Problem-Based Learning (PBL) is one of the most extensively researched areas in medical education [1]. It is defined as “an instructional method characterised by the use of patient problems as a context for students to learn problem-solving skills and acquire knowledge about the basic and clinical sciences” [2]. The four basic objectives of PBL are the structuring of knowledge to be able to apply it in clinical contexts, developing clinical reasoning skills, promoting self-directed learning and enhancing student motivation. The key features of PBL are the use of problems or triggers, small group discussions in the presence of a facilitator and periods of self-study [3]. The triggers are usually loosely structured clinical case scenarios that provide the context for learning. Discussions occur around these triggers, with students identifying their learning gaps in the process. These learning gaps are then addressed during the periods of self-study and learning consolidated in the subsequent group discussion session [3].

Self-Directed Learning (SDL) is defined as the “preparedness of a student to engage in learning activities defined by himself rather than a teacher” [4]. The Vision 2015 document brought out by the MCI lists life-long learning as one of the roles of the Indian Medical Graduate (IMG) [5]. One of the methods suggested achieving this is SDL. Seven key components of SDL have been described. These include the identification of learning needs, formulation of learning objectives, utilisation of appropriate learning resources, employing suitable learning strategies, commitment to a learning contract, evaluating learning outcomes and the teacher as a facilitator [6]. The evidence as to whether PBL enhances SDL is mixed [7]. The more common methods of assessing SDL include portfolios and self-rating scales [8]. A Concept Map (CM) is a visual depiction of information and is defined as “a schematic device for representing a set of concept meanings embedded in a framework of propositions” [9]. The three basic features of a concept map are general concepts, specific concepts and cross-links [9]. The few general concepts are usually placed near the top of a CM. Each general concept may be hierarchically related to one or more specific concepts which are placed lower down in the map. An important feature of a CM is the cross-links which depict relationships between different concepts [9]. Concept maps have been used in medical education to promote learning, as learning resources, to provide feedback and for assessment [9]. Concept maps have been incorporated into a number of PBL courses in health professions education [10-17].

The roles that an IMG is supposed to play are that of a clinician, communicator, life-long learner, professional, leader and researcher [5]. Of these roles, the traditional curriculum in most Indian medical colleges focuses mainly on the role of the clinician. The other roles are relegated to the hidden curriculum and are rarely if ever assessed. A short, two-month PBL course was introduced at St. John’s Medical College in 2008 to enhance student skills in knowledge acquisition, problem-solving, clinical reasoning, communication and leadership. Additionally, it was felt that PBL would improve the abilities of students in SDL and working in teams. The present study aimed to assess the effect of a two-month PBL course on the levels of self-directed learning and conceptual learning among 2nd year MBBS students.

Materials and Methods

The single group interventional study was conducted in the months of February and March 2017 at an urban private medical college in Southern India. Clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee prior to the commencement of the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants in the study. The subjects who underwent the short PBL program were 57 (31 females and 26 males) fourth semester medical students from the MBBS batch of 2015 with ages ranging from 18 to 25 years. All students in the batch were considered for the study. By this time, the students had successfully completed the pre-clinical component of the MBBS course and had attended one semester of classes in the para-clinical subjects. Additionally, they had attended their first major clinical postings in the subjects of general medicine, general surgery, obstetrics and gynaecology and community medicine. The first internal assessment for the second year MBBS had just been completed. Prior to taking part in the PBL program; the students attended a one and a half day PBL orientation workshop which dealt with literature search skills and the roles of students and facilitators in PBL. The students were divided into eight groups consisting of 7 to 8 students per group. The groups were selected to ensure nearly equal representation of males and females in each group. Each group was assigned two faculty facilitators. All faculty facilitators had undergone prior training in PBL facilitation. Three facilitators were from the pre-clinical departments, nine from paraclinical departments and four from clinical departments. It was ensured that no two facilitators assigned to a group were from the same department.

