Retrosternal Goitre-An Anaesthetic Challenge

Shaila S Kamath1, Shilpa A Naik2, NP Pratiksha3

1 Professor and Head, Department of Anaesthesiology, Kasturba Medical College, Mangalore, Karnataka, India.

2 Assistant Professor, Department of Anaesthesiology, Kasturba Medical College, Mangalore, Karnataka, India.

3 Junior Resident, Department of Anaesthesiology, Kasturba Medical College, Mangalore, Karnataka, India.

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr. Shilpa A Naik, Dhruva Residency, Yekkur, Near Fisheries College, Mangalore-575002, Karnataka, India.

E-mail: shilpa8c@gmail.com

Airway management of patients undergoing thyroidectomy for Retrosternal Goitre (RSG) poses a unique challenge. Associated co-morbidities, manipulation of the airway by the surgeons, airway compromise during induction, intubation, intraoperative and post-operative period can contribute to adverse events. We describe anaesthetic management of a patient with long standing goitre for 61 years with retrosternal extension with tracheal narrowing and compression for thyroidectomy. We secured the airway in an awake, spontaneously breathing patient under topical anaesthesia and sedation using direct laryngoscopy.

Airway management of RSG is challenging at every phase of anaesthesia. Maintaining airway patency, vigilance and preparedness are keys to the success of intubation.

Awake intubation, Difficult intubation, Tracheal narrowing, Tracheomalacia

Case Report

A 77-year-old female, weighing 55 kg, height 161 cm and BMI of 21.21 presented with history of dry cough, breathlessness on exertion since five months, with history of swelling in the anterior aspect of neck, since 61 years. She was a hypertensive on amlong 5 mg OD and atenolol 50 mg OD and a known hyperthyroid, on neomercazole 5 mg OD since a month. There was no history of orthopnoea, stridor or change in voice.

On examination, the swelling was on the anterior aspect of neck extending beyond anterior border of right sternocleidomastoid muscle, superiorly, upto hyoid and 2 cm medial to anterior border of left sternocleidomastoid [Table/Fig-1]. The swelling was firm in consistency and moved with deglutition. Getting below the swelling was not possible, with positive Pemberton’s sign. On airway examination, she was edentulous with adequate mouth opening, Mallampati class 2. Neck movements were restricted both in flexion and extension with normal side to side movements. Indirect laryngoscopy revealed mobile bilateral vocal cords during phonation and respiration.

Figure showing enlarged mass on the anterior aspect of neck.

