Labour epidural analgesia using local anaesthetic drugs and opioids has gained widespread popularity over other techniques in modern obstetric analgesia practice. Bupivacaine provides excellent analgesia for labour and delivery but its potential for cardiovascular toxicity has prompted the search for alternative agents. Ropivacaine and levobupivacaine are suitable alternatives to bupivacaine for labour analgesia, as they are associated with less cardiovascular and central nervous system toxicity, produce less motor block, lesser incidence of instrumental deliveries and better neonatal outcome than bupivacaine [1-6].

Levobupivacaine and ropivacaine are recently introduced in Indian market and not many studies in the field of labour analgesia have been conducted in Indian population using these two drugs in intermittent bolus technique [7,8]. These studies have compared ropivacaine with bupivacaine in low concentrations for labour analgesia and they have concluded that both these drugs provide equivalent analgesia. However, studies comparing levobupivacaine and ropivacaine for labour epidural analgesia are limited in Indian population. Hence, we have conducted the present study using epidural levobupivacaine 0.1% with fentanyl 2 mcg/mL and epidural ropivacaine 0.1% with fentanyl 2 mcg/mL to compare the relative potencies and clinical characteristics in terms of onset and quality of analgesia, sensory and motor block, requirement of local anaesthetic agents, side effects, obstetric interventions, neonatal outcome and maternal satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

After approval from Institutional Ethics Committee, the present prospective, randomised, double blind study was conducted on 60 American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status I and II consenting parturients with single live full term fetus in vertex presentation, in active labour with 3 cm cervical dilatation without any obstetric complications. The study was conducted from January 2013 to June 2014. Patients were randomised using a computer generated chart into two groups (Group LF and Group RF, n=30 in each group). For labour epidural analgesia, parturients in Group LF received 0.1% levobupivacaine with fentanyl 2 mcg/mL and those in Group RF received 0.1% ropivacaine with fentanyl 2 mcg/mL in intermittent bolus doses.

Patients with Body Mass Index (BMI) >30, height <150 cm, anticipated difficult intubation, contraindications for epidural catheter placement (coagulopathies, neurological deficit, infection at the site, allergy to study drug etc.,) were excluded from the study. Out of 64 patients evaluated for the study, four patients were excluded due to obesity (1), infection at the site of epidural placement (2) and unwilling parturient (1).

For double blinding, the study solution was prepared by one qualified anaesthesiologist who was not involved in patient management and handed over to the investigator so that the parturient and investigator both were blind to the study drug.

Parturients meeting inclusion criteria were explained about the study and written informed consent was obtained. They were explained about 10 cm Visual Analog Scale (VAS), for quantification of pain at the peak of uterine contraction. Complete evaluation of demographic (age, weight, height) and obstetric (weeks of gestation, cervical dilatation, progress of labour) parameters were done. Parturients with cervical dilatation of ≥3 cm in active labour were taken inside Operation Theatre (OT) for placement of epidural catheter under strict aseptic precautions by experienced consultant anaesthesiologist. After epidural placement, all patients were monitored in supine position with wedge under the right hip and delivered in labour room adjacent to OT.

Pulse oximeter, electrocardiogram and noninvasive blood pressure monitor were connected to the patient. Baseline parameters like heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation and VAS were noted before insertion of epidural catheter. Intravenous access was secured and parturients were pre-hydrated with 500 mL of Ringer Lactate solution. Supplemental oxygen (2 litre/minute) was given by nasal prongs to all patients.

The procedure was performed using 18 G Tuohy’s needle (Epidural Minipack System 1, Portex, Smiths Medical India Pvt. Ltd.,) with parturient in sitting position. A 20 G multi-orifice catheter was placed in L3-L4 or L4-L5 inter vertebral space using loss of resistance technique and catheter tip was advanced 4 cm cephalad. A test dose of 3 mL of lignocaine 1.5% with 15 mcg Epinephrine (1:2,00,000) was administered through epidural catheter after careful aspiration to rule out subarachnoid or intravascular placement of catheter. The catheter was secured and the parturient placed in supine position with left uterine displacement. The initial dose of 10 mL study drug was administered via epidural catheter in two incremental boluses of 5 mL over 10 minutes. Pain assessment was done at peak of contraction using VAS. The study solution was administered (if VAS ≥4) in aliquots of 5 mL every 5 minutes till VAS <4 upto maximum dose of 30 mL. At the end of 60 minutes, if VAS remained ≥4 then rescue analgesia with 5 mL of 0.25% study drug was given over 10 minutes. If VAS remained ≥4 in spite of rescue analgesia, then labour analgesia was considered inadequate and the patient was excluded from further analysis.