The Intervention

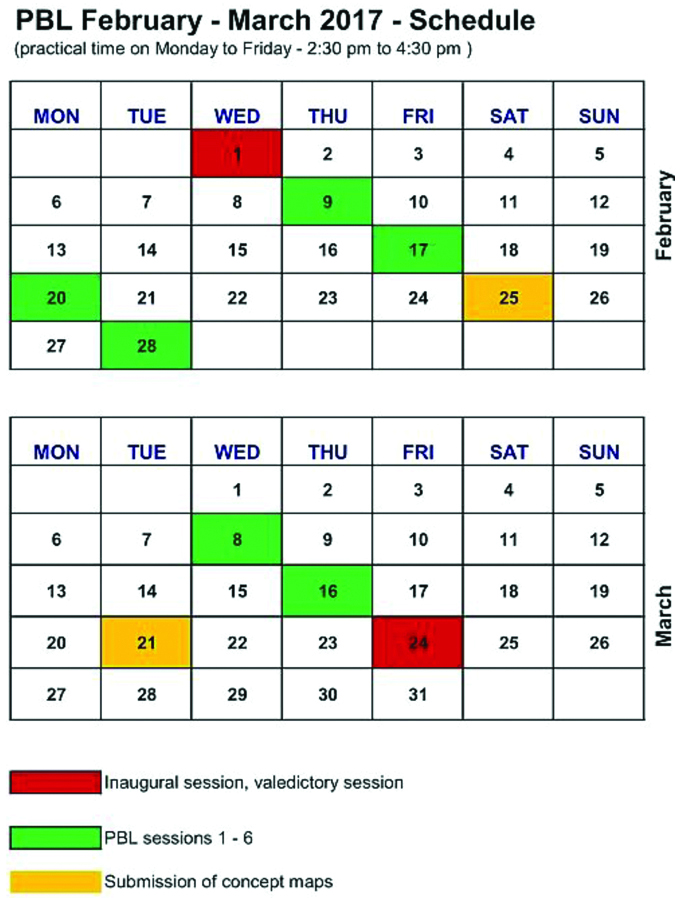

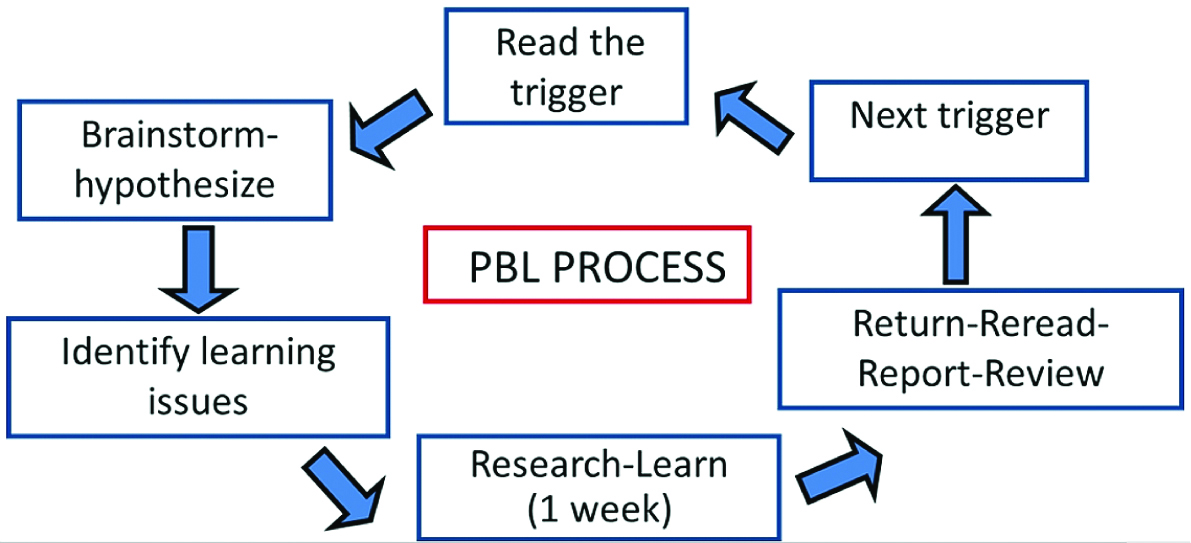

The schedule followed is shown in [Table/Fig-1]. During the initial session, students met with facilitators in their designated groups. Ground rules were discussed, and contact details were shared. The ground rules included compulsory attendance, adherence to session timings, adequate preparation for the sessions and active participation. The actual PBL sessions ran for six weeks. This consisted of two-hour sessions every week. Two problems (breast cancer and cerebrovascular accident) were discussed. Each problem had two triggers. The process that was followed is depicted in [Table/Fig-2]. The PBL sessions took place between ongoing traditional teaching methods.