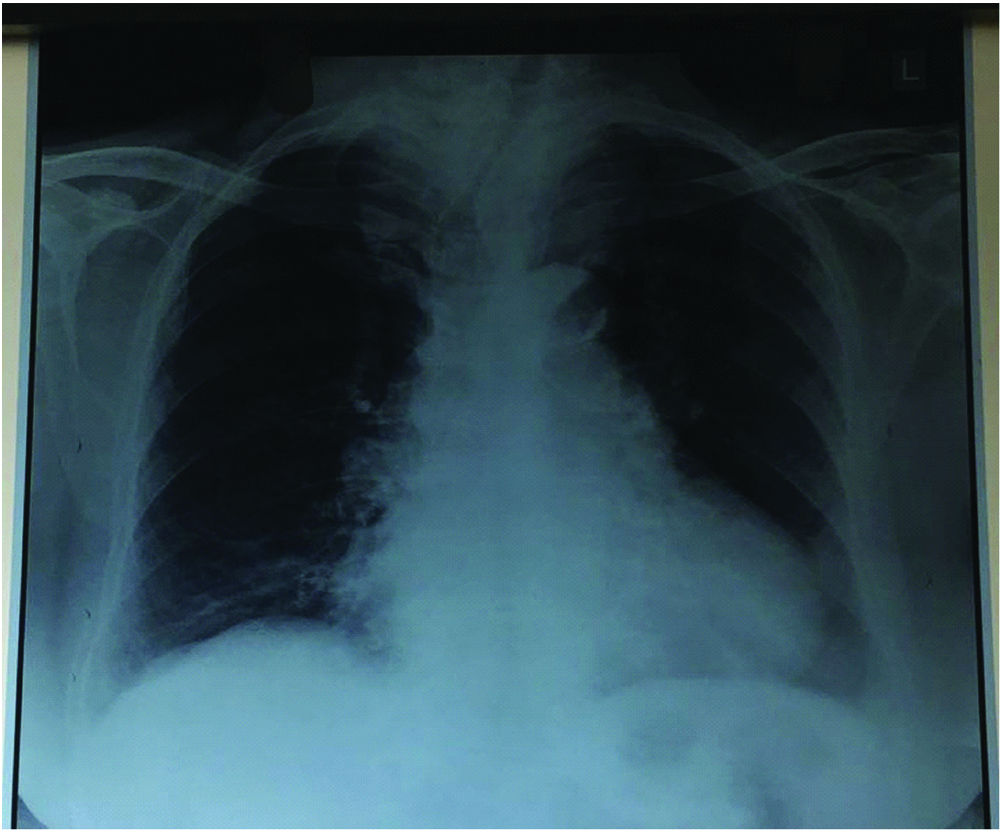

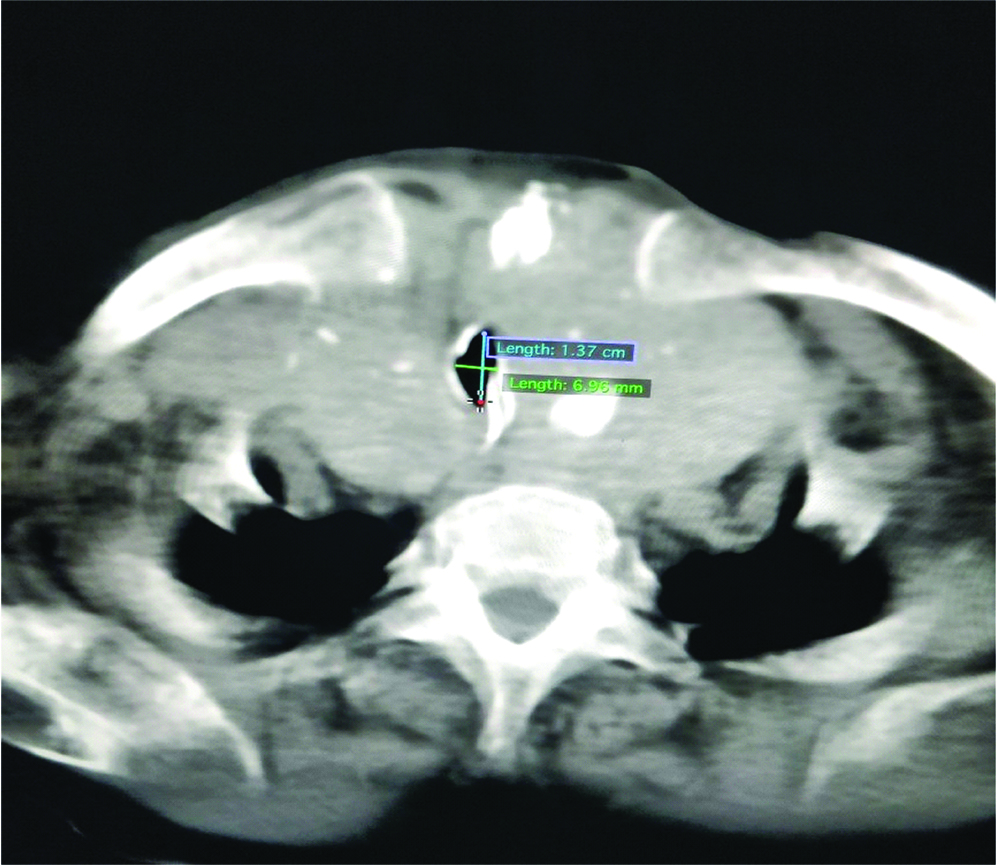

On examination, vitals were stable with PR-70/min, BP-140/90 mm Hg, SpO2 of 100%. Baseline investigations were within normal limits with Hb-10.9 mg/dL and low calcium 7.3 mg/dL. Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed complete right bundle branch block with normal Echocardiography (ECHO) study. Thyroid profile showed low TSH-0.011 IU/mL with normal T3, T4 values. Chest radiograph showed narrowed and deviated trachea with widening of superior mediastinum [Table/Fig-2]. Computed Tomography (CT) neck showed thyroid gland with heterogeneous enhancement with areas of necrosis and calcifications within the gland. The right lobe measured 10.8x5.5 cm and left lobe measured 8.9x5 cm. Inferiorly left lobe was seen extending into retrosternal area. Superiorly, the right lobe was extending upto C2 vertebra. Medially the lesion was compressing trachea with significant narrowing of air column with subglottic diameter of 6.2 mm [Table/Fig-3]. Upper trachea was displaced to left side. The lesion was abutting thyroid, cricoid cartilages and inferiorly arch of aorta. Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology (FNAC) report was consistent with benign follicular nodule.

