Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is currently the established gold standard for symptomatic cholelithiasis. Frequency of this procedure is progressively increasing globally. Any unexpected turn of events intra-operatively has significant immediate and long-term implications for the patient, operating team, anaesthesia team, operation theatre management and the hospital in general. In case of LC these implications get multiplied many fold, mainly by virtue of the high number of cases. Another aspect is that high volume of cases, though good for the surgical skill learning curve, can induce a casual approach and limit preparedness for technical difficulty, thus catching the team off-guard. When a surgical team, unprepared for technical difficulties, struggles around unpaired vital structures like common bile duct, portal vein, common hepatic artery, significant morbidities and even mortality can result. Even if morbidity and mortality are avoided, a lot of un-booked time is lost, and skilled manpower can be squandered unnecessarily [1,2].

Thus, if the degree of technical difficulty could be predicted before starting the procedure, the concerned team can be better prepared and several of the adverse outcomes can be potentially minimised or forestalled. The need for such a system has been felt since the time LC was established as the gold standard for treatment of cholelithiasis. Several scoring systems have been coming up in scientific literature for almost the last couple of decades by various authors. But unfortunately none has been universally accepted or established to the level of being integrated into practice. This article aims to address this knowledge gap. The article is a part of larger study part of which has already been published [3].

Materials and Methods

It was a one-year prospective analytical study, from August 2012 to July 2013, conducted in Sikkim Manipal Institute of Medical Sciences, Gangtok. We calculated a sample size of 125 (for an α error of 0.05 and a β error of 0.20) using Medcalc© software.

Patients undergoing LC for symptomatic cholelithiasis as well as for already established indications for asymptomatic cholelithiasis viz., size of calculus <3 mm or >3 cm, associated with polyp, life expectancy of >20 years and associated diabetes mellitus were included in the study. Equipment or other technical failure, complicated cholelithiasis (associated with pancreatitis, choledocholithiasis), co-morbidities other than hypertension or diabetes mellitus were the exclusions. Experience of the surgeons was another major confounding factor which was best taken care of by excluding those cases which were performed by surgeons who had an experience of less than one year or had not performed at least 30 cases. Surgeries done in the institute are both conventional four port as well as reduced port surgeries. To maintain uniformity, care was taken not to include those patients in the final analysis who had undergone reduced port surgeries or any other deviation (like using 5 mm port in the epigastrium) from the operative protocol standardised for the study. Only those patients were included where the cystic duct was clipped (and not ligated) and retrieval bag was used to bring the gall bladder out.

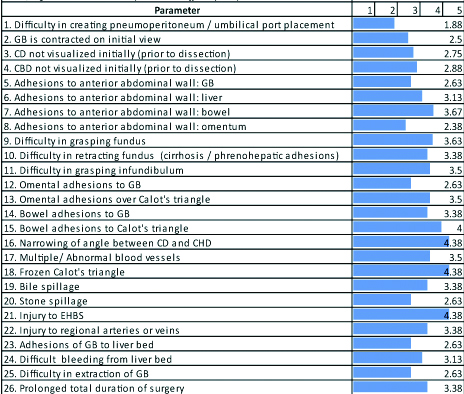

A list of pre-operative variables was prepared to be compared with the outcome variable that was the difficult LC. Difficulty assessment was done by a Likert type questionnaire which was e-mailed to practising laparoscopic surgeons across the country. On the basis of the personal experience and perception, surgeons were asked to grade the operative events on a scale of 1-5, depending on how important each factor was for the surgeon in making a LC difficult. On the basis of responses obtained from them, a WDS was calculated as WDS=∑ (PR x DRS) where PR was the parameter response recorded as one [1] for its presence or zero [0] for absence and DRS was the difficulty response score on a scale from 1 to 5. Mean WDS was then compared against pre-operative parameters. Data was tabulated and analysed using Microsoft© Excel© 2013 and IBM© SPSS© 20.0.

Results

For the last ten years, about 250-400 cholecystectomies are being done in the study hospital. A total of 125 successive consenting patients were recruited, who underwent LC in the study duration. There was no difference found when these 125 patients were matched for their age and sex to total number of patients who underwent LC during the study duration thus, reducing the inclusion bias [Table/Fig-1].

