Global pervasiveness of Carbapenem Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) have left seriously ill patient with multiple comorbidities, with minimal therapeutic option. Because of its features to remain a potentially endogenous reservoir in the human gut and simultaneously resistance to carbapenems poses a great deal of threat to inhabitants [1-4]. It has been recorded over the last 10 to 15 years time and again that asymptomatic faecal carriage of CRE introduces nosocomial infections [5,6]. Factors associated with CRE faecal carriage include antibiotic exposure, prolonged hospitalisation, malignancy, intravenous catheter use and admission to ICU [1,2,5-7]. Carbapenem are broad spectrum antibiotics usually reserved for severe life threatening infection and used for treatment of many enterobacterial infections, particularly caused by Extended Spectrum of Beta-Lactamase (ESBL) produced by Gram Negative Bacteria (GNB) and multidrug resistant bacterial strains [8]. Carbapenems may become resistant by enzymatic or non-enzymatic process. In majority of global cases carbapenem resistance are due to production of carbapenemase by bacterial cell, which directly inactivate carbapenems. So it is more appropriate to call CRE as CP-CRE (Carbapenemase Producing-CRE) or CPO (Carbapenemase Producing Organism) [6,9]. Gene encoding carbapenemase are typically located on plasmids and horizontal transfer between species is one of the reasons for their rapid widespread dissemination [9].

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted for the period of eight months in the laboratory of Division of Microbiology at Rajah Muthiah Medical College Hospital (tertiary care hospital), Annamalai Nagar, Chidambaram and molecular part of study was conducted at Helini Biomolecules, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. The research proposal was approved by the Institutional Human Ethics Committee with reference number IHEC/0371/2018 and written informed consents were obtained from the patients prior to sample collection.

Sample Size

Figuring of sample size was carried out on the basis of Daniel’s formula for cross-sectional studies. The formula used was n={z2 p (1-P)}/d2 [4]. In our study 11% prevalence of CRE was assumed for sample calculation after considering similar studies [3,4].

Inclusion criteria: All adult patients admitted from February to September, 2018 directly or transferred from other wards, to the surgery wards with 48 hours of hospitalisation, were taken up for the study. The answers were collected from the patients for the questionnaire which gives the demographic details, previous clinical history, dietary habits, etc.

Exclusion criteria: Paediatric patients, post-operative patients and Surgical ICU patients who cannot collect stool sample were excluded.

Phenotypic Methods

A pinch of stool sample was suspended in 2 mL of normal saline to get a uniform suspension of the sample in a test tube, followed by streaking on MacConkey agar plate and incubated at 35°C±2°C aerobically for 16-24 hours [15]. Lactose Fermenting colonies were further identified by standard biochemical reactions (Bailey and Scott’s Diagnostic Microbiology). To detect carbapenem resistance primarily, antibiotic susceptibility test was performed as per CLSI guidelines (2017) by using commercially available meropenem and imipenem disc (HiMedia) and resistant strains were stored [16]. Antibiotic susceptibility testing of these strains was also tested with Ceftazidime, Ceftazidime with clavulanate, Ciprofloxacin, Colistin, Cefotaxime, and Gentamycin as per CLSI guidelines [16].

Modified Carbapenem Inactivation Method Test

The test was performed to detect carbapenemase production. Here, broth cultures of isolates to be tested were incubated with 10 μg meropenem disc for 4 hours, followed by placement of same disc on a lawn culture of carbapenem susceptible E.coli ATCC 25922 strain. If the test strain is Carbapenemase enzyme producing strain, the drug Carbapenem present in the disc must have been utilised. So when the same disc was placed onto a lawn culture of carbapenem susceptible E.coli, there will be no zone of inhibition. Interpretations were made; no zone of inhibition indicates a positive test for CPO [16].

Modified Hodge Test

The test was performed by streaking a lawn culture of 1:10 dilution of E.coli ATCC 25922 strain to a Mueller Hinton Agar and allowed to dry for 3-5 minutes. A meropenem or ertapenem disk was placed in the centre of the test area, followed by straight line streak of the test strain from the edge of the disk to the edge of the plate, and incubated at 35°C±2°C aerobically for 16-24 hours. Interpretations were made; enhanced growth was seen at the intersection of the streak of test organism at the zone of inhibition was positive for carbapenemase production [16].

