Use of a Locking Compression Plate in the Management of Congenital Pseudarthrosis of the Tibia

Norliyana Mazli1, Mohd Yazid Bajuri2, Abdul Muhaimin Ali3, Srijit Das4

1 Senior Registra, Department of Orthopaedic and Traumatology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre, Cheras, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

2 Associate Professor, Department of Orthopaedic and Traumatology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre, Cheras, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

3 Medical Research Officer, Department of Orthopaedic and Traumatology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre, Cheras, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

4 Professor, Department of Anatomy, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre, Cheras, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr Mohd Yazid Bajuri, Associate Professor, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre, Cheras, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

E-mail: ezeds007@yahoo.com.my

Congenital pseudarthrosis of tibia is a rare condition and it is highly associated with neurofibromatosis. The goals of surgery are to restore the tibial alignment, achieve bone union and re-establish the length of the tibia. The treatment includes resection of the pseudarthrosis followed by fixation with external fixation devices to perform callus distraction, intramedullary nail or open reduction and plate fixation in combination with bone graft. We present a case of a 16-year-old male with underlying neurofibromatosis and congenital pseudarthrosis of right distal third of tibia. Patient was treated with excision of the pseudarthrosis followed by reduction and fixation using locking compression plate and bone graft. Radiograph showed union of the tibia at eight months postoperation. Patient had limb length discrepancy of 10 cm and was ambulating with a shoe raised. At two years follow-up, there was no refracture of the tibia. The patient was satisfied with his current functional status and had adapted well. Due to his good functional outcome, he declined to undergo limb lengthening surgery. We thereby concluded that locking compression plate may be considered as a suitable option for the treatment of congenital pseudarthrosis of tibia.