The initial volume of study solution required to reduce VAS ≤4 was considered as loading dose and time required for same was considered as onset of analgesia.

During progress of labour, parturient was given intermittent bolus top up of 5 mL study solution at VAS ≥3. Two subsequent top ups were spaced at minimum interval of 5 minutes, with hourly limit of 30 mL. Rescue analgesia was given if VAS persisted ≥4 even after giving 30 mL of top up in an hour. Total number of top ups required were noted. During second stage of labour, drug was administered in semi-recumbent position. The epidural catheter was removed after the baby delivery.

Maternal monitoring during study included heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, sedation, VAS, sensory and motor block. After administration of drug and top up, vital parameters were noted every 5 minutes for first 30 minutes and then every 30 minutes till the end of study.

Maternal hypotension was to be considered as fall in systolic blood pressure of more than 20% of baseline value or systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg and to be treated with left lateral decubitus position, Intravenous (IV) fluids, vasopressor like ephedrine if required and administration of oxygen via facemask. Maternal sedation was assessed using modified Ramsay sedation Score (1=anxious, restless, 2=cooperative, tranquil, 3=responding to commands, 4=brisk response to light glabellar tap, 5=sluggish response to light glabellar tap, 6=No Response). Analgesia was assessed using the 10 point VAS score where 0 represented “no pain” and 10 represented “worst pain”. Sensory block was assessed every 30 minutes by loss of cold sensation to ether swab. Motor blockade was assessed at 10 minutes interval using Modified Bromage scale (0=no motor block, 1=inability to raise the extended leg and ability to move knees and feet, 2=inability to raise the extended leg and to move knees but ability to move feet, 3=complete motor blockage of lower limbs). Peak sensory level and motor block during study was noted.

Fetal monitoring included fetal heart rate which was recorded every 5 minutes for first 30 minutes, then every 30 minutes till end of study and after every top up. Neonatal welfare was assessed by Apgar score.

Obstetric interventions like instrumental deliveries (forceps, vacuum), lower section caesarean section were noted. Labour was managed as per institutional obstetric protocol and all parturients were given oxytocin.

The total dose of levobupivacaine, ropivacaine and fentanyl used and an hourly requirement of local anaesthetic were noted.

Maternal side effects like nausea, vomiting, pruritus, hypotension, respiratory depression (respiratory rate <8/minute) were noted and appropriate measures were taken. The parturient and the newborn were followed up till 24 hours for any late complications.

At the end of study, the quality of epidural analgesia was graded as excellent/good/fair/poor/absent by parturients. Maternal satisfaction was graded as excellent/good/fair/poor.

Following parturients were excluded from data analysis; persistent inadequate analgesia in spite of rescue analgesia, accidental epidural catheter removal, delivery within two hours of epidural catheter placement, study lasting for >24 hours.

Statistical Analysis

As per power analysis calculation, 25 patients in each group were calculated as appropriate sample size to detect a difference of 8 mL per hour among both groups assuming mean drug use of 20 mL/hour and standard deviation of 10. With the power of study of 80%, α-error of 0.05 and possible drop outs, 30 patients in each group were enrolled.

