Acne vulgaris (or simply acne) is, characterised by areas of seborrhoea (scaly red skin), comedones (blackheads and whiteheads), papules (pinheads), nodules (large papules), pimples, and possibly scarring which persist for rest of the life [1]. Aside from scarring, its main effects are psychological, such as reduced self-esteem [2] and in very extreme cases, depression or suicide [3]. Other psychological abnormalities documented are embarrassment, social inhibition, emotional distress, anxiety, etc., [4,5]. Youngsters considering acne as a purely cosmetic problem is really a worrying issue as this leads them to seek advice and treat their acne by beauticians and through cosmetic salons. This is a preferred practice rather than making a medical consultation with dermatologists and has been observed among both genders [6,7,8].

Acne as a disease profoundly affects the patients physically, socially as well as psychologically and can severely impair the quality of life in sufferers [9]. Authors have reported that patients of acne consciously avoided wearing clothes that revealed their acne affected skin [10], they avoided social gatherings due to the higher degree of social anxiety and social avoidance/withdrawal [11], they avoided swimming and other sport because of embarrassment [12]. One of the ways to reduce this psychological and social suffering of acne patients is utilising the most effective and safe treatment options for management of their disease and following up of these for response and satisfaction. For example, topical treatment with benzoyl peroxide is most effective for mild acne and only in non-responsive cases, tretinoin or adapalene can be used. Similarly, for moderate grade acne combination therapy of benzoyl peroxide, antibiotics and/or retinoid has shown the best results [13].

This remedy of using effective and safe treatment strategy has achieved a high rate of satisfaction among the patients and has shown to be effective in significantly reducing the impairment of quality of life [14]. Knowledge of patients’ beliefs, perceptions, and practices with regard to their acne is necessary for planning educational programs about their condition and in creating awareness about the availability of effective treatment. Although information on basic science, clinical features, psychosocial impact and treatment of acne is available, there is a lack of data on the knowledge and understanding by the patients about acne. Authors in their previous studies have reported that acne sufferers are not well informed about the causes and the modalities to alleviate its severity [6,15,16]. This poses an intense need for nationwide projects of health education programs in this area and easy access to appropriate information. To the best of authors’ knowledge and literature search, there was no such study conducted in India till then and hence authors planned to assess the beliefs and perceptions of acne patients regarding their condition and expectations about treatment and also analysed the association of patients’ characteristics with knowledge about acne vulgaris and association of patient characteristics with the impact of acne on their psychosocial life.

Materials and Methods

This study was a cross-sectional, observational, questionnaire based study carried out in the Dermatology OPD of a tertiary care hospital in western India from February 2015 to January 2016. The study began after getting approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee (Ref: BVDU/MC/66 dated 2/09/2014). On sample size calculation, a total of 180 acne patients were to be included considering the number of such patients per month and the visiting frequency of the investigator (twice per week). In 1956, Pillsbury, Shelley and Kligman published the earliest known grading system [17]. The grading includes the following:

Grade 1: Comedones and occasional small cysts confined to the face.

Grade 2: Comedones with occasional pustules and small cysts confined to the face.

Grade 3: Many comedones and small and large inflammatory papules and pustules, more extensive but confined to the face.

Grade 4: Many comedones and deep lesions tending to coalesce and canalize, and involving the face and the upper aspects of the trunk.

In 1958, James and Tisserand in their review of acne therapy, provided an alternative grading scheme [17]

Grade 1: Simple non-inflammatory acne - comedones and a few papules.

Grade 2: Comedones, papules and a few pustules.

Grade 3: Larger inflammatory papules, pustules and a few cysts; a more severe form involving the face, neck and upper portions of the trunk.

Grade 4: More severe, with cysts becoming confluent.

Inclusion criteria: Patients of acne vulgaris (both genders, any age) coming to the dermatology OPD for consultation and willing to give consent for participation in the study by filling the study questionnaire were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with known physical or mental illness which would impact the psychological status of the subject were excluded from the study.

