Compulsory rotatory internship in Indian medical education lacks a structured formal assessment plan wherein the assessment is done through logbooks. Interns do maintain their logbooks in which they record the number of procedures they observe or do and get it signed by the faculty. However, this record does not reflect on how well the interns have performed. Also, the authenticity of the record is questionable. It does not reflect whether the interns are competent and skilful enough to perform the procedures accurately. After completing internship, they are licensed to practice as primary care practitioners. In the community practice, they come across many cases pertaining to ophthalmology but due to their lack of clinical skills, many times the patients are not managed properly. So, it is of utmost importance that interns are assessed with proper assessment tools by which the competence of interns can be reflected.

In Miller’s framework for assessing clinical competence, “Action” focuses on what occurs in practice rather than what happens in an artificial testing situation [1]. WPBA are one of the methods to assess highest level of Miller’s pyramid. This also provides information about performance in real life practice [2].

Another rationale for adopting WPBA is that it is focussed on clinical skills including the necessary soft skills (communication, behaviour, professionalism, ethics, and attitude), observation (in real situation) and feedback [2]. It is also better aligned with learning and actual working. Hence, to modify and improve the competency of a medical graduate, the results of various assessments could be useful for educators to modify their training programs as a process of quality improvement [3,4].

Mini-CEX and DOPS are some of the methods for skill assessment. Mini-CEX is used for clinical encounters and DOPS is used to assess procedural skills. Mini-CEX was introduced by the American Board of Internal Medicine as one of the series of assessments to address these issues [5]. The mini-CEX involves a short, focused observation of students encounter with patients live on various aspects of clinical skills such as history taking, examination skills, analytical skills, professional behaviour and overall clinical competence. Using standardised forms, examiners rate student performance along several predetermined dimensions and provide immediate feedback to students [6]. DOPS requires an assessor to directly observe a trainee undertaking a procedure and then grade the performance of specific predetermined components of the procedure [7]. In addition to the procedure itself, these skills also include communication and the informed consent process.

In context of ophthalmology, these assessment methods could be useful in teaching the interns various procedures and improve their clinical skills on daily encounters with patients. Globally, both mini CEX and DOPS are being used in postgraduates successfully [8]. However, authors propose that mini CEX and DOPS can also be successfully implemented for interns who are supposed to acquire skills necessary as a physician of first contact and improve them on necessary competencies. Hence, this study was conducted with the aim of introducing a formative assessment for interns using mini-CEX and directly observed procedural skill as assessment tools.

Materials and Methods

A prospective interventional study was carried out on the interns posted in Department of Ophthalmology of Punjab Institute of Medical Sciences, Jalandhar, Punjab, India. It was carried out during compulsory rotatory internship of 15 days after due clearance taken from the Institutional Ethics Committee (Regd no PIMS/DP/Gen/163/2302/spl dated 4/6/16). This study was carried out for a period of one year (June 2016- June 2017) on 100 interns.

The faculty of Department of Ophthalmology was then sensitised to the concept of mini-CEX and DOPS assessment and their role as assessors. Total of three faculty members participated as assessors, two of whom were trained in MCI certified, Advanced Course of Medical Education (ACME). The faculty included were: one professor, one associate professor and one assistant professor. An assessor training was carried out in which the assessors were shown presentations on need and how process of mini-CEX and DOPS was carried out. It was combined with demonstration of the process of assessing. They were also trained in giving feedback. Further evaluation points were discussed and a checklist was prepared for assessing. A consensus was formed on what topics need to be assessed. Topics to be discussed were a combination of common (refractive errors, cataract, infective conjunctivitis and allergic conjunctivitis) and emergency eye diseases (acute congestive glaucoma and central retinal artery occlusion). These patients were screened by assessors and then interns interviewed them. For procedure, refraction was selected to be assessed by DOPS. A pilot study was carried out on 50 interns who were excluded from the study to check the reliability of tools in the present setting. The overall raw alpha value of 0.77 was calculated (0.70 is the cut-off value for being acceptable). The design was then implemented for the study.