Congenital deformity, Neurofibromatosis, Plate fixation

Case Report

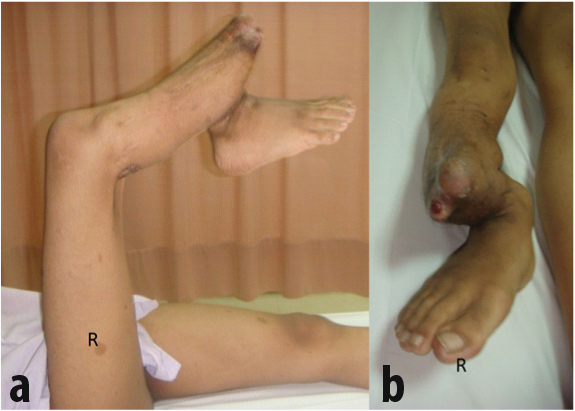

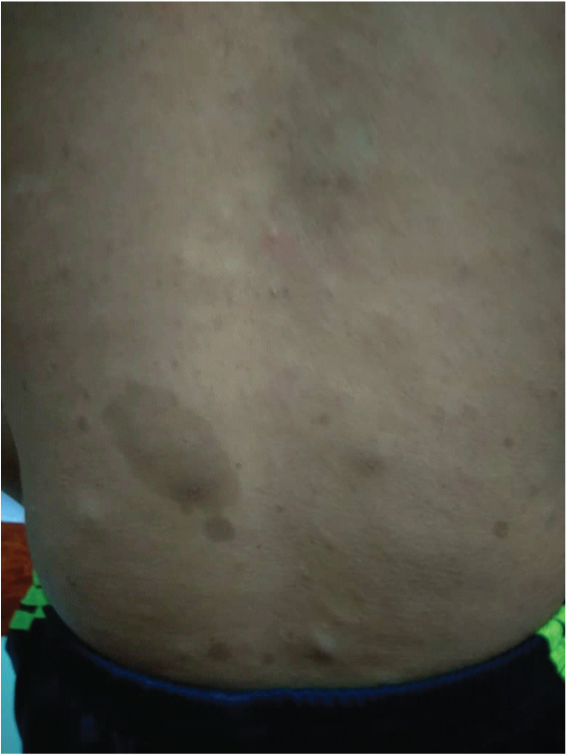

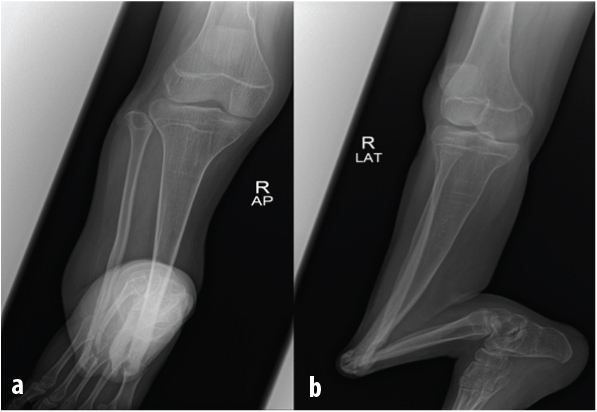

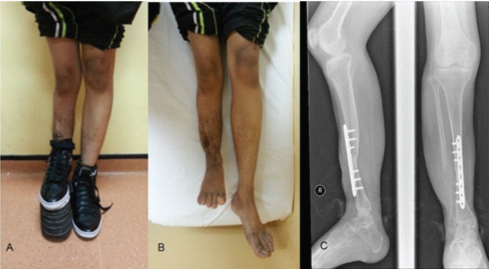

A 16-year-old male presented with complaint of pain of right leg following a fall three years ago. The patient’s medical history included neurofibromatosis with anterolateral bowing of the right tibia. No family history of the same condition and no history of consanguineous marriage in family. He had been treated with Illizarov external fixator at one year of age for 18 months. After that, he had difficulty in ambulation because of right lower limb deformity and unequal limb length. Examination revealed deformity of the right tibia fibula at the distal third of the leg [Table/Fig-1a and b]. The right knee noted to be supple with equinovarus ankle deformity with limited range of motion of 20° and the left lower limb was normal. There were multiple café-au lait macules over the upper back [Table/Fig-2] and bilateral upper limbs. Radiograph of the lower limb [Table/Fig-3 a and b] showed deformed tibia fibula with mid shaft pseudarthrosis and osteopenia (Crawford type IIC). The proximal tibia axis was misaligned to 140° with osteoarthritic changes of ankle and subtalar joints. CT angiogram revealed patent right lower limb vessels down to the level of ankle joint.

(a) The patient had marked angulation and deformity of the right leg. (b) Prominent bone impinging on the skin.

Café au lait spots on patient’s back.

(a) The anteroposterior radiograph of right leg showing deformed tibia fibula with pseudarthrosis and osteopenia. (b) The lateral view radiograph showing angulation of the right tibia with osteoarthritic changes of talus and calcaneal bone.