Epsilometer Test

It was carried out to detect ESBL (Extended spectrum beta lactamase) production by using E-strip method. One side of the strip was coated by ceftazidime (0.5 to 32 μg/mL) and the other side was coated with ceftazidime plus clavulanate (0.064 to 4 μg/mL), manufactured by biomerieux. The production of ESBL was confirmed by a ≥3 two-fold concentration decrease in an MIC (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration) for either antimicrobial agent tested in combination with clavulanate versus the MIC of the agent when tested alone [16,17].

Genotypic Methods

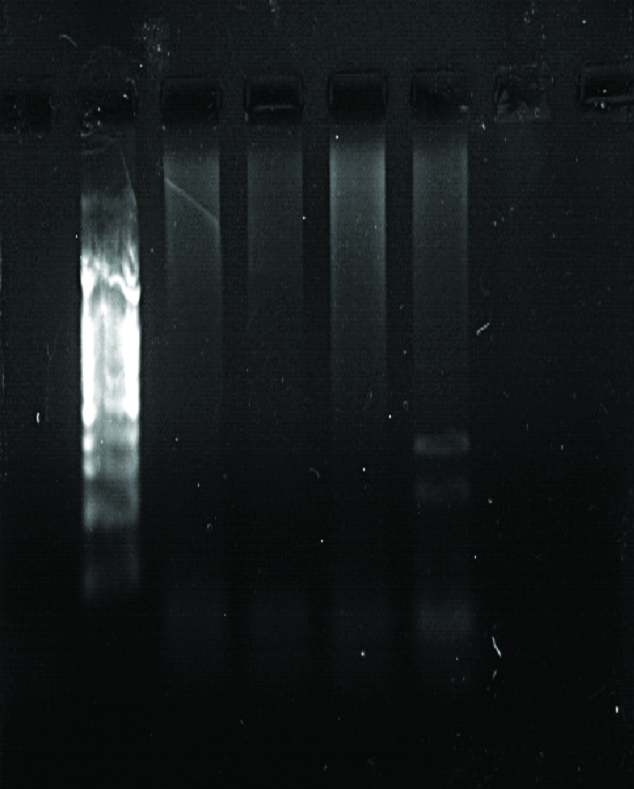

Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) was extracted using spin column method (PureFast® Bacterial DNA minispin purification kit, HELINI Biomolecules, Chennai, India) as per manufacturer’s instructions [18]. The purified DNA was put through multiplex PCR in a 20 μL total volume, in which, 5 μL was the primer mix (HELINI ready to use Gene Primer Mix), 10 μL was master mix (It contains 2U of Taq DNA polymerase, 10X Taq reaction buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 μL of 10 mM dNTPs mix and Red Dye PCR additives), and 5 μL was purified bacterial DNA. The primers used were designed and synthesised at HELINI Biomolecules, Chennai, India [19] and the sequence of the primers are mentioned in [Table/Fig-1]. Total volume was placed into PCR machine and was programmed as follows, Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 5 minutes, Denaturation: 94°C for 30 seconds, Annealing: 58°C for 30 seconds 35 cycles, Extension: 72°C for 30 seconds, Final extension: 72°C for 5 minutes. Agarose gel electrophoresis was carried out where, PCR products were loaded after mixing with gel loading dye along with 10 μL HELINI 100 bp DNA Ladder as a size marker. We waited till the dye reaches three fourth distances of the gel during Electrophoresis at 50V and Gel was viewed in UV Transilluminator and the bands pattern was observed.

