NETs include a diverse group of tumours varies by anatomic site and clinical behaviour. Not all but most of these tumours have lethargic clinical courses, small cell carcinomas and large cell carcinomas are highly malignant and have a poor prognosis, through with long endurance period even for the patients with metastatic illness [1-3]. NETs are uncommon malignancies which accounts for only 0.5 to 1 percentage of all malignancies [3-5]. The major portion of the NETs takes place in the gastrointestinal tract (67.5%) and the respiratory system (25.3%). GNTs traditionally known as carcinoids, have been now termed as gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumour due to the malignant impending of these neoplasms [1-5].

Most of GNTs cases are asymptomatic and symptoms raised during course of disease are mostly due to the fabrication of biologically active substances by tumour cells. GNTs usually present with obscure clinical features and require various investigations to establish the final diagnosis [6,7]. The diagnosis is based on clinical features, biochemical analysis, imaging, and confirmation with histopathology. A varied number of imaging techniques have been practiced for establishing the location of primary tumour as well as tumour extent [8,9]. The main problem in localising the small bowel carcinoid tumours are that, they may be very small and hence they are frequently missed by barium studies. Some of tumours can be picked up by angiography, Stereotactic Radiosurgery (SRS) or Computerised tomography (CT), but many of these are not seen even with these imaging modalities [4,8,9].

Biopsy and histopathology technique is the gold standard method for the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumours of GITs, which has witnessed frequent and numerous developments in laboratory based diagnosis and stemming from improvements in superior imaging techniques, and a deeper indulgent of the molecular mechanisms underlying tumour progression [10-12]. In recent times, the biological targeted agents have evolved with more sensitivity and specificity in patients with metastatic disease. Chromogranins and synaptophysin are group of proteins whose presence confirms neuroendocrine origin of the tumours and have been found relatively early in such cases. Somatostatin analogs take part in controlling the symptoms as well as they are infrequently linked to tumour regression. Chromogranin has improved sensitivity and specificity due to its content of antibodies panel directed to various epitopes of the protein. Synaptophysin is considered one of the most specific markers of neuroendocrine differentiation, manifesting more sensitivity than chromogranin A [13-17].

The purpose of this prospective study was to analyses the clinico-pathological aspects of GNTs and their anatomical distribution in GITs. We also carried out immunohistochemical study with synaptophysin and chromogranin, Ki-67 index to grade the Gastro-entero-pancreatic NETs.

Materials and Methods

This prospective study was carried out during March 2017 to June 2018, on patients who were diagnosed and managed as a case of gastroenteropancreatic NETs at Sri Ramachandra Medical College and Research Institute during the study period. Study protocol and procedure were permitted by the Research and Ethics Committee at Sri Ramachandra University, Chennai, India (CSP-MED/17/Feb 34-30). Informed consent was obtained from all the patients explaining the nature of this study.

Inclusion Criteria

During the study period, those patients who were diagnosed and managed as a case of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours were included for the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients with other systematic disease and/or diagnosed for other tumour site were excluded from this study.

Anthropometric Measurements

At the time of admission, a detailed history was taken for every enrolled patient. For the patients diagnosed with GNTs based on histopathology, a database was created which accounts for data collection included sex, age, and clinical appearance, past medical history, investigations, drug history, treatment and outcome. Under details of clinical presentation information such as symptoms, extent of disease presentation, date of diagnosis, anatomical site of gastroenteropancreatic NETs and biopsy results.

Clinical Investigation

Treatment data incorporated type and details of surgical resection and adjuvant therapy. A qualified pathologist reviewed all tumours for histological proof of diagnosis and assessment of morphological and immuno-histochemical distinctiveness. Pathological data included whether resection borders were clear or involved (R0/R1), immunohistochemistry for synaptophysin and chromogranin. Patient tumour characteristics and treatment variables were also analysed. Resection was classified as partial when gross residual disease was there at the end of resection. Complete resection was measured when all the gross disease was detached regardless of the microscopic margins.

