Introduction

In the modern educational organisation, stable conditions for the safety of students should be created [1-3]. The aim of the study is to study the satisfaction of social and psychological security at school in adolescents with intellectual disabilities [4-6].

Literature Review

Sociopsychological safety of the person is reflected in over maintaining its security or insecurity in a particular life situation when implementing social interaction with others. An important component of positive social interaction is the absence or minimisation of threats to social and sociopsychological nature that provide the subjects of interaction, a sense of psychosocial well-being, the reference importance of retaining them within the framework of normative behaviour and stimulating social activity. Security, is characterised by mutual trust, the lack of aggressiveness and malicious aspirations [2].

In Russia, mental disorders are the cause of 70% disability from childhood, 20% of children have minimal brain dysfunction [6]. Currently in Russia, psychiatric treatment consists of about 1 million people who are diagnosed with mental retardation. Of these, 39.2% are children and adolescents. The number of adolescents with intellectual disabilities has increased significantly in recent years and amounts to 5%.

Currently in Russia and abroad, the intensively developing practice of inclusive education is one of the areas which is to integrate general and special education. In recent years, many parents, in an effort to realise the right of their children with disabilities to education, ignore the recommendations of medical-psychological-pedagogical Commision and allow admittance in the mass school, losing the focus regarding sociopsychological risks and threats to inclusive education [7-20].

In case of intellectual disorders, the central nervous system cannot provide the necessary foundation for the development of personal qualities and creates obstacles that hinder the emergence of a conscious attitude to reality which is an important prerequisite for social and psychological safety and well-being of the child. Defect, exerting negative influence on social relations of the child with intellectual disabilities, complicates cognition of the surrounding world and complicates its integration into society and adaptation to it [5]. However, currently insufficient attention is paid to the creation of conditions for the formation of psychological readiness of children with intellectual disabilities to independently resolve social, communication difficulties, which significantly complicates their further adaptation and integration with the social environment.

Nazarova EN systematised current risk factors associated with inclusive and special education in Russian schools [21]. Kutepova EN described the experience of interaction between special (correctional) and general education in conditions of inclusive practice [22]. York J et al., wrote about the need to integrate students of secondary schools with disabilities into general classes [23]. Martlew M and Hodson J compared the behaviour of children with disabilities in integrated and special schools and the attitude of teachers (England) [24]. Bunch justified the need to support students with intellectual disabilities in the ordinary class (Canada) [11].

Subjective feeling of psychological well-being and security is necessary for maintaining mental health and personal integrity. It is especially necessary in the conditions of implementation of inclusive education. In the present work, we observed the developmental and traumatic nature of inclusive education [3,5,6].

Thus, inclusive education can be characterised by psychological (subjective) risks associated with the manifestation of various forms of psychological violence. According to psychologists increased anxiety of adolescents with disabilities increases their isolation, indecision, timidity, shyness, etc. Practice shows that victims of school violence are often adolescents who have physical disabilities (e.g., cerebral palsy), poor social skills (they have not developed psychological defense against verbal violence because of lack of experience and expression), deviations in the intellectual development.

Psychological violence may take the form of insults, ridicule, ignoring, etc., as a result of which a child with disabilities may developed impaired ability to adapt to the environment, which in turn can lead to the development of antisocial behaviour (victimisation, addictive, delinquent, rice wrought, aggressive etc.,) [5,20].

According to a sample survey of the quality and accessibility of educational services, 59.7% of adolescents with disabilities are fully satisfied with the safety of their stay at school and in school territory, 38.5% with the conditions of their stay, and 53.7% with the quality of the educational process. But a large number of adolescents with disabilities are not satisfied with the quality of services (gks.ru). Every fourth adolescent pointed to his insecurity at school.

On the other hand, inclusive education can contribute to the formation of sociopsychological safety of children with disabilities due to the formation of skills of social interaction, satisfaction of their needs in personal confidential communication, as well as gaining their sense of psychosocial well-being and referential importance (sense of belonging). Teachers, well-organised communicative environment may promote inclusive engagement on a personal level, which creates conditions for the adoption of normally developing children’s moral, humanistic values of compassion, empathy and tolerance in children with disabilities which lead to development of sense of referential significance and psychosocial well-being [20-24].

The question arises, in what educational environment, the child with disabilities will feel safe in the inclusive environment of mass secondary school, being trained together with normally developing peers or correctional and developmental environment of the special boarding school, learning together with peers with similar developmental disabilities?

