The Deep South of Thailand is currently the site of “South East Asia’s most violent jihadist insurgency” [1]. The root of the insurgency can be traced back at least 100 years when the Malay-speaking Sultanate of Patani was annexed by Thai-speaking predominantly-Buddhist Siam (modern-day Thailand) [2]. What followed was a string of nationalist insurgencies met with government suppression [3,4], with a relatively quiet period during the 1990s. The latest wave of violence erupted in January 2004 [1], with unprecedented attacks on innocent civilians, mostly from motorcycle drive-by shootings and improvised explosive devices detonations. The violence reached the peak in 2007 with daily attacks resulting in 3 deaths per day on average. The Royal Thai Armed Forces conducted massive deployment of personnel to the region in 2008, which helped to reduce the level of violence, and 60,000 security forces remain in the region at present [5]. As of September 2016, the region (approximately 10,936.5 sq.km. in size with population of 1,972,896) has suffered more than 19,000 casualties (6,745 deaths and 12,375 injuries) from 15,896 violent events [6]. In comparison, the number of deaths in the entire duration of the troubles in Northern Ireland (late 1960s thru 1999) was only 3,568 [7]. At present, insurgent attacks are less frequent but produce higher number of casualties per attack, and appear to serve as retaliation against actions of the Thai armed forces [5]. The majority of the affected population still remain in the region, but may have moved within the region from high-risk areas to places with lower risk [8]. Therefore, the majority of those affected by the conflict can be regarded as Conflict-Affected Residents (CARs).

Psychological trauma is defined as an event out of the everyday experience that is extremely distressing, including conflict-associated violence [9]. PTSD is a disorder that develops in individuals who experience a traumatic event, with symptoms of re-experiencing the traumatic event, avoidance, hyper-arousal and reactivity, and cognition and mood symptoms [10]. Despite the large number of casualties, the conflict has received little attention from the international community [5], and the experience of conflict-associated trauma and its burden on mental health, including PTSD, among the affected population has not been described. A review of existing information can contribute to a better understanding of the affected population, help to identify the information gaps and establish an agenda for research. This review describes the conflict-associated trauma and the burden on mental health in the population affected by the South Thailand insurgency.

Materials and Methods

For this review, sources included research articles in peer-reviewed academic journals as well as in the grey literatures (articles, reports and other relevant sources) published in Thai and English languages. PubMed Online was used to search for peer-review academic journals with the key words of “Thailand” and “Insurgency”. Google Scholar was used to search for additional “grey” literatures with the key words of “Thailand” and “Insurgency” and “PTSD”. The Google Scholar search in Thai included the key words “chai daen tai” (literal translation “The Southern Border”, referring to the affected region) and “PTSD”. To ensure that the search for the grey literature was as extensive as possible, the author also conducted the same search with the Thai key words in Google and examined the top 20 results. The search was conducted in December 2016 and included sources going back 12 years (from 2004 to 2016). The author also allowed for chain-referral of information sources due to the scarce number of sources on psychological trauma associated with the particular insurgency. The author assessed the title of the articles and excluded those not related to the trauma from the South Thailand insurgency or the burden on the mental health in the population affected by the insurgency. The author then examined the content of the remaining articles and excluded articles that were not related to the review’s objective or did not include primary data collection. An approval by an ethics committee was not applicable to this review.

Results

The search yielded 16 articles [11–26], 12 of which were published in Thai language [13,16–26]. The yield included 2 articles in a PubMed-indexed journal that pertained to psychological trauma and mental health of the affected population: one article on the psychosocial impact of the insurgency among disabled soldiers and their families [12], and one article on the experience of trauma and coping methods among health care workers [11]. Most of the results of Google Scholar search in English were published articles in the field of political science (mostly conflict and terrorism studies), while the results of Google Scholar search in Thai included peer-reviewed articles journals not listed on PubMed in the fields of medicine, psychiatry, nursing and psychiatric nursing. The results of the Google search in Thai included peer-reviewed articles written in Thai, news articles, interviews, reports, and presentations.