Age and sex standardization. [All cases are the total number of cholecystectomies in study duration. Study group is the sample size of 125 patients.

| Parameter | All cases | Study group | p |

|---|

| Female to male ratio | 2.94 | 2.90 | >0.05 [χ2 test] |

| Mean age | Overall | 40.16 | 39.71 | >0.05 [t-test] |

| Female | 39.1 | 38.96 |

| Male | 43.3 | 41.91 |

Mean of the responses to questionnaire obtained from different surgeons was calculated and has been shown in [Table/Fig-2].

Parmeter response and diffculty response score.

The demography and findings of clinical examination have been presented in [Table/Fig-1,3].

History and physical examination findings on first visit.

| Variable | Overall | Female | Male |

|---|

| Body mass index [mean]* | 22.97 | 22.78 | 23.53 |

| Hypertension [n] | 8 [6.4%] | 7 | 1 |

| Diabetes [n] | 34 [27.2%] | 21 | 13 |

| Pre-operative scar [n]# | 19 [15.2%] | 19 | 0 |

| ≥3 previous episodes [n]** | 79 [63.6] | 57 | 22 |

| Duration of ≥6 months from 1st episode of pain [n]## | 56 [44.8] | 42 | 14 |

| Duration of ≥3 months from last episode of pain [n]@ | 84 [67.2%] | 62 | 22 |

| Hospitalization due to cholecystitis [n] | 18 [14.4%] | 17 | 1 |

| Duration of previous hospital stay [days, mean] | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4 |

| Time since discharge [weeks, mean] | 10.1 | 12.5 | 3 |

| Icterus [n] | 2 [1.6%] | 2 | 0 |

| Palpable GB [n] | 2 [1.6%] | 1 | 1 |

| Murphy’s sign [n] | 4 [3.2%] | 4 | 0 |

| Emergency surgery [n] | 2 | 1 | 1 |

[*91.2% have BMI in normal range. #13 Pfannenstiel, 3 infra-umbilical midline, 3 umbilical. **Average number of previous episodes 3.8. ##Average duration since 1st episode 7.3 months. @Average duration since last episode of pain 4.13 months.

The cases from five surgeons who had requisite experience of laparoscopic surgery were included in the study. All the LCs was done using 12 mmHg of capnoperitoneum and an average of 144.7 litres of CO2 was used. Harmonic scalpel was the major energy source used [84.8%] followed by the bipolar. The operative findings are tabulated in [Table/Fig-4].

| Operative Findings | Overall | Female | Male |

|---|

| Contracted GB | 7 [5.6%] | 6 | 1 |

| Cystic duct not visualized initially | 7 [5.6%] | 5 | 2 |

| CBD not visualized initially | 5 [4%] | 4 | 1 |

| Adhesions of GB to anterior abdominal wall | 9 [7.2%] | 5 | 4 |

| Adhesions of GB and omentum | 92 [73.6%] | 66 | 26 |

| Adhesions of GB to bowel | 17 [13.6%] | 13 | 4 |

| Adhesion of omentum over Calot’s triangle | 22 [17.6%] | 13 | 9 |

| Adhesions of bowel over Calot’s triangle | 1 [0.8%] | 1 | 0 |

| Adhesions of liver to anterior abdominal wall or diaphragm | 28 [22.4%] | 20 | 8 |

| Adhesionsof bowel to anterior abdominal wall | 1 [0.8%] | 0 | 1 |

| Adhesions of omentum to anterior abdominal wall or falciform ligament | 13 [10.4%] | 12 | 1 |

| Narrow cystic duct and CBD angle [<40°] | 4 [3.2%] | 3 | 1 |

| Frozen Calot’s triangle | 13 [10.4%] | 10 | 3 |

| Multiple/ abnormal vessels | 4 [3.2] | 4 | 0 |

| Bile spillage | 56 [44.8%] | 39 | 17 |

| Stone spillage | 15 [12%] | 11 | 1 |

| Injury to CBD | 1 [0.8%] | 1 | 0 |

| Injury to cystic artery | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bleeding due to injury to minor vessels | 55 [44%] | 36 | 19 |

