01864.x15117362 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[6]. Enzinger FM, Weiss SW, Benign tumours of peripheral nerves In: Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft tissue tumours, Weiss. S, Goldblum JR (editors) 2008 5th editionSt LouisMosby:867 [Google Scholar]

[7]. Narsimha PA, Prakash S, Cristina RA, Deep seated plexiform schwannoma- a pathological study of 16 cases and comparative analysis with superficial varietyAm J Surg Pathol 2005 29(8):1042-48. [Google Scholar]

[8]. Shinde SV, Tyagi DK, Sawant HV, Puranik GV, Plexiform schwannoma in schwannomatosisJ Post Grad Med 2009 55(3):206-07.10.4103/0022-3859.5740619884750 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9]. Woodruff JM, Scheithauer BW, Kurtkaya-Yapicier O, Raffel C, Amr SS, LaQuaglia MP, Congenital and Childhood plexiform (multinodular) cellular schwannomaAm J Surg Pathol 2003 27:1321-29.10.1097/00000478-200310000-0000414508393 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[10]. Argenyi Z B, Goodenberger ME, Struass JS, Congenital neural hamartoma (fascicular Schwannoma): a light microscopic, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studyAm J Dermatopathol 1990 12(3):283-93.10.1097/00000372-199006000-000101693822 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[11]. Ducatman BS, Scheithauer BV, Piegras DG, Reiman M, IIstrup MD, Malignant Peripheral Nerve sheath Tumours- a clinicopathological study of 120 casesCancer 1986 57(10):2006-21.10.1002/1097-0142(19860515)57:10<2006::AID-CNCR2820571022>3.0.CO;2-6 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[12]. Posner MA, McMohan MS, Desai P, Plexiform schwannoma (neurilemmoma) associated with macrodactyly: a case reportJ Hand Surg 1996 21(4):707-10.10.1016/S0363-5023(96)80034-7 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[13]. Joste NE, Raez MI, Montogmery KD, Haines S, Pitcher JD, Clonal chromosomal abnormalities in a plexiform cellular schwannomaCancer Genet Cytogenet 2004 150(1):73-77.10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2003.08.01315041228 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]