Introduction

BRICS is an acronym for association of world’s five emerging economies: Brazil, Russian Federation, India, China, and South Africa. Their combined GDP is more than one fifth the worldwide GDP [1]. With over 40% of the world’s population native to one of the BRICS nation, and with ever increasing globalization, it is safe to say that global health depends vastly on the health of the people from BRICS nations [2]. Consequently, the policies and regulations of these nations related to health, among other issues, have the potency to make a global impact. This article looks into the current health and healthcare scenario and what India can learn from the rest.

Situational Analysis

Healthcare system in BRICS [

3-

11]

Brazil

The establishment of National Health System in 1990 was a ground breaking development for a poor healthcare system that existed at that time and this has turned out to be the most significant mode of public expenditure on health ever since. The system is similar to the one present in the U.K., but with far more influence of the private sector [12]. But, with well-established public health sector in the country, it has been able to contain the growth of private sector to a large extent [13].

In Brazil, of the total health expenditure, public health expenditure amounts close to half (46%) [3]; of which, the central government make up 45%, leaving the rest to state and local authorities [13]. Brazil adopted right to healthcare in 1988 and consequently made reformation in policies such as introduction of Unified Health System (SistemaUnico de Saude-SUS), and Family Health Strategy (FHS) [8,14]. Around 25% of the Brazil’s population has some or the other kind of private insurance to supplement the above mentioned government schemes and coverage, and while government services are available to all, it is used mostly by the 20% of the population who are considered to be in the lower income bracket [13].

As per the assessment of World Bank, one of many great achievement of Brazil in health is bringing together different systems of health financing and service provision into one large public funded system covering the entire population, with efforts from all the tiers of government [15]. Brazil’s health system has had its controversial moments, to cover the rapid expansion of FHS and subsequent shortage of human resources, the government chose to import doctors from other countries leading to quality concerns [16]. Also, due to overcrowding and long delay in delivery of care, the financially capable segment of the population often end up seeking care in private sector, and they only return to public sector when the treatment is unaffordable [17].

With all its shortcomings and deficiencies, Brazil’s health sector has been on the upward turn since late 1990, and one that is exemplary to India in many aspects such as factors leading to Universal Health Coverage (UHC).

Russian Federation

In Russia Federation, the constitution of the country provides its entire citizen with right to free healthcare since early 1990s [7]. In principle, Russia has a universal coverage leading to at least a “guaranteed minimum”, while also providing healthcare through existence of expensive private sector, which is used by the most privileged and rich [18].

The public health expenditure in Russia is more than half (52%) of the country’s overall expenditure on health [3]. The free health care came in 1996 through Mandatory Medical Insurance which was followed by National Priority Project in Public Health in early 2000s and a series of reforms [19]. But this did not result in desired outcomes leading to “massive destabilization” because of the two channel mode of financing through wage taxes and general taxes [20]. The inadequate amount of inputs, including that of human resources resulted in “shadow commercialization” which essentially meant that government appointed medical personnel used informal shadow payments for their services [21].

The progressive changes can be seen with the introduction of law on Federal Mandatory Insurance Fund (FOMS) in 2010 and related measures taken to improve the healthcare systems in 2012 that featured increased financing for more personnel and equipment and, decentralization of the services to three tier system-federal, regional, and municipal [19].

China

Amongst BRICS Nations, China’s feat towards establishment of UHC has been remarked as exemplary since it started its reforms in 2009 [22,23]. China in its recent implementation plan tries to bring about affordable medical care to its citizens by 2020 [24].

The public health expenditure in China stands highest among BRICS nations at 55%, with private contributing the rest [3]. Presently, China’s healthcare system functions in a three-tier system; namely, at national, provincial, and county levels. The public insurance schemes comprise of three main systems that run hand in hand; namely, the New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS), the Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance (URBMI), and the Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI).

Along with this, the essential drug program also contributes to the reducing Out-of-Pocket (OOP) expenditure in China. Another important step taken towards achievement of UHC includes increasing the public health spending by twice. This has largely helped them to increase the strength of their public service as well as reducing OOP [9].

South Africa

Despite its small gross population and comparable GDP per capita against China and Brazil, it hasn’t been able to achieve similar levels of public health status and investments [1,2]. The African country has brought about a slew of developmental activities in health sector post its apartheid era to tackle in differences in availability and access to healthcare, such as public health legislations, unified national health systems, free of cost maternal and child health services etc. [25].