The schedule that was followed for the short PBL course.

The steps that were followed for the PBL process.

Data Collection

The students completed a SRSSDL, modified from the scale developed by Williamson, before the beginning of the PBL course [18]. Permission was granted by the creator of the SRSSDL for its use in the present study. The original scale had 60 items which were reduced to 55 items, as five items were thought to be unsuitable for use in the context of the present study. The five broad areas assessed by the scale were awareness (10 items), learning style (10 items), learning ability (11 items), evaluation (12 items) and inter-personal skills (12 items) [Table/Fig-3]. Each item on the SRSSDL was graded on a Likert’s scale, with 5 and 1 indicating more inclination and less inclination respectively towards self-directedness. Thus, the maximum possible score was 275 (55×5) and the least possible score was 55 (55×1). Following completion of both PBL problems, students resubmitted the SRSSDL.

The self-rating scale for self-directed learning.

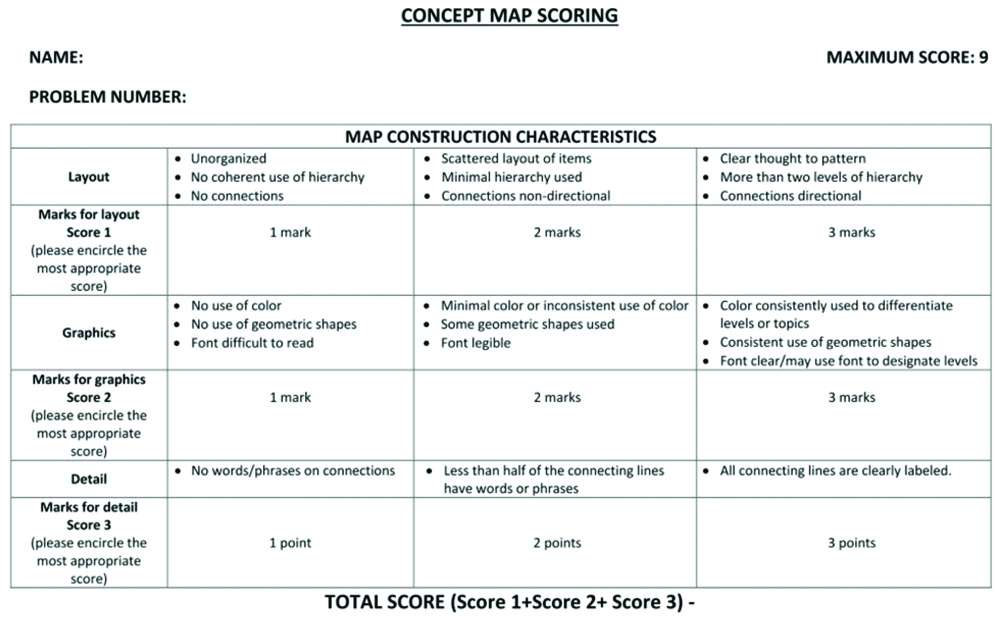

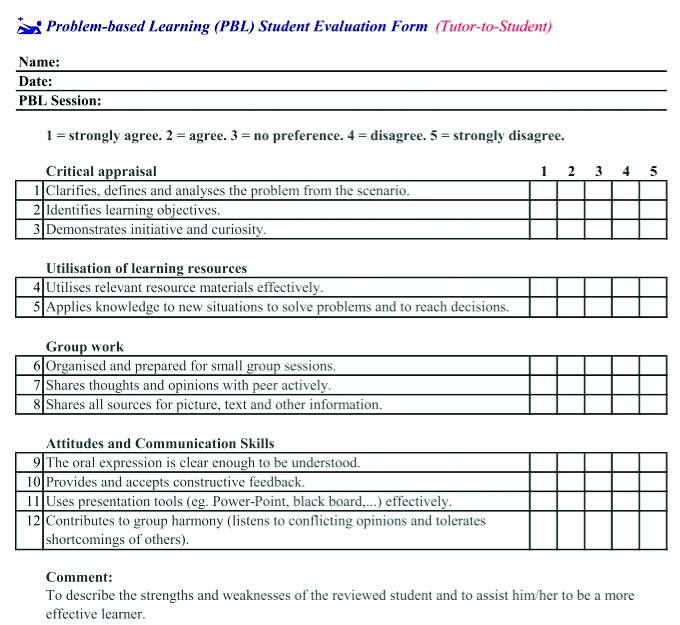

At the end of each problem, every student had to submit a concept map about the problem discussed. During the PBL orientation workshop, guidelines for the development of a CM, including the depiction of general concepts, specific concepts and cross links were shared with the students. The concept maps were anonymised and graded independently by two faculty members using a grading rubric modified from previously used rubrics [Table/Fig-4] [19]. The CM assessment rubric in the present study gave equal weightage to layout, graphics and detail. Each of the three mentioned parameters was scored from 1 (minimum) to 3 (maximum). Thus, the minimum and maximum marks that each rater could give a CM was 3 (3×1) and 9 (3×3), respectively. The layout included organisation of the content, levels of hierarchy and the effective use of connections. Graphics included the appropriate use of colour, geometric shapes and legible font. Detail referred to the use of labels for the connecting lines. The sum of the scores of the two graders was taken as the final score. Only the first concept map submitted by the students was considered for data analysis for this study. Data pertaining to attendance, gender and the tutor rating of the student was also collected. Attendance was calculated for seven sessions, i.e., the initial session and the six PBL sessions. The tutor rating was done using a rubric with 12 items related to the four domains of critical appraisal, utilisation of learning resources, group work and attitudes and communication skills [Table/Fig-5] [20]. Each item was scored using a Likert’s scale from 1-5. Thus, the maximum possible score for each student was 60.

