Synovial fluid often referred to as “joint fluid” is a viscous and mucinous substance that lubricates most of the joints [1]. Under normal conditions, a small volume of synovial fluid is present in each joint. In a large joint such as the knee, the volume of synovial fluid is estimated to be less than 5 mL [2]. Normal synovial fluid is similar to plasma in composition, thus in pathological conditions, synovial fluid examination helps to distinguish between various inflammatory and non-inflammatory conditions affecting the joint [3].

Ropes MD and Bauer W were among the first to reveal that appearance and cell count of synovial fluid helps to differentiate between various inflammatory and non-inflammatory conditions [4]. Hollander JL et al., advised the regular examination of synovial fluid and introduced the term “synovianalysis” [5].

In 1961, Hollander JL and McCarty DJ introduced polarised light microscopy to allow identification of crystals in synovial fluid [6,7]. It was subsequently shown that detection of crystals in synovial fluid may have an impact on the clinical diagnosis and treatment [8].

Shmerling RH in their study on synovial fluid analysis concluded the importance of Gram stain and culture to diagnose infective arthritis and polarised light microscopy to diagnose crystal induced arthritis [9]. However he also concluded that disease category can be gained from total and differential white cell count [10].

Thus synovial fluid analysis is a vital step in diagnosis and management of patients with arthritis and joint effusions. It is an extremely valuable procedure in making rapid and accurate diagnosis in many types of joint diseases like various inflammatory, non-inflammatory, infective and crystal induced arthritis [11]. The gross analysis (viscosity, colour and clarity), total and differential cell count, Gram’s stain, culture and crystal search using polarised light microscopy are the most valuable studies [12].

Synovial biopsy is more useful to diagnose joint diseases, however, synovial fluid examination provides an easier, non-invasive procedure, thus, rheumatologists consider synovial fluid examination as “liquid biopsy of joint” [13].

The present study intended to establish the role of synovial fluid examination in diagnosing various types of arthritis and also to evaluate correlation between gross analysis and cell count in distinguishing inflammatory and non-inflammatory arthritis and also to document the pattern of various types of arthritis.

Materials and Methods

A prospective, observational and cross-sectional study was conducted on 100 synovial fluid samples over a period of six months from November 2016 to April 2017 in the department of Pathology and Orthopedics at Rohilkhand Medical College and Hospitals, Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh, India. Institutional Ethical Committee clearance was taken.

Detailed clinical history and examination of the patients was done. After taking an informed consent from the patient, synovial fluid was aspirated by arthrocentesis. All the aspirations were done by orthopedic surgeons after taking all aseptic precautions. All the patients of any age with one or more joint effusions were included in this study. Patients with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus and with cutaneous soft tissue infections mimicking acute arthritis were excluded from the study.

Processing of the synovial fluid specimen was done within one hour in the laboratory. In case where there was a delay, the specimen was stored in a refrigerator at 4°C.

Fluids thus obtained were first grossly examined by the naked eye for total volume, colour and appearance. Viscosity of the fluid was evaluated by performing a “string test” in which a long string (4-6 cm) forms when a drop is expressed from the end of the needle.

Microscopic examination for total and differential leukocyte count was done. Total leukocyte count was done using Neubauer’s counting chamber after diluting the fluid with normal saline. Dilution was also done by Turk fluid in case of haemorrhagic aspirate. Differential leukocyte count was done by staining a dried smear of the fluid with Leishman stain. Microbiologic assays and crystal analysis were performed where clinically indicated.

A final diagnosis was then established for each patient using the reference ranges to differentiate between the different categories [Table/Fig-1] [14,15].