Laboratory Investigation

Microscopic-pathological examination was performed using the standard haematoxylin and eosin staining and immunohistochemical stains using standard protocol earlier published [18]. For immunohistochemical staining, two antibodies chromogranin A (Mouse Monoclonal (LK2H10), IgG1, Kappa) and synaptophysin (Mouse Snp 88, IgG3, Kappa) obtained from Biogenex laboratories, India were used and staining was done as described in literature [19]. Immunohistochemical staining of Ki-67, which is a widely used proliferative marker, it was performed on the primary lesion as described previously. Ki-67 index was calculated as the percentage from 2,000 tumour cells in areas of highest nuclear labeling [20].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Fisher’s-exact test and chi-square tests were used to compare categorical data. The A two-tailed p-value equal to or less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

This study included a total of 47 patients, of which 43 patients were diagnosed with histopathological results and radiological appearance report and remaining four patients had clinical presentations and classical radiological appearance of NET. Majority of patients were in age group of 41 to 60 (40.5%) and above 60 years of age (42.5%). The youngest patient’s age was 19 and oldest being at age of 78 years. The mean age of presentation was 55 years. The highest incidence was found in the 6th decade of life. Male to female ratio was 1.93:1 in this study with male constituting 66% of patient’s population of the study group.

The commonest symptoms of study population included abdomen pain (16/47; 34%) followed by vomiting (9/47; 19%), dyspepsia (8/47; 17%), regurgitation (6/47; 13%) and one patient (2%) was asymptomatic. The most common primary site of tumour was duodenum (19/47; 40%), followed by stomach (8/47; 17%), pancreas (7/47; 15%), ileum (5/47; 11%), Appendix (3/47; 6%), ampulla (2/47; 4%), and one at liver, colon, and rectum [Table/Fig-1].

The commonest symptoms of study population.

| Symptoms (n=47) | Frequency | % | Site (n=47) | Frequency | % | Procedure done (n=47) | Frequency | % |

|---|

| Abdomen pain | 16 | 34 | Duodenum | 19 | 40 | Endoscopic Polypectomy | 27 | 57 |

| Vomiting | 9 | 19.1 | Stomach | 8 | 17 | Ileal resection | 5 | 11 |

| Dyspepsia | 8 | 17.4 | Pancreas | 7 | 15 | Appendicectomy | 3 | 6.7 |

| Regurgitation | 6 | 12.7 | Ileum | 5 | 11 | Enucleation | 2 | 4.2 |

| RIF pain | 3 | 6.3 | Appendix | 3 | 6.3 | Rectal polypectomy (TAMIS) | 1 | 2.1 |