Public health spending is marginally less than private health spending at 47%. To improve the scenario, the government brought many reforms such as in 2008, with the Ten Point Plan. This was “to guide government health policy and identify opportunities for co-ordinated public and private health sector efforts, in order to improve access to affordable, quality health care in South Africa” [25].

In the year 2011, a Green paper to discuss the possibility of National Health Insurance (NHI) was brought, which had its objectives in increasing the quality of care provided and provide financial protection against catastrophic health expenditure by its people. The proposal also focused on partnership between public and private sector to realise comprehensive healthcare in the country, while also focusing on promotive and preventive services at community level [26].

Although it was due to be implemented in 2015, it did not, and the government proposed that NHI will be made an obligation of state and will come into place in a phased manner over a 14 year period. In Phase I of the process, the government will try to strengthen the public sector. The Phase II will include population registration and development of a transitional fund to purchase non specialist primary care. The Phase III will be the final phase which ends in utilising complete NHI funds and making it the single payer for complete and comprehensive care of the citizen [10].

While the NHI project is still in its infancy stage in the country, it is still a step towards right direction.

India

Unlike Brazil or Russia, The Indian constitution doesn’t advocate right to health as a fundamental right [27]. But, it considers “right to life” to be fundamental and obliges the state to ensure “right to health” for its people.

When compared to any other BRICS Nation, India’s public expenditure on health remains lowest at a little over 1% [3]. Let alone BRICS nations, 1% is lower than even the average for low income countries [28]. The consequence of such low spending is that India’s Private sector occupies the dominant position in out-patient as well as in-patient healthcare delivery including medical technology, diagnostic procedures, pharmaceuticals and hospital construction [29].

The highlight of Indian healthcare system is the catastrophic OOP expenditure for health that stands at 69% [3]. Another notable feature is, since health is state subject; each state has widely varying indicators with few states performing very well compared to others [28].

Efforts to widen health coverage have been few and far between. The notable programs that set towards wider healthcare coverage include National Health Mission (NHM) and Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY).

National Health Mission: The NHM, formerly called as National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) changed the functions of health system in many ways. The main aim of NRHM has been to “carry out necessary architectural correction in the basic health care delivery system” [30]. But at later stages, statistics have shown that NRHM may not have improved the health situation in the country as it had hoped initially, although it has led to betterment of few parameters related to antenatal care, immunization etc., [31].

Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana: This scheme was developed with social welfare and health of the poor laborers of the informal sector and presently claims to reach 41 million poor families. Of the studies that are present, on the positive effect the RSBY has had on health coverage such as reduction in OOP, the results seem to be mixed [32-34]. The studies also indicate that even the establishment of RSBY is a result of strong political will and further pushes towards the dream of UHC [35].

Beyond these, the glaring inadequacies of India in its public health infrastructure and availability are far more evident and the coverage of its health insurance schemes is far less compared to Russia, Brazil or China. A report from the World Bank states that health insurance through the schemes available in India such as the RSBY, the Central Government Health Scheme (CGHS), Employees’ State Insurance Scheme (ESIS), and other relatively minor government schemes provide coverage only for 25% of the population. Furthermore, it states that reach and variety of the benefits available through this scheme vary widely and a large majority of the population receive only very limited financial coverage [11]. This is an insight to be carefully examined by policy makers at center and state.

Even RSBY, the “largest scheme”, covers only 17% of the 1.3 billion people of the country and focuses only the population below poverty line while failing to protect people. Furthermore, it is of interest to note that the scheme only gives financial protection to inpatient services while not being able to cover majority of the population that lives in or is vulnerable to poverty [36,37]. With such poor coverage and lack of effort from the government albeit the private sector innovations in the manufacturing of pharmaceuticals and state-of-the-art delivery of health services for the medical tourism industry, the UHC seems like a far-fetched dream.

This is further evidenced by the critics who emphasise that the insurance-model from the healthcare delivery of private sector is barely going to lead to UHC [38]. While some have even gone on to term India’s model as the “Trojan horse” of neoliberalism as the healthcare at primary level is heavily affected [39].

[Table/Fig-1,2 and 3] compare the Population, GDP per capita and health expenditure to compare amongst BRICS nations.