Polymerase Chain Reaction primers and Amplicon size, Detection of Carbapenemase genes among CRE isolates.

| Sr. No. | Gene | Primers | PCR product (Amplicon size) |

|---|

| 1 | blaVIM | Forward: TCCGTGATGGTGATGAGTTGReverse: CGCTCGATGAGAGTCCTTCT | 115 bp |

| 2 | blaNDM-1 | Forward: GCAGCACACTTCCTATCTCGReverse: GTCCATACCGCCCATCTTGT | 202 bp |

| 3 | blaIMP | Forward: GCTTGATGAAGGCGTTTATGTTReverse: GCCGTAAATGGAGTGTCAATTAG | 387 bp |

| 4 | blaOXA | Forward: CTGAACATAAATCACAGGGCGTReverse: GAAACTGTCTACATTGCCCGAA | 360 bp |

| 5 | blaKPC | Forward: CGGCAGCAGTTTGTTGATTGReverse: CGCTGTGCTTGTCATCCTTG | 275 bp |

Statistical Analysis

Mean±Standard were used for continuous variables. Chi-square tests were used to analyse categorical variables. Mann-Whitney U-test was used where the data were found to be skewed for continuous variables. Univariate analysis was performed to get significant risk factor for CRE and Multivariate logistic regressions were performed using stepwise forward conditional algorithms to find out independent predictor of CRE. All statistical analysis were performed at a significance level of α=0.05, and were two sided. The analysis of data was conducted using IBM SPSS STATISTICS version 20.0, (New York, USA).

Results

In total 222 Enterobacteriaceae isolates were obtained from 156 faecal samples, 144 were E.coli, 74 were K pneumonia, and 4 were Enterobacter spp. Three isolates, one non-fermenter and two gram positive isolates were excluded from the study, as they did not belong to Enterobacteriaceae family. A total of 21 CRE isolates were obtained from 17 patients. The prevalence of CRE-fc (Faecal Carriage) among patient was (17/156) 10.89%, and isolates wise was (21/222) 9.45%. Out of total 17 CRE carriers, 13 (76.47%) were having only one CRE isolate, whereas 4 (23.52%) were carrying two different CRE species [Table/Fig-2].

Characteristics of stool sample and carbapenem resistant enterobacteriaceae.

| Categories | n (%) |

|---|

| Stool samples | |

| Total number of stool samples investigated | 156 |

| Total stool samples positive for CRE | 17 (10.89) |

| Stool sample with one species of CRE | 13 (76.47) |

| Stool sample with two different species of CRE | 4 (23.52) |

| Stool sample with CRE positive E.coli | 11 (64.70) |

| Stool sample with CRE positive K pneumoniae | 2 (11.76) |

| Stool sample with CRE positive E.coli and Klebsiella spp | 3 (17.64) |

| Stool sample with E.coli and Enterobacter spp | 1 (05.88) |

| Particulars of isolates | |

| Total number of Enterobacteriaceae isolates obtained | 222 |

| Total CRE positive isolates | 21 (09.45) |

| Total CRE positive E.coli | 15 (71.42) |

| Total CRE positive K pneumoniae | 5 (23.80) |

| Total CRE positive Enterobacter spp | 1 (04.76) |

| Total Isolates with CRE positive gene | 5 (23.80) |

| Particulars of genes | |

| Total number of 10 genes isolated from 5 bacterial isolates | 5 |

| CRE positive K pneumoniae with only blaNDM-1 gene | 1 (20) |

| CRE positive K pneumoniae with blaNDM-1 and blaVIM gene | 2 (40) |

| CRE positive K pneumoniae with blaNDM-1, blaOXA, and blaKPC | 1 (20) |

| CRE positive E.coli with blaVIM and blaNDM-1 gene | 1 (20) |

| CRE positive isolates with blaIMP | 0 (00.00) |

We had analysed the risk factors associated patients having intestinal carriage of CRE [Table/Fig-3]. The mean age of the patient having faecal carriage of CRE and patients not having carriage of CRE was 47.9±11.7 and 42.9±18.1, respectively and overall male were predominantly CRE positive. There was association between CRE carriers and usage of antibiotic ciprofloxacin to the patient (p=0.006). But more number of cases has to be studied to get a significant data. The other significant factors found were length of hospital stay (p=0.028), presence of haemorrhoids (p=0.005) and use of Intra Venous Catheters (p=0.010) [Table/Fig-3]. The use of Intra Venous Catheters and Haemorrhoids were found to be independent risk factors on multinomial logistic regression analysis [Table/Fig-4].