We enrolled 60 patients (30 in each group). Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16.0 was used for statistical analysis. (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The demographic data was analysed using Unpaired Student’s t-test for parametric data and chi-square test or Fischer’s-exact test for binary data. The difference between the groups was analysed using Student’s Unpaired t-test. All scores (Sedation score, VAS score, Bromage score, Apgar score) were represented as mean and standard deviation and analysed using Mann-Whitney U test. For categorical data, chi-square test was used. In this study, p-value less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and obstetric parameters were comparable in two groups [Table/Fig-1]. Haemodynamic parameters, sedation score, onset of analgesia, sensory level were comparable in both groups. The mean respiratory rate was 19±2.66 per minute in LF group and 20.33±2.24 per minute in RF group which was comparable. The mean SpO2 in LF group was 98.70±0.47% and 98.67±0.48% in RF group which was also comparable [Table/Fig-2,3,4 and 5].

Comparison demographic and obstetric parameters.

| Parameter | Group LF (n=30) | Group RF (n=30) | p-value |

|---|

| Age in years (Mean±SD) | 24.26±3.39 | 24.67±3.19 | 0.815 |

| Weight (kg) (Mean±SD) | 54.50±3.79 | 53.53±4.75 | 0.387 |

| Height (feet) (Mean±SD) | 5.28±0.21 | 5.34±0.27 | 0.251 |

| Gestational age (weeks) (Mean±SD) | 38.49±1.75 | 38.09±1.67 | 0.937 |

| Cervical dilation (cm) (Mean±SD) | 3.3±0.53 | 3.23±0.43 | 0.231 |

| Parity-number (%) |

| Multigravida | 15 (50%) | 15 (50%) | |

| Primigravida | 15 (50%) | 15 (50%) | |

Comparison of sedation score, onset of analgesia, VAS score, sensory level and motor block.

| Parameter | Group LF (n=30) | Group RF (n=30) | p-value |

|---|

| Sedation score | 1.5±0.51 | 1.46±0.51 | 0.798 |

| Onset of analgesia (minutes) | 14.33±3.88 | 15±4.35 | 0.534 |

| Mean VASEnd of 1st stage | 2.6±0.93 | 2.3±0.87 | 0.200 |

| Mean VASEnd of 2nd stage | 1.86±1.04 | 2.2±0.76 | 0.08 |

| Sensory level-number (%) |

| T8 | 10 (33.3%) | 10 (33.3%) | |

| T10 | 20 (66.7%) | 20 (66.7%) | |

| Motor block |

| Grade 0 | 30 (100%) | 29 (96.7%) | |

| Grade 1 | 0 | 1 (3.33%) | |

Comparison of duration of labour in both groups.

| Duration of labour (Mean±SD) | Group LF (n=30) | Group RF (n=30) | p-value |

|---|

| 1st stage (hours) | 4.76±2.26 | 4.62±0.97 | 0.56 |

| 2nd stage (minutes) | 23.92±10.12 | 23±9.34 | 0.725 |

Comparison of maternal systolic blood pressure (mmHg).

| Time duration | Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | p-value |