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical code of the Russian psychological society and approved at the Russian state social University (Protocol No. 156 dated 15.12.2016). Since all teenagers were included, no sampling procedure was undertaken. The corresponding written consent was received from parents (legal representatives) of teenagers.

Psychodiagnostic examination of the questionnaire type was carried out from January 10 to February 20, 2017.

The sample included 42 pupils of the correctional school and 38 pupils of special classes of the school for children with disabilities of the College of the service sector.

Inclusion criteria includes boys and girls, aged 12-14 years, primary diagnosis of F70-mild mental retardation pupils [25].

The study was conducted on the basis of two educational institutions of Moscow which were special (correctional) boarding school number 102 and college of services number 10. The college of service sector is a mass educational institution, but has special inclusive classes, in which adolescents with a slight degree of mental retardation are trained.

Target was to compare levels of sociopsychological safety of younger adolescents with mental (intellectual) disabilities enrolled in special boarding school and junior adolescents with mental (intellectual) disabilities enrolled in special classes in mainstream educational schools.

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

For the evaluation of sociopsychological safety of adolescents with mental (intellectual) disabilities two diagnostic techniques i.e., "The scale of subjective well-being" (Perrudet-Badoux, Mendelssohn and Chiche, author’s adaptation) and "Hostility questionnaire Bass-Durk" (A. Bass, E. Durk, author’s adaptation) were used [26,27].

For statistical evaluation of differences between two samples on the level of studied parameters, we used U-Mann-Whitney test.

Results

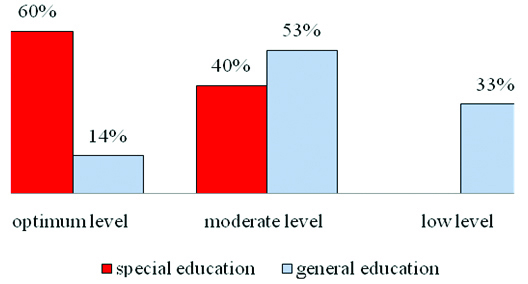

The study of subjective well-being of children with intellectual disabilities showed that 25 students (60%) of younger adolescents with intellectual disabilities studying in special school, and 5 students (14%) of younger adolescents, students in the mass school, have an optimum level of subjective well-being [Table/Fig-1].

Levels of subjective well-being of younger adolescents with intellectual disabilities enrolled in educational institutions of different types.

A moderate level of well-being revealed 16 persons (40%) of pupils in special schools and 20 persons (53%) of the students of mass schools. Such students have serious emotional problems.

A low level of subjective well-being, which is characterised by emotional instability, introversion, dependency, instability to stress, anxiety, have 14 persons (33%) of younger adolescents with mild mental retardation studying in special classes.

The comparative analysis of subjective well-being of children of the studied samples on six scales showed the results given in [Table/Fig-2].

Distribution of levels of subjective well-being in adolescents with mental retardation.

| Scale | Levels of subjective well-being, n (%) |

|---|

| Special school (n=42) | Regular school (n=38) |

|---|

| Low | Moderate | High | Low | Moderate | High |

|---|

| IS | 34 (80) | 8 (19.0) | 0 (0) | 20 (52.6) | 10 (26.3) | 8 (21) |

| PES | 31 (73.8) | 11 (26.1) | 0 (0) | 25 (65.7) | 8 (21) | 5 (13.1) |

| MC | 28 (66.6) | 8 (19.0) | 6 (14.2) | 20 (52.6) | 13 (34.2) | 5 (13.1) |

| SE | 28 (66.6) | 11 (26.1) | 3 (7.1) | 18 (47.3) | 15 (39.4) | 5 (13.1) |

| SC | 28 (66.6) | 11 (26.1) | 3 (7.1) | 20 (52.6) | 13 (34.2) | 5 (13.1) |

| DSA | 34 (80.9) | 8 (19.0) | 0 (0) | 25 (65.7) | 8 (21) | 5 (13.1) |

IS: Intensity and situations; PES: Psychoemotional symptoms; MC: Mood changes; SE: Social environment; SC: Self care; DSA: Degree of satisfaction of everyday activities

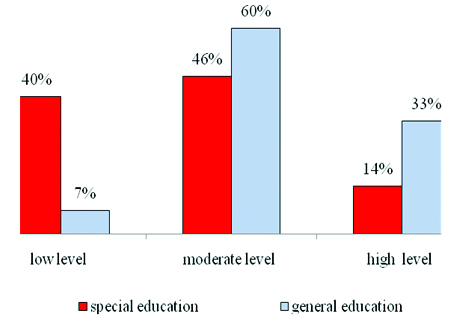

Study of hostility and aggression, children with disorders in intellect showed that 19 persons (46%) of younger adolescents with intellectual disabilities studying in special school, and 23 persons (60%) of students with intellectual disabilities enrolled in special classes in regular school, there is a medium level of hostility and 12 persons of the younger adolescents with intellectual disabilities enrolled in a hearing school and six persons (14%) of students in special schools tend to display a high level of hostility. 17 persons (40%) of younger adolescents with mild mental retardation, the level of hostility is normal. While pupils in special classes regular school, only 3 persons (7%) have a low level of hostility [Table/Fig-3].