Health expenditure [1-3].

| Country | Population (2017) (in Crores) [2] | GDP per capita (US $) (2016) [1] | GDP (PPP) per capita (US $) (2016) [1] | Human Development Index (2017) | Public Health Expenditure % of GDP (2014) [3] | Private Health Expenditure % of GDP (2014) [3] |

|---|

| Brazil | 21 | 8649 | 15123 | 0.754 | 3.8 | 4.5 |

| Russia | 14 | 8748 | 24788 | 0.804 | 3.7 | 3.4 |

| India | 132 | 1710 | 6570 | 0.624 | 1.4 | 3.3 |

| China | 138 | 8123 | 15521 | 0.738 | 3.1 | 2.5 |

| South Africa | 5.59 | 5274 | 13196 | 0.666 | 4.2 | 4.6 |

Source: World Bank

Healthcare facilities and Insurance [4-11].

| Countries | Hospital Beds (per 1,000 people) (2011) [4] | Physicians (per 1000 people) (2011) [5] | Nurses and Midwives (per 1,000 population) (2011) [6] | Public Health Insurance (2011) [7-11] |

|---|

| Brazil | 2.3 | 1.8 | N/A | SistemaUnico de Saude-SUS |

| Russia | N/A | 2.4 | N/A | Federal Compulsory Medical Insurance Fund |

| India | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.7 | ESIS, CGHS, RSBY, Public-Private Partnerships |

| China | 3.8 | 1.5 | 1.7 | NCMS, URBMI, and UEBMI |

| South Africa | N/A | 0.7 | 4.6 | National health Insurance, in development. |

Source: World Bank, WHO

BRICS’ total health expenditures (WHO NHA data) [12].

| Total Health Expenditure per capita (current $ PPP) | Public expenditure health per capita (current $ PPP) | Private expenditure health per capita (current $ PPP) | OOP expenditure per capita (current $ PPP) |

|---|

| Per capita health spending | 1995 | 2013 | 1995 | 2013 | 1995 | 2013 | 1995 | 2015 |

| Brazil | 522 | 1454 | 225 | 701 | 298 | 753 | 202 | 394 |

| Russian Federation | 301 | 1587 | 222 | 762 | 79 | 825 | 51 | 515 |

| India | 63 | 215 | 17 | 69 | 46 | 146 | 42 | 155 |

| China | 61 | 646 | 31 | 360 | 30 | 278 | 28 | 247 |

| South Africa | 478 | 1121 | 189 | 543 | 288 | 578 | 67 | 84 |

Population Health

In comparison of Infant Mortality Rate (IMR), and Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR), Russia comes out as the best performer, while China comes in as a close second. This is followed by Brazil. South Africa takes third and India comes in as the worst performer of the lot; with the last two nations being way behind the rest. When it comes to Life expectancy at birth, China and Brazil comes out as best and second best performers respectively; followed by Russia and then India and South Africa respectively [Table/Fig-4] [40-42].

Population health [40-42].

| Country | Life Expectancy (years) at birth (2015) [40] | IMR (per 1000 birth) (2016) [41] | MMR (per 100,000 birth) (2015) [42] |

|---|

| Brazil | 75 | 14 | 44 |

| Russia | 72.9 | 7 | 25 |

| India | 68.3 | 35 | 174 |

| China | 76.1 | 9 | 27 |

| South Africa | 62.9 | 34 | 138 |

Source: World Bank, World Health Organization

What can India learn?