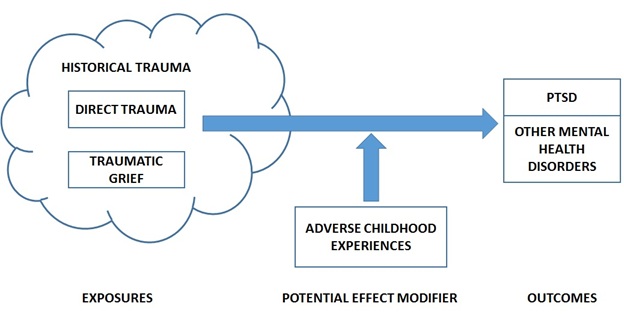

Results of the research by search tools and selection based on relevance of the articles are presented in [Table/Fig-1]. Measurement and prevalence of conflict-associated trauma and PTSD or other mental health problems in selected sources are summarized in [Table/Fig-2]. A conceptual diagram of the conflict-associated trauma and the burden on mental health in the population affected by the South Thailand insurgency can be found in [Table/Fig-3].

Results of the search by search tool and relevance of the information source.

| Category | Search yields | Title related to the objective | Content related to the objective, with primary data collection |

|---|

| PubMed-listed articles | 8 | 5 | 2 |

| Google Scholar in English | 418 | 11 | 3 |

| Google Scholar in Thai | 8 | 7 | 4 |

| Google search in Thai | Approximately 11,300 results | 15 | 7 |

Summary of measurement and prevalence of conflict-associated trauma and mental health problems in population affected by the South Thailand Insurgency in selected sources of information [11-26].

| Author | Study Design / Full Text Available / Language | Study Population | Measurement Method | Findings and Remarks |

|---|

| PubMed-listed articles |

| Thomyangkoon [11] | Cross-sectional study / No / English | n=392 hospital staff | Quality of life was measured using the SF-36 questionnaire | - Response rate was 392 of 600 questionnaires sent (65.3%)- Among those who responded, 9.9% had been directly exposed to one or more terrorist attacks and 90.1% had a family member or friend who had been exposed to terrorist attacks |

| Kumnerddee [12]” | Cross-sectional study / No / English | n=1078 traumatic cases (Royal Thai Army officers) | Mental health status of study participants was assessed using the General Health Questionaire-12 (GHQ-12) | - Approximately 51% of traumatic cases required assistance for activities of daily living (ADL)- Among the traumatic cases, mental health problems were associated with difficulties in ADL and concerns for debt repayment- Among family members of the traumatic cases, mental health problems were associated with low family income, ADL, and walking difficulty |

| Google Scholar in English |

| Panyayong [13] | Cross-sectional study / Yes / Thai | n=2884 students in 7th thru 9th grade | - Experience of trauma was assessed with 10 yes/no questions using the Psy START Rapid Triage System- Symptoms of PTSD assessed with the Revised Child Impact of Events Scale (CRIES 8)- Behavioural and emotional problems assessed with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) | - Prevalence of direct experience of violence was 9.2% - Prevalence of PTSD was 21.9% - Prevalence of behavioural and emotional problems was 37.2% |

| Wongupparaj [14] | Cross-sectional study / Yes / English | n=178 adolescents aged 15 to 24 years in Pattani Province | - Aggressive behaviour was assessed with the Aggressive Questionnaire (AQ; Buss & Perry, 1992) with 29 items on 4 domains (Anger, Hostility, Physical Aggression & Verbal Aggression)- Exposure to community violence was assessed with the modified Screen for Adolescent Violent Exposure (SAVE; Hastings & Kelley, 1997); 2 items were added to reflect the unique community context of Thailand’s Deep South | - Participants were predominantly males (85.4%), Muslims (82.0%), with secondary school education or equivalent (85.4%)- Frequent encounter with violence in the community was positively associated with accepting normative beliefs about aggression and aggressive behaviours |

| Suksawat [15] | Qualitative study / Yes / English | n=14 key informants (undergraduate students from public university with direct or secondary exposure to violence; 11 were females) | - Exposure to violence was measured using the Collective Violence Exposure Scale, adapted from the Comprehensive Trauma Inventory (CTI)- The Happiness Scale was developed from the Oxford Happiness Questionnaire (OHQ) | - Participants were initially screened using the Collective Violence Exposure Scale and the Happiness Scale, those who scored high on both Violence Exposure and Happiness (at Mean + 0.5*SD or higher in each questionnaire) were included in the study- There were four themes of collective violence among the participants:Fatally violent insurgencies (assimilation of violence from the community and the media, surviving the violence)Suffering and loss (fear / anxiety, loss of loved ones, loss of liberty and freedom, discrimination, restrained travel, loss of subsistence income, loss of educational opportunity)Physical and mental adjustments (adjusting daily routines, emotional support from social network, leisure activities, religious observations, avoiding the media)Transformation of collective violence into personal growth and maturation (acceptance of reality, having a positive attitude, understanding and compassion for others, having reduced prejudice and greater tolerance) |