Univariate analysis of clinical characteristics associated with faecal carriage of carbapenem resistant enterobacteriaceae.

| Sr. No. | Characteristics (categories) | Total n/N (%), N=156 | CRE carriers n/N (%) n=17 | Non-CRE Carries n/N (%), n=139 | p-value (Pearson Chi-Square) |

|---|

| 1 | Age, (Mean±SD in years) | 43.5±17.5 | 47.9±11.7 | 42.9±18.1 | 0.091 |

| 2 | Sex (Male/Female) | 103/53 | 12/5 | 91/48 | 0.674 |

| 3 | Length of Hospital stay before CRE isolation (Mean±SD in hours) | 53.5±79.6 | 132.7±198.4 | 43.8±41.1 | 0.028 |

| 4 | Transferred from another ward | 19 (11.17) | 4 (23.52) | 15 (10.79) | 0.130 |

| 5 | Smoker | 13 (8.97) | 2 (11.76) | 11 (8.63) | 0.670 |

| 6 | Alcoholic | 30 (19.23) | 4 (23.52) | 26 (18.70) | 0.634 |

| 7 | Vegetarian/Non vegetarian | 58/98 | 5/12 | 53/86 | 0.483 |

| 8 | Diabetes | 7 (4.48) | 1 (5.88) | 6 (4.31) | 0.768 |

| 9 | Hypertention | 3 (1.92) | 0 (0.00) | 3 (2.15) | 0.541 |

| 10 | Inguinal hernia | 35 (22.43) | 4 (23.52) | 31 (22.30) | 0.909 |

| 11 | Haemorrhoids | 11 (7.05) | 4 (23.52) | 7 (5.03) | 0.005 |

| 11 | Cancer | 8 (5.11) | 1 (5.88) | 7 (5.03) | 0.881 |

| 13 | Intravenous catheter | 42 (26.92) | 9 (52.94) | 33 (23.74) | 0.010 |

| 14 | Amikacin | 2 (1.28) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.43) | 0.619 |

| 15 | Gentamycin | 7 (4.48) | 2 (11.76) | 5 (3.59) | 0.115 |

| 16 | Azithromycin | 3 (1.92) | 0 (0.00) | 3 (2.15) | 0.541 |

| 17 | Amoxicillin+clavulanate | 2 (1.28) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.43) | 0.619 |

| 18 | Piperacillin+tazobactam | 5 (3.20) | 1 (5.88) | 4 (2.87) | 0.507 |

| 19 | Cefoperazone+sulbactam | 2 (1.28) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.43) | 0.619 |

| 20 | Cefotaxime | 44 (28.20) | 6 (35.29) | 38 (27.33) | 0.491 |

| 21 | Cefoperazone | 1 (0.64) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.71) | 0.726 |

| 22 | Ceftriaxone | 2 (1.28) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.43) | 0.619 |

| 23 | Ciprofloxacin | 16 (10.25) | 5 (29.41) | 11 (7.91) | 0.006 |

| 24 | Levofloxacin | 2 (1.28) | 1 (5.88) | 1 (1.43) | 0.074 |

| 25 | Norfloxacin | 1 (0.64) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.43) | 0.726 |

| 26 | Metronidazole | 31 (19.87) | 6 (35.29) | 25 (17.98) | 0.091 |

| 27 | Antacid use | 116 (80.76) | 15 (88.23) | 111 (79.85) | 0.408 |

| 28 | Multiple classes of antibiotics use | 36 (23.07) | 7 (41.17) | 29 (20.86) | 0.061 |

Multinomial logistic regression of significant variables (OR: Odds ratio, SE: Standard error, CI: Confidence interval).