| Jaundice | 2 | 4.2 | Ampulla | 2 | 4.2 | Central pancreatectomy | 1 | 2.1 |

| Hypoglycemia | 1 | 2.1 | Rectum | 1 | 2.1 | Whipples | 1 | 2.1 |

| Bleeding P/R | 1 | 2.1 | Colon | 1 | 2.1 | Right hemicolectomy | 1 | 2.1 |

| No symptom | 1 | 2.1 | Liver | 1 | 2.1 | Endoscopic biopsy | 1 | 2.1 |

| | | | | | Trucut biopsy | 1 | 2.1 |

| | | | | | Observation | 4 | 8.5 |

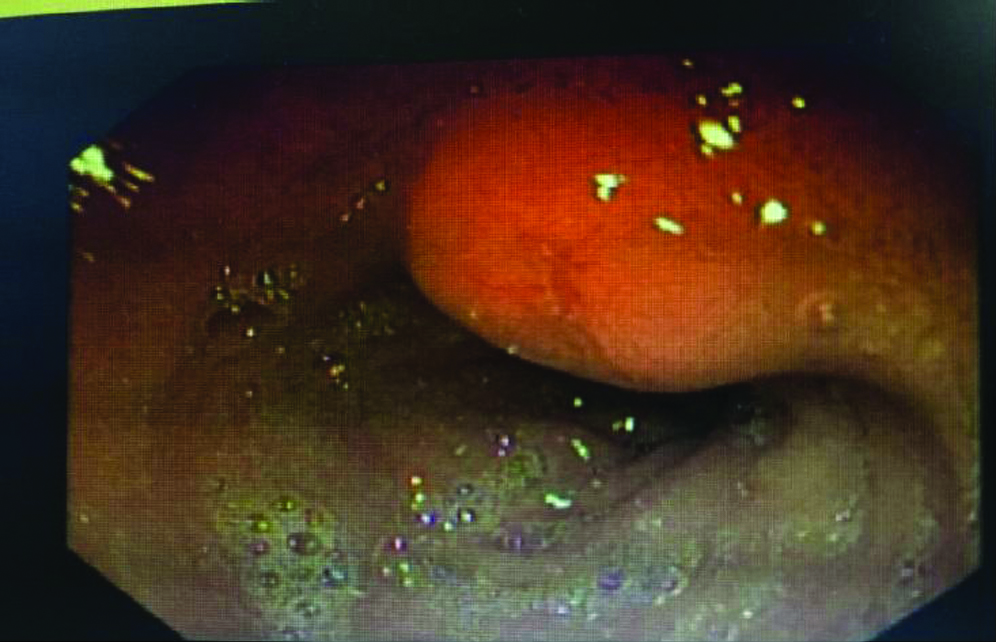

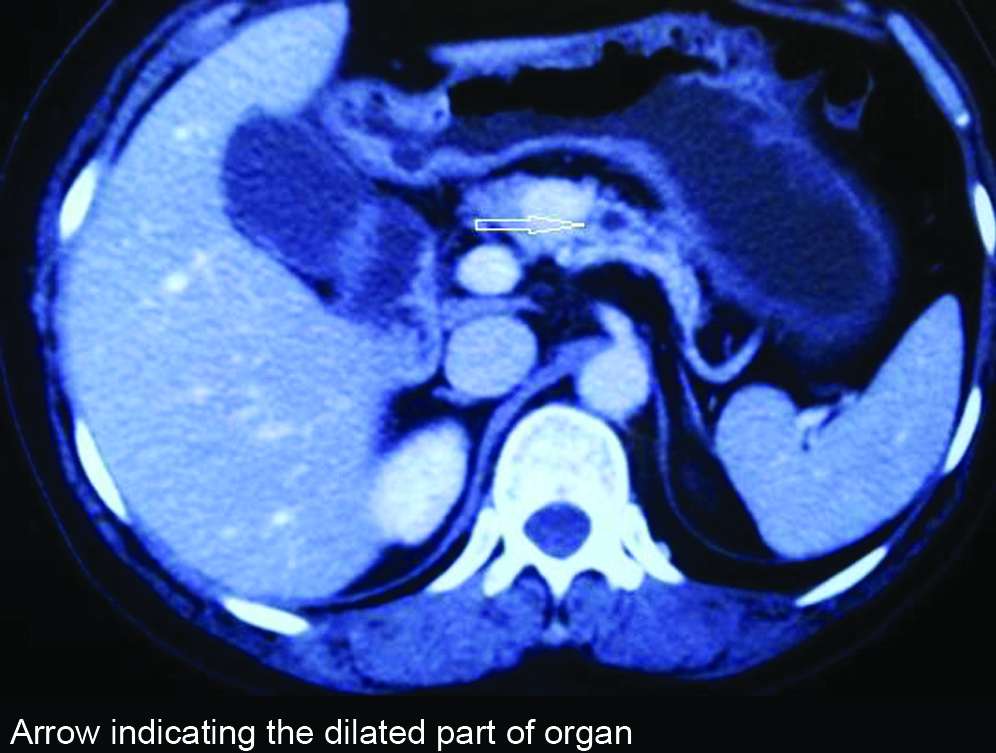

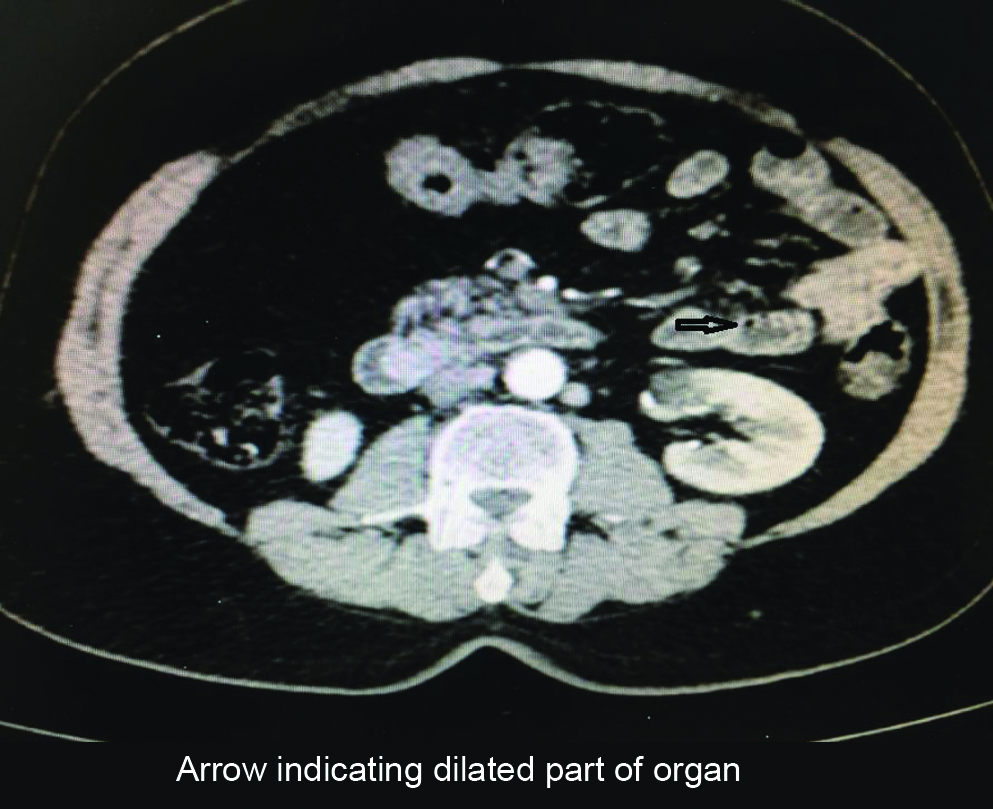

Most of the cases presented with duodenal polyp from first part of duodenum and stomach polyp was mostly from antrum. Among the study population of 47 patients, 19 patients underwent duodenal polypectomy for duodenal polyp in the first part of duodenum [Table/Fig-2]. Eight patients had gastric polyps [Table/Fig-3] for which they underwent polypectomy. Six patients had antral polyp, one fundal polyp and one from Gastro-Oesophageal (OG) junction. Three patients had lesion from the body of pancreas [Table/Fig-4], details are as follows. Two patients underwent enucleation of the lesion, intraoperative frozen section was sent to confirm the adequacy of margins and one patient underwent central pancreatectomy. Two patients presented with lesion in the ampullary region [Table/Fig-5] one underwent whipples procedure and the other patient underwent biopsy and stenting in view of liver metastasis. Five patients were presented with lesion in ileum; all patients underwent segmental ileal resection. Three patients underwent appendicectomy for appendiceal carcinoid. One patient with rectal polyp underwent TAMIS (Trans anal minimally invasive surgery). One patient with lesion in ascending colon underwent right hemicolectomy. One patient presented with longstanding Space Occupying Lesions (SOL) of the liver (5 years) with atypical features in CT scan, diagnosed to be a NET with trucut biopsy. Since patient’s functional residual volume was low, surgery was not done [Table/Fig-1].