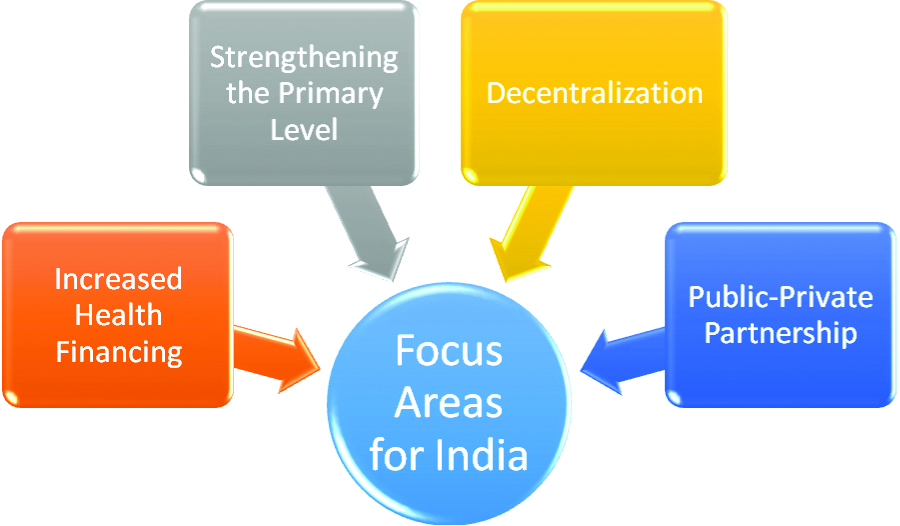

India has a lot of takeaways and valuable insights from how the other countries tried to improve their health, especially in the case of Russia and Brazil. The first and key difference is that all these countries barring India have a national document enlisting and describing their vision towards UHC, although Russia and South Africa have translated these into operational objectives completely and are dealing with operational inefficiencies. Based on the observations made, these articles broadly classify areas of improvement into four [Table/Fig-5].

Increased Health Financing: While both Brazil and China have made tremendous progress towards health coverage and reforms, the path these two countries took are different. Brazil’s progress, as described before, was gradual and incremental while China took a path of fast-paced approach. This may be largely attributed to the overachievement of the Chinese economy as a whole. If India is to achieve more health coverage for its people, it may have to choose the path taken by China and immediately prioritize the spending on health. But the latter approach also has its benefits such as gradual and incremental change won’t bring about distress due to sudden and abrupt change. There are few key factors that need to be looked into while moving forward in approach taken.

Strengthening the Primary level: Strengthening the primary level of care with adequate personnel and equipment is one of the foremost step towards achieving better population health. Brazil and China have been able to do so as described above. Even Russia is another example, although there is start difference between privileged and others. They have been able to provide a fair minimum care to their population. India should either concentrate on a UHC program or invest in its primary care.

Decentralization: Another important factor that emerges from the analysis above is the degree of decentralization. Each of the BRICS nations has its very own federal structure. As such, much of the health care delivery happens through this these levels of federal structures. In China, the financial decentralization has meant many health care delivery facilities relying on the financial strengths of their local bodies [9]. In South Africa, the decentralization coupled with poor and rich areas has led to inequalities in care [25]. Russia has varied human resource availability across regions as discussed above, that has led to financial allocation being uneven [21]. Brazil on the other hand has minimal issues compared to above mentioned countries and is the one India should follow while articulating its own visions and objectives towards financing of health in the context of a federal structure.

Public Private Partnership: This is an area requiring much attention. Each of the countries has their own share of private sector contribution towards health [Table/Fig-5], but nothing compared to the state of affairs in India. In Brazil, the private sector contributes within the ambit of National Health Services. In China, the government has encouraged private partnerships, with private hospitals even being eligible to provide reimbursable treatment for patients funded through social health insurance of the country [43]. India will have to analyse the effects of partnership with private sector on its people and compare it with other countries and move forward in a way that improves the healthcare scenario of the country.

Conclusion

BRICS countries excluding South Africa leaves India with a lot of catching up to do in healthcare. But on the positive note, it also helps India to learn from the mistakes of these countries towards their progress and learn from it.

[1]. World Bank, GDP, Current. [Online] 2017 [cited 2018 March 23 Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD [Google Scholar]

[2]. World Bank, Population total. [Online] 2017 [cited 2018 March 23 Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL [Google Scholar]

[3]. world Bank, Health Expendiure. [Online] 2014 [cited 2018 March 24 Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.PRIV.ZS [Google Scholar]

[4]. World Bank, Hospital Beds (Per 1000 population). [Online] 2011 [cited 2018 March 28 Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.BEDS.ZS?end=2011&locations=CN-IN-RU-BR-ZA&start=1960&view=chart [Google Scholar]

[5]. World Bank, Physicians (per 1000 population). [Online] 2011 [cited 2018 March 28 Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.PHYS.ZS?end=2011&locations=CN-IN-RU-BR-ZA&start=1960&view=chart [Google Scholar]

[6]. World Bank, Nurses and midwives (per 1,000 people). [Online] 2011 [cited 2018 March 28 Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.NUMW.P3?end=2011&locations=CN-IN-RU-BR-ZA&start=1960&view=chart [Google Scholar]