| Variables | OR | p | Coefficient for constant | SE | Wald | 95% CI |

|---|

| Lower | Upper |

|---|

| Intra venous catheter | 3.92 | 0.013 | -1.366 | 0.548 | 6.211 | 1.37 | 11.49 |

| Hemorrhoids | 6.57 | 0.010 | -1.884 | 0.730 | 6.666 | 1.57 | 27.77 |

All CRE isolates were sensitive to colistin and showed complete resistance to other antibiotics tested such as Ciprofloxacin, Cefotaxime, and Gentamycin. Moreover, the resistance rates were also high for 3rd generation cephelosporins, and b-lactam/b-lactamase inhibitors. A total of 13 (61.90%) out of 21 isolates were MHT positive, 6 (28.57%) were mCIM test positive, and 9 (42.85%) were E-Test (ESBL) positive [Table/Fig-2]. Out of 21 carbapenem resistant isolates 15 (71.4%) were E.coli, 5 (23.8%) isolates were K pneumoniae, and only one isolate was Enterobacter aerogenes. Four patients carried both carbapenem resistant E.coli and Klebsiella, where as one patient carried carbapenem resistant E.coli and Enterobacter aerogenes [Table/Fig-5].

Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of CRE isolates (ND* Not Determinable).

| Sr. No. | Isolates | Resistance to Meropemem | Resistance to Imipenem | mCIM test | MHT (Modified Hodge Test) | E-test | bla-VIM | blaNDM-1 | bla-IMP | bla-OXA48 | bla-KPC |

|---|

| 1 | E.coli | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2 | E.coli | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| 3 | K pneumoniae | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| 4 | E.coli | + | + | + | + | ND* | − | − | − | − | − |

| 5 | K.pneumoniae | + | + | + | + | ND* | + | + | − | − | − |

| 6 | E.coli | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 7 | K.pneumoniae | + | + | + | + | ND* | − | + | − | + | + |

| 8 | E.coli | + | + | + | + | ND* | − | − | − | − | − |

| 9 | E. aerogenes | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 10 | E.coli | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 11 | E.coli | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 12 | E.coli | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 13 | E.coli | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 14 | E.coli | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 15 | E.coli | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 16 | K.pneumoniae | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 17 | E.coli | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 18 | K.pneumoniae | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| 19 | E.coli | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 20 | E.coli | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 21 | E.coli | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

The prevalence of CRE gene among CRE isolates was (5/21) 23.80%. One isolate of K pneumoniae carried a single gene blaNDM-1-. The co-harbouring of blaNDM-1 and blaVIM was found in two Klebsiella spp, whereas one Klebsiella spp was found to be positive with three genes, they are blaNDM-1, blaOXA-48, and blaKPC. In contrast to this only one E.coli isolate harbours blaVIM and blaNDM-1 genes. Eventually, blaNDM-1 were found in five isolates, blaVIM were found with three isolates and blaOXA48, and blaKPC genes were found in one isolate each. All the CRE positive isolates were negative for blaIMP [Table/Fig-2,4,6].