Endoscopic images showed the duodenal polypectomy for duodenal polyp in the first part of duodenum.

Gastric polyps of one of eight patients indicating the presence of antral polyp.

Computer Tomography of patient’s pancreas showing lesion in the neck, enhancing contrast indicate dilated pancreatic duct (Heterogenous lesion in the head of pancreas avidly taking up the contrast, lesion encasing the superior mesentric vessels with enhancing vascular liver metastasis).

Computer Tomography of NET presenting as ampullary polyp causing dilatation of pancreatic duct.

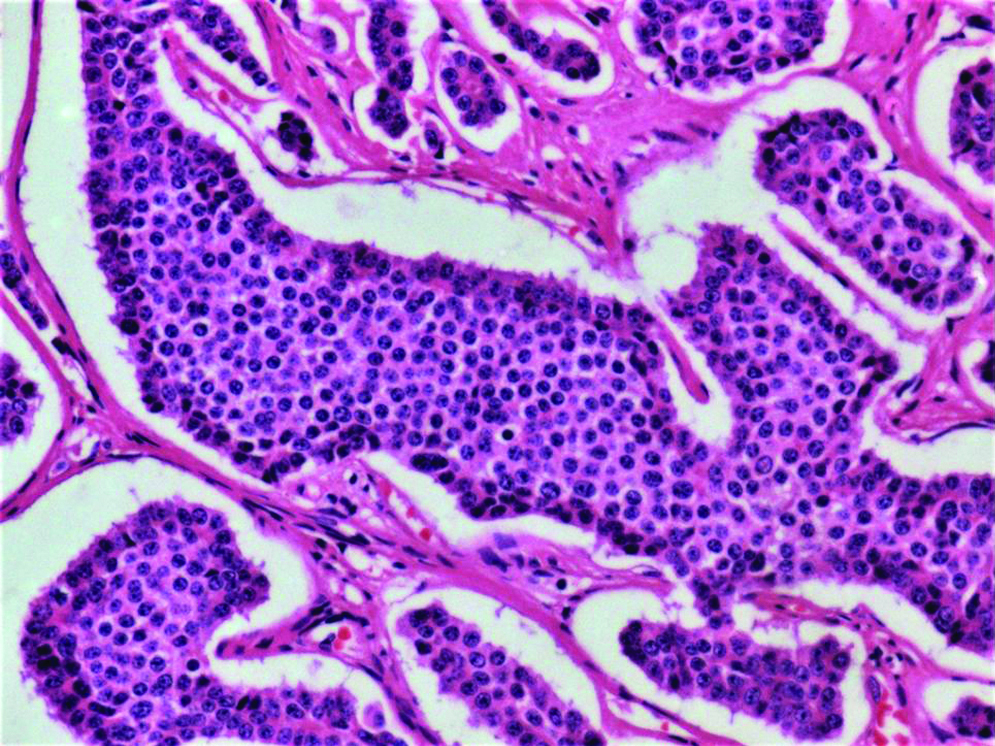

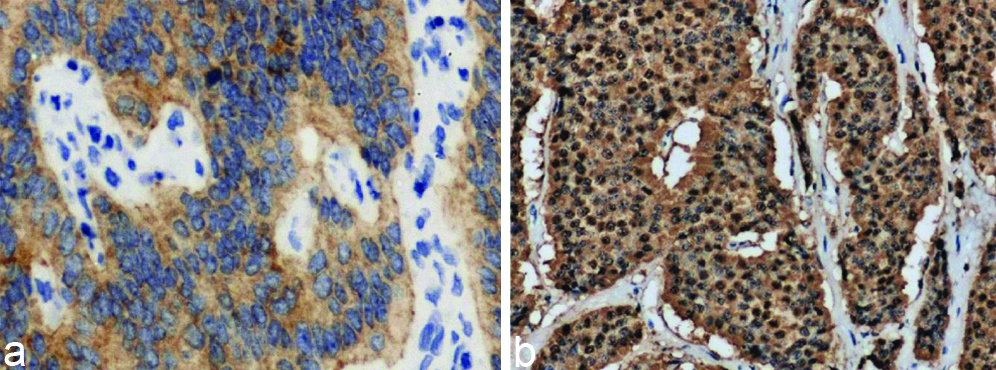

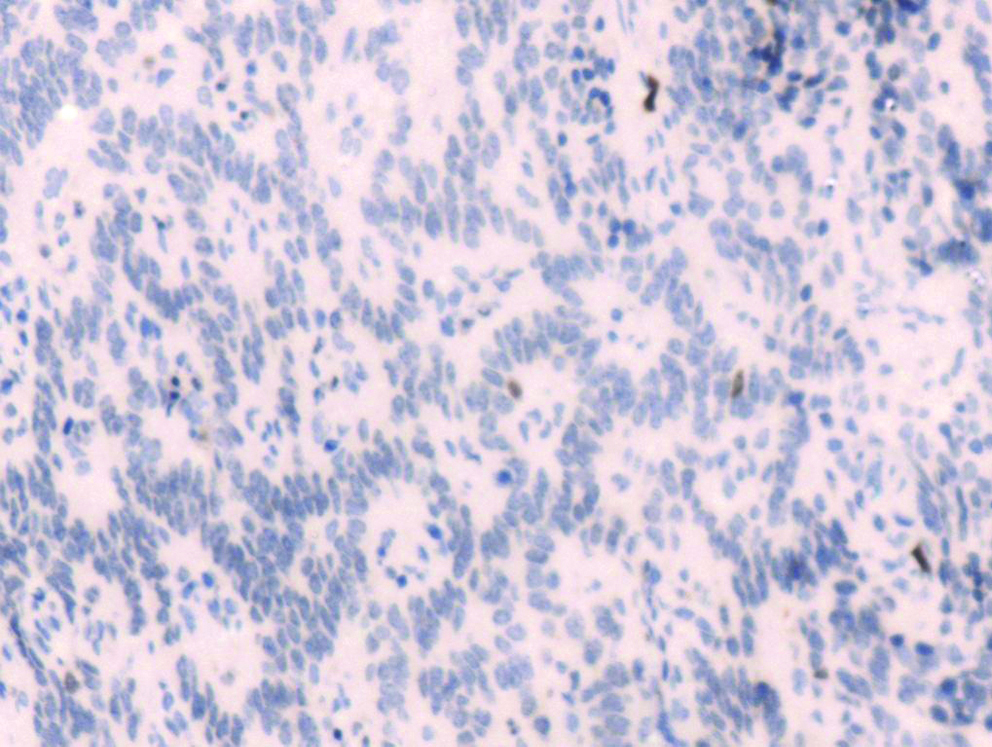

Biopsy and IHC was done only for 43 patients of study population, as the rest four patients did not turn up for follow-up tests. NET showed typical insular pattern and salt-pepper chromatin [Table/Fig-6] among that 43, 42 had non-functioning NET and rest one had functioning neuroendocrine tumour (insulinoma). Synaptophysin staining analysed qualitatively and was positive in 42 of 43 cases and focally positive in one patient. Similarly chromogranin was qualitatively positive in 39 out of 43 patients, focally positive in one patient and negative in 3 patients [Table/Fig-7]. Ki-67 index was <2% in 41 (95%) of the cases, it was <5% in 2 (5%) of the cases [Table/Fig-8,9].

Standard hematoxylin and eosin staining of neuroendocrine tumour showing insular pattern and salt and pepper chromatin (20X).

Synapatophysin (a) and Chromogranin (b) positive case of duodenal polypectomy and antral polyp (10X).