| Difficult GB removal due to frozen bed/ cystic plate | 8 [6.4] | 5 | 3 |

| Bleeding from GB bed | 21 [16.8] | 12 | 9 |

| Conversion to open surgery | 8 [6.4%] | 6 | 2 |

| Mean duration of surgery [minutes] | 100.56 | 100.75 | 100 |

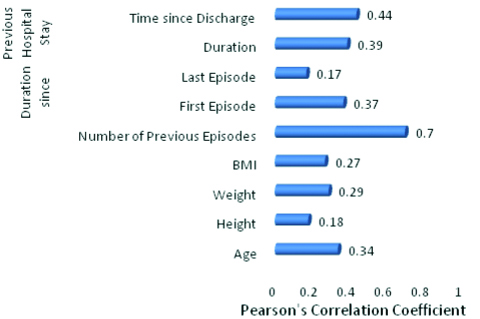

Mean WDS was found to increase with age (r=0.343, p<0.004), however gender was not significantly associated (male=15.6, female=13.6, p=0.404). A significant difference in WDS was found between hypertensive (22.6) and non-hypertensive (17.2) patients (p=0.030) as well as in diabetic (20.6) and non-diabetic (11.7) patients (p<0.001). Height (r=0.183, p=0.041), weight (0.298, p=0.001) and BMI (r=0.266, p=0.003) of the patients were also significantly associated with WDS. Difference of WDS between patients with (16.5) and without (13.7) previous operative scar was insignificant (p=0.316). Number of previous episodes of cholecystitis [r=0.701, p<0.001], duration since first episode of pain (r=0.369, p<0.001), a history of hospitalisation due to cholecystitis (WDS=25.6 and 12.1 in hospitalised and non-hospitalised patients, p<0.001) as well as duration of hospital stay [r=0.390, p<0.001] and time since discharge [r=0.437, p<0.001] were also positively and significantly correlated with WDS [Table/Fig-5,6]

Correlation Coefficient of preoperative clinical parameters.

Significance of correlation of various clinical parameters in predicting difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy [in descending order].

| Parameter | Statistical association | r | p-value |

|---|

| Number of previous episodes of pain | Significant | 0.701 | <0.001 |

| Time since discharge from hospital | Significant | 0.437 | <0.001 |

| Previous hospitalization for acute cholecystitis | Significant | - | <0.001 |

| Duration of stay in a hospital | Significant | 0.390 | <0.001 |

| Duration since first episode | Significant | 0.369 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | Significant | - | <0.001 |

| Age | Significant | 0.343 | <0.001 |

| Icterus | Significant | - | 0.002 |

| Body mass index | Significant | 0.266 | 0.003 |

| Palpable gall bladder | Significant | - | 0.025 |

| Hypertension | Significant | - | 0.03 |

| Duration since last episode | Insignificant | 0.172 | 0.055 |

| Elective or emergency surgery | Insignificant | - | 0.825 |

| Positive Murphy’s sign | Insignificant | - | 0.538 |

| Sex | Insignificant | - | 0.404 |

| Previous surgery | Insignificant | - | 0.316 |

[r is Pearson’s correlation coefficient, p<0.05 is taken as significant.

WDS was found to be increased with presence of icterus (38.3 and 13.7 for with and without icterus, p=0.002) and with a palpable gallbladder (32.2 for palpable and 13.8 for non-palpable gall bladder, p=0.025). However, presence (10.6) or absence (14.2) of Murphy’s sign had no significant effect on WDS (p=0.538). The difference in WDS in the setting of an emergency (15.9) or elective (14.1) surgery remained insignificant (p=0.8250) [Table/Fig-5,6].

Discussion

The availability of literature related to gallstone disease from North East India and particularly Sikkim is almost non-existent compared to that from the rest of India. In our setup, majority (70%) of the surgeries being performed are cholecystectomies [4-13]. Sikkim is a state in the lap of the Himalayas, and its usual for the patients to cover a long and time taking distance to seek specialised hospital care. It is not uncommon for them to tolerate pain and adapt to local socio-cultural practices rather than making an attempt to go out in a difficult terrain. And this reflects while doing LC as the sight of a difficult gall bladder is more than a common occurrence [7].