Authors could include 224 patients but some of them did not fill the questionnaire completely and finally had a sample of 183 patients who consented/assented (English/Marathi) for the study and filled a pretested, pre-validated questionnaire (English/Marathi). A total of 41 subjects who did not fill in the questionnaire completely were not serious about the task to be performed and hence were not included in the study, data analysis as incomplete data would not have given appropriate results. This structured questionnaire was adapted from Tan JK et al., which was in English and was modified based on the study site and population [15]. Permission was obtained for using the modified questionnaire from Tan JK et al., [15]. The questionnaire was translated in local language, Marathi and validated by two Marathi speaking faculty from Dermatology, Pharmacology and Psychiatry departments each. Suggestions were incorporated in the questionnaire and the final version was then used for the study [Annexure]. It consisted of 20 items (19 multiple choice questions and one open-ended question)- six questions (Q 1,2,3,5,7,19) based on general information about their condition, five questions (Q 6,8,9,10,18) based on knowledge about acne and nine questions (Q 4,11-17 and 20) on perception about their condition and its treatment and its impact on their psychosocial life. The study investigator was available while filling the questionnaire to solve any queries related to the same.

Knowledge about acne in the study subjects was categorised as “Good” or “Poor” as follows: more than four questions (out of five knowledge questions) answered correctly were considered to have good knowledge and those answering less than four correct answers were considered as having poor knowledge. These two categories of study subjects (good and poor knowledge) were used for further analysis of results. The questions on perception of acne and its impact on self-image, relationship with friends and family, on work activity or school performance were evaluated on the responses selected by the subjects in the questionnaire. The grades of impact: none, minimal and moderate to severe were in the form of options to be selected for answering the questions and were subjective opinions of the participants, no scoring system was used for their analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Results were expressed in percentage or frequencies. Data were analysed using Graph-pad Prism version 6.0 Chi-square test was used for association of knowledge about acne against various patient characteristics. Authors also analysed the association of patients’ characteristics (age, gender, education, occupation, information regarding causes of acne and perception regarding prevalence of acne) and the impact of acne on their psychosocial life using chi-square test.

Results

Majority of the study subjects were below 25 years of age and were suffering from acne for more than one year. A total of >80% had Grade II acne vulgaris and >75% of the study subjects were educated to the level of graduation [Table/Fig-1].

Demographic characteristics of the study participants.

| Characteristics | No. of subjects n=183 (%) |

|---|

| Age (years) Mean (SD) 22.5 (±5.5) |

| Up to 20 | 80 (43.7) |

| 21 to 25 | 60 (32.8) |

| 26 to 30 | 22 (12.02) |

| More than 30 | 21 (11.5) |

| Gender |

| Female | 108 (59.0) |

| Male | 75 (41.0) |

| Education |

| Up to 12th grade | 39 (21.3) |

| Graduation | 135 (73.8) |

| Post-graduation | 9 (4.9) |

| Occupation |

| Students | 84 (45.9) |

| Housewife | 26 (14.2) |

| Service | 39 (21.4) |

| Professional | 3 (1.6) |

| Business | 31 (16.9) |

| Duration of acne vulgaris |

| <3 months | 69 (37.7) |

| months | 5 (2.7) |

| 6-12 months | 24 (13.1) |

| >12 months | 85 (46.4) |

| Grade of acne vulgaris |

| Grade I | 25 (13.6) |

| Grade II | 153 (83.6) |

| Grade IV | 5 (2.73) |

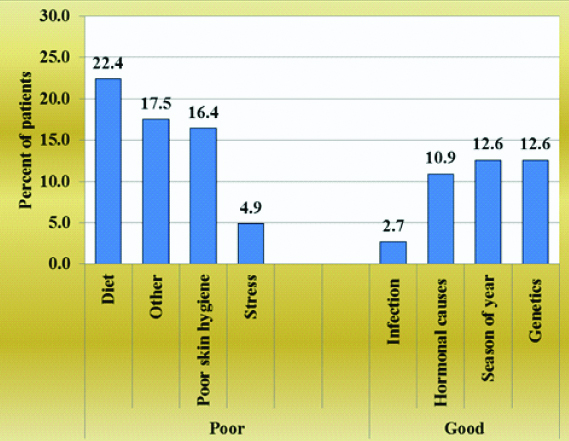

The [Table/Fig-2] shows that 61.2% patient had poor knowledge about the predisposing factors of acne as they thought that diet, using varying brands of cosmetics, poor skin hygiene and stress might be the causative factors of acne. Whereas, 38.8% of patients had appropriate knowledge and considered influence of genetics, seasons of the year, hormonal changes and infection as major causes of acne.