The level of hostility of younger adolescents with intellectual disabilities enrolled in educational institutions of different types.

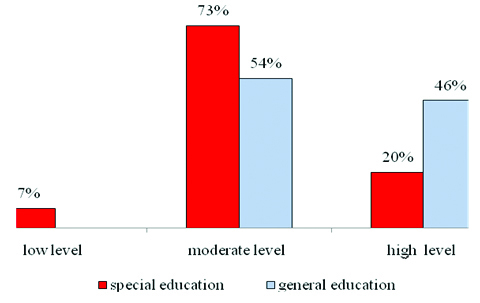

About 31 persons (73%) of younger adolescents enrolled in special school and 21 persons (54%) of students in special schools have an average level of aggressiveness. However, in mass school 17 persons (46%) of the subjects have a high level of aggressiveness, whereas in the special schools this figure is typical for 8 persons (20%). Low level of aggression typical for 3 persons (7%) of students in special schools, while in mass school the low level of aggressiveness was not detected in anyone [Table/Fig-4].

The level of aggressiveness of younger adolescents with intellectual disabilities enrolled in educational institutions of different types.

The comparative analysis of aggressiveness of children of the studied samples on six scales given in [Table/Fig-5].

The distribution of the levels of hostility and aggression in adolescents with mental retardation.

| Variables | The levels of hostility and aggression, n (%) |

|---|

| Special school (n=42) | Regular school (n=38) |

|---|

| Low | Moderate | High | Low | Moderate | High |

|---|

| PA | 25 (59.5) | 14 (33.3) | 3 (7) | 10 (26.3) | 15 (39.4) | 13 (34.2) |

| IA | 26 (61.9) | 8 (19) | 8 (19) | 18 (47.3) | 10 (26.3) | 10 (26.3) |

| I | 34 (80.9) | 8 (19) | 0 (0) | 25 (65.7) | 8 (21.0) | 5 (13.1) |

| N | 26 (61.9) | 8 (19) | 8 (19) | 15 (39.4) | 10 (26.3) | 13 (34.2) |

| O | 25 (59.5) | 17 (40.4) | 0 (0) | 18 (47.3) | 15 (39.4) | 5 (13.1) |

| S | 22 (52.3) | 14 (33.3) | 6 (14) | 15 (39.4) | 10 (26.3) | 13 (34.2) |

| VA | 31 (73.8) | 8(19) | 3 (7) | 15 (39.4) | 18 (47.3) | 5 (13.1) |

PA: Physical aggression; IA: Indirect aggression; I: Irritation; N: Negativism; O: Offense; S: Suspicion; VA: Verbal aggressiveness

Discussion

All subjects had a state of delayed or incomplete mental development, which was expressed in violation of cognitive, speech, motor and social abilities. Intellectual development is limited by a certain level of functioning of the central nervous system. Adolescents had violations not only in intelligence, but also in emotions, will, behaviour, physical development.

Based on the data obtained for the six scales for subjective well-being, we can judge about the general level of subjective well-being and emotional comfort in each group of subjects. However, the number of adolescents in the special boarding school with an optimal level of subjective well-being i.e., 25 people, was five times higher than in an inclusive school i.e., five people. Those students who feel a positive emotional comfort, can adequately control their behaviour and not inclined to voice complaints of various ailments.

One third of adolescents enrolled in special classes of inclusive school expressed emotional discomfort. They were not satisfied with themselves and their situation, lack of confidence to others and hope for the future, had difficulties in controling their emotions, unbalanced, inflexible, constantly worried about the real and imagined troubles, dependent, can not tolerate a stressful situation.

Calculation of U-criterion of Mann-Whitney showed that the level of subjective well-being of younger adolescents with intellectual disabilities studying in special school was significantly higher than in younger adolescents with intellectual disabilities enrolled in special classes in regular school (U=35.5, p≤0.01). This suggests that differences in the learning environment of younger adolescents with intellectual disabilities affect the level of their sociopsychological safety. Younger adolescents enrolled in special classes in regular school, have a distinct emotional discomfort, prone to anxiety, introverted, dependent, can not tolerate a stressful situation.