We found increasing age to be closely associated with difficulty in surgery. Various studies support this and have found an age more than 50 years to be associated with difficult Calot’s triangle dissection, fibrosis and adhesions [14-16]. However, not all studies have found an association between increasing age and difficult LC [17,18].

Many studies have shown that gender affected the difficulty level and ultimately the conversion risk, especially with male patients, but any such association of gender with the difficulty in surgery could not be established [15-18].

Though most of the patients in present study had their BMI in normal range, we concluded that with an increasing BMI, the difficulty score increases. As far as BMI is concerned there is conflict of results in various studies while some associate higher BMI to increased difficulty and higher rate of conversion and some not [17-22]. In another study, we found that incidence of “symptomatic” cholelithiasis increases with every increase in BMI and as the present study pointed out that the average number of episodes, the patients usually suffered before cholecystectomy was 3.8. This may well explain the increase in the difficulty score during surgery which may range from access to peritoneal cavity, presence of adhesions due to multiple episodes or thick fat laded falciform ligament obscuring the Calot’s triangle [8,23].

Both hypertension and diabetes, the common co-morbidities were found to be significantly associated with an increased risk of difficult surgery and was supported by various other studies especially in the elderly patients [18,24,25].

Contrary to the belief that a difficult surgery should be anticipated in those patients who had undergone some abdominal operation before, we did not find LC to be a difficult one in patients with abdominal scar due to previous abdominal surgery. Association of difficulty in surgery with previous abdominal surgery has also been disproved in many other studies including those by Yetkin G et al., Baki NAA et al., Bhar P et al., and Polychronidis A et al., [15,17,18,24].

In the present study, difficulty level increased with the number of previous episodes as well as with increasing time interval between first episode and surgery. A history of hospitalisation and time interval between discharge and cholecystectomy were found to be independent predictors of difficulty. Yetkin G et al., Younis KK et al., Vivek MAKM et al., and Kumar S et al., have shown that course of surgery tends to become difficult and conversion rate increases in patients with multiple previous episode [15,19,26,27]. While an association has also been found among the rising incidence of intra-operative difficulty and conversion rate and a history of hospitalisation [19,20,24,28-30].

Presence of icterus and a palpable gall bladder both predicted the surgery to be a difficult one. Baki NAA and Kumar S et al., found that patients with local signs of cholecystitis including palpable gall bladder and Murphy’s sign had a significantly longer operative time and difficult course of surgery [17,27]. Livingstone EH showed the signs of acute cholecystitis were associated with a conversion rate of 25% [31]. However, we couldn’t establish an association of difficult surgery with presence of Murphy’s sign.

Doing surgery in an emergency setting was not found to be more difficult compared to elective one in present study. Ferrarese AG et al., and Loalso C-M et al., found the difference in the difficulty level between the two settings insignificant [32,33].

Limitation

The criteria to define ease or difficulty was based on the responses obtained from various surgeons irrespective of their experiences and method (variation in number and size of ports, equipment variation etc.,) of doing it. There is scope to further refine the questionnaire and making it more objective.

Conclusion

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has established itself as one of the safest surgical procedures. The technique has been standardised and complication rate and conversion to open surgery are almost rare in experts’ hands. LC is now considered the entry level surgery for the beginners in laparoscopy. With increasing awareness and trend of litigation, it is the responsibility of the surgeon to explain all the possible outcomes post-surgery, and even more so if the surgery is difficult and no time can be better than the patient’s first visit to outdoor and conversation becomes more convincing if we can predict a difficult LC.A better planning can help save both the time and the currency, establish a better patient surgeon relationship in terms of complications and in case conversion to open surgery occurs.

[*91.2% have BMI in normal range. #13 Pfannenstiel, 3 infra-umbilical midline, 3 umbilical. **Average number of previous episodes 3.8. ##Average duration since 1st episode 7.3 months. @Average duration since last episode of pain 4.13 months.

[r is Pearson’s correlation coefficient, p<0.05 is taken as significant.