Patients’ knowledge about predisposing factors of acne vulgaris.

Amongst the different groups of drugs used for the treatment of acne vulgaris, most of the study subjects were aware of topical preparations (77%), antibiotics (61.2%) and medicated soaps (55.7%). A total of 78.7% of them were unaware of the use of hormonal therapy for acne vulgaris. More than 50% of the study subjects preferred topical preparations over oral for the treatment of acne where they believed that cosmetics (lotions, natural remedies, turmeric powder, Multani mitti, foundations) should be the most useful products to treat acne vulgaris [Table/Fig-3]. About 25% of them also believed in the usefulness of alternative therapy (Ayurveda, homoeopathy) in treating acne vulgaris.

Patient’s opinion about treatment options for acne vulgaris.

| Treatment | Helpful in treating acne |

|---|

| Yes | No | Don’t know |

|---|

| Antibiotics | 112 (61.2) | 46 (25.1) | 25 (13.7) |

| Hormonal therapy | 39 (21.3) | 104 (56.8) | 40 (21.9) |

| Topical preparations | 141 (77.0) | 12 (6.6) | 30 (16.4) |

| Medicated soaps | 102 (55.7) | 70 (38.3) | 11 (6.0) |

| Patients preferences for formulation of drugs for acne |

| Formulations | No. of patient | Percent |

| Topical (cream/lotion) | 95 | 51.9 |

| Tablets | 56 | 30.6 |

| No preference | 32 | 17.5 |

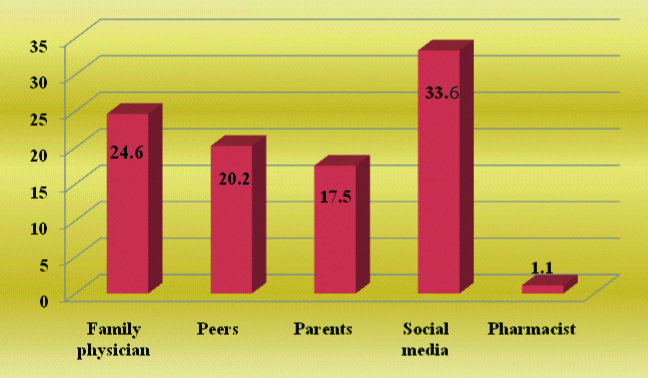

As seen in [Table/Fig-4], social media (33.6%) (Television 6.8%, magazines 5.5%, newspaper 3.3%, internet 3.8%, other modes of advertisements like radio, banners, posters 14.2%) was a common source of information about use of various products for the care of acne. A small population (3.3%) of study subjects had not used any product for managing their acne and did not fill in this question when asked. The [Table/Fig-5] shows that study subjects who were suffering from acne vulgaris for a longer duration (>6 months) before seeking medical advice had significantly (p=0.028) poor knowledge about their disease as compared to those who had it for a lesser duration. Similarly, those patients who were more influenced by social advertising media for gaining information and decision-making on their disease also had significantly (p=0.001) poor knowledge about the disease as against those who had obtained information from their physicians.

Sources of information about products used for acne vulgaris before seeking medical advice.

Association of patient characteristics with knowledge about acne vulgaris.

| Patient Characteristics | | Good (n=27) | Poor (n=156) | p-value |

|---|

| Total | No. of patients (%) | No. of patients (%) | |

|---|

| Age (years) | Up to 20 | 80 | 10 (12.5) | 70 (87.5) | 0.782 |

| 21 to 25 | 60 | 10 (16.66) | 50 (83.34) |

| 26 to 30 | 22 | 3 (13.63) | 19 (86.37) |

| More than 30 | 21 | 4 (19.04) | 17 (80.96) |

| Gender | Female | 108 | 13 (12.03) | 95 (87.97) | 0.214 |

| Male | 75 | 14 (18.66) | 61 (81.34) |

| Duration of Acne before seeking medical advice | <6 months | 93 | 19 (20.4) | 74 (79.5) | 0.028* |