Figure showing AP view chest X-ray of narrowed and deviated trachea.

CT scan of neck showing narrowed trachea.

The patient was explained and reassured for keeping her awake during intubation. A written informed consent was obtained for awake intubation, flexible fibreopticscopy and post-operative mechanical ventilation. On the day of surgery the operating room was equipped with difficult intubation cart. Patient was fasting for eight hours. In the preoperative room, a wide bore cannula was secured. Inj. glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg IV was given. Patient was nebulised with 2 mL of 2% lignocaine and 2% viscous lignocaine gargling 20 minutes prior to shifting to Operating Room (OR). Cardiothoracic surgical team was on standby.

After shifted to OR, standard monitors were connected, PR-100/ min, BP-180/100 mm Hg, saturation of 100% on room air. Patient was oxygenated continuously through nasal prongs at 4L O2/min. Inj. fentanyl 25 mcg IV and Inj. midazolam 0.5 mg IV was given. Inj. esmolol 20 mg IV was given to prevent haemodynamic response to intubation. Awake intubation with direct laryngoscopy was attempted with minimum external laryngeal manipulation showing Cormack Lehane 3 and intubated with 7.0 mm armour tube. Tube placement was confirmed by equal air entry on auscultation and ETCO2. Patient was induced using Sevoflurane 6% and NMB achieved with Inj. rocuronium 50 mg IV. Left radial artery was cannulated. Intraoperatively maintained with O2:N2O 1:1 and sevoflurane 1%, fentanyl 25 mcg/hr and vecuronium 1 mg sos. Retrosternal part of the thyroid was removed intact without the need of sternotomy [Table/Fig-4]. Patient was haemodynamically stable intraopertively. Following completion of surgery when patient was conscious and breathing spontaneously reversed using Inj.neostigmine 3.0 mg IV and Inj. glycopyrrolate 0.6 mg IV. Anticipating tracheomalacia due to long duration of mass, patient was shifted to post-operative ICU on tracheal tube with T piece @4L O2/min and Inj. fentanyl 20 mcg/hr IV infusion.

Figure showing specimen of thyroid gland.

Leak test was done the next morning. Patient was extubated over a tube exchanger and kept on Hudson mask @4L O2/min. Post-operative recovery was impeccable without respiratory compromise.

Discussion

Thyroid disorders are one of the most ubiquitous and well represented endocrine diseases around the globe. Anaesthesiologists face rarely yet certainly an uphill task and a demanding situation in handful of cases. RSG though rare is one such entity posing a formidable challenge due to acute cardiorespiratory decompensation following induction of anaesthesia [1]. Difficulties can be encountered while securing airway, surgical manipulation and extubation. Any goitre which descends below the plane of thoracic inlet or grows into the anterior mediastinum for more than 2 cm is considered RSG.

The challenges associated with mediastinal mass like long standing RSG are difficult intubation, cardiovascular compromise during manipulation of gland, blood loss, long duration of surgery and post-operative tracheomalacia [2,3]. A detailed pre anaesthetic assessment of symptoms, airway assessment, blood profile and imaging studies are the cornerstones for the anaesthetic management [4]. Winning the patients confidence and cooperation adds to the success of awake intubation [5]. Maintaining continuous patent airway and adequate gas exchange is of prime importance to prevent mortality and morbidity. According to Huins and colleagues classification of RSG our patient falls into grade1 with goitre above aortic arch [6]. As per classification of Mediastinal Mass Syndrome (MMS) by Erdos and Tzanova our patient belongs to grade 2 ‘uncertain’ type with history of breathlessness and CT evidence of tracheal compression [7]. The incidence of difficult intubation with thyroid swellings is 2-12.7% and that of failed intubation is 0.3-0.5% [4,8,9].

A preformulated plan and backup modalities were in place before taking the patient for surgery. Airway access to this patient was established by awake direct laryngoscopy under topical anaesthesia due to its inherent safety [5]. Negative intrapleural pressure is preserved during spontaneous breathing maintaining the airway diameter [7]. Awake intubation maintains natural airway, spontaneous ventilation, protects from risk of reflux [10]. Considering the size and duration of the mass, to prevent loss of airway we opted for direct laryngoscopic awake intubation under topical anaesthesia as plan A to flexible fibreopticscopy. This is explained by the evidence that there have been circumstances that following failed awake fibreoptic intubation, subsequent direct laryngoscopic intubation has been a success. Using awake fibreoptic intubation in an already narrowed trachea and obstructive symptoms can result in “cork in bottle” situation [4,11,12].