Calculation of U-criterion of Mann-Whitney showed that the level of aggressiveness of younger adolescents with intellectual disabilities studying in special school was significantly lower than in younger adolescents with intellectual disabilities enrolled in special classes in regular school (U=39.5, p≤0.01). This suggests that younger adolescents with intellectual disabilities studying in special classes in regular school are more likely to show emotional rudeness, anger against peers and adults around them. In these adolescents, there is increased anxiety, the fear of broad social contacts, egocentrism, the inability to find solutions to difficult situations, the prevalence of protective mechanisms over other mechanisms that regulate behaviour. They are not restrained in their emotional manifestations, may resort to physical force and swearing, committing themselves to destructive actions, becomes risk being in a dangerous situation. They may expose themselves to unnecessary risk, and they also tend to show hostility to the world.

Thus, the study showed that remedial and developmental environment of the boarding school are mainly provided by social psychological safety of adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Comfortable environment in a special boarding school contributes to the local formation of adolescents subjective well-being and consequently, low aggressiveness. The educational environment of public schools requires adolescents to adapt to the sociopsychological environment, which is accompanied by a display of aggression from both normally developing students and students with disabilities and, as a consequence, loss of subjective well-being.

Limitation

Limitation of the present study was that the sample of subjects consisted of adolescents with a diagnosis of F70-mild mental retardation [25].

Conclusion

The world has a wide range of publications aimed at the study of inclusive education of adolescents with disabilities. The study confirmed the problem of insufficient social and psychological conditions of inclusive education for adolescents with disabilities to feel personal safety in public school [9-20,23,24,26-29]. Teenagers with intellectual disabilities of inclusive classes of the college of services have a lower level of subjective well-being and a higher level of aggression than their peers of a special (correctional) boarding school. This may be due to the insufficient quality of work and psychological support of adolescents with intellectual disabilities in a mass secondary school and psychological and pedagogical support of inclusive education in mass Russian schools.

The recommendation is the creation of a special service and carrying out correctional and developmental work and psychological support of adolescents with intellectual disabilities in a mass secondary school.

The obtained results indicate the necessity of development and implementation in educational organisations with inclusive education, a comprehensive psychopedagogical support of social and psychological safety of children with developmental disabilities. It must create conditions to facilitate adaptation to the social environment, the development of safe social interactions, decrease aggression and the formation of social tolerance, through training and education, based on the general theory of humanisation of education, theories of psychological safety of subjects of education, special pedagogy and psychology.

Federal state educational standard for students with disabilities (particularly intellectual disabilities) provides for increased contact of students with typically developing peers and interaction with different people. This can be achieved by participation in extracurricular activities (competitions, exhibitions, creative festivals, and competition (unified sports), implementation of available projects etc. These extracurricular activity promotes social integration of students with intellectual disabilities, their self realisation and successful joint activities of all participants.

IS: Intensity and situations; PES: Psychoemotional symptoms; MC: Mood changes; SE: Social environment; SC: Self care; DSA: Degree of satisfaction of everyday activities

PA: Physical aggression; IA: Indirect aggression; I: Irritation; N: Negativism; O: Offense; S: Suspicion; VA: Verbal aggressiveness

[1]. Baeva IA, Tarasova SV, Safe educational environment: psychological and pedagogical bases of the formation, maintenance, and evaluation 2014 Saint-PetersburgLOIRO [Google Scholar]

[2]. Davydova MS, Peculiarities of forming of social notions about vital safety among children with mental disturbancesIzvestia: Herzen University Journal of Humanities & Sciences 2009 98:94-101. [Google Scholar]

[3]. Kislyakov PA, Shmeleva EA, Belyakova NV, Romanova AV, Threats to the social safety of educational environment in the Russian schools. PONTEInternational Scientific Researchs Journal 2016 72(12):355-63.10.21506/j.ponte.2016.12.28 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[4]. Matyushkova SD, Kovalevskiy RG, Social and psychological safety of children enrolled in a secondary school in the context of a therapeutic environment companiesPsychology and Social Pedagogy: Current State and Prospects of Development 2016 1:158-63. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Filippova MV, Provision of psychological security of children with intellectual disabilities in the process of educational work in the orphanage-boardingTraining and education: methodology and practice 2016 30(1):216-23. [Google Scholar]