| >6 months | 90 | 8 (8.88) | 82 (91.12) |

| Factor influencing patient to seek medical attention | Advertisement | 70 | 2 (2.85) | 68 (97.15) | 0.001** |

| Self-made | 64 | 15 (23.43) | 49 (76.57) |

| Friends | 18 | 3 (16.66) | 15 (83.34) |

| Parents | 31 | 7 (22.58) | 24 (77.42) |

| Grade of acne vulgaris | I | 25 | 5 (20) | 20 (80) | 0.664 |

| II | 153 | 21 (13.72) | 132 (86.28) |

| IV | 5 | 1 (20) | 4 (80) |

| Source of information about acne | Parents | 36 | 2 (5.5) | 34 (94.5) | <0.001** |

| Physicians | 35 | 15 (42.8) | 20 (57.1) |

| Friends | 31 | 3 (9.67) | 28 (90.33) |

| Advertisements | 81 | 7 (8.64) | 74 (91.35) |

Chi-square test was used to test statistical significance for differences in proportion of patients with good and poor knowledge; *statistically significant

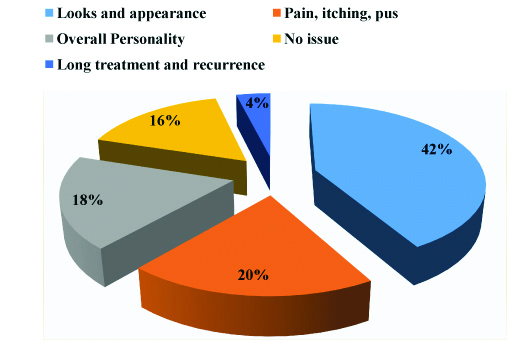

Majority of the study subjects (42%) opined that the effect of acne on their looks and appearance was the issue which bothered them the most [Table/Fig-6]. Other factors which bothered them were the pain, itching, pustular characteristics of the disease (20%) and effect on their overall personality (18%).

Issues which bothered the patients of acne vulgaris.

The [Table/Fig-7] depicts that for the majority of the study subjects, the most affected psychosocial factor due to acne vulgaris was their self-image. A total of >57% of these patients believed that the disease had a moderate to severe impact on their self-image and this was found to be statistically significant (p<0.001).

Patients’ perception about impact of acne vulgaris on their psychosocial life.

| Impact of acne on | No impact n (%) | Minimal impact n (%) | Moderate-Severe impact n (%) |

|---|

| Self-image | 6 (3.27) | 72 (39.3) | 105 (57.4)*** |

| Relationship with friends | 122 (66.6) | 22 (12.0) | 39 (21.4) |

| Relationship with family | 141 (77.0) | 10 (5.46) | 32 (17.5) |

| Work activities | 86 (47.0) | 47 (25.7) | 50 (27.3) |

| Performance at school | 127 (69.4) | 12 (6.6) | 44 (24) |

Chi-square test was used to analyse the severity of impact of acne vulgaris on various aspects of psychosocial life in the study participants; ***p<0.001

The [Table/Fig-8] shows that there was a statistically significant association (p=0.002) between the study subjects who had poor information about the causes of acne vulgaris and the impact (moderate to severe) this disease had on their psychosocial life. There was also a significant association (p=0.031) between patients’ perception about the prevalence of acne vulgaris and the psychosocial impact of the disease on them. It was found that the subjects who believed that the prevalence of acne vulgaris is very high in the general population (i.e., 51-75% or 75-100%) had least impact of this condition on their psychosocial life.