After informed written consent, 100 interns (during their posting in Department of Ophthalmology) were enrolled for the study over a period of a year. They were administered four mini-CEXs each and at least one DOPS over a period of 15 days of their compulsory rotation of internship. First two mini-CEXs were done in first seven days of their posting and next two mini-CEXs were done in the next seven days of their posting. First, DOPS was carried out during first five days of their posting and if result was unsatisfactory then further DOPS was undertaken in rest of the 10 days of their rotation till their performance was satisfactory. Each intern was at least assessed once by all the three assessors for mini-CEX. Structured feedback was provided to the interns after each encounter. A feedback questionnaire about the conduct and acceptability of assessment tools was taken from the interns and assessors at the end of their posting using a pre-validated questionnaire [Annexure 1].

Grading: The grading in mini-CEX in each sub-competency; medical interviewing skills, physical examination skills, professionalism, clinical judgement, counselling skills, organisation/efficiency and overall competence were recorded on a scale of 1 to 9(1-3 unsatisfactory, 4-6 satisfactory and 7 to 9 superior). The assessor and the intern then marked their satisfaction with the process of the assessment on a scale of 0 to 9 where 0 being the lowest and 9 being the highest. The time taken for observation of the intern-patient encounter and feedback given was recorded. The grading in DOPS was also recorded in each sub-competency: Clinical knowledge, consent, preparation, vigilance, technical ability, patient interaction and insight and documentation/post-procedure management separately on a scale of 1 to 9 (1-3 unsatisfactory, 4-6 satisfactory and 7 to 9 superior). The grading was done on the checklist (key points required) and evaluation done as per points pre-decided by assessors. Overall performance of the procedure was graded on a scale of 1 to 9 {mini CEX form in [Annexure 2] (http://www.abim.org/pdf/paper-tools/minicex.pdf) and DOPS sheet in [Annexure 3] (developed by authors)}.

Statistical Analysis

Data collected included average scores of all the interns in each sub-competency of mini-CEX. The scores were recorded and the progression of the scores was observed from first mini-CEX and the fourth mini-CEX. Comparison of scores was done between mini-CEX 1 vs. mini-CEX 4 using ANOVA Post-hoc Tukey’s Test. Average scores of all interns was recorded in each sub-competency for DOPS. Overall grading as satisfactory and unsatisfactory was collected for DOPS (1, 2, 3 and overall performance) and mini-CEX (1, 2, 3, 4 and overall performance). Thematic analysis of qualitative feedback collected was done.

Results

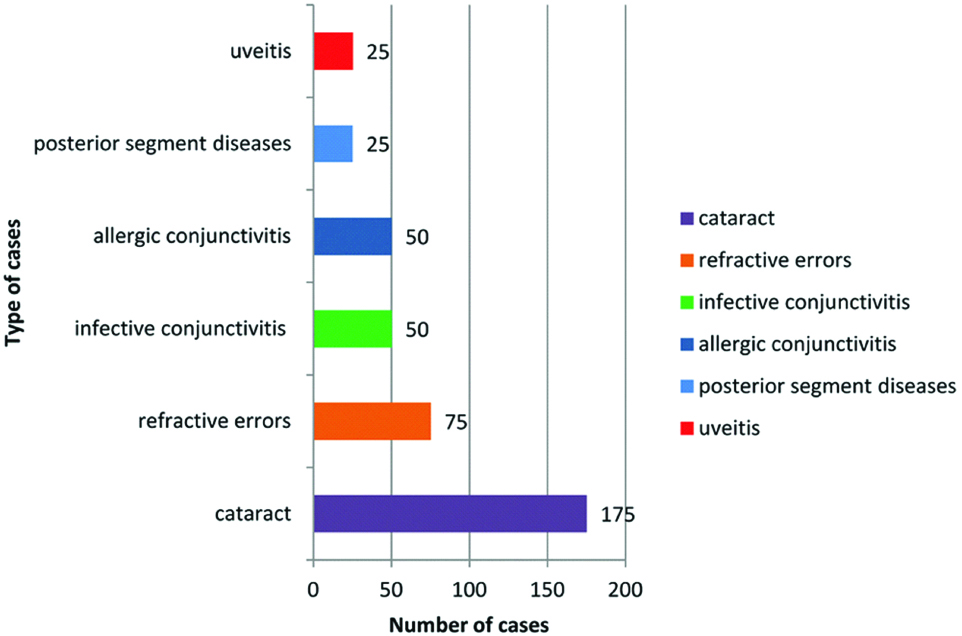

A total of 100 interns were enrolled in this study. The median {Interquartile Range (IQR)} age of the interns was 24.2 years (23-25 years) and 62 (62%) were females and 38 (38%) were males. Patients with common and emergency ocular diseases were interviewed by interns for making diagnosis [Table/Fig-1].