The concept map scoring rubric.

The rubric used by tutors to grade student performance in the PBL discussions.

Statistical Analysis

The descriptive statistics included the mean and standard deviation of all the quantitative variables, namely the pre-program and post-program SRSSDL scores, CM scores, attendance and tutor ratings of students. The gender of the students was represented in percentages.

Inter-observer reliability for the CM scores between the two graders was estimated using the single measure Intra-Class Correlation Coefficient (ICC). The gender differences in the concept map scores were estimated by the independent sample t-test. Differences in CM sub-scores, namely, layout, graphics and detail were estimated using repeated measures ANOVA. The strength of association between the CM scores, attendance and tutor ratings were estimated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Finally, a multiple regression analysis was used to estimate the strength of association between the concept map scores (dependent variable) and three independent variables namely, gender, attendance and tutor rating. A p-value <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical package used was SPSS version 16.

Results

Effect of PBL on SDL

An amount of 53 of the 57 students completed the SDL questionnaire before the PBL program. Thirty-six students answered the questionnaire after the program. The pre-PBL and post-PBL Cronbach’s alpha scores for the SDL questionnaire were 0.96 and 0.97 respectively. The total and domain specific scores of the questionnaire are shown in the [Table/Fig-6].

The overall and domain specific scores for the SDL questionnaire.

| Category | Pre-PBL (mean±SD)* (n=53) | Post-PBL (mean±SD)* (n=36) |

|---|

| Overall score | 195±27 | 214±29 |

| Overall score per item | 3.5±0.5 | 3.9±0.5 |

| Awareness score per item | 3.7±0.6 | 4±0.5 |

| Learning style score per item | 3.6±0.6 | 3.9±0.6 |

| Learning ability score per item | 3.5±0.5 | 3.9±0.6 |

| Evaluation score per item | 3.5±0.5 | 3.9±0.5 |

| Interpersonal skills score per item | 3.5±0.6 | 3.8±0.6 |

*Data are presented as mean±standard deviation

Effect of PBL on Conceptual Learning

Fifty-seven students {31 (54%) females and 26 (46%) males} submitted their concept maps on the PBL problem related to breast carcinoma. The single measure ICC was 0.56 (p<0.001). The mean concept map score obtained by the students was 11.3±2.9. Female students had a mean score of 12.6±2.3 while the corresponding scores of the male students were 9.8±2.9. The mean sub-scores for layout, graphics and detail were 4.1±1.1, 3.9±1.2 and 3.4±1, respectively. When considered in pairs, the layout and graphics scores were significantly higher than the scores for detail. However, there were no significant differences between the layout and graphics scores.