Reference ranges to differentiate between the different categories.

| Group | Category | Gross | Viscosity | Cell count per mm3 | % *PMNs | Other |

|---|

| I | Normal | Yellow, Clear | Normal | <200 | <25 | - |

| II | Non-inflammatory | Yellow, Clear | Normal | 200-2000 | <25 | - |

| III | Inflammatory | Yellow, Turbid | Low | 2000-50,000 | >50 | - |

| IV | Septic | Yellow,Cloudy, Purulent | Low | >50,000 | >90 | Gram stain, Positive Cultures |

| V | Crystal induced | Cloudy, Turbid | Low | 200->50,000 | <90 | Crystal present |

| VI | Traumatic | Red, Turbid | Variable | Variable | Variable | †RBCs present |

*PMN:Polymorphonuclear neutrophils, †RBC:Red blood cells

Statistical Analysis

Sensitivity and specificity was calculated for gross examination and cell count of synovial fluid analysis. Sensitivity and specificity was calculated using the formula as sensitivity=TP/TP+FN and Senstivity=True Positive/True Positive+False Negative and specificity=True Negative/False Positive+True Negative

Results

Hundred synovial fluid samples were collected. Out of 100 samples analysed, effusion was non-inflammatory in 32 (32%) cases, inflammatory in 46 (46%) cases and infective in 10 (10%) cases. Crystal induced arthritis was seen in 3 (3%) cases while 3 (3%) cases were of traumatic arthritis. Aspirate was normal in 4 (4%) cases while 2 (2%) cases were non diagnostic due to delay in transportation of sample, resulting in degeneration of the cells.

Distribution of cases based on their aetiology is given in [Table/Fig-2].

Distribution of cases with joint effusions in various diseases/pattern of various type of arthritis.

| Nature of disease | Sex wise distribution | No. of Cases | Percentage (%) |

|---|

| M | F | | |

|---|

| Osteoarthritis (OA) | 12 | 10 | 22 | 22 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) | 4 | 12 | 16 | 16 |

| Tuberculous Arthritis (TbA) | 5 | 1 | 6 | 6 |

| Septic Arthritis (SA) | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Traumatic Arthritis (TA) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Gout Arthritis (GA) | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Inflammatory Arthritis-Not otherwise specified (IA-NOS) | 28 | 2 | 30 | 30 |

| Non Inflammatory Arthritis-Not otherwise specified (NIA-NOS) | 8 | 2 | 10 | 10 |

| Normal (N) | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Non-diagnostic Aspirate (NDA) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 70 | 30 | 100 | 100 |

Joint effusion was seen in patients between 6-70 years of age with a positive predilection of osteoarthritis in elderly patients at 40-70 years of age with a median age of 58 years. Rheumatoid arthritis was more prevalent in the age group of 30-50 years with a median age of 41 years and tuberculous arthritis in the age group of 20-35 years with a median age of 30 years.

Joint effusion was seen in 30 female and 70 male patients. Osteoarthritis was more common in males while rheumatoid arthritis was more common in females [Table/Fig-2].

The most common site of aspiration was the knee joint in 90% patients. Other joints involved were ankle joint in 6% cases, wrist joint in 2% cases and 1st metatarsopharyngeal joint in 2% cases.

Details of gross and microscopic analysis of synovial fluid are given in [Table/Fig-3].

Gross and microscopic analysis of synovial fluid.

| Synovial fluid | OA | RA | TA | SA | TbA | GA | IA-NOS | NIA-NOS | NDA | N |

|---|

| Appearance | Clear (35) | 18 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 4 |

| Turbid (61) | 4 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 26 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Purulent (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Colour | Yellow (79) | 20 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 27 | 9 | 2 | 4 |

| Cloudy (18) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Red (3) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Viscosity | Normal (41) | 22 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 4 |

| Low (59) | 0 | 15 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 28 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| TLC*(cells/mm3) | 120-2300 | 2660-30,000 | 800-3160 | 60,000-78,000 | 8,000-32,000 | 4500-50,000 | 3,000-49,520 | 150-1800 | 800-2000 | <200 |

| DLC† | Polymorphs (%) | 23 | 72 | 68 | 95 | 57 | 70 | 76 | 24 | - | 62 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 68 | 26 | 28 | 05 | 33 | 22 | 20 | 67 | - | 34 |