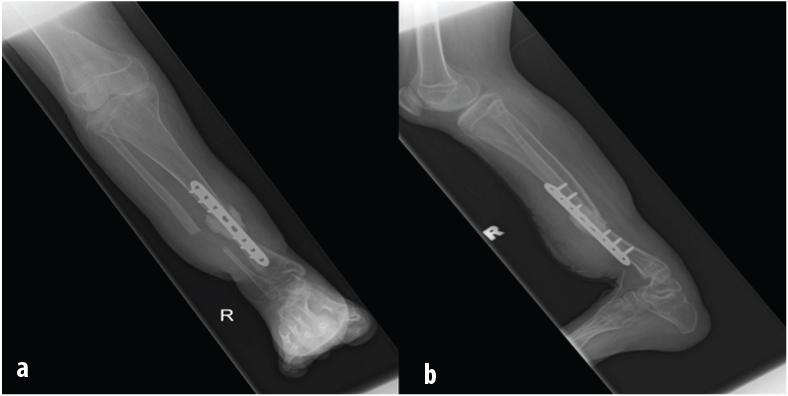

The patient underwent surgery where he was put under general anaesthesia. Tourniquet was inflated for a total of 2 hours and 30 minutes. Findings intra-operatively, the non-union site consisted of fibrotic tissue and the canal of tibia was noted to be obliterated and small. A diagnosis of pseudarthrosis tibia with osteoarthritis of ankle was made. The pseudoarthrosis was osteomised at the level measured 2 cm distal and 2 cm proximal from the non-union site of tibia and 3 cm proximal with 3 cm distal of fibula. There was punctate bleeding at bone edges after osteotomy. Bone was re-aligned, approximated and stabilized with eight holes 3.5 mm locking compression plate. An amount of 10 cc of resorbable bone graft (Genex®) was used. Postoperative radiograph showed good alignment with acceptable anterior bowing of 10° [Table/Fig-4a and b]. Patient was taught non-weight bearing ambulation with crutches and other appropriate physiotherapy regimes. He was discharged on postoperative day four. On follow-up at two months duration, he was able to partial bear weight without pain with good range of motion of knee and ankle. The wound healed with limb length discrepancy of 10 cm of the right lower limb. Radiograph on follow-up showed union of the tibia at eight months postoperation [Table/Fig-5 a and b]. Two years following operation, he was able to ambulate with shoe raise and was able to ride bicycle. The SF-36v2 Health Survey revealed that his physical health summary score was very much below average, 34 and his mental health summary score was above average, 57. The patient declined to undergo limb lengthening surgery as he was satisfied with his current functional status and had adapted well.

(a) The anteroposterior and (b) lateral view radiograph of right tibia fibula. Locking compression plate was used to stabilize the reduction. Good alignment of right tibia postoperative.

Photograph taken two year’s Postoperative. a) The patient standing with shoe raise on the right lower limb. b) Limb length discrepancy of 10 cm compared to left lower limb. c) The radiograph shows union of tibia.

Discussion

Congenital Pseudarthrosis of the Tibia (CPT) is a rare condition which is characterized by segmental dysplasia of tibial diaphysis resulting in anterolateral bowing of bone tibial non-union and reduced growth in the distal tibial epiphysis [1]. Among the children with CPT, approximately 50% of cases are diagnosed with neurofibromatosis [2]. The most widely used classification system by Crawford divides the congenital pseudoarthrosis of tibia into four categories as shown in [Table/Fig-6] [3]. The abnormal tissue at the pseudarthosis site is referred as fibrous hamartoma. This lesion arises from aberrant periosteal growth which is the key pathological findings in pseudarthrosis. Histological study of this lesion demonstrates fibromatosis-like tissue which is in continuous with the periosteum of the bone [4]. This fibrous hamartoma is responsible for poor healing potential because of restriction of blood flow that result to impair circulation to the pseudarthrosis site [5]. The fibrous hamartoma cells also have high osteoclastogenicity and low osteogenecity properties that contribute to recurrence of pseudarthrosis [4].

Crawfold Classification of Congenital Pseudoarthrosis of Tibia.

| Nondysplastic |

|---|

| Type I | Anterolateral bowing with increased bone densitySclerosis of the medullary canalPossibility of conversion to dysplastic type after osteotomy to correct angulation |

| Dysplasctic |

| Type II | Subtype A | Anterolateral bowing with failure of tubularization |

| Subtype B | Anterolateral bowing with cyst |

| Subtype C | Frank pseudarthrosis and atrophy with “sucked candy” narrowing of the ends of the two fragments |

The management of CPT still remains a challenging problem in paediatric orthopaedics. The main goal of surgery is to achieve bone union, restoring the leg alignment and to preserve function and bone growth [5]. Achieving union of pseudarthrosis in these children with CPT may require multiple surgical procedures. The functional outcome of the treatment is fair due to residual deformities, joint stiffness and remaining limb length inequalities [5]. The patient needed staged surgery to address the limb length discrepancy in order to achieve the acceptable limb length when compared to the non-involved side. Various methods of treatment include excision of the lesion, followed by stable internal or external fixation with vascularized or non-vascularized graft. The three surgical techniques: intramedullary nailing with a bone graft; vascularized fibular transfer; and the Ilizarov technique were reported with varying results and complications [5-9].