Regional anaesthesia with airway blocks, cricothyrotomy/tracheostomy was not feasible due to anatomical restrictions caused by the goitre. Sedation could have resulted in further deterioration of airway and hence was not part of the plan. Patients undergoing thyroidectomy for RSG requiring surgical access other than standard collar incision number around 2% [13]. Mediastinal mass syndrome can occur at every stage of anaesthesia up to post-operative period or simply by changing position. Surgical manipulation can cause compression of trachea causing difficult ventilation [3].

Tracheal deviation and compression resolves completely after thyroidectomy. Nevertheless tracheomalacia should be anticipated in a long standing goitre. Literature states that tracheomalacia is almost mythical in modern thyroid surgery in the west [6,14]. Plan to extubate next day was based on the amalgamation of history of long standing goitre, retrosternal extension and severely stenosed trachea. A tailored approach should be followed for every case regarding retention of tube based on the preoperative and intraoperative findings.

Conclusion

We believe that awake direct laryngoscopic intubation under topical anaesthesia in experienced hands can be considered in patients with huge RSG. Difficult airway should be foreseen. Good communication, psychological and pharmacological preparation of the patient can be crucial to the success of awake intubation. A tailored approach keeping in mind the comorbidities and clinical status should be the primary principle.

[1]. Dhanpal RD, Shivappagoudar VM, Gonsalvez G, Vithayathil R, Alappat AM, Anaesthetic management of a patient with retrosternal goiter using a double-lumen endotracheal tubeKarnataka Anaesth J 2017 3:13-15. [Google Scholar]

[2]. Nakra D, Puri GD, Anaesthetic management of retrosternal goiterJ Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2005 21:309-11. [Google Scholar]

[3]. Farling PA, Thyroid diseaseBr J Anaesth 2000 85(1):15-28.10.1093/bja/85.1.1510927992 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[4]. Wong P, Haw Chieh Liew G, Kothandan H, Anaesthesia for goitre surgery: A reviewProceedings of Singapore Health Care 2015 24(3):165-70.10.1177/2010105815596095 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[5]. Ramkumar V, Preparation of the patient and the airway for awake intubationIndian J Anaesth 2011 55:442-47.10.4103/0019-5049.8986322174458 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[6]. Dempsey GA, Snell JA, Coathup R, Jones TM, Anaesthesia for massive retrosternal thyroidectomy in a tertiary referral centreBr J Anaesth 2013 111(4):594-99.10.1093/bja/aet15123690528 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[7]. Tan PCS, Esa N, Anaesthesia for massive retrosternal goiter with severe intrathoracic tracheal narrowing: the challenges imposed-A case reportKorean Journal of Anaesthesiology 2012 62(5):474-78.10.4097/kjae.2012.62.5.47422679546 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[8]. Randolph GW, Shin JJ, Grillo HC, Mathisen D, Katlic MR, Kamani D, The surgical management of goiter: Part II. Surgical treatment and resultsLaryngoscope 2011 121(1):68-76.10.1002/lary.2109121154775 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9]. Chaves A, Carvalho S, Botelho M, Difficult endotracheal intubation in thyroid surgery: A retrospective studyInternet J Anaesthesiol 2009 22(1)10.5580/12c0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[10]. Benumof JL, Hagberg CA, Benumofs and Hagbergs airway management 2013 3rd editionPhiladelphiaElsevier/Saunders:243-264. [Google Scholar]

[11]. El-Dawlatly A, Takrouri M, Elbakry A, Ashour M, Kattan K, Hajjar W, Perioperative management of huge goiter with compromised airwayInternet J Anaesthesiol [Internet] 2002 7(2)10.5580/1a8 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[12]. Tripathy DK, Ravishankar M, Airway management in a case of severe tracheal narrowing by retrosternal goiter - A case reportInternet J Anaesthesiol [Internet] 2009 23(2)10.5580/2884 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[13]. Rodrigues J, Furtado R, Ramani A, Mitta N, Kudchadkar S, Falari S, A rare instance of retrosternal goitre presenting with obstructive sleep apnoea in a middle-aged personInternational Journal of Surgery Case Reports 2013 4(12):1064-66.10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.07.04024212758 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[14]. Findlay JM, Sadler GP, Bridge H, Mihai R, Post-thyroidectomy tracheomalacia: Minimal risk despite significant tracheal compressionBr J Anaesth 2011 106:903-06.10.1093/bja/aer06221450708 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]