|---|

| Group LF | Group RF | |

|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

|---|

| 0 minutes | 119.27 | 7.89 | 120.67 | 11.05 | 0.67 |

| 5 minutes | 115.73 | 8.98 | 118.4 | 9.16 | 0.23 |

| 10 minutes | 112.8 | 9.52 | 116 | 9.45 | 0.197 |

| 15 minutes | 112.93 | 6.80 | 115.53 | 8.29 | 0.19 |

| 30 minutes | 117.13 | 6.16 | 116.27 | 8.92 | 0.66 |

| 1 hour | 117.86 | 7.51 | 121.53 | 9.83 | 0.11 |

| 1.5 hours | 119.33 | 10.63 | 118.33 | 8.35 | 0.3 |

| 2 hours | 118.6 | 7.31 | 121 | 9.13 | 0.26 |

| 2.5 hours | 119.2 | 8.78 | 121.93 | 6.29 | 0.17 |

| 3 hours | 119.8 | 8.49 | 122.4 | 7.30 | 0.209 |

| 3.5 hours | 120.13 | 9.41 | 119.93 | 5.76 | 0.921 |

| 4 hours | 118.14 | 8.67 | 120.43 | 7.08 | 0.285 |

| 4.5 hours | 119.83 | 8.42 | 117.76 | 6.67 | 0.405 |

| 5 hours | 117.28 | 8.61 | 120.81 | 7.87 | 0.263 |

| 5.5 hours | 118.45 | 6.70 | 122.85 | 5.14 | 0.064 |

| 6 hours | 116 | 8.88 | 121.6 | 2.60 | 0.203 |

| 6.5 hours | 113.66 | 5.85 | 118 | 5.29 | 0.524 |

| 7 hours | 118.33 | 9.51 | 108 | 4.61 | 0.36 |

| 7.5 hours | 112.5 | 5 | 124 | 6.11 | 0.132 |

| 8 hours | 114.67 | 9.24 | 106 | 9.23 | 0.502 |

| 8.5 hours | 120 | 2.83 | 110 | 2.82 | 0.212 |

Comparison of maternal heart rate.

| Time duration | Heart rate (per minute) | p-value |

|---|

| Group LF | Group RF |

|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

|---|

| 0 minutes | 100.87 | 10.46 | 100.07 | 10.37 | 0.058 |

| 5 minutes | 92 | 11.46 | 95.93 | 8.86 | 0.145 |

| 10 minutes | 91.38 | 10.49 | 90.8 | 8.46 | 0.816 |

| 15 minutes | 92.4 | 9.70 | 90.27 | 7.31 | 0.34 |

| 30 minutes | 94.47 | 8.83 | 93.6 | 10.73 | 0.734 |

| 1 hour | 94.07 | 7.92 | 94.47 | 8.16 | 0.848 |

| 1.5 hours | 92.07 | 7.45 | 89.4 | 7.05 | 0.61 |

| 2 hours | 95.33 | 10.08 | 91.07 | 7.33 | 0.066 |

| 2.5 hours | 96.93 | 9.54 | 94.67 | 7.11 | 0.301 |

| 3 hours | 94.6 | 8.44 | 94.6 | 8.90 | 0.960 |

| 3.5 hours | 92.47 | 6.14 | 89.4 | 6.95 | 0.641 |

| 4 hours | 91.86 | 8.02 | 90.86 | 6.67 | 0.614 |

| 4.5 hours | 93.09 | 7.99 | 88.67 | 7.13 | 0.076 |

| 5 hours | 91.57 | 8.85 | 91.86 | 10.27 | 0.938 |

| 5.5 hours | 88.55 | 7.43 | 94.25 | 4.33 | 0.07 |

| 6 hours | 93.5 | 9.61 | 92.4 | 10.43 | 0.849 |

| 6.5 hours | 92.33 | 7.42 | 110 | 8.26 | 0.079 |

| 7 hours | 95 | 7.77 | 98 | 4.12 | 0.735 |

| 7.5 hours | 95.5 | 5.26 | 108 | 4.61 | 0.124 |

| 8 hours | 96.67 | 8.08 | 96 | 8.08 | 0.950 |

| 8.5 hours | 95 | 7.07 | 92 | 7.07 | 0.788 |

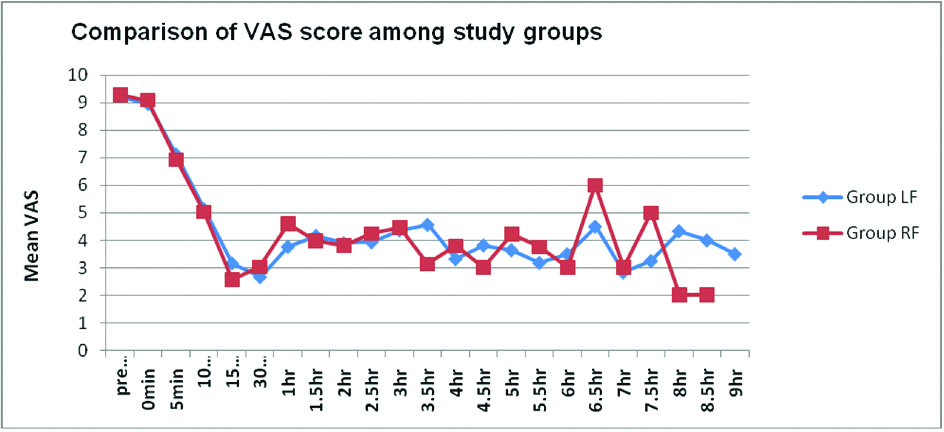

The baseline mean VAS scores were comparable (9.23±0.81 in LF group, 9.3±1.26 in RF group). There was a fall in VAS score in both the groups after onset of analgesia in first 15 minutes, thereafter VAS score remained stable and comparable in both the groups [Table/Fig-6,7].