Association between Conceptual Learning and Other Factors

The mean difference between the scores obtained by females and males was 2.8 (95% CI, 1.3-4.1, p<0.001). The average attendance of the students was 6.3±1.2, while the mean tutor rating was 50.4±9.4. On naïve analysis, all three independent variables correlated significantly with concept map scores (gender, r=0.47, p<0.001; attendance, r=0.34, p=0.005; tutor rating, r=0.47, p<0.001).

A multiple regression was run to predict concept map scores from gender, attendance and tutor rating scores [Table/Fig-7]. These variables statistically significantly predicted 2nd internal marks, F(3, 53)=8.7, p<0.001, R2=0.33. Both gender and tutor ratings added statistically significantly (p<0.05) to the prediction. Tutor rating scores (r=0.4, p=0.02) and female gender (r=0.35, p=0.004) were positively associated with CM scores. However, attendance (r=-0.07, p=0.69) did not contribute significantly to the prediction.

Multiple regression analysis to predict concept map scores from gender, attendance and tutor rating scores.

| Independent variables | Adjusted correlation coefficients | p-value |

|---|

| Gender | -0.349 | 0.004 |

| Attendance | -0.067 | 0.690 |

| Tutor rating | 0.395 | 0.024 |

Discussion

The primary aim of the present study was to assess the effect of a short PBL course on the level of self-directedness among 2nd year MBBS students. The second aim was to study the factors influencing conceptual learning among these students. Williamson developed the SRSSDL, which assessed the level of self-directedness rather than readiness for SDL [18]. This scale was shown to be valid and reliable [18]. The Cronbach’s alpha scores obtained in the present study suggest a high level of internal consistency. The present study showed an increase in the mean scores and scores for each of the broad areas in the SRSSDL [Table/Fig-6]. A number of previous studies have also shown significant increases in the level of student self-directedness after participation in PBL [11,21-24]. A three-month PBL intervention among paediatric residents produced a significant increase in the hours of independent study, hours of medical discussions, number of computer literature searches and total hours of self-study per week [21]. Significantly higher level in the skills of problem solving, scientific thinking and conflict resolution were noted among first year students who underwent PBL as compared to those who went through a traditional curriculum [23]. A significant increase on 11 out of 14 items on a modified self-assessment of self- learning skills scale was noted from the first to third year among medical students in a PBL curriculum [24]. A hybrid PBL curriculum produced a significant increase in the levels of SDL among first year medical students by the end of the first year [22]. A few other studies have not shown any significant increase in the levels of SDL after PBL [25-27]. Two of these studies were conducted among first year nursing students [25,26]. There were no significant differences in the levels of SDL between first year nursing students who underwent PBL and a lecture based traditional curriculum [25]. Similar, results were noted among first year nursing students in Canada before and after a PBL program. However, the students perceived themselves as having acquired some of the attributes of self-directed learners [26]. Another study among second year dental students found that a PBL intervention significantly increased the levels of SDL among small (three) and medium (six) sized, but not in large (nine) sized groups [27]. A particularly insightful qualitative study conducted among first year medical students suggested that peer interactions and faculty input for resources were more important for learning than self-directedness during PBL [28].

The results from the present study suggest that a short two-month PBL course for second year MBBS students incorporated into the traditional curriculum increases the level of SDL among them. Factors that probably facilitated SDL included the selection of second year students and group size. Students undergoing PBL had completed three semesters and were well adjusted to the medical school environment and their peers. They also had a sufficiently good pre-clinical knowledge base and clinical exposure in the hospital. The novelty of a new method may have played a role in enhancing learning. The medium size of the groups was also probably conducive to learning [27]. Several grading rubrics have been used to assess concept maps [19]. In the present study, layout, graphics and detail were considered for assessing the concept maps [Table/Fig-4]. Simplicity of assessment also needed to be considered in view of the large number of concept maps that had to be assessed. The ICC values in the current study suggest that there was fair agreement between the two assessors [29]. Previous studies have also shown good inter-rater reliability when concept maps were used for assessment [30–32]. Concept maps have been used in PBL programs in the past either to facilitate the PBL process [10,11,14,16,33] or as an outcome indicator of learning [12,13,15,17]. Incorporation of concept mapping into the PBL process was found to improve the perceptions of students about four learning domains namely, affective, cognition, metacognition and interpersonal relationships [10]. When concept maps were introduced into a PBL curriculum, the metacognitive processes of the students appeared to improve [16]. First year medical students who utilised concept maps as part of the PBL process showed significantly higher scores in the final examination as compared to those who did not [33]. Qualitative analysis revealed that concept maps helped students identify knowledge gaps, integrate information and challenge their knowledge [33]. The concurrent use of concept maps with PBL suggested that concept maps appeared to complement the PBL process [14]. A significant short and long-term increase in critical thinking and SDL was noted when PBL was used along with concept mapping as compared to traditional didactic methods [11]. Significant positive associations were noted between the concept map scores and grade point average scores and tutorial process evaluation scores [17]. The use of concept maps with PBL improved learning and creative thinking [13].

In the present study, CM scores were used as an outcome indicator of conceptual learning. The CM sub-score analysis suggests that students’ abilities in depicting propositions and hierarchies exceeded those related to forming cross linkages. In a similar finding, first year nursing students exposed to a PBL curriculum showed significantly higher CM scores and sub-scores (propositions and hierarchies, but not cross linkages) as compared to students who went through a traditional curriculum [15]. In another study, among third year occupational therapy students, significantly higher sub-scores in all three areas, namely propositions, hierarchies and cross-linkages were noted among students who went through BPL as compared to a traditional curriculum [12]. Female students had higher CM scores in this study. A study conducted among first year medical students, showed that female PBL groups demonstrated significantly better cognitive and motivational characteristics [34]. Another study conducted among third year medical students showed that PBL groups led by female students showed better group performance [35]. Female undergraduate students showed higher levels of cooperation and greater receptivity to feedback than their male counterparts during PBL sessions [36]. A plausible explanation for these findings is that interpersonal and communication skills appear to be better developed in females. Females are more likely to provide support and build consensus with team members. Males on the other hand tend to be more individualistic and domineering [35]. Creating empathetic connections seem to be an important motivating factor among females [35]. It was noted with interest that gender differences in PBL were reported frequently in the Middle Eastern countries [34-36]. It is likely that socio-cultural factors influence gender differences in PBL. These factors could also have played a role in the present study.

In this study, it was noted that there was a significant positive correlation between tutor ratings and concept map scores. Thus, students who were perceived by the tutors to perform well in the PBL process namely, critical appraisal, utilisation of learning resources, group work, attitudes and communication skills also obtained better CM scores. This indicates that tutor ratings can serve as an important proxy indicator of the level of knowledge gain among students. A previous study among first and second year dental students also reported significant positive correlations between PBL process grades and content acquisition assessments [37]. Another study among first and second year dental students showed a significant positive correlation between PBL group interaction levels and test performance among first year dental students. However, no significant correlations were found among the second year students [38].

Limitation

The response rates for the post-PBL SRSSDL were lower as compared to the pre-PBL response rates. Paired responses were not gathered so as to maintain anonymity. This precluded the use of inferential statistics to estimate differences in the pre-PBL and post-PBL SRSSDL scores. The long-term effects of PBL on SDL were not assessed. A randomised control study design would have been an ideal one to study the effects of PBL on SDL and conceptual learning. However, due to logistic constraints and ethical considerations, this was not possible. Only a single concept map score was used to assess conceptual learning. Using more concept map assessments would have improved the reliability of the assessments.

Conclusion

This study showed that the levels of student self-directedness increased after a two-month PBL intervention. The concept map assessments suggest that students were better at identifying propositions and hierarchies than creating cross linkages. Gender and tutor ratings were significantly associated with concept map scores. Female students and those students with higher ratings by tutors received better concept map scores. This study provides some evidence that a short-term PBL course positively influences self-directed learning and conceptual learning among undergraduate medical students. Incorporation of PBL in a conventional discipline-based curriculum can therefore be considered on a wider basis in Indian medical colleges. Further research could focus on the most effective ways of doing so.

Author contributions: Dr. Lakshmi, Dr. Nachiket, Dr. Mangala and Dr. Maria were involved in data collection, statistical analysis and writing the manuscript. Dr. Suneetha, Dr. Sanjiv and Dr. John were involved in planning the research project and editing the manuscript.