We describe a case of CPT treated with excision of the pseudarthrosis followed by reduction and fixation using locking compression plate and bone graft. The patient achieved bony consolidation, good leg alignment and able to ambulate with shoe raise to compensate for limb length discrepancy.

Treating congenital pseudarthrosis pose challenges when it come to achieving bone union, preventing recurrent fracture, restoring leg alignment and preserving bone growth and function [5,9]. Combination of three components are needed to effectively treat this recalcitrant fracture effectively which are excision of the pseudarthrosis and surrounding hamartomatous tissue, autogenous bone grafting and adequate fixation [6].

Three operative techniques: intramedullary nailing with bone grafting, the Ilizarof technique and vascularized free fibular transfer with follow-up to skeletal maturity were reported have equivalent results and no one surgical technique is superior [9]. Removal of pathological periosteum and fibromatous tissue during surgery increase the healing rate. The amount of soft tissue to be excised has to be planned because radical excision will result in problems of reconstruction of a large defect and may place the adjacent neurovascular structures at risk [9].

The most acceptable method of treatment of congenital pseudarthrosis of tibia is the Ilizarov method especially in dysplastic type that requires extensive resection of the pseudarthrosis [10,11]. Ilizarov method provides excellent regeneration of bone and uses the callus distraction technique which offers advantages in dealing with massive bone defect and shortening. This method also allows the correction of deformity in a single stage surgery. However, Ilizarov method requires a long period of treatment, relative complexity and possibility of wire-tract infections [12].

Vascularized fibular graft is another treatment of choice as it permits initial tibial consolidation [5-7]. This method is frequently combined with Ilizarov external fixator or intramedullary rod to achieve good tibial alignment, stability and prevents re-fracture. Previous study recommended this method as a primary treatment option and promising excellent long term results of vascularized fibular graft for CPT treatment [13]. Complications of this method includes re-fracture, malalignment (anterior bowing or valgus deformity) of the affected tibia, valgus ankle deformity on donor site, and failure to correct limb length discrepancy and deformities of leg and ankle at the time of primary surgery [6].

Numerous authors have reported the use of intramedullary rod for the treatment of congenital pseudarthrosis of tibia [1,6]. The primary treatment modalities for this disease is still circular fixation as well as intramedullary nailing [14,15]. This method is preferred in younger children as it reduces the frequency of re-fracture, provides stability and does not disturb distal tibial epiphysis [1]. It also provides alignment, correction of deformity and guides bone lengthening during growth [5]. The usage of intramedullary rod will increase the risk for ankle stiffness due to transfixation of the subtalar and tibiotalar joints, immobilization post insertion of intramedullary rod, and possibility of fracture after removal of the implant and will result the ankle into valgus deformity [1,6]. Resection of the pseudarthrosis which followed by stabilization using intramedullary rod, compression with circular frame, and simultaneous proximal tibia lengthening in combination with bone morphologic proteins and bone grafting were the other options suggested for CPT management [8]. There is a case where a teenager is treated using an adult-type nailing fortunately, the risk of greater trochanter epiphysiodesis is bearable at this age [16].

In the present case, the tibia canal was small and obliterated, thus he was not suitable for intramedullary device. We excluded the option of external ring fixator as patient was not in favour of the bulky fixator. The patient was treated with excision of the pathologic bone ends, and stabilized with locking compression plate in combination with absorbable bone graft (Genex®). This bone graft consisted of β-tricalcium phosphate/calcium sulfate hemihydrate compound. It is an absorbable synthetic bone graft with osteoconductive properties. The negatively charged surface chemistry attracts osteogenic proteins and osteogenic cell proliferation for bone formation. This method is not widely reported compared to the previously mentioned methods.

Conclusion

The fixation technique using locking compression plate in combination with bone graft improves the management of complex congenital pseudarthrosis of tibia. Limb lengthening procedure is feasible at a later stage once union of pseudarthrosis is achieved. This may obviate the need for treatment using complex external fixator in a highly specialized tertiary centre. However, this method needs more implementation and long term follow up to study the effectiveness and possible complications.