| Google Scholar in Thai |

| Mahiphan [16] | Cross-sectional study / Yes / Thai | n=188 RTA personnel with children age 18 years or less) | - Concern about children was measured using a 3-point rating scale- Stress was measured using a 4-point self-assessment rating scale | - Issues of concerns included the children’s living expenses (68.6%), the children’s health (65.4%), and the children’s safety (69.7%)- Conscripts had higher level of stress than NCOs/officers (high-stress prevalence of 28% vs. 15%) |

| Prohmpetch [17] | Randomized Trial / Yes / Thai | n=140 women widowed by the unrest violence | - Posttraumatic Stress Diagnosis Scale (PDS)- Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG) | Of the 140 widows sampled from the unrest area, 105 women had symptoms of PTSD and/or complicated grief (prevalence = 75%) |

| Rukskul [18] | Cross-sectional study / Yes / Thai | n=259 soldiers in Narathiwat Province | Thailand Department of Mental Health’s Depression Screening Tool | During the first 3 months of deployment, 61.5% reported low to severe levels of stress, 34.6% screened positive for depression, 19.7% reported heavy alcohol use in past month |

| Yodchai [19] | Qualitative Study / Yes / Thai | n=21 injured victims of the bombing in Hat Yai City on 3 April 2005 (+4 caregivers), aged 18 or older | In-depth interview guidelines (experiences before, during, and after the incidence, effect on the victim and family and daily living, and coping mechanism up to the time of interview) | - The victims and family members defined the event as part of the South Thailand Insurgency, and as a mass trauma event with physical, emotional, and socioeconomic impacts. - Emotional impacts included: 1) Anger; 2) Fear and anxiety; and 3) Acceptance- The bombings happened at a shopping mall and an airport and resulted in 74 casualties (72 injured and 2 deaths) |

| Google search in Thai |

| Jampathong [20] | Cross-sectional study / Yes / Thai | n=1439 residents in the affected provinces of Songkhla, Pattani, Yala and Narathiwas | - Study instruments included: 1) World Mental Health Instrument Composite International Diagnostic Interview 3.0 (WMH CIDI 3.0) Paper and Pencil Instrument (PAPI) with 13 sections; 2) EQ-5D-5L quality of life questionnaire- The WMH CIDI 3.0 was based on ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria | - Response rate = 96.7%- Among the respondents, 11.8% had experienced conflict-related traumatic event, 8.8% of whom experienced effect on mental health and 1.3% had PTSD- Lifetime prevalence of any affective disorder = 0.8% (vs. 1.9% nationally), any anxiety disorder = 2.6% (vs. 3.1% nationally) |

| Nisoh [21] | Cross-sectional study / Yes / Thai | n=417 public health personnel at primary care hospitals in Pattani Province | - PTSD Screening Test- DS8 Suicidal Tendency Screening Instrument | - Prevalence of PTSD was 5.5%. - Among those with PTSD, 13.4% were at risk of suicide |

| Penglong [22] | Cross-sectional study / Yes / Thai | n=108 injured soldiers | - Symptom Distress Checklist 90 (SCL.90) to assess mental health status - General Health Questionnaire Plus-R (GHQ 12 Plus-R) Section 2 (PTSD Screening Test) to screen for PTSD symptoms. | - Prevalence of any mental health disorder = 73.1%- Prevalence of posttraumatic stress symptoms = 77.8% |

| Phothisat [23] | Cross-sectional study / Yes / Thai | n=214 children aged 10 to 16 years | - Psy START Rapid Triage System for unrest events data- Child Revised Impact of Events Scale-Thai version (CRIES-13) with the cut-off value of 25 points for PTSD | - Common experiences of unrest-related trauma included witnessing an unrest incident (49.5%), school being damaged (46.3%), being directly injured (45.3%), parent being injured (38.8%), not being with parent during an incident (38.8%)- Prevalence of PTSD symptoms = 18.2% |