Different type of patients with different diagnosis encountered by interns.

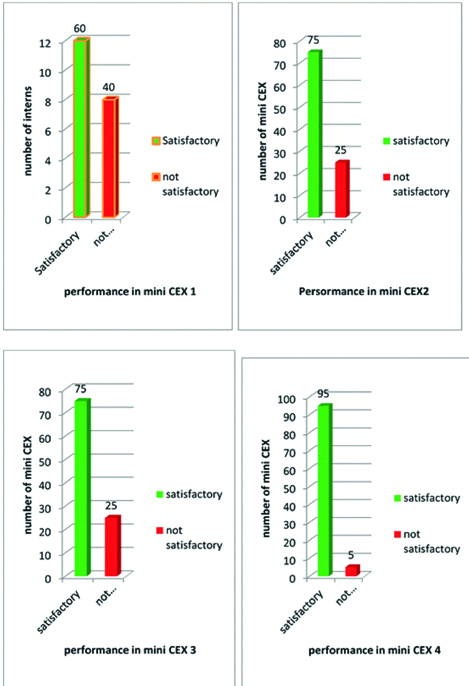

Mini-CEX results: The performance of interns as assessed by mini-CEX as satisfactory improved on subsequent mini-CEX (1 to 4) [Table/Fig-2]. Overall in the entire mini-CEX, 305 (76.25%) mini-CEX were satisfactory and 95 (23.75%) were unsatisfactory. Mean score of overall rating of all the 100 interns in 4 mini-CEX’s are shown in [Table/Fig-3]. There was an overall improvement in the mean scores in all the sub-competencies over the first mini-CEX to the last mini-CEX (p-value<0.05) as shown by ANOVA Post-hoc Tukey’s Test.

Grading as satisfactory/non satisfactory of mini CEX in first fourth setting.

Mean scores in various subcompetencies of 100 interns in Mini CEX 1, 2, 3 and 4.

| Sub competencies | Mini CEX 1 (mean scores) | Mini CEX 2 (mean scores) | Mini CEX 3 (mean scores) | Mini CEX 4 (mean scores) | p-value |

|---|

| Medical interviewing skills | 4.6 | 5.125 | 5.6 | 6.2 | <0.05* |

| Physical examination skills | 4.2 | 5.01 | 5.02 | 6.5 | <0.05* |

| Humanistic qualities/professionalism | 4.05 | 5.25 | 5.6 | 6.5 | <0.05* |

| Clinical judgement | 4.2 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 5.1 | 0.19 |

| Counselling skills | 4.0 | 4.7 | 5.6 | 6.35 | <0.05* |

| Organising efficiency | 4.0 | 5.2 | 5.6 | 6.0 | <0.05* |

| Overall clinical competence | 4.0 | 4.7 | 5.2 | 5.9 | <0.05* |

p-value significant only between Mini CEX 1 vs. Mini CEX 4 (Post-hoc Tukey’s Test).

Mean of evaluator satisfaction rate on a scale of 1 to 9 was 7.7. Mean of intern’s satisfaction rate with mini-CEX was: 8.0 (on scale of 1 to 9, 1 being low and 9 being high). Observation minutes mean: 14.5 minutes. Feedback minutes mean: 9.2 minutes

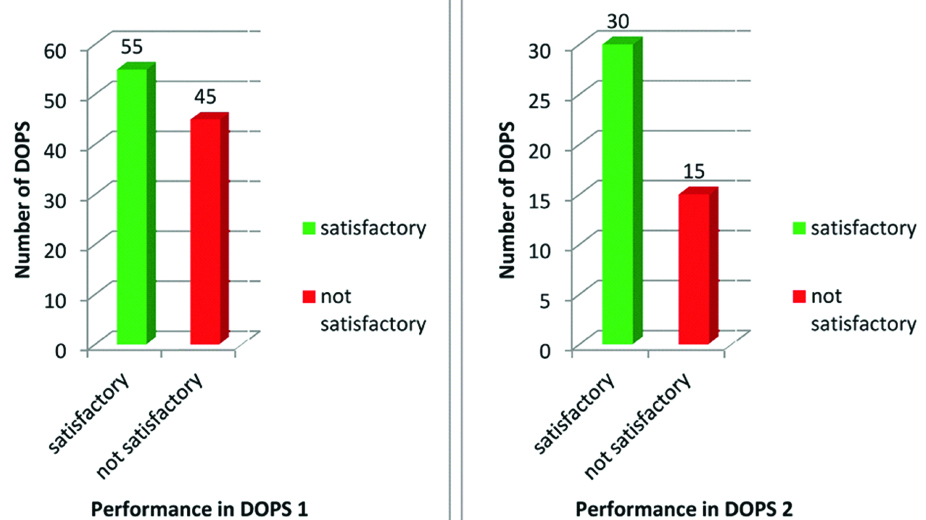

DOPS results: In DOPS 1, 55 interns (55%) performed satisfactorily and 45 interns (45%) performed unsatisfactorily [Table/Fig-4]. A total of 45 interns who performed unsatisfactorily in DOPS 1 undertook DOPS 2 out of which 30 interns performed satisfactorily and 15 performed unsatisfactorily [Table/Fig-4]. The 15 interns who performed unsatisfactorily in DOPS 2 underwent DOPS 3 and all of them performed satisfactorily. So in total 160 DOPS were conducted 100 were satisfactory (62.5%) and 60 were not satisfactory (37.5%). Overall performance of interns was 6.2 (scale of 1 to 9 where 1 being the lowest and 9 being the highest).

Grading as satisfactory/non satisfactory of first and second setting of DOPS.

On thematic analysis of feedback from the faculty and interns showed that 60 (60%) interns felt anxious when they were being observed performing procedure. All the interns and teachers perceived that this method of assessment has helped them to be more observant in this clinical posting, achieve higher confidence level and improve interpersonal skills and to analyse their strong and weak areas. All faculty members and interns gave a favourable response to the new program on feedback and expressed interest in continuing with it. All the interns felt that they are now more confident about dealing with patients. A total of 90% felt that through this process, the teachers spent more time teaching them than earlier. All the faculty members felt that this assessment method is feasible for interns and can give a quick overview of the competencies acquired by interns. They also perceived that now they are sure about what the interns know and where they need to improve.

Discussion

Workplace-based assessments were designed to facilitate observation, to give structured feedback on the performance of trainees in real-time clinical settings and provide a chance of improvement [9]. So, there is a need for formative assessment which offers trainees opportunity for feedback [10]. Traditionally, these assessment tools have been utilised for postgraduates but the present study has utilised these methods for interns. In the present study, mini-CEX and DOPS were used to evaluate an intern’s clinical performance in real life settings and improve it through structured feedback from an assessor for certain common eye diseases and routine eye procedure of refraction.

Satisfaction with process of conduct of mini CEX and DOPS: In the present study, satisfaction with the process of conduct and assessment with mini-CEX was also assessed and authors found high satisfaction rate with mini-CEX for interns i.e., 8.0 and 7.7 for faculty was seen and overall perception was positive. Some students were anxious due to direct supervision but after repeated mini CEX there perception towards the process was positive. For DOPS this factor was counteracted by making them understand that role of supervisor is not to judge but help you in improvement of the skill of refraction. Several studies have focused on teachers’ and students’ experiences with the mini-CEX showing that examiners as a group, were very satisfied with this method and mini-CEX was highly rated by students and evaluators as a valuable tool to document direct supervision of clinical skills [11-13].

The feedback about satisfaction with conduct of DOPS was similar and both faculty and interns found the direct observation and feedback on performance useful for acquiring required skills for refraction. Learning a procedure by observing, performing without guidance will not yield same results as performing under guidance and DOPS follows this strategy.

Improvement in performance for mini CEX: Use of min-CEX led to significant improvement in performance of interns in clinical encounters successively from first to fourth. The improvement was from 60% in first encounter to 75% in second and third encounter to 95% in fourth encounter. The improved performances were apparent in the higher mean scores progression of all the sub-competencies after each mini-CEX intern appeared in. Interns also showed remarkable improvement in medical interviewing skills and physical examination. The results of clinical judgement showed improvement but were not significant, reason may be owing to the fact that each case was different and was not discussed previously. The sub-competencies in which there was maximum improvement was Humanistic qualities/professionalism and counselling skills. This in concordance with a study of faculty development program to promote postgradute residents ACGME six core competencies, it was observed that residents learnt skills involving interpersonal and communication skills and patient care domains mainly from mini-CEX evaluation demonstrations [14]. So, mini-CEX is mainly helpful in developing soft skills related to communication and professionalism along with clinical skills.

Improvement in performance for DOPS: Out of total number of DOPS, 62.5% were graded satisfactorily and 37.5% were graded as unsatisfactorily in DOPS. Authors could not find studies for using them for interns for teaching refraction though the present authors found this tool helpful in teaching refraction to interns. The interns felt confident about performing refraction after undertaking DOPS in the present study.

Factors for improvement in performance: On thematic analysis of the feedback from the interns and faculty regarding the assessment tools usefulness and conduct, it was found that they owed the improvement in the skills to checklist of the subcompetencies given which makes it easier for them to understand what a clinical encounter or a procedure requires. The checklist not only helps in assessing but also helps in learning. The importance of checklists has been documented in literature in many studies both for trainee and assessor [4,15]. The second theme which helped the process of mini-CEX and DOPS to be effective was the feedback given at the end of each session. In the present study, mini-CEX and DOPS were found to be excellent tools for feedback session by interns and the faculty. As the feedback was immediately after intern-patient interaction, it helped interns correlate instantly to the case and hence the better understanding in the present study. Several studies in literature have stressed upon the inability of an effective feedback in form of mere marks for clinical assessment [16,17]. The feedback was perceived as detailed and discrete, self explaining the weak and strong areas which was similar as reported in other studies pertaining use of mini-CEX.

Action plan formulation during feedback sessions: The students and evaluators designed an action plan for overcoming the weaknesses of interns in their performance. This makes both students and assessor increase ownership of the performance. During feedback, the importance of these plans was emphasised by interns, they liked the planning process and reported that these plans acted as a guide to reinforce those skills which were done well and to give interns pointers or areas to improve on their weaker areas. It has been reported by other studies which emphasised role of mini-CEX feedback sessions in development of action plans together by mini-CEX supervisor and resident [18]. Such positive effects of feedback have been discussed in literature resulting in higher satisfaction [19]. Archer reported that feedback is a two way process and should not be driven by the person giving feedback, the person receiving feedback should be encouraged to self-reflect on their performance [20, 21].

Feasibility in clinical setting for mini-CEX: The present authors conducted these assessment sessions in the present outpatient department with an average inflow of 70 patients each day. Time taken for each assessment was observation average 14.5 minutes and feedback average 9.2 minutes per intern. During one posting, 4-5 interns are posted. So, it takes on average 23 minutes each day for this teaching learning strategy. Interns reported that the time given for this teaching learning method was adequate. For the authors, this strategy was very much feasible. Several authors have reported similar feedback time and found it to be adequate [22,23].

Feasibility for conducting DOPS: Interns were performing refraction under supervision of an optometrist earlier but were not observed. In this study, the authors observed and assessed the interns performing refraction. Though, authors have not recorded time required for observing and giving feedback for DOPS but the present authors perceived that it took few minutes extra and was feasible in the clinical setting.

Recommendations for future batches: Both interns and faculty felt the need of this direct observation based assessment tools. Interns found this assessment method acceptable and felt, it had a high impact on the learning. They felt this method of assessment should be continued for the future batches as it helped them gain confidence in their clinical skills. Faculty perceived that this assessment method helped them know what an intern has learnt and the areas they need to improve on. They perceived that this assessment method helps them to teach and assess at the same time. They found the method feasible and recommended continuation for future batches.

Limitation

Limitation of the present study was that it was conducted on one batch of interns and continuing the study on further batches will give us more insight on what other ways this teaching learning and assessment tool can be used. Though authors have now included it in the present assessment format for interns.

Despite no formal assessment during Internship, workplace-based assessment tools with in-built constructive feedback like mini-CEX and DOPS are effective, feasible and implementable for skills development for undergraduate students in Indian medical colleges. The present authors strongly recommend that medical schools in India should introduce this plan of assessment for teaching interns the competencies required from an Indian Medical graduate in various disciplines.

Conclusion

Assessment of clinical competence with mini-CEX and DOPS is very useful and this, eventually leads to better skill training. Mini-CEX and DOPS is also an effective tool for feedback. Using these methods for teaching learning in clinical setting is feasible and acceptable. Clinical competence of interns in ophthalmology can be improved through methods of mini-CEX and DOPS.

p-value significant only between Mini CEX 1 vs. Mini CEX 4 (Post-hoc Tukey’s Test).