Association of acne vulgaris patients’ characteristics with psychosocial impact.

| Patients’ Characteristics | No impact (n=77) | Minimal impact (n=68) | Moderate to severe impact (n=38) | p-value |

|---|

| No. of patients (%) | No. of patients (%) | No. of patients (%) | |

|---|

| Age (years) |

| Up to 20 | 35 (43.75) | 28 (35.00) | 17 (21.25) | 0.288 |

| 21 to 25 | 23 (38.33) | 24 (40) | 13 (21.66) |

| 26 to 30 | 6 (27.27) | 12 (54.54) | 4 (18.18) |

| More than 30 | 13 (61.90) | 4 (19.09) | 4 (19.09) |

| Gender |

| Female | 45 (41.66) | 40 (37.03) | 23 (21.29) | 0.977 |

| Male | 32 (42.66) | 28 (37.33) | 15 (20) |

| Education |

| Up to 12th grade | 14 (36.84) | 17 (44.73) | 7 (18.42) | 0.794 |

| Graduation | 59 (43.38) | 47 (34.55) | 30 (22.05) |

| Post-graduation | 4 (44.44) | 4 (44.44) | 1 (11.11) |

| Occupation |

| Students | 36 (42.85) | 30 (35.71) | 18 (21.42) | 0.926 |

| Housewife | 10 (45.45) | 9 (40.90) | 3 (13.63) |

| Business/professional/service | 31 (40.25) | 29 (37.66) | 17 (22.07) |

| Information about causes of acne vulgaris |

| Good | 10 (12.98) | 17 (25) | 0 (0) | 0.002** |

| Poor | 67 (87.02) | 51 (75) | 38 (100) |

| Perception regarding prevalence of acne vulgaris |

| 0 to 25 % | 6 (25.00) | 9 (37.50) | 9 (37.50) | 0.031* |

| 26 to 50 % | 19 (35.84) | 19 (35.84) | 15 (28.30) |

| 51 to 75 % | 43 (46.23) | 36 (38.70) | 14 (15.05) |

| 75 to 100% | 9 (69.23) | 4 (30.76) | 0 (0) |

Chi-square test was used to test statistical significance for differences in proportion of patients with various grades of impact on their psychosocial life; *statistically significant

Discussion

Acne vulgaris, a chronic inflammatory skin disease affects 80% of adolescents and adults at some age. Early and aggressive treatment has been advised to lessen the overall long-term psychosocial and cosmetic impact to these individuals [2]. In the present study, <40% of patients had adequate information about acne vulgaris and its causes [Table/Fig-2]. These subjects selected one of the predisposing factors which have a higher strength of association with acne vulgaris-genetic influence, seasonal occurrence in the year, hormonal changes and infection. Most of these factors are known but recently genetic influence has been incorporated in the causality of acne [18]. Genome-wide association study by Navarini AA et al., has identified three novel susceptibility loci for severe acne vulgaris and their data supports a key role for dysregulation of TGFβ-mediated signalling in susceptibility to acne [19].

A total of >60% of patients in the present study had inadequate information and considered influence of diet, poor skin hygiene, stress and using varying brands of cosmetics as the important predisposing factors for acne vulgaris. These factors are found to be influencing acne but supposed to have a low strength of association with acne vulgaris [18]. In a review article on the relationship of diet and acne, Pappas A, has concluded that to date research does not prove that diet causes acne but rather influences it to some degree which is still difficult to quantify [20].

The present study participants (around 82%) revealed the use of cosmetic products and alternative therapy which they believed were the most useful treatments for acne vulgaris. The common source of information regarding these was social media (33.6%) [Table/Fig-4]; magazines in female subjects, whereas newspapers and internet in males. Television as a source of information was common to both. This reveals the pattern of social networking in the Indian scenario. In a study done by Tan JK et al., in Canada, female patients were more likely to obtain this information from magazines, newspapers, aestheticians, and family physicians; while male patients more frequently obtained information from parents and pharmacists [15].

In this study, authors have tried to associate the knowledge of study participants about acne vulgaris with various parameters as shown in [Table/Fig-5]. Even on the extensive literature search, authors were not able to find any such study conducted in India or abroad for comparison with the present study results. In the present study, patients suffering from acne vulgaris for >6 months’ duration before seeking medical advice were found to have statistically significant (p=0.028) poor knowledge about their disease. Due to poor knowledge about their disease, they might have neglected the condition and delayed their approach to the dermatologist for consultation about treatment. Also, those patients who were more influenced by social media for gaining information about acne vulgaris and decision-making to seek medical advice had significantly (p=0.001) poor knowledge about their condition. This may suggest the role of social media as an incomplete source of information which promotes or advertises only the lucrative aspect and not the drawbacks of its product of advertisement.