| Songkhla Provincial Public Health Office [24] | Cross-sectional study / Yes / Thai | n=433 patients at two hospitals in Pattani | - 2P Screening Tool for PTSD - “MINI” screening tool for PTSD | - Prevalence of PTSD according to “2 P” =17.6%- Prevalence of PTSD according to “MINI” = 8.76% |

| Waiprom [25] | Cross-Sectional / Yes / Thai | n=665 RTN personnel | Instrument developed by the author | - Prevalence of history of injury = 28.2%- Prevalence of PTSD = 10.3%- Prevalence of mild depression = 39.7%, moderate depression = 6.6% |

| Yongpitayapong [26] | Cross-sectional study / Yes / Thai | n=57 students age 8 to 13 years at a public school in Pattani Province | Child Revised Impact of Event Scale-Thai version (CRIES-13) to measure PTSD | - Among the students, 19.3% had witnessed a death or injury, and 14.0% had witnessed a violent event- Prevalence of PTSD 14.0%- The study was conducted one month after the school’s director (principal) was shot to death in front of the school on 22 November 2012. |

CRIES-8 = Revised Child Impact of Events Scale; CRIES-13 = Child Revised Impact of Event Scale-Thai version; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition; GHQ 12 Plus-R = General Health Questionnaire Plus-R; ICG = Inventory of Complicated Grief; NCO = Non-Commissioned Officer; PDS = Posttraumatic Stress Diagnosis Scale; PTSD = Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; RTA = Royal Thai Army; SCL.90 = Symptom Distress Checklist 90; SDQ = Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; SF-36 = 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; WMH CIDI 3.0 = World Mental Health Instrument Composite International Diagnostic Interview 3.0

Conceptual diagram of conflict-associated trauma in the south Thailand insurgency.

Discussion

Experience of Conflict-Associated Trauma: A qualitative study among well-adjusted young adults in the affected area framed the violence into four main themes: fatally violent insurgencies, suffering and loss, physical and mental adjustments, and transformation of the violence into personal growth and maturation [15]. Using the stated framework, it is possible to categorize experience of trauma in the affected population into 3 domains, all of which are not mutually exclusive: 1) direct trauma; 2) traumatic grief / traumatic loss of loved ones, and; 3) historical trauma, which may be coupled with the sense of injustice.

Direct Trauma: Most of the casualties have been civilians who suffered from gunshot wounds and explosive blasts [27]. There were reports of forced disappearance among local residents suspected of involvement in the insurgency [3,4,28]. Prevalence of direct experience of trauma varied. The prevalence of lifetime direct experience of trauma among adult residents in the insurgency area was 11.8% [20], while the prevalence in specific groups varied from 3.5% among primary school children in Pattani Province [26] to 45.3% among children of police officers [23].

Every study used a different tool to measure exposure to trauma, but mostly consisted of questionnaire designed specifically for each study [11,14]. A number of studies used existing tools, including the START Rapid Triage System questionnaire [13], and a modified version of the Comprehensive Trauma Inventory (CTI) [15]. The experience of trauma itself is subjective, and not all cases of injury from mass casualty event are perceived by the victim as traumatic [19]. Therefore, there is a need for a descriptive study that captures the subjectivity of trauma and measures trauma in a more comprehensive manner. Such understanding will allow for a more evidence-based planning of services to address the mental health needs of the local population.

Traumatic Grief /Traumatic Loss of Loved Ones: Traumatic grief, also known as complicated grief or unresolved grief, refers to "prolonged and intense grief that is associated with substantial impairment in work, health and social functioning" [29] as a result of a death and from traumatic distress [9]. Anecdotes from the region suggested that losing male head of household due to violence leads to traumatic grief, which then affects the ability of the mother to function as the new head of household, affects the educational attainment of the children, and is likely to perpetuate the cycle of violence [30].

The prevalence of traumatic grief in the overall population of the insurgency areas has not been estimated but is likely to be high. Prevalence varies from 5.4% among middle school students [13] to 75% among women who lost their husband due to the violence and became widowed [17]. Prevalence of complicated grief in a population can be assessed by using standardized instrument, such as the Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG) questionnaire, whereas those with ICG score of 30 or higher at 6 months or more after the traumatic death are considered as possibly going through complicated grief [29]. To date, no study has assessed complicated grief in the entire affected population. Such information will provide empirical evidence to support planning of mental health services with regard to both the workload and the approach of care.

Historical Trauma Coupled with Sense of Injustice: