Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS) is a chronic progressive inflammatory spondyloarthropathy typically involving the axial skeleton, especially the sacroiliac joints and spine. Genetic predisposition in AS leads to its common association with certain extra-articular diseases-anterior uveitis (25-30%), psoriasis (10%) and inflammatory bowel diseases (50%). Cardiorespiratory involvement in AS is rare and is usually present in long standing disease as restrictive lung disease, conduction abnormalities or aortic insufficiency. Here, we present a case of unusual AS in a 32-year-old non-smoker male with a major involvement of peripheral joints along with spine and chronic obstructive lung disease with apical fibro-bullous cavity and right sided heart failure over a short duration of disease course. His condition was acutely stabilised with diuretics, anti-hypertensive drugs, anti-pyretics, antibiotics and oxygen inhalation followed by maintenance on Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Hence, in a patient of AS, a strong index of suspicion should be there for both usual and unusual extra-articular manifestations and a complete work-up would help in early diagnosis and treatment.

Axial spondyloarthritis, Cavitary lung disease, Obstructive lung disease, Restrictive lung disease, Right heart failure, Seronegative spondyloarthropathy

Case Report

A 32-year-old male presented with a 5-year history of low back ache, knee and hip pain, insidious in onset, accompanied by morning stiffness with improvement on activity. The patient occasionally took pain killers from local pharmacies (Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs- NSAIDs), but he reported progressive restriction of spine, hip and knee movements despite treatment. Since last year, the patient started experiencing breathlessness, which had progressed from grade 1 to grade 4 (Modified medical research council dyspnoea scale) over time, with symptoms worsening on lying down. He developed progressive abdominal distension and pedal oedema since the last 1 month and fever for last five days. There was no history of chest pain, cough, haemoptysis, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea, jaundice, rash, involuntary movements, painful nodes on palms and soles, photosensitivity, recent gastro-intestinal or genito-urinary infection, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, neck pain, photophobia, eye pain and discharge, blood or mucus discharge per rectum, smoking, or family history of similar disease.

On general physical examination, bilateral pitting pedal oedema was noted. There was limited range of motion at bilateral hip and knee joint and difficulty in spine flexion with loss of cervical and lumbar lordosis. Modified Schober’s test was positive. Respiratory examination showed pectus excavatum [Table/Fig-1], decreased chest expansion, antero-posterior: transverse diameter ratio of 1:1, bilateral reduced air entry and vesicular breath sounds. The cardiovascular system examination showed raised jugular venous pulse, positive hepatojugular reflex. On auscultation, S1 and S2 were heard with a loud P2. A grade IV pansystolic murmur was present, best heard in the 4th and 5th intercostal spaces on the left side, which increased in intensity on inspiration. The central nervous system examination and slit lamp examination of the eye were unremarkable. The BADSAI was found to be 5.6.

Picture exhibiting pectus excavatum.

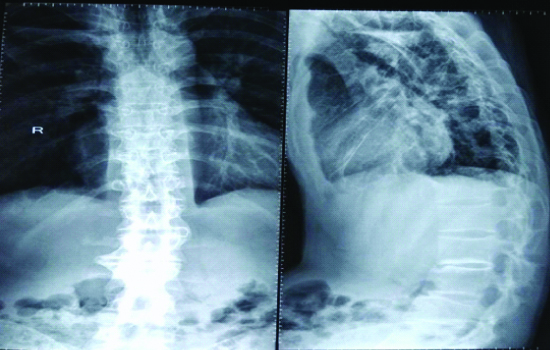

Routine blood and urine parameters were within normal limits. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was raised 25 mm/1 hr (Normal-0-15mm/1hr by Westergren method). Rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated antibodies, anti- nuclear antibodies, anti-streptolysin O titres were negative. Analysis of Human Leukocyte Antigen-B27 (HLA B27) was positive. Radiology of lumbar spine AP/lateral view showed decreased joint space and few osteophytes suggestive of early degenerative joint disease [Table/Fig-2]. X-ray pelvis, AP view, showed grade I sacroiliitis i.e., some blurring of joint margins [Table/Fig-3]. Chest X-Ray revealed a cavity in the right upper lobe with air fluid levels.

X-ray lumbar spine AP/lateral view showing decreased joint space and some osteophytes suggestive of early degenerative joint disease.

X-ray pelvis (AP view) showing grade 1 sacroiliitis (blurring of joint margins).

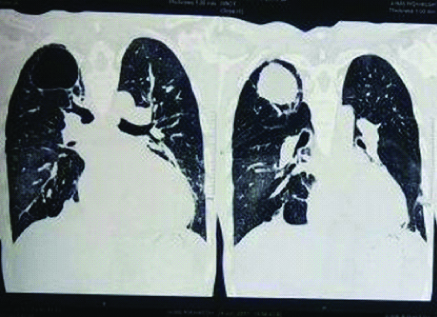

High resolution computed tomography of the chest showed a thin-walled cavitary lesion with an air-fluid level noted in the superior segment of right upper lobe. Mosaic attenuation was noted in bilateral lung fields [Table/Fig-4]. Sputum acid fast stain for bacilli was negative. Flexible fibre-optic bronchoscopy was performed which revealed minimum secretions and no visible endobronchial secretions. Culture of specimen obtained during bronchoscopy was negative for acid-fast bacilli staining and fungus aetiology but showed gram positive diplococci (most probably Streptococcus pneumoniae). A colonoscopy was done to rule out asymptomatic inflammatory bowel disease which showed no active microscopic and macroscopic abnormalities. Pulmonary function tests were done and showed severe obstructive pathology. A 2-D Echocardiography revealed pulmonary artery hypertension with right ventricular dysfunction with normal left ventricular function. Left ventricular ejection fraction was 60%.

CT chest (coronal view) showing a thin-walled cavitary lesion in the superior segment of right upper lobe with air fluid levels.

While evaluating the patient, there were a few differentials which were ruled out with the help of investigations and clinical examination. The foremost differential was rheumatoid arthritis with lung involvement (Caplan’s syndrome). The lack of major involvement of small joints of hands, lack of signs of inflammation, negative rheumatoid factor and negative anti-cyclic citrullinated antibodies helped to rule out rheumatoid arthritis. Reactive arthritis could also be a cause of morning stiffness and has HLA-B27 positive genotype. But the absence of past history of gastro-intestinal or genito-urinary infection, young male phenotype with typical involvement of spine and sacro-iliac joint made ankylosing spondylitis a more favourable diagnosis.

The patient was hospitalised and started on Inj. Furosemide 40 mg twice daily, tab telmisartan 40 mg once daily, tab. Paracetamol 500 mg twice daily, Inj. Ceftriaxone 1 gm IV twice daily and oxygen inhalation. He was kept in a propped-up position with regular blood pressure and input-output charting. These measures were taken upon admission to the inpatient unit and were continued for two weeks, whereby the patient’s cardiorespiratory status was sufficiently improved and subsequent cultures were negative. He was discharged on day 20 and started on a maintenance course consisting of tab. Telmisartan 40 mg OD, once daily NSAIDS for his pain and stiffness. He was also advised a low-salt diet intake and lifestyle changes. Since the patient had right sided heart failure, Infliximab could not be started. The patient returned to the outpatient clinic after a month and was symptomatically better, with repeat chest radiographs, showing no air fluid levels.

Discussion

Axial Spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a form of autoimmune inflammatory arthritis which comprises mainly of two subtypes: Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS) and non-radiographic axSpA (nr-axSpA) based on absence or presence of radiological findings. In AS, most commonly involved joints include sacroiliac joint and spine. Root joints (shoulder and hip) and other peripheral joint involvement occurs in 30-40% of AS cases approximately [1].

Respiratory involvement occurs in 0-30% cases of AS and usually occurs as restrictive lung disease due to parenchymal and musculoskeletal factors. Studies done by Sharif K et al., and Lai SW et al., have suggested association between Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and AS [2,3]. In the study done by Sharif K et al., [2], an increased risk of COPD was found in patients with AS as compared to controls (46% versus 18%, p<0.001) which was attributed to smoking. Our patient was a non-smoker but the risk of passive smoking, though less significant, cannot be ruled out.

The reported occurrence of a fibrocystic lesion in patients with axSpA is less than 1% - Crompton GK et al., (1 of 225 patients -0.4 percent) and Rosenow E et al., (26 of 2080 patients -1.3%) [4,5]. The most common infective aetiology being Aspergillus [5] or mycobacteria [6]. Other documented radiological pulmonary changes observed in AS include apical pulmonary fibrosis, subpleural nodules or parenchymal bands, bronchiectasis, paraseptal emphysema and tracheobronchomegaly [4,7]. Aspergilloma is usually described in pre-existing tuberculous and sarcoidosis cavity but it may occur in fibro-cavitary lesion in AS as observed in 5 of 2080 patients (0.2%) in the study conducted by Rosenow E et al., [5]. However, a study conducted by Ho HH et al., reported that TB instead of Aspergillus is the most common cause of apical fibrosis in AS [8] but in our case, it is none of both but Streptococcus pneumoniae making the conglomeration of the respiratory findings very rare.

Cardiac involvement which is considered another extra-articular manifestation, is uncommon, and is usually in the form of aortic insufficiency or conduction abnormalities [9]. Cardio-pulmonary manifestations in patients with AS mostly presents later in the disease course, usually 10-15 years after disease onset [4,5,9]. Apart from aortic involvement, involvement of myocardium has also been recognised in AS- a case report has been documented regarding left ventricular asynchrony [10]. Other reported findings include ischemic heart disease, strokes, venous thromboembolism, structural heart disease [11]. But right heart failure with echocardiographic findings of tricuspid insufficiency and pulmonary hypertension is a rare entity with not much data available.

Conclusion

Ankylosing Spondylitis should not be ruled out as a cause for obstructive lung disease. It can sometimes have unusual extra-articular manifestations in the form of cardio-pulmonary features, within a short duration of disease course.

[1]. De Winter JJ, van Mens LJ, van der Heije D, Landewe R, Baeten DL, Prevalence of peripheral and extra-articular disease in ankylosing spondylitis versus non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: A meta-analysisArthritis Res Ther 2016 18:19610.1186/s13075-016-1093-z27586785 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2]. Sharif K, Watad A, Tiosano S, Yavne Y, BlokhKerpel A, Comaneshter D, The link between COPD and ankylosing spondylitis: A population-based studyEur J Intern Med 2018 53:62-65.10.1016/j.ejim.2018.04.00229631757 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[3]. Lai SW, Lin CL, Association between ankylosing spondylitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in TaiwanEur J Intern Med 2018 57:e28-e29.10.1016/j.ejim.2018.08.00630098855 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[4]. Crompton GK, Cameron SJ, Langlands AO, Pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary tuberculosis, and ankylosing spondylitisBr J Dis Chest 1974 68:51-56.10.1016/0007-0971(74)90009-6 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[5]. Rosenow E, Strimlan CV, Muhm JR, Ferguson RH, Pleuropulmonary manifestations of ankylosing spondylitisMayo Clin Proc 1977 52:641-49. [Google Scholar]

[6]. Kanathur N, Lee-Chiong T, Pulmonary manifestations of ankylosing spondylitisClin Chest Med 2010 31(3):547-54.10.1016/j.ccm.2010.05.00220692546 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[7]. Quismorio FP Jr, Pulmonary involvement in ankylosing spondylitisCurr Opin Pulm Med 2006 12(5):342-45.10.1097/01.mcp.0000239551.47702.f416926649 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[8]. Ho HH, Lin MC, Yu KH, Wang CM, Wu YJ, Chen JY, Pulmonary tuberculosis and disease related pulmonary apical fibrosis in ankylosing spondylitisJ Rheumatoid 2009 36(2):355-60.10.3899/jrheum.08056919208564 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9]. Luckie M, Irion L, Khattar RS, Severe mitral and aortic regurgitation in association with ankylosing spondylitisEchocardiography 2009 26(6):705-10.10.1111/j.1540-8175.2009.00912.x19594817 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[10]. Kiris A, Karkucak M, Karaman K, Kiris G, Capkin E, Gokmen F, Patients with ankylosing spondylitis having evidence of left ventricular asynchronyEchocardiography 2012 29(6):661-67.10.1111/j.1540-8175.2012.01665.x22404185 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[11]. Gensler LS, Axial spondyloarthritis: The heart of the matterClin Rheumatol 2015 34(6):995-98.10.1007/s10067-015-2959-125957880 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]