Profile of mean visual analog score.

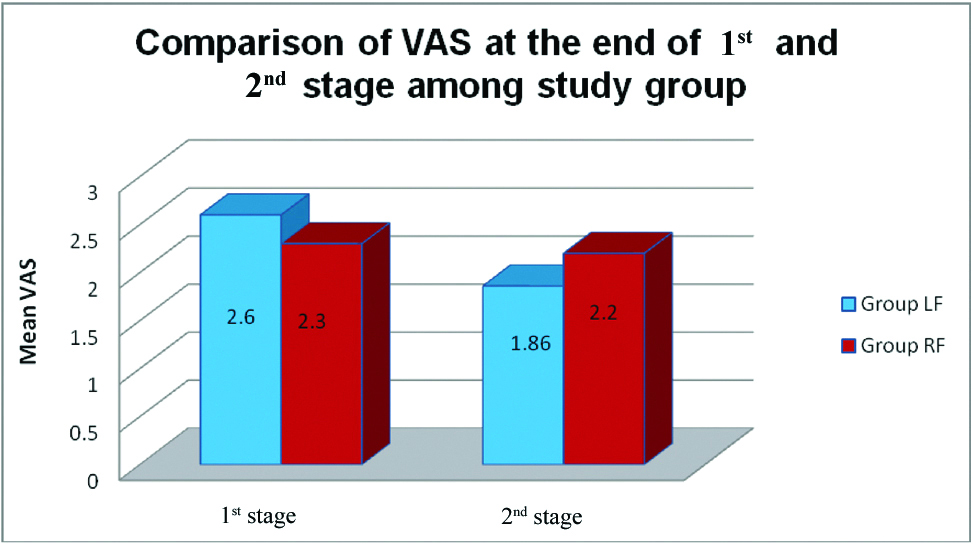

Profile of mean visual analog score in both groups at the end of 1st and 2nd stage of labour.

One parturient (3.33%) in RF group developed motor block of Bromage Grade 1 as compared to none in LF group. However, it was statistically not significant.

The mean requirement of levobupivacaine (LF) was 8.08±2.24 mg/hr and that of ropivacaine (RF) was 8.73±1.73 mg/hour, which was comparable. The mean requirement of fentanyl, loading dose and bolus top up was also comparable in both the groups [Table/Fig-8].

Comparison of dose of levobupivacaine, ropivacaine and fentanyl.

| Parameter | Group LF (n=30) | Group RF (n=30) | p-value |

|---|

| Dose of LA (mg) | 41.5±10.09 | 41±9.41 | 0.843 |

| Total dose LA (mg/hour) | 8.08±2.24 | 8.73±1.73 | 0.218 |

| Total dose fentanyl (mcg) | 83±20.19 | 82±18.82 | 0.8 |

| Loading dose (mg) | 14.33±3.88 | 14.5±3.04 | 0.854 |

| Top up doses (mg) | 5.43±1.77 | 5.23±1.67 | 0.655 |

None of the parturients required Rescue analgesia.

Mean duration of first stage of labour was 4.76±2.26 hours in LF group and 4.617±0.97 hours in RF group (p=0.56). Mean duration of second stage of labour was 23.92±10.12 minutes in LF group and 23±9.34 minutes in RF group (p=0.725) which was comparable.

In the LF group, quality of analgesia was excellent in 18, good in 11 and poor in 1 parturient. In the RF group, quality of analgesia was excellent in 19, good in 7 and fair in 4 parturient. The overall quality of analgesia was comparable in both groups (p=0.11).

