Mass gatherings were defined as a high number of persons (exceeding 25,000 people) at a specific location for a specific purpose (political, cultural, artistic, sports, and religious) for a defined period of time [1]. Nowadays it is explained as the specified number of persons that are attending a gathering which is enough to strain the planning, preparedness, and the response resources of community, state or nation hosting the event [2].

Mass gatherings can attract hundreds to millions of people from around the world [3]. One of the major concerns in mass gatherings is infectious diseases spread among the participants in host countries and even globally such as the global outbreak of cholera in the 19th century [4]. Despite effective and advanced public health system, communicable diseases in mass gatherings are challenging [4,5]. Increased likelihood of spread of contagious diseases can have negative socioeconomic consequences at mass gatherings [5]. Some factors that lead to infectious diseases in mass gatherings include: crowded accommodations, inadequate standards of hygiene, water shortage [2,6,7], National, regional and cultural diversity of pilgrims [8] variation in age, gender, health status of the origin country, access to advanced healthcare [9], susceptibility to illness, health complexities, and environmental and climate change [9,10]. Based on the type and location of the event, common infectious diseases are different. As an example, infectious respiratory and digestive diseases are common in terms of the type in religious gatherings [7-9,11]. Annually, a great number of religious mass gatherings are held around the world for which planners and policymakers should be aware [1] which will help in mitigating the potential risk factors that prevent the spread of infectious diseases [12]. The present study aimed to investigate the communicable diseases pattern in religious mass gatherings. The findings of the review can help health policymakers for effective health preparedness, as well as reduce the risk of communicable diseases spread during religious mass gatherings.

Materials and Methods

A systematic search of the databases for relevant studies was conducted between June 24, 1979, to July 8, 2017. The search was updated in March 1, 2018.

Inclusion Criteria

All studies conducted on religious mass gatherings consist of the cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies irrespective of language, nationality, race, religion, and time. In addition, authors obtained other relevant studies with the help of the resources of the original studies.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies on non-religious gathering such as for art, sports, and political were excluded and articles which did not have access to the full text were removed. Also, qualitative studies, letters, articles presented at seminars and editorial articles were excluded.

At the first stage of the study selection process, the reviewers read the titles and abstracts. Articles were excluded if they were not related to the research objectives.

Data Sources and Search Strategy

The main bibliographic databases were PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Cochrane. To obtain the most comprehensive and efficient results, authors searched the data sources using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms, Emtree, and related keywords (mass gathering, crowding, communicable disease, infectious disease, Hajj, Kumbh Mela, Arbaeen). The topic search terms used for searching the databases are listed below:

#1: “mass gathering” or “crowding”

#2: “communicable disease” or “infectious disease”

#3: “Hajj” or “Kumbh Mela” or “Arbaeen”

#4: #1 AND #2 AND #3

Quality Assessment and Data Extraction

In the second stage, the full text of the included articles were reviewed for quality assessment and data extraction by two independent reviewers (AK and ZG). In cases of difference between reviewers, the third reviewer (DK) clarified the discrepancy.

For quality assessment of included articles, authors used Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) for included items in reports of observational studies such as cross-sectional, cohort and case-control studies. Data extraction sheet was designed including two main parts; study characteristics and extracted data. The study characteristics sheet includes first author’s name, year of publication, country, study design (cohort, case-control, cross-sectional). The study extracted data sheet includes sample size, type of disease, age and sex of pilgrims, and concluding statement.