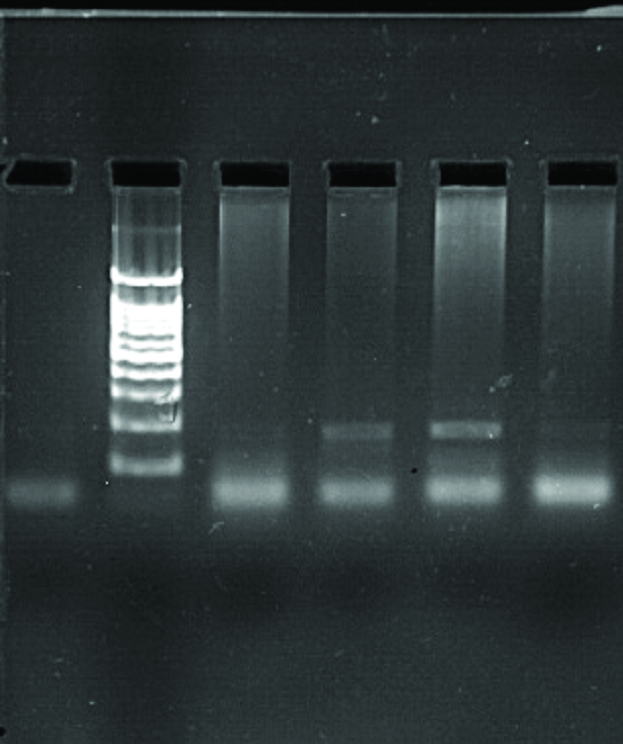

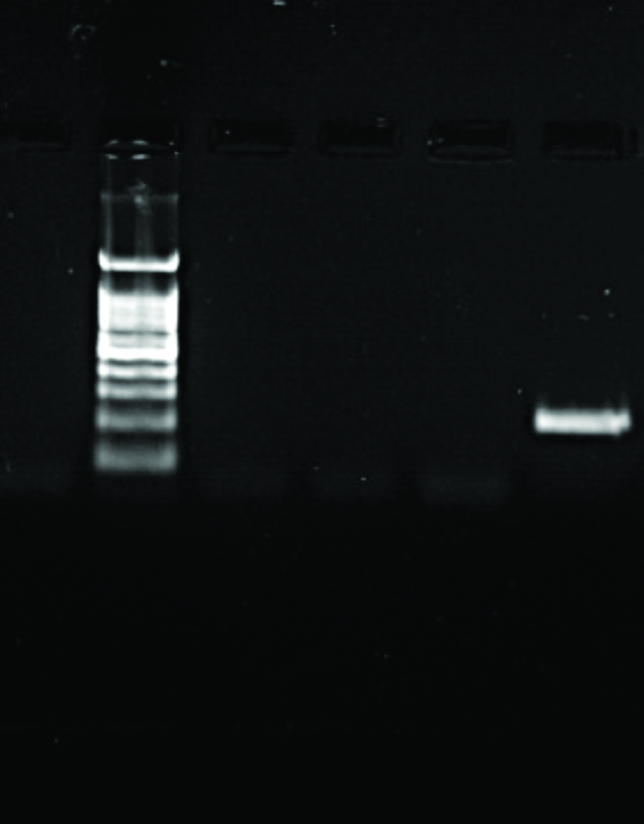

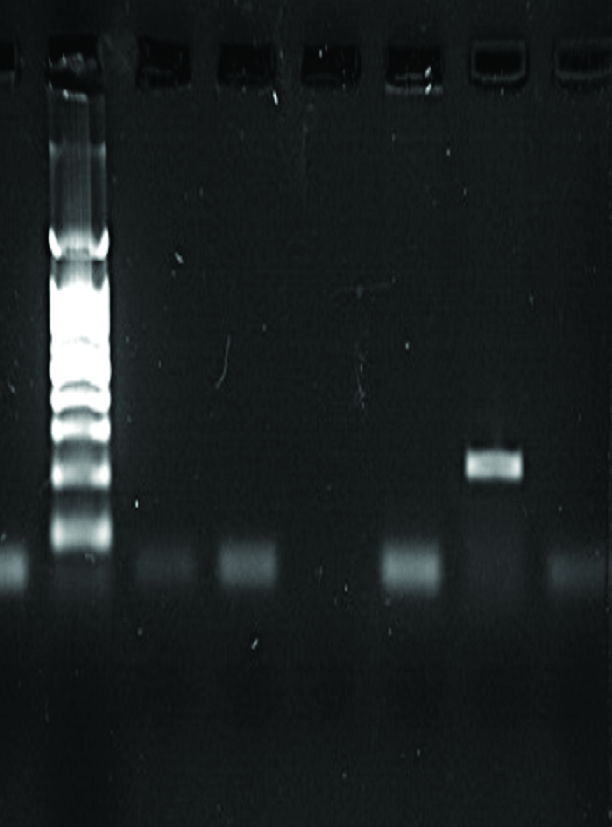

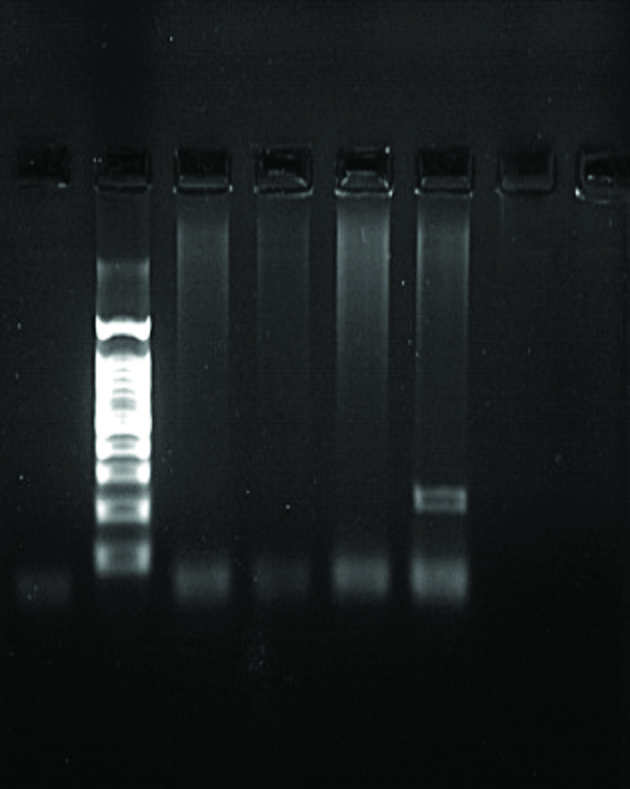

Gel documentation picture, where L: Ladder, NC: Negative Control and samples are designated as numbers.

| NC L PC 2 3 5 |

|

| VIM Positive: 2, 3 and 5 with 115 bp |

| |

| NC L 1 2 3 7 | NC L 15 16 17 18 | NC L 1 2 3 4 5 6 |

|  |  |

| NDM-1 Positive: 2, 3, & 7 with 202 bp | NDM-1 Positive: 18 with 202 bp | NDM-1 Positive: 5 with 202 bp |

|

| NC L 1 2 3 7 | NC L 1 2 3 7 | |

|  | |

| OXA 48 Positive: 7 with 360 bp | KPC Positive: 7 with 275 bp | |

Discussion

The presence of CRE in human stool is a probable factor for the development of infections caused by them [2,5]. The stockpiling of CRE in faeces opportunistically behaves as a source for its transmission and spread [3,5]. Gastrointestinal carriage of CRE isolates with multiple genes and multiple CRE isolates in the same patient have been documented in several studies including ours [2,9]. Overuse and misuse of various class of antibiotics in community, poultry, veterinary practices, aquaculture, agriculture, and medicine are reasons for man-made antibiotics pressure which also led to the emergence and spread of resistance gene [20]. In addition, global spread of carbapenem resistance gene is facilitated by poor sanitation, bad hygiene in community and in hospital [20,21].