[7]. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, WHO. World Health Organization, Regional office for Europe. [Online].; 2011 [cited 2017 March 24. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/157092/HiT-Russia_EN_web-with-links.pdf [Google Scholar]

[8]. Elias PE, Cohn A, Health reform in Brazil: Lessons to considerAmerican Journal of Public Health 2003 1(93):44-48.10.2105/AJPH.93.1.4412511382 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9]. World Bank. World Health Organization, Ministry of Finance, National Health and Family Planning Commission, Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security. Deepening Health Reform In China: Building High-Quality And Value-Based Service Delivery. [Online].; 2016 [cited 2018 March 24. Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/24720/HealthReformInChina.pdf [Google Scholar]

[10]. Gray A, Vawda Y, Health policy and legislationIn South African Health Review 2016 Health Systems Trust2016 [Google Scholar]

[11]. World Bank, Government-Sponsored Health Insurance in IndiaAre You Covered? [Online] 2012 [cited 2018 March 24 Available from: http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2012/10/11/government-sponsored-health-insurance-in-india-are-you-covered [Google Scholar]

[12]. Jakovljevic M, Potapchik E, popovich L, Barik D, Getzen TE, Evolving health expenditure landscape of the BRICS Nations and Projections to 2025Health Economics 2017 July 26(7):844-52.10.1002/hec.340627683202 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[13]. Cohn A, The Brazilian health reform: A victory over the Neo-liberal ModelSocial Medicine 2008 3(2):71-81. [Google Scholar]

[14]. WHO. [Bulletin].; 2008 [cited 2018 March 24. Available from: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/4/08-030408/en/ [Google Scholar]

[15]. World Bank, Twenty years of health system reform in Brazil : an assessment of the sistema unico de saude [Online] 2013 [cited 2018 March 24 Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/909701468020377135/Twenty-years-of-health-system-reform-in-Brazil-an-assessment-of-the-sistema-unico-de-saude [Google Scholar]

[16]. PAHO. Brazil’s "More Doctors" initiative has taken health care to 63 million people. [Online].; 2015 [cited 2018 March 24. Available from: http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=11257%3Abrazils-more-doctors-initiative-has-taken-health-care-to-63-million-people-&catid=740%3Apress-releases&Itemid=1926&lang=en [Google Scholar]

[17]. Khazan. What the U.S. Can Learn From Brazil’s Healthcare Mess, The Atlantic. [Online].; 2014 [cited 2018 March 24. Available from: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/05/the-struggle-for-universal-healthcare/361854/ [Google Scholar]

[18]. Cook LJ, Constraints on universal health care in the Russian Federation: Inequality, Informality and the failures of mandatory health insurance reformsSpringerLink 2017 March Available from: http://www.unrisd.org/80256B3C005BCCF9/3C45C5A972BF063BC1257DF1004C5420/ $file/Cook.pdf [Google Scholar]

[19]. Danishevski K, Balabanova D, Mckee The fragmentary federation: experiences with the decentralized health system in RussiaThe Journal on Health Policy and System Research 2006 21(3):183-94.10.1093/heapol/czl00216501049 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[20]. Twigg JL, Balancing the state and the market: Russia’s adoption of obligatory medical insuranceEurope-Asia Studies 1998 50(4)10.1080/09668139808412555 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[21]. Blam I, Kovalev On Shadow Commercialization of Health Care in Russia. In Commercialization of Health CarePart of the series Social Policy in a Development:117-135.10.1057/9780230523616_8 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[22]. Yip WC, Hsiao WC, Chen W, Hu S, Ma J, Maynard A, Early appraisal of China’s huge and complex health-care reformsThe Lancet 2012 379(9818):833-42.doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61880-110.1016/S0140-6736(11)61880-1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[23]. Yu H, Universal health insurance coverage for 1.3 billion people: What accounts for China’s success?Health Policy 2015 119(9):1145-52.10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.07.00826251322 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[24]. WHO. WHO Representative Office-China. Factsheet on Health sector reform in China. [Online]. [cited 2018 March 24. Available from: http://www.wpro.who.int/china/mediacentre/factsheets/health_sector_reform/en/ [Google Scholar]

[25]. Schaay N, Sanders Kruger V, Overview of Health Sector Reforms in South AfricaDFID report. [Online] 2011 [cited 2018 March 24 Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08abc40f0b64974000740/overview_of_health_sector_reforms_in_south_africa.pdf [Google Scholar]