Results

Search Results

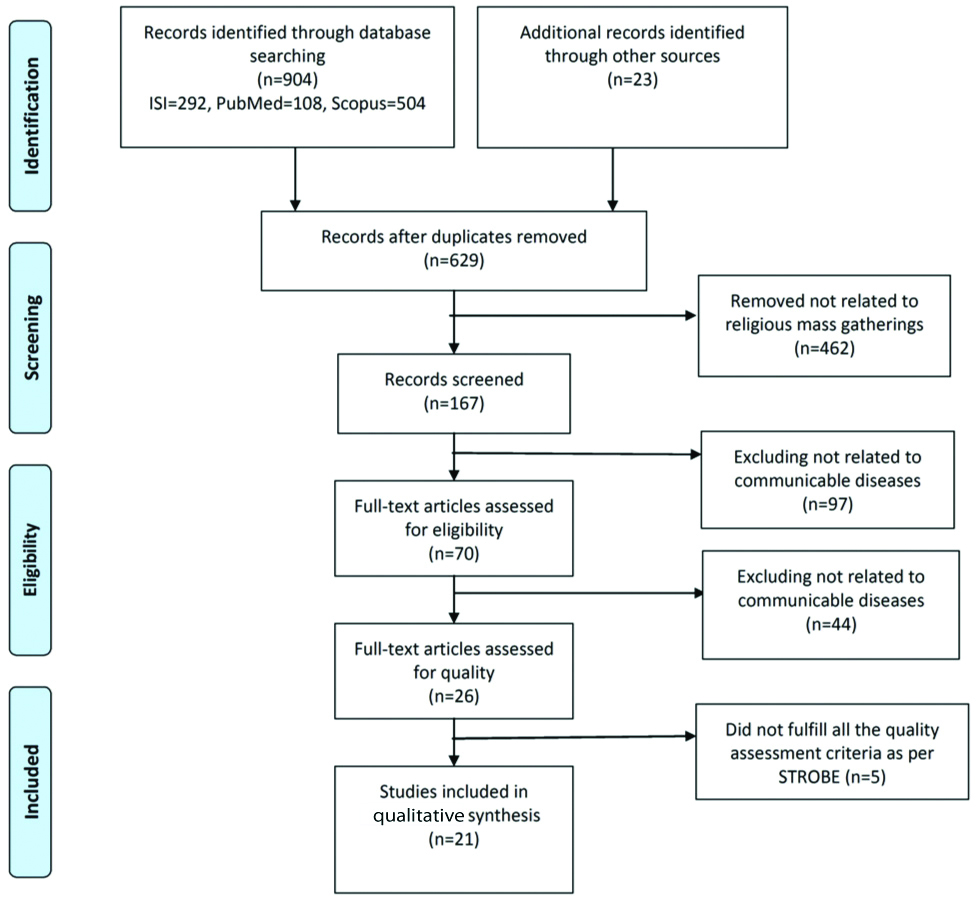

A total of 904 articles were identified in the searching database and 23 additional articles were found through the manual searching. Of 927 articles, authors rejected 213 duplicate articles during initial screening and 85 duplicate articles were rejected manually. The remaining 629 articles were reviewed on the basis of title for relevance to the review. Authors excluded 462 studies that did not meet inclusion criteria such as non-religious mass gatherings and an absence of original data. Of the residual 167 articles, after reviewing abstract and full-text, 97 and 44 articles, in total 141, articles that were not related to communicable diseases were excluded respectively. The remaining 21 papers with inclusion criteria entered qualitative synthesis [Table/Fig-1]. All 21 articles were included in the qualitative synthesis of the systematic review. According to the results, pilgrims in religious mass gatherings were often adults and include both sexes. All the age groups participants participated in the religious mass gatherings, however, most of the participants were in the 40-60-year-age group. Out of 21 articles, 15 articles were the cross-sectional studies [13-27], four articles were the cohort studies [28-31], one article was descriptive cross-sectional [32], and 1 of the 21 articles was nested case-control [Table/Fig-2] [33]. Of 21 papers, 19 articles were about respiratory infection [13-26,28,30-33], one articles about gastrointestinal infection [29], and one article about meningococcal meningitis [27]. In 10 of these articles vaccination was also studied [14-16,19,21,22,27,28,30,33]. The search results are illustrated in [Table/Fig-3].

Summary of review process on communicable diseases pattern in religious mass gatherings (number of articles).

Types of study designs on communicable diseases pattern in religious mass gatherings.

| Types of study designs | No. |

|---|

| Cross-sectional | 16 |

| Cohort | 4 |

| Nested case control | 1 |

| Total | 21 |

Categorisation of the published articles of communicable diseases pattern in religious mass gatherings upto March 2018.

| No | Study, publication year; country | Study design | Sample size | Age of pilgrims | Pilgrims sex | Kind of disease | Concluding statement |

|---|

| 1 | Ashshi A et al., [13], (2014), Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | 1600 | ≤40>40 | Male=603Female=997 | Respiratory infection (Influenza) | Active surveillance of Hajj pilgrims |

| 2 | Alqahtani A et al., [14], (2016), Australia | Cross-sectional | 356 | 18-79 | Male=213Female=143 | Respiratory infection (Influenza) | Increasing the pilgrims’ awareness of preventive measuresVaccination |

| 3 | Balkhy HH et al., [15], (2004), Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | 500 | 0-50 | Male=264Female=236 | Respiratory infection (Influenza) | Training pilgrimsVaccination |

| 4 | Barasheed O et al., [16], (2014), Australia | Cross-sectional | 966 | 7-86 | Male=568Female=398 | Respiratory infection (Influenza) | Vaccination |