| Mononuclear (%) | 09 | 02 | 04 | 0 | 10 | 08 | 04 | 09 | - | 04 |

*TLC:Total leucocyte count, †DLC:Differential leucocyte count

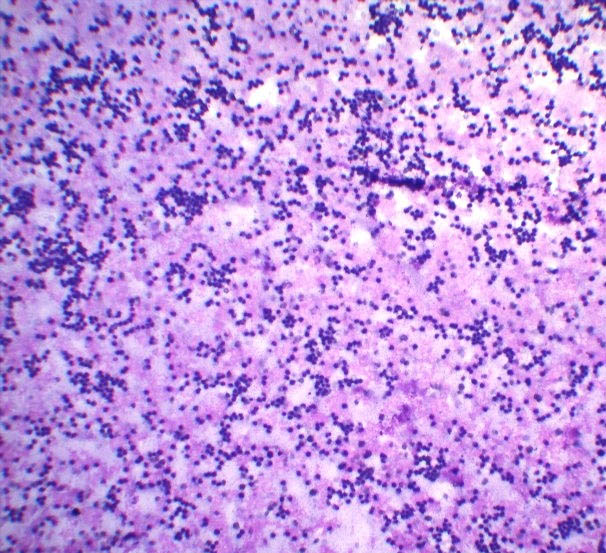

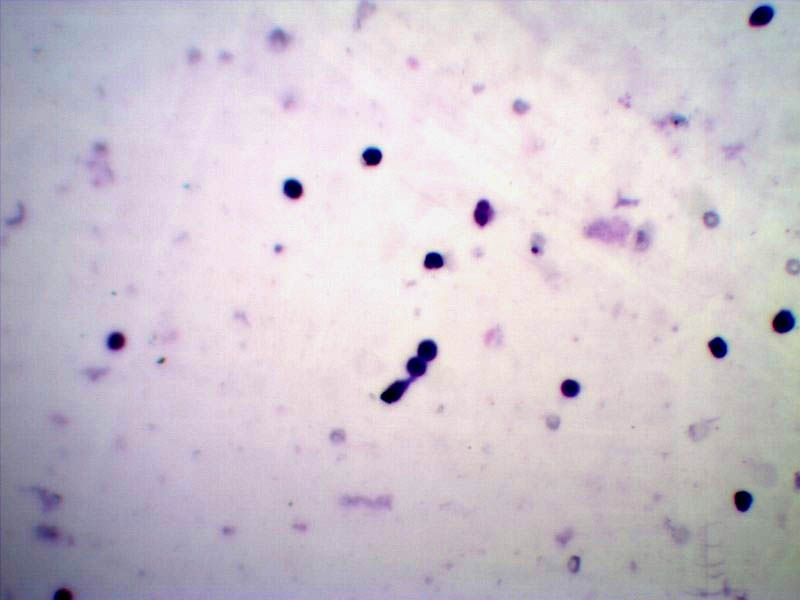

Total leukocyte count was found to be highest in septic arthritis (60,000-78,000 cells/mm3) and lowest in osteoarthritis (120-23,00 cells/mm3). Polymorphs were highest in septic arthritis (95%) [Table/Fig-4] and lowest in osteoarthritis (23%) [Table/Fig-3]. Lymphocyte count was highest in osteoarthritis (68%) [Table/Fig-5] and lowest in septic arthritis (5%) [Table/Fig-3].

Synovial fluid smears showing predominance of neutrophils. In case of septic arthritis (Leishman; 10X).

Synovial fluid smears showing predominance of lymphocytes. In case of osteoarthritis (Leishman; 40X).

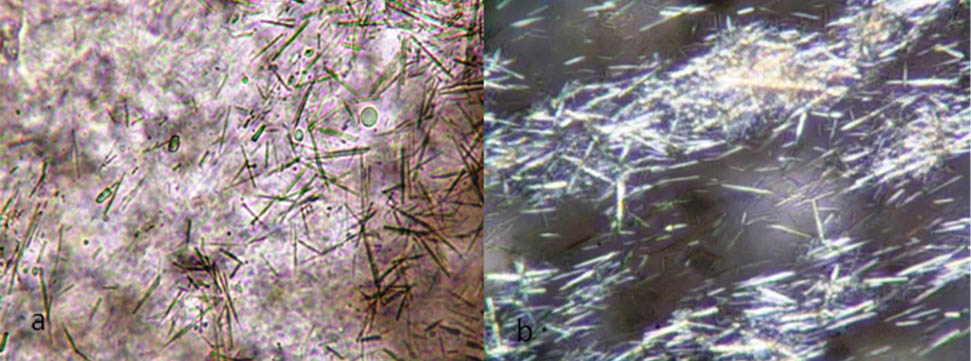

Crystal and bacteriological analysis: On wet mount preparation and under polarised microscopy numerous extracellular needles like crystals of monosodium urate were seen in 3(3%) cases [Table/Fig-6]. Culture was positive in 2(2%) cases.

Extracellular monosodium urate crystals: a) wet mount preparation in light microscopy (40X); b) polarised light microscopy (40X).

Sensitivity and specificity of gross analysis in determining whether a fluid was inflammatory or non-inflammatory was 0.91 and 0.70 respectively as compared to the cell count showing sensitivity and specificity 0.94 and 0.86 respectively.

Discussion

Synovial fluid accumulates in the joint cavity in different conditions. Analysis of synovial fluid is the gold standard in evaluation of a patient with joint effusion and in helping the clinician to determine a patient’s clinical condition and further course of treatment. The British Society for Rheumatology (BSR) and American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines recommended that gross analysis (viscosity, colour and clarity), measurement of total and differential White Blood Cell (WBC) counts, crystal analysis and microbiological assays (microscopy and culture) are the synovial fluid parameters that are collectively more effective [16,17] rather than other tests such as mucin clot test, glucose, protein and pH studies which have been shown to be less effective [10,18].

The gross examination of synovial fluid can add appropriate diagnostic information regarding the amount of joint inflammation and being of haemarthrosis. Transparent synovial fluid usually occurs in non-inflammatory conditions and the amount of turbidity increases with increase in joint inflammation. Most purulent fluid usually occurs in infected joints [19]. Similar findings were observed in the present study in which synovial fluid was yellow, clear and viscous in non-inflammatory conditions while in inflammatory conditions, it was yellow and turbid with low viscosity. In conditions like septic arthritis, synovial fluid was cloudy and purulent with low viscosity. Percy JS et al., in their study reported that synovial fluid in non-inflammatory conditions as osteoarthritis is clear and yellow with normal viscosity [20].

Gross analysis of synovial fluid in case of traumatic arthritis is also valuable. In traumatic arthritis, synovial fluid was red and turbid with normal viscosity, consistent with the study by Tauro B et al., which revealed, synovial fluid in traumatic arthritis was haemorrhagic with normal viscosity [21].

In another study of joint effusions, it was reported that increasing joint inflammation is associated with increased synovial fluid volume, reduced viscosity, increasing turbidity, increasing cell count and increasing ratio of PMN: Mononuclear cells [22]. These findings are consistent with the present study, revealing that synovial fluid, in conditions like septic arthritis having marked joint inflammation, is cloudy and purulent, having low viscosity with highest total leukocyte count ranged from 60,000 to 78,000 cells/mm3 and neutrophil predominance i.e 95%, but such changes are non-specific and must be interpreted in clinical settings.

Determination of the synovial fluid WBC count is among the most accurate tests for correctly classifying patients with joint effusions [10]. Using the synovial fluid WBC count, classification with different groups has been described, but significant overlapping limits the usefulness of this technique [9].

Osteoarthritis is the leading cause of impaired mobility in elderly [23]. In the present study total leukocyte count in osteoarthritis ranges from 120-2300 cell/mm3 which is similar to other studies which showed that count <2000 cell/mm3 is highly consistent with osteoarthritis [20].

In their study of synovial fluid analysis Yu MX reported that total leukocyte count in rheumatoid arthritis varies from 330-72600 cell/mm3, with 9-97% of polymorphonuclear leukocytes [24]. In the present study of synovial fluid analysis, total leukocyte count, observed in RA patients was 2660-30,000 cells/mm3 with polymorphs >50%. In the studies by other authors total leukocyte count in RA patients ranged from 1200-18,500 cells/mm3 with a mean of 16,000 cells/mm3 and predominance of neutrophils [5].

Septic arthritis is an emergency and need early diagnosis and treatment as it can lead to irreversible joint damage. As the clinical presentation of septic arthritis may overlap with other causes of acute arthritis, synovial fluid analysis is needed [18]. In synovial fluid examination, total cell count of > 50,000 cells/mm3 with polymorphs >90% is highly suggestive of Septic arthritis; however these findings overlap with crystalline arthritis [18,25]. According to Krey PR et al., polymorphs >90% had a sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 78% in diagnosing septic arthritis [26]. Lower synovial fluid WBC counts in patients with septic arthritis may occur in patients having disseminated gonococcal disease, peripheral leucopenia and after joint replacement [10,18].

In crystal arthropathies synovial fluid analysis can be of major diagnostic value. In gouty/crystal induced arthritis Dai L et al., reported that the total count ranges from 4500-10000 cells/mm3 [27]. In the present study the total count in gouty/crystal induced arthritis ranges from 4500-50000 cells/mm3. Gorden TP et al., found that synovial fluid with inflammatory type of changes revealing intra and extra cellular needle shaped crystals with negative birefringence on polarised light microscopy are suggestive of Gout [28], which is similar to our study.

In tuberculous arthritis, most common clinical manifestation is chronic monoarthritis. Knee joint is most commonly affected followed by ankle, wrist, shoulder and elbow. In the present study, synovial fluid examination showed total cell count in the range of 8,000-32,000 cells/mm3, with <60% of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. This is similar to the other studies in which white cell count was in the range of 7,200-30,000 cells/mm3, with 77% of polymorphonuclear leukocytes [5,20,29]. Identification of mycobacterium tuberculosis organism with ZN staining on smear is the most reliable method of establishing diagnosis [30]. However, sensitivity of the test is quite low as Steven B et al., showed that only 27% cases show positivity for acid fast organism on fluid smears [31]. In present study, all six cases were negative for tubercle bacilli on ZN staining.

In our study, comparison between gross fluid analysis test and cell count test in determining whether a fluid is inflammatory or non-inflammatory was also made. Sensitivity and specificity were 0.91 and 0.70 respectively for gross analysis of fluid and 0.94 and 0.86 respectively for white blood cell count test. In their study on synovial fluid test Robert H et al., reported sensitivity and specificity for white blood cell count was 0.84 and 0.84 respectively while in another study Abdullah S et al., reported sensitivity and specificity for gross fluid analysis test was 0.94 and 0.58 respectively [32,33].

Limitation

More studies are needed to clarify the relation between the level of synovial fluid leucocytes and the development of joint destruction in patients with inflammatory arthritis. There is also considerable interobserver and intraobserver error in the assessment of cells and identification of crystals in synovial fluid examination.

Conclusion

The synovial fluid examination is the foremost in the diagnosis and management of patient with joint diseases. Our study presents the basis of the synovial fluid analysis and a relevant decision making scheme to diagnose various types of arthritis. The need of conducting this study was to establish the role of gross analysis and cell count in quick identification of patients with inflammatory arthritis. Clearly, synovial fluid analysis is relatively under researched and generally excluded from routine diagnostic services. There is a need for further emphasis on the value of synovial fluid inspection and cell counts (as they help clinicians with diagnosis and assessment of the degree of inflammation), as well as of the specificity and sensitivity of gross examination and cytology. Without such data we will remain ignorant as to the value of synovial fluid analysis.

*PMN:Polymorphonuclear neutrophils, †RBC:Red blood cells

*TLC:Total leucocyte count, †DLC:Differential leucocyte count