The prevalence of CRE in stool sample is anxious, when we see all its aspects. In India there are only few studies, which focus on the prevalence of CRE in stool samples. Rai S et al., found a prevalence of 9.9% in a study from outpatient clinic in a tertiary care centre of east Delhi [22]. Faecal carriage of CRE among critical care patient from Mumbai was reported 51.85%, whereas, in another single centre study from Chandigarh, the prevalence of CRE was 18.1%, which also include ICU studies [4,10]. Thacker N et al., reported 20% prevalence of CRE faecal carriage in children with cancer from a prospective study from India [23], whereas, Datta P et al., reported CRE gut colonisation of 11% in ICUs, from a study conducted in north India [24].

Similarly, the prevalence of CRE faecal carriage in various parts of the world, in a study from Chinese university hospital, 6.6% was the prevalence of CRE faecal carriage [25]. Faecal carriage of CRE has been reported to be 2.6% in NewYork, and 2.4% in south France [26,27]. Chia PY et al., from Singapore, Abdalhamid B et al., from Saudi Arabia and Dandachi I et al., from Lebanon have reported a low prevalence of CRE faecal carriage; 1.5%, 0.5%, and 1.7%, respectively [28-30]. At the same time, some of surveillance study shows high prevalence of CRE from rectal swab such as 24% was in Israel, and 51.3% was in Greece [31,32]. We have recorded a prevalence of 10.89%, which is almost similar to studies conducted by Ho LP et al., from a healthcare region in Hong Kong and Zarakolu P et al., from a university hospital in Turkey, with a prevalence of 9.8% and 11%, respectively [9,33]. Contagious environment of hospital, antibiotic use prior to hospital admission could be the reason for such a high CRE faecal carriage.

In our observation maximum numbers of carbapenem resistant isolates were E.coli (71.42%), followed by K. pneumoniae (23.80%). Similar types of findings have been reported by Mohan B et al., from India and Dandachi I et al., from Lebanon [4,30]. However, K. pneumoniae (61.11%) is the leading isolates followed by E.coli (35.18%) in studies conducted by Solgi H et al., from Iran [2].

The variation in sensitivity among carbapenem group of antibiotics against CRE may be due to specific resistant mechanism or combination of more than one mechanism of resistance adopted. Some of such mechanisms for Non-Carbapenemase Carbapenem Resistance is mediated by specific point mutations in porins which can decrease the permeability of specific antibiotic selectively either by reduction of channel size or modification of electrostatics in the channel, mutations in penicillin-binding proteins, hyper production of ESBLs, coproduction of ESBLs and AmpC β lactamase or AmpC β-lactamases combined with porin loss, or production of more than one hydrolyzing enzyme [4,11,12,34].

As per CLSI guidelines, (2017) phenotypic determination of CRE can be carried out by Modified Hodge Test (MHT) and mCIM test [16]. The result of MHT in our study to demonstrate carbapenemase is nearly similar to other studies but mCIM Test for the same vary drastically with lower rate of positive findings. Above mentioned Non-carbapenemase carbapenem resistance mechanism might be responsible for variation in positivity during testing isolates [7,8]. ESBLs production has been measured using E-test with 42.85% of positivity among CRE.

Strains which were resistant to meropenem were subjected to molecular analysis. Overall 23.80% of CRE positive isolates harbour resistant gene. In our study blaNDM-1 is the lead finding carried by all the five CRE gene positive isolates, followed by blaVIM carried by (3/5) 60% of total CRE gene positive isolates. These two types of gene blaNDM-1 and blaVIM were also the lead findings by Mohan B et al., whereas Saseedharan S et al., detected blaIMP more in numbers, followed by blaNDM-1, blaVIM, and blaKPC from faecal carriage of ICU patients [4,10]. A similar study by Solgi H et al., from Iran detected blaOXA48 followed by blaNDM-1 and Pournaras S et al., identified blaKPC more in numbers followed by blaVIM [2,32]. The finding of various types of genes from different places may be due to endemicity or method of their spread.

Primarily, univariate logistic regression method was used for risk factors analysis of CRE faecal carriage [Table/Fig-3]. Secondly, multivariate analysis was conducted using stepwise forward conditional algorithm of all significant variables which were found significant on univariate logistic regression, where we found haemorrhoids and use of intravenous catheter as significant independent risk factors for gut colonisation by CRE.

Interpreting odd ratio; chance of CRE carriage in stool is 3.92 times higher among patient with Intravenous Catheter (IVC) as compared to patient without IVC. Similarly patient with haemorrhoids are 6.57 times more at risk for CRE faecal carriage as compared to patient without Haemorrhoids [Table/Fig-4].

Limitation

Because of demarcated time and resource, characterization of CRE using genotype methods were limited to five genes and only two test (MHT and mCIM Test) were conducted to determine carbapenemase production.

Conclusion

The present study from India reveals moderately high prevalence of 10.89% of CRE faecal carriage from surgery wards. Length of hospital stay, application of intravenous catheter, and haemorrhoids are significant factors associated with high faecal carriage of CRE among hospitalised patient. The study also helps us to understand the insight of prevalence, and spread of CRE. To institute authentic resolution more detailed surveillance studies are required, at the same time, our study suggests proper enforcement of antibiotic stewardship, and control measures to contain the spread of CRE.