| 5 | Gautret P et al., [17], (2011), France | Cross-sectional | 274 | 23-83 | Male=137Female=137 | Respiratory infection (Influenza) | Surgical face masks and N95 mask usePre-travel consultation |

| 6 | Razavi S M, et al., [18], (2013), Iran | Cross-sectional | 254,823 | 15-95 | Male=129960Female=124863 | Respiratory infection (Influenza) | Using preventive measuresEasy access to health information via Health managers’ |

| 7 | Alfelali M et al., [19], (2015), UK, Saudi Arabia, Australia | Cross-sectional | 33,213 | 0.5-95 | Male=20592Female=12621 | Respiratory infection (Influenza) | Vaccination |

| 8 | Annan A et al., [20], (2015), Ghana | Cross sectional | 839 | 21-85 | Male=383Female=456 | Respiratory infection | Face mask wearing |

| 9 | Hashim S et al., [21], (2016), Malaysia | Cross-sectional | 468 | 17-84 | Male=263Female=205 | Respiratory infection (Influenza) | Using preventive measures |

| 10 | Moattari A et al., [22], (2012), Iran | Cross-sectional | 275 | 20-70 | Male=140Female=135 | Respiratory infection (Influenza) | VaccinationPreventive measures against influenzaSurveillance of influenza |

| 11 | Memish Z A, et al., [23], (2014), Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | 38 | 25-83 | Male=26Female=12 | Respiratory infection (Influenza) and (Pneumonia) | Health education to pilgrims |

| 12 | Memish Z A et al., [24], (2015), Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | 3203 | 18-101 | Male= 1185Female= 2018 | Respiratory infection (Pneumonia) | Hand hygiene |

| 13 | Wilder-Smith A et al., [25], (2005), Singapore | Cross-sectional | 357 | 18-75 | Male=139Female=218 | Respiratory infection (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) | Surveillance of MERS-CoV* |

| 14 | Bakhsh A R et al., [26], (2015), Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | 1008 | 1->90 | Male=554Female=454 | Respiratory infection | VaccinationPre-Hajj health assessment |

| 15 | Al-Mazrou Y Y et al., [27], (2004), Saudi Arabia | Cross sectional | 729 | <2- >15 | Not mentioned | Meningococcal meningitis | Vaccination |

| 16 | Memish Z A et al., [28], (2015), Saudi Arabia | Paired cohort/non paired cohort | 1206 | 18-88 | Male=796Female=410 | Respiratory infection (Influenza) | Using preventive measures |

| 17 | Olaitan A O et al., [29], (2015), France | Cohort | 129 | - | Not mentioned | GI-Infection | Control and supervision of food distribution centers |

| 18 | Benkouiten S et al., [30], (2014), France | Cohort | 169 | 20->80 | Not mentioned | Respiratory infection (Influenza) | Improvement of public health surveillance |

| 19 | Mandourah Y et al., [31], (2012), Saudi Arabia | Cohort | 452 | 30-80 | Male=292Female=160 | Respiratory infection (Pneumonia) | Increased efforts at prevention for pilgrim risk prior to HajjAttention to spatial and physical crowding during Hajj |

| 20 | Alzahrani A G et al., [32], (2012), Saudi Arabia | Descriptive cross sectional | 4136 | 0- >65 | Male=2924Female=1212 | Respiratory infection | Strengthening the supervision for the accurate assessment of patterns of illnessesDistributing the statistical results to policy makers for better managementReporting the patient disease patterns to produce the optimal information about the health services delivered during the Hajj seasons |

| 21 | Al-Asmary S et al., [33], (2007), Saudi Arabia | Nested case-control | 250 | ≤30>40 | Male=218Female=32 | Respiratory infection (Influenza) | Vaccination |

* MERS-CoV (The Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus)

Respiratory Infection

The majority of studies (n=19; 90.48%) include the respiratory infections in mass gatherings [13-26,28,30-33]. Of these articles, 11 articles were about influenza and the importance of vaccination [13-15,17-19,21-23,28,33], three articles about pneumonia [23,24,31], and one article were about Mycobacterium tuberculosis [25].

Gastrointestinal Infection

One article was about Salmonella [29]. Salmonella persisted in the pilgrims’ stools.

Meningococcal Meningitis

One article was about Meningococcal meningitis. Age and sero group W135 were effective factors in the incidence of meningococcal meningitis [27].

The results of this study indicated that epidemiological monitoring can determine the vaccination policy.