[6]. Shmeleva EA, Pravdov MA, Kislyakov PA, Kornev AV, Psychological-pedagogical support of development and correction of psychofunctional and physical abilities in the process of socialization of children with intellectual disabilitiesTheory and Practice of Physical Culture 2016 3:41-43. [Google Scholar]

[7]. Feldstein DI, The preaching of childhood: psychological and pedagogical problems of education. Professional educationStole 2011 5:8-11. [Google Scholar]

[8]. Chernyshov MY, About inclusive education as a form of integration of education for disabled personsIntegration of Education 2013 4:84-91. [Google Scholar]

[9]. Bešic E, Paleczek L, Krammer M, Gasteiger-Klicpera B, Inclusive practices at the teacher and class level: the experts’ viewEuropean Journal of Special Needs Education 2017 32(3):329-45.10.1080/08856257.2016.1240339 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[10]. Booth T, Ainscow M, Index for inclusion: a guide to school development led by inclusive valuesIndex for Inclusion Network 2016 Retrieved from indexforinclusion.org [Google Scholar]

[11]. Bunch G, Valeo A, Student attitudes toward peers with disabilities in inclusive and special education schoolsDisability and Society 2004 19(1):61-76.10.1080/0968759032000155640 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[12]. Carrington S, Robinson R, Inclusive school community: why is it so complex?International Journal of Inclusive Education 2006 10:4-5.10.1080/13603110500256137 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[13]. Culham A, Nind M, Deconstructing normalisation: Clearing the way for inclusionJ. of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 2003 28(1):65-78.10.1080/1366825031000086902 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[14]. Handbuch Inklusion: Grundlagen vorurteilsbewusster Bildung und Erziehung. Freiburg-Basel-Wien: Herder-Verlag. 2013 [Google Scholar]

[15]. Hickey-Moody A, Turning away from Intellectual Disability: Methods of Practice, Methods of ThoughtCritical Studies in Education 2003 44(1):1-22.10.1080/17508487.2003.9525874 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[16]. Hornby G, Inclusive special education: Development of a new theory for the education of children with special educational needs and disabilitiesBritish Journal of Special Education 2015 42(3):234-56.10.1111/1467-8578.12101 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[17]. Mattson EH, Hansen AM, Inclusive and exclusive education in Sweden: principals’ opinions and experiencesEuropean Journal of Special Needs Education 2009 24(4):465-72.10.1080/08856250903223112 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[18]. Ryndak DL, Jackson L, Billingsley F, Defining school inclusion for students with moderate to severe disabilities: What do experts say?Exceptionality 2008 2:101-16.10.1207/S15327035EX0802_2 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[19]. Smyth F, Shevlin M, Buchner T, Rodríguez Díaz S, Ferreira MAV, Inclusive education in progress: policy evolution in four European countriesEuropean Journal of Special Needs Education 2014 29(4):433-45.10.1080/08856257.2014.922797 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[20]. Unianu EM, Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive educationProcedia-Social and Behavioural Sciences 2012 33:900-04.10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.252 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[21]. Nazarova NM, Systemic risk of the development of inclusive and special education in modern conditionsSpecial education 2012 3:6-12. [Google Scholar]

[22]. Kutepova EN, The experience of interaction between special (correctional) and General education in terms of inclusive practicePsychological Science and Education 2011 1:103-12. [Google Scholar]

[23]. York J, Vandercook T, Macdonald C, HeiseNeff C, Caughey E, Feedback about integrating middle-school students with severe disabilities in general education classesExceptional Children 1991 58(3):244-58.10.1177/0014402991058003071839896 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[24]. Martlew M, Hodson J, Children with mild learning difficulties in an integrated and in a special school: Comparisons of behaviour, teasing and teacher attitudesBritish Journal of Educational Psychology 1996 61:355-72.10.1111/j.2044-8279.1991.tb00992.x1786214 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[25]. International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10). 1998 [Google Scholar]

[26]. Sokolova MV, Scale of subjective wellbeing 1996 2nd edYaroslavl [Google Scholar]

[27]. Buss AH, Durkee AH, An inventory for assessing different kinds of hostilityJournal of Consulting Psycholog 1957 21:343-49.10.1037/h004690013463189 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[28]. Pawlowicz B, The effects of inclusion on general education studentsThe Graduate School University of Wisconsin-Stout 2001 [Google Scholar]

[29]. Ford Je, Educating Students with Learning Disabilities in Inclusive ClassroomsElectronic Journal for Inclusive Education 2013 3(1):2 [Google Scholar]