In LF group, 2 (6.67%) parturients required forceps application and Lower Segment Caesarean Section (LSCS) was performed in 2 parturients in view of deep transverse arrest and non progress of labour. Remaining 26 (86.67%) had spontaneous vaginal delivery. In RF group, 2 (6.67%) parturients required forceps application for delivery while remaining 28 (93.33%) had spontaneous vaginal delivery. However, the overall effect of the two drugs on the mode of delivery was not significant (p=0.22).

During the present study, fetal parameters like fetal heart rate and Apgar score were also comparable in both the groups. The baseline mean fetal heart rate was 144.53±7.08 in LF group and 146.93±6.93 in RF group (p=0.169). There was no extreme variation in fetal heart rate in either group and fetal heart rate remained stable. The Apgar score at the 1 minute was 9 in all newborns in both the groups and the Apgar score at the 5 minute and 10 minute was 10 in all newborns in both the groups.

None of the parturient in either group developed any adverse effects like nausea, hypotension, pruritus or respiratory depression.

One parturient in Group LF, requiring forceps application expressed dis-satisfaction with labour analgesia while remaining parturients in both groups were satisfied with labour analgesia and it was comparable (p=0.11).

Discussion

In the present randomised, prospective, double blind study we compared 0.1% levobupivacaine with 2 mcg/mL fentanyl and 0.1% ropivacaine with 2 mcg/mL fentanyl for extradural analgesia in labour.

Clinical studies comparing levobupivacaine and ropivacaine suggest that they are equipotent in terms of clinically meaningful endpoints like drug usage, pain scores and side effects. Purdie NL et al., concluded that 0.1% ropivacaine with 0.0002% fentanyl and 0.1% levobupivacaine with 0.0002% fentanyl are clinically indistinguishable for labour analgesia in terms of onset time, duration and quality of analgesia, motor and sensory blockade, local anaesthetic consumption, mode of delivery, neonatal outcome or maternal satisfaction and appear pharmacologically equipotent when using Patient Controlled Epidural Analgesia (PCEA) [9].

We selected intermittent top-up technique for uniform spread of local anaesthetics in the epidural space leading to superior quality of analgesia allowing patient mobility whenever required. Various studies demonstrated less drug consumption in intermittent top-ups versus continuous infusion [10,11].

All parturients in the present study were induced with oxytocin. Demographic and obstetric parameters were comparable between two groups. Haemodynamic parameters, respiratory rate, sedation score and oxygen saturation were comparable in both groups. Similar results were observed by Benhamou D et al., who did a sequential allocation study with initial concentration of 0.11% levobupivacaine and 0.11% ropivacaine and Purdie NL et al., [9,12].

The duration of first and second stage labour was comparable between two groups without any statistical significance (p=0.725). Our results are comparable to Beilin Y et al., who did a comparative study using 0.0625% of the LA (bupivacaine, levobupivacaine or ropivacaine) with fentanyl 2 mcg/mL [13].

We found that the average onset of analgesia was comparable in both groups. The mean time required to achieve VAS score <4 was 14.33±3.88 minutes in group LF and 15±4.35 minutes in Group RF (p=0.53). Purdie NL et al., also found comparable onset of analgesia with loading dose of 15 mL in levobupivacaine and ropivacaine group {38 (19-51) minutes, 30 (15-45) minutes respectively} [9].

The profile of VAS score was comparable in both the groups throughout the study. The mean VAS at the end of first stage was 2.6±0.93 in Group LF and 2.3±0.87 in Group RF (p=0.2003). The mean VAS at the end of second stage was 1.86±1.04 in Group LF and 2.2±0.76 in Group RF (p=0.08). VAS Scores correspond with the analgesic potential. Similar pain scores in both groups in first and second stage of labour suggest that levobupivacaine and ropivacaine in concentration of 0.1% along with fentanyl 2 mcg/cc are equi-analgesic. The present results are comparable with Purdie NL et al., who concluded that verbal pain scores were similar between groups before and after local anaesthetic administration, and were comparable throughout the study [9]. Various other studies done by Polley LS et al., and Sah N et al., have also found comparable profile of VAS scores between levobupivacaine and ropivacaine [14,15].