[26]. Matsoso MP, Fryatt R, National Health Insurance: The first 18 monthsThe South African Medical Journal 2013 103(3)Available from: https://journals.co.za/content/m_samj/103/3/EJC13166810.7196/SAMJ.660123472691 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[27]. The Economic TimesRight to health be made a fundamental right: bill in RS. [Online] 2017 [cited 2018 March 24 Available from: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/right-to-health-be-made-a-fundamental-right-bill-in-rs/articleshow/62106162.cms [Google Scholar]

[28]. National Health Profile. [Online].; 2016 [cited 2018 March 24. Available from: http://cbhidghs.nic.in/E-Book%20HTML-2016/files/assets/basic-html/page-47.html [Google Scholar]

[29]. Duran A, Kutzin J, Menabde N, Universal coverage challenges require health system approaches; the case of IndiaHealth Policy 2013 December Available from: “https://www.clinicalkey.com/#!/content/playContent/1-s2.0-S0168851013003060” [Google Scholar]

[30]. Government of India. National Rural Health Mission. [Online].; 2005 [cited 2018 March 24. Available from: http://www.nipccd-earchive.wcd.nic.in/sites/default/files/PDF/NRHM%20-%20Framework%20for%20Implementation%20-%20%202005-MOHFW.pdf [Google Scholar]

[31]. Hussain Z, Health of the National Rural Health MissionEconomic & Political Weekly 2011 46(4):53-60. [Google Scholar]

[32]. Selvaraj S, Karan AK, Why Publicly-Financed Health Insurance SchemesAre Ineffective in Providing Financial Risk ProtectionEconomic and Political Weekly 2012 :60-68. [Google Scholar]

[33]. Fan VY, Karan A, Mahal A, State health insurance and out-of-pocket health expenditures in Andhra Pradesh, IndiaInternational Journal of Health Care Finance and Economics 2012 July Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10754-012-9110-510.2139/ssrn.2102772 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[34]. Shahrawat Rao D, Insured yet vulnerable: out-of-pocket payments and India’s poorHealth Policy and Planning 2012 27(3):213-221.10.1093/heapol/czr02921486910 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[35]. Shroff ZC, Roberts MJ, Reich MR, Agenda Setting and Policy Adoption of India’s National Health Insurance Scheme: Rashtriya Swasthya Bima YojanaHealth Systems and Reform 2015 1(2)Available from : https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23288604.2015.103431010.1080/23288604.2015.1034310 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[36]. Mehrotra S, Kumra N, Gandhi A, India’s Fragmented Social Protection System: Three Rights Are in Place; Two Are Still MissingUnited Nations Research Institute for Social Development 2014 December Available From: http://www.unrisd.org/80256B3C005BCCF9/(httpAuxPages)/329A49D52B87C006C1257DA30048CB70/$file/Mehrotra%20et%20al.pdf [Google Scholar]

[37]. Dasgupta R, Nandi S, Kanungo K, Nundy M, Murugan G, Neog R, What the Good Doctor Said: A Critical Examination of Design Issues of the RSBY Through Provider Perspectives in Chhattisgarh, IndiaSocial Change 2013 43(2)Available From: https://doi.org/10.1177/004908571349304310.1177/0049085713493043 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[38]. Mukhopadhyay I, Universal Health Coverage: The New Face of NeoliberalismSocial Change 2013 43(2)Available From: https//10.1177/00490857134922810.1177/0049085713492281 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[39]. Qadeer I, Universal Health Care: The Trojan Horse of Neoliberal PoliciesSocial Change 2013 July 43(2)Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177%2F004908571349303710.1177/0049085713493037 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[40]. WHO. WHO | Life expectancy. [Online].; 2015 [cited 2018 March 24. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.688 [Google Scholar]

[41]. World Bank, Mortality rate, Infant. [Online] 2016 [cited 2018 March 24 Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.IMRT.IN [Google Scholar]

[42]. World bank, Maternal mortality ratio (modeled estimate, per 100,000 live births). [Online] 2015 [cited 2018 March 24 Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.MMRT [Google Scholar]

[43]. The economist, White paper-China’s emerging private healthcare sector. [Online] 2016 [cited 2018 March 24 Available from: http://www.eiu.com/industry/article/1954017979/white-paper-chinas-emerging-private-healthcare-sector/2016-03-10 [Google Scholar]