Majority of this study subjects opined that their looks and appearance due to acne bothered them the most [Table/Fig-6]. Some of them also felt that it affected their overall personality negatively. It has been found that poor physical appearance leads to a lowered opinion by others, which logically leads to lower popularity, and, “Lack of popularity may undermine self-esteem and self-confidence” [21,22]. Many acne patients have problems with self-image and interpersonal relationships aggravated by teasing or taunting, other’s scrutiny and the feeling of being on display [21]. They usually experience embarrassment, social anxiety and general avoidance of activities that bring attention to their condition [22]. Authors observed a similar situation in the present study subjects, where the effect of acne on self-image appeared to be most sensitive indicator of psychosocial impact and this was statistically significant (p<0.001) [Table/Fig-7]. Studies were done by Tan JK et al., Tallab TM, Shuster S et al, Wu SF et al., also report the same fact where self-image was the most affected psychosocial factor [15,16,23,24]. Hazarika N et al., has conducted a similar study in Tamil Nadu, India, using the DLQI questionnaire to grade the QoL of acne patients and has found a significant impact of acne on emotions, daily and social activities, study/work, and also interpersonal relationships [25]. In the present study, the psychosocial impact of acne did not differ among subjects of both the genders while there was less impact of acne among housewives as compared to students and professionals suffering from the disease. This might be explained by the fact that housewives do not socialise daily to that extent nor they have an academic or professional routine which might interfere with their psychological behaviour [Table/Fig-7].

In this study, authors analysed the data for the association between the psychosocial impact of acne with patients’ characteristics (age, gender, education, occupation, knowledge and their perception about the prevalence of acne in society). Studies have revealed the burden of acne to diminish adolescents’ Quality of Life (QoL) and to impact their global self-esteem [26,27]. The present study also demonstrates that the effect of acne on the psychosocial impact of the subjects decreased with the increasing age and better educational level, although these results were not statistically significant, but this trend is clearly visible [Table/Fig-8]. The lack of significance might be due to less number of subjects in the age-wise and education-wise subgroups of the present study.

The present study results also show that there was a statistically significant (p=0.002) association between psychosocial impact and knowledge about the disease acne vulgaris. Study subjects who had poor information about acne vulgaris had a moderate to severe impact on their psychosocial life. A significant association (p=0.031) was seen amongst the subjects who perceived the prevalence of acne vulgaris to be very high (51-75% or 75-100%) and the psychosocial impact of the disease on their life. These subjects were minimally affected by their condition and authors perceive that they did not bother about it psychologically or socially considering it a common disease.

Limitation

This study did not directly assess clinical depression or use any QoL questionnaire to evaluate the effect of acne on psychosocial life of the present subjects. This can be a future study which can help to plan awareness program for such individuals. The inferences drawn about the impact of acne on the psychosocial life of study subjects are based on the questions in the questionnaire and no scoring system has been used to evaluate them. The responses of subjects have been directly accepted and presented as the results of this study.

Conclusion

Patients of acne vulgaris in the study set-up lacked adequate knowledge about the disease and its treatment. Acne had a significant impact on the participants’ psychosocial life, especially their self-image. A significant association was found between poor knowledge about the disease with the long duration of acne and the influence of social media on decision making of their disease. The study indicates a need for educating the teenage population about the causes, predisposing factors, curability and treatment options available for acne vulgaris before they get affected by acne vulgaris. Social media should be effectively involved in this process as it was found to be the commonest source of obtaining information among the study population. Psychological counselling about curability and patience during the study period should be provided to all patients by treating dermatologists or general practitioners. Patient information charts and leaflets can also be adapted as a means of education for these patients.

Chi-square test was used to test statistical significance for differences in proportion of patients with good and poor knowledge; *statistically significant

Chi-square test was used to analyse the severity of impact of acne vulgaris on various aspects of psychosocial life in the study participants; ***p<0.001

Chi-square test was used to test statistical significance for differences in proportion of patients with various grades of impact on their psychosocial life; *statistically significant