[1]. Shah H, Rousset M, Canavese F, Congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia: Management and complicationsIndian Journal of Orthopaedics 2012 46(6):61610.4103/0019-5413.10418423325962 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2]. Vitale MG, Guha A, Skaggs DL, Orthopaedic manifestations of neurofibromatosis in children: an updateClinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® 2002 401:107-18.10.1097/00003086-200208000-0001312151887 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[3]. Crawford AH, Schorry EK, Neurofibromatosis in children: the role of the orthopaedistJAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 1999 7(4):217-30.10.5435/00124635-199907000-00002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[4]. Cho TJ, Seo JB, Lee HR, Yoo WJ, Chung CY, Choi IH, Biologic characteristics of fibrous hamartoma from congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia associated with neurofibromatosis type 1JBJS 2008 90(12):2735-44.10.2106/JBJS.H.0001419047720 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[5]. Pannier S, Congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibiaOrthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research 2011 97(7):750-61.10.1016/j.otsr.2011.09.00121996526 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[6]. Dobbs MB, Rich MM, Gordon JE, Szymanski DA, Schoenecker PL, Use of an intramedullary rod for treatment of congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia: a long-term follow-up studyJBJS 2004 86(6):1186-97.10.2106/00004623-200406000-0001015173291 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[7]. Boero S, Catagni M, Donzelli O, Facchini R, Frediani PV, Congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia associated with neurofibromatosis-1: treatment with Ilizarov’s deviceJournal of Pediatric Orthopaedics 1997 17(5):675-84.10.1097/01241398-199709000-000199592010 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[8]. Shabtai L, Ezra E, Wientroub S, Segev E, Congenital tibialpseudarthrosis, changes in treatment protocolJournal of Pediatric Orthopaedics B 2015 24(5):444-49.10.1097/BPB.000000000000019125932825 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9]. Khan T, Joseph B, Controversies in the management of congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia and fibulaBone Joint J 2013 95(8):1027-34.10.1302/0301-620X.95B8.3143423908415 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[10]. Ohnishi I, Sato W, Matsuyama J, Yajima H, Haga N, Kamegaya M, Treatment of congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia: a multicenter study in JapanJournal of Pediatric Orthopaedics 2005 25(2):219-24.10.1097/01.bpo.0000151054.54732.0b15718906 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[11]. Borzunov DY, Chevardin AY, Mitrofanov AI, Management of congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia with the Ilizarov method in a paediatric population: influence of aetiological factorsInternational Orthopaedics 2016 40(2):331-39.10.1007/s00264-015-3029-726546064 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[12]. Simonis RB, Shirali HR, Mayou B, Free vascularised fibular grafts for congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibiaBone & Joint Journal 1991 73(2):211-15.10.1302/0301-620X.73B2.2005141 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[13]. Sakamoto A, Yoshida T, Uchida Y, Kojima T, Kubota H, Iwamoto Y, Long-term follow-up on the use of vascularized fibular graft for the treatment of congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibiaJournal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research 2008 3(1):1310.1302/0301-620X.73B2.200514118325091 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[14]. Horn J, Steen H, Terjesen T, Epidemiology and treatment outcome of congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibiaJ Child Orthop 2013 7(2):157-66.10.1007/s11832-012-0477-024432075 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[15]. Nicolaou N, Ghassemi A, Hill RA, Congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia: theresults of an evolving protocol of managementJ Child Orthop 2013 7(4):269-76.10.1007/s11832-013-0499-224432086 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[16]. B de Billy B, Gindraux F, Langlais J, Osteotomy and fracture fixation in children and teenagersOrthopaedics and Traumatology: Surgery and Research 2014 100(1 S):S139-48.10.1016/j.otsr.2013.11.00624394918 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]