In LF group, quality of analgesia was rated as excellent by 18 parturients and good by 11 parturients. However, one parturient rated it as poor which may be attributed to forceps application. In the RF group, quality of analgesia was rated as excellent by 19 parturients, good by 7 and fair by 4 parturients. The overall quality of analgesia was comparable between both groups.

We found that the mean total dose of levobupivacaine and ropivacaine was 41.50±10.09 mg and 41±9.41 mg respectively (p=0.843). Local anaesthetic requirement in mg/hour in LF and RF groups was 8.08±2.24 and 8.73±1.73 respectively (p=0.218).

Multiple studies have demonstrated that total drug requirement and mg/hour drug requirement was similar for Levobupivacaine and ropivacaine in labour epidural analgesia [9,13,14,16].

In the present study the mean total dose of fentanyl was 83±20.19 mcg in LF group and 82±18.83 mcg in RF group (p=0.843), which was comparable.

A sensory level of T8 was achieved in 10 parturients in each group and remaining 20 parturient in each group had a sensory level of T10. The present results were comparable with Sah N et al., who did this study to compare the analgesic efficacy of local anaesthetics (0.125% bupivacaine, 0.125% levobupivacaine and 0.2% ropivacaine) with fentanyl in labour epidural analgesia. They found that a mean sensory level of T10 was adequate to maintain analgesia throughout the duration of labour. They also observed a similar distribution of the sensory level in all three groups [15].

In the present study one parturient (3.33%) in RF group had a motor blockade of Grade 1 as assessed by Modified Bromage scale. None of the parturient in LF group had any motor block however this difference was not statistically significant. The present results were comparable with Sah N et al., who found no significant difference in Bromage scores on comparing the three local anaesthetics (bupivacaine, levobupivacaine and ropivacaine) [15].

Multiple other studies by Purdie NL et al., Benhamou D et al., and Polley LS et al., have found no significant difference in sensory and motor blockage between ropivacaine and levobupivacaine when used in low concentrations [9,12,14].

In the present study, two women (6.67%) in RF group were delivered using forceps; remaining 28 (93.33%) women had spontaneous vaginal delivery. In LF group, caesarean section was performed in two parturients (in one patient due to deep transverse arrest and in second parturient due to non progress of labour) and two parturients required Forceps for delivery (13.33%). Remaining 26 parturients had spontaneous vaginal delivery (86.67%). However, no statistical significance was found on comparing mode of delivery in both the groups (p=0.67). Similar results were also obtained by Beilin Y et al., who compared 0.0625% of LA with fentanyl 2 mcg/mL and found no significant difference in the operative delivery rate (bupivacaine=46%, ropivacaine=39%, and levobupivacaine=32%, P=0.35) among groups [13]. Studies done by Sah N et al., Purdie NL et al., also found no significant effect on the mode of delivery [9,15].

High success rate of spontaneous vaginal delivery in the present study could be attributed to lower (0.1%) concentration of ropivacaine and levobupivacaine producing lesser degree of motor block leading to more active participation in labour.

In the present study, neonatal baby weight was 2.71±0.24 kg in LF group and 2.74±0.215 kg in RF group (p=0.515). The Apgar scores in both the groups were comparable without any neonatal depression. Benhamou D et al., Purdie NL et al., Beilin Y et al., from their studies using low concentration of levobupivacaine and ropivacaine with fentanyl also found no adverse effect on neonatal outcome [9,12,13].

The profile of side effects was comparable between both groups. None of the parturient experienced any side effects including pruritus, vomiting or hypotension. No parturient required urinary catheterization in either group. Hence, in the present study both groups had similar safety profile.

All the parturients in both the groups were satisfied with epidural labour analgesia, with comparable results between two groups. The present findings are similar to Purdie NL et al., who found that patient satisfaction were similar between groups [9].

Limitation

The limitation of the present study was, we have not studied the efficacy of these two drugs in high risk parturients with ASA status III and IV. Further studies in such patients are recommended.

Conclusion

The combinations of low concentration (0.1%) of epidural levobupivacaine and ropivacaine with fentanyl provide equivalent labour analgesia, high success rate of spontaneous vaginal delivery without significant maternal or fetal side effects.