Discussion

According to the majority of studies, respiratory infections are the most prevalent among pilgrims of mass gatherings. Among the reported respiratory diseases, the most frequent is influenza disease [34]. In a study conducted among Malaysian pilgrims in 2013 Hajj, the prevalence of the respiratory disease was 93.4% with a subset of 78.2% for Influenza-Like Illness (ILI) [21]. Balkhy HH et al., report a high incidence of influenza as a cause of upper respiratory tract infection among Hajj pilgrims. This study aimed to investigate the most common respiratory viruses among pilgrims of Hajj [15]. The study of Shah Murtaza Rashid revealed that respiratory tract infections such as influenza and pneumonia were 73.33% at Hajj. The findings of this study also showed a high incidence of influenza among pilgrims. Although the disease is preventable through the vaccine, only 4.7% of the pilgrims received the vaccine [35].

Therefore, it seems that the type and nature of mass gatherings are important in the risk of influenza transmission [19,30]. Environmental pollution, reduced personal hygiene, overcrowding and intense congestion are factors that transmit disease in mass gatherings [14,18,19]. The global transmission of this disease is one of the concerns of public health due to the return of pilgrims to their country [14,33,36]. Accordingly, the religious mass gatherings planners should pay attention towards preventable infectious diseases, so that they can prepare a vaccine before the ceremony and recommend pilgrims.

Another respiratory infection among pilgrims is pneumonia. Pneumonia as one of the life-threatening diseases is a major health problem particularly among the elderly pilgrims [31]. Accordingly, pneumonia and influenza have been one of the most common diseases among the Hajj pilgrims and even one of the causes of death among Iranian pilgrims in Hajj [26]. Non-pharmaceutical interventions such as vaccine uptake, pre-travel advice seeking, hand hygiene, and increase risk perception of diseases are the ways of preventing the diseases. However, some pilgrims do not receive the vaccine. The reasons for not receiving vaccine include the belief of pilgrims about low possibility of the incidence of influenza and confidence in natural immunity against the flu [24]. Some studies believe that vaccination and facial masks are not proactive and did not significantly decrease respiratory symptoms [25,27]. According to the study of Memish ZA et al., with the aim of evaluation pneumococcal nasopharyngeal carriage prevalence among pilgrims at Hajj, pneumococcal carriage prevalence was 6.0% [24]. The incidence of pneumonia among Iranian pilgrims at Hajj was 24 per 10000 in 2004 and 34 per 10000 in 2005 [37]. Saudi Ministry of Health recommends vaccine of Influenza and Pneumococcal before the Hajj at age >65 years [38]. On the other hand, uptake of the vaccine depends on the knowledge and attitude of the pilgrims. Study of Sridhar S et al., to measure the Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) of French Hajj pilgrims showed that knowledge of pilgrims about the severity of pneumonia and the existence of the vaccine was very low and only 7% of 101 participants having an indication for pneumococcal vaccination were advised [39]. In another study, the rate of vaccination among Australian pilgrims in 2011, 2012, and 2013 years was 28.5%, 28.7%, and 14.2%, respectively. According to this study, the pneumococcal vaccine uptake among Australian pilgrims was decreasing in these years [40]. Using preventive measures such as vaccination by pilgrims helps to control preventable contagious diseases and prevent the global spread of these diseases.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, as the most common infectious cause of death worldwide, is one of the respiratory infections that may be disseminated in religious mass gatherings. The annual accumulation of numerous people, exhaustion, and poverty can cause the transmission of tuberculosis in religious mass gatherings and also the outbreak of this disease in the world [41-43]. Therefore, guidelines are required for surveillance, screening, prevention, transmission, treatment, and control of tuberculosis at mass gathering events [42]. Establishment of the health care system for Tuberculosis (TB) disease control is essential at religious mass gatherings. The return of pilgrims to their countries at the end of the ceremony and the global spread of the diseases is a challenge for origin countries. According to the results of the studies, because of the intense congestion and crowding, air and environmental pollution, reduced personal hygiene, and restriction of the health facilities, the transmission of communicable diseases especially airborne agents (such as influenza, pneumonia and Mycobacterium tuberculosis) is the most common health hazards at religious mass gatherings. The pilgrims which participate in religious mass gatherings are from different countries with various demographic characteristics. Some studies believed that different bacterial and viral agents contributed to the spread of respiratory diseases in pilgrims [28,31]. Overall, international strategies and cooperations minimise the risk of influenza in mass gatherings by preventive measures such as vaccination. Vaccination against seasonal and pandemic influenza and pneumococcal is necessary for people at risks such as children, the elderly, pregnant women and chronic patients before participation in religious mass gatherings. Also, improving the living conditions of pilgrims and reducing the density of pilgrims in shelters helps to reduce respiratory diseases. In addition, other preventive health measures such as screening vulnerable people, increasing the awareness of pilgrims about hand washing and the wearing of face masks, and antiviral agent’s prophylaxis is essential to prevent the spread of respiratory infections.

After respiratory tract infections, the gastrointestinal infections are the most common diseases in religious mass gatherings. The spread of communicable diseases such as gastrointestinal diseases is an important challenge pertinent to mass gatherings. Food poisoning and lack of hygiene at pilgrims are the causes of the disease [38,44,45]. Emamian MH and Mohammadi GM, in a study with the aim of assessment of the outbreak of gastroenteritis in Iranian female pilgrims at Hajj 2011 showed that among the 81 of women pilgrims, 16 patients suffered from gastroenteritis [46]. Poor hygiene and contaminated food and water in religious mass gatherings cause the outbreak of gastroenteritis in Pilgrims.

Few studies have revealed the prevalence of gastrointestinal infections, including diarrhoea, in religious mass gatherings. In the past, gastrointestinal diseases such as diarrhoea were one of the most common health threats in mass gatherings. Many factors may assist in this disease including inadequate standards of food hygiene, the deficit of water, and the lack of personal hygiene. Religious ceremonies such as Hajj and Arbaeen are stabilised according to the muslim lunar calendar, which changes with seasons, so that diarrheal disease increases in the warm season. Sanitation and good hygiene behaviour especially hand hygiene is recommended for the prevention of diarrheal diseases. The results of studies indicate that improvement of public health surveillance, hand hygiene and regular use of alcohol-based hand rubs can prevent the spread of gastrointestinal infections [6,29]. Also, in religious mass gatherings such as Kumbh Mela, bathing in rivers could cause gastrointestinal disease [7]. The training of pilgrims for hand hygiene and also the control of food production and distribution centres help to reduce gastrointestinal infections.

Meningococcal is one of the infectious diseases that cause the spread in human mass gatherings. According to the severity and consequences of Meningococcal disease and also the possibility of international spread, there is a need for immediate public health response [47].

Asymptomatic carriage of the meningococcal disease increases from 35% to 86% in the general population at mass gatherings such as Hajj. Despite the appropriate treatment, the mortality rate is 10%-30% due to the disease. So, based on World Health Organization guidelines, quadrivalent vaccination is a mandatory requirement for Hajj pilgrims [48]. Saudi Ministry of Health recommends vaccine of Polysaccharide quadrivalent meningococcal (>2 years of age) and Polysaccharide monovalent A meningococcal (<2 years of age) before the Hajj [38].

Contagious diseases related to religious mass gatherings vary based on the type, location, and diversity of the population. The combination of various factors such as high crowding, limited accessibility, inadequate crowd control and lack of on-site health care predictions may have the potential for the development of contagious diseases, and leading to catastrophic global consequences if they are not controlled. Religious mass gatherings are the origins of many people and attract pilgrims from all over the world. Demography, nation, gender, age, ethnic, and belief variation are common among such mass gatherings. Recognition of religious mass gatherings and explore the challenges and common diseases in the community help public health authorities and policymakers to create better and more effective preparedness and response plan.

Limitation

To the best knowledge, this systematic review is the first one to focus exclusively on communicable diseases at religious mass gatherings. Studies without abstract and studies published but not available in the data base screened were not included. On the other hand, this method may have excluded certain descriptive studies that may be relevant to planning and preparation at mass gatherings. The search terms used in this review were specific. Using additional search terms may have revealed additional publications. Overall, publications from the non-index literature and broader search terms may have produced additional literature and therefore provided further insight into religious mass gatherings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there are some data, indicating religious mass gatherings, are associated with the risk of communicable diseases. Most studies suggest that prevention and control programs together with other preventive measures such as screening vulnerable people, vaccination, personal hygiene, health education, preventive measures (such as hand hygiene and face masks), surveillance system, and improving the living conditions of pilgrims may reduce the risk of transmission of diseases and also may prevent the spread of communicable diseases in pilgrims returning to their country. International co-operations and strategies seem to be needed due to the high attraction of religious mass gatherings among pilgrims and also attention to the international spread of communicable diseases. The authors suggest that this type of study should be used for other mass gatherings, including sports, concerts, festivals, and shows.

Funding: This study is part of the PhD thesis. The study supported both financially and officially by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.