Ki-67 Index of study population.

| Ki67 Index | Frequency | Percent | ENETS/WHO 2010 proliferative grading |

|---|

| <1% | 19 | 44 | G1 |

| <2% | 19 | 44 | G1 |

| <1.5% | 3 | 7.2 | G1 |

| <4% | 1 | 2.4 | G2 |

| <5% | 1 | 2.4 | G2 |

| Total | 43 | 100 | |

G1=95%; G2=5%

Image showing the Ki-67 index <2%.

In 40 patients, margins were negative. One patient underwent enucleation for lesion in body of pancreas; frozen section margins were negative but turned out to be positive in final biopsy. It was advised to follow-up as it was grade1 non-functioning NET. Heterogenous lesion was usually seen in the head of pancreas avidly taking up the contrast, lesion encasing the superior mesenteric vessels with enhancing vascular liver metastasis. Case of von hippel lindau disease presented with glomus tumour and renal cell carcinoma underwent nephron sparing resection few years back now presenting with multiple cyst in the pancreas. Same patient presenting with NET in the head of pancreas size 8 mm with briliant enhancement on contrast. In one patient in right lobe of liver which was atypical features biopsy turned out to be NET. Grading was done following the Ki-67 index and results indicated that more that 2% of Ki-67 staining was seen in 5% of patients (n=2) which is considered Grade 2 and rest 95% (n=41) had Ki-67 index less than 2% of Grade 1.

Discussion

Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine tumours are rare malignant tumours and NETs account for only 2% of GI malignancy [21]. Due to enhanced diagnostic and therapeutic modalities, they have gained interest over the past few years. Around the world, there is inadequate epidemiological data offered for NET of GIT. At present, it is estimated that the incidence of Gastroenteropancreatic NETs is approximately 2.5 to 5.0 cases per 100,000 in the United States which indicates the low incidence of these tumours [4]. According to SEER database prevalence of NETs has increased considerably during past three decades and believed to have these tumours increased globally [22]. Substantial increase might be due to an increase in the number of cases and/or increased clinical facilitates and pathological experience of this disease. Hodgson N et al., have shown statistically significant increase of about eight to nine fold increase in the incidence of gastric NETs [23]. Modlin IM et al., have shown significant increase in incidence of gastric NET from 2.4 to 8.7% [24]. A study from India by Hegde V et al., has also shown rising incidence of gastric NETs as compared to the past [25]. An explanation for the increase may be the greater use of endoscopic diagnostic procedures and biopsies as a routine for all cases, even with small gastric lesions. The extensive use of proton pump inhibitors and increase in endoscopic biopsies has been found to be the reasons for the increased incidence of NET of GIT [26].

The mean age of presentation in our study was 55 years. All patients were between age group 19 years to 80 years. In study done by Rothenstein J et al., study of 193 patients with NET GIT had mean age of 56 years comparable to our study [27], while study done by Kapoor R et al., with 51 patients, mean age was 44 years [28]. Amarapurkar DN et al., have done a retrospective analysis of NET of GIT and Pancreas in 74 patients [29]. In their study the mean age at diagnosis was 53.01±15.13 years. In our study males had higher incidence of NET of GIT with 66%. The observed male: female ratio is 1.9:1. Most of the studies correlated well with our study. The same male preponderance was observed by Yao JC et al., (M: F=1.2:1) in USA [30] and by Ito T et al., (M: F 2:1) in Japan [31] and also by Niederle MB et al., (M: F=1.08:1) in Austria [9]. Rothenstein J et al., and Amarapurkar DN et al., also showed that males were commonly affected and found higher number of NETs in males [27,29].

The commonest site involved in our study was duodenum followed by stomach and pancreas. Our results were in contrast to results published by Kapoor R et al., the commonest site was pancreas (35%) and then periampullary region (21%) [28]. In a study done by Rothenstein J et al., the commonest site was midgut (40%) followed by foregut (35%) [27]. A study done by Pape UF et al., tumour arising from foregut was 44% and from midgut was 43.7% [32]. In contrast to other studies [1,3,8] where duodenal NET is rare (2-3%), in our study the majority of the cases were duodenal NET (44%). In our study pancreatic NET was 15% and ileum NET was 10%. This results were in contrast to study done by Kapoor R et al., in which most common NET was pancreatic NET [28]. Over a decade the controversy is existing between the small intestine and the stomach as the common site of occurrence of NET. Initially, stomach was suspected as the preferential site of NET of GIT, however now most of the studies revealed that the stomach as the commonest site of NET of GIT. Most of earlier studies have reported that stomach was the commonest site (22.8%) followed by appendix (21%), including study conducted by Amarapurkar DN et al., in India with stomach (30.2%) being the common site followed by pancreas (23.3%) [9,18,29].

The most common symptom in our study was pain abdomen (34%) followed by vomiting (19%). Our results are similar to study done by Niederle MB et al., whose common symptom was abdomen pain (29.5%) [9]. In our study of NET for duodenal and stomach polyp, all patients underwent endoscopic polypectomy (100%). This data is similar to study done by Kim SH et al., where endoscopic resection was done for 83% of patients with duodenal NET [33].

With emerging advanced imaging techniques, more tumours of the GIT tract or any other region are now frequently suggested for pathological evaluation. Pathological evaluation is now developed with use for few sensitive and specific marker such as synaptophysin and chromogranin. Ki-67 index is getting nod in clinical set-up for using it as essential part of pancreatic NET classification. Recognising, both endocrine and non-endocrine carcinoma components, and employing immunohistochemical studies are important for a correct diagnosis and optimal treatment for mixed endocrine exocrine carcinoma [9-11,13].

Study showed all duodenal NET was treated with endoscopic resection. Ileal resection was done in 11% of the case [34,35]. Appendicectomy done in 7% of cases, Enucleation of pancreatic NET was done in 4.2% of cases. Whipple, central pancreatectomy, right hemicolectomy, TAMIS constituted 2.1% of cases each. In our study Synaptophysin was positive in 42 (97%), focally positive in 1 (3%) of cases, whereas chromogranin was positive in 39 (90%), focally positive in 1 (3%), negative in 7% of cases. Our results were comparable to results published by Fen Yau li et al., synaptophysin was positive in 100% and chromogranin in 61.9% [36]. Similar results were found in study done by Uchiyama C et al., where synaptophysin was positive in 100% and chromogranin in 42.9% [10]. In our study, Ki-67 index <2% was 95%, Ki-67 index <5% was 5%, these results were contradictory to results published by Hatanaka Y et al., where Ki-67 <2% was 60% and Ki-67 >3% was 40% [37]. Margins were negative in 97% of patients in our study, this is in contrast with study done by Pape UF et al., were R0 resection was achieved only in 66% of patients [32].

Limitation

Although, it was first study in our region and the limitation was the sample numbers of cases used in the study however it does not impact our study as the number of sample were statistically significant and also getting such cases are not so frequent. Due to the small number study sample, statistical analysis was performed, but without significance in the clinical features of various locations in the gastrointestinal tract. An endoscopic detail of more number of cases would have given more enlightened analysis of NETs clinical profile.

Conclusion

We analysed the clinicopathological and immunohistochemical characteristics of 47 NETs. The incidence of positive immunohistochemical reactivity for synaptophysin and chromogranin was high at 97% and 90.5%, which is a significant number and can be useful in the diagnosis for NETs. Such in depth clinical details on NETs are required as its NETs have lethargic clinical courses and most of cases are asymptomatic. NETs of the GIT, known to be rare tumours; present with increased incidence over the recent decades, most probably due to the increased awareness among the physicians and improved diagnostic techniques.

Funding: This study was funded by Institutional grant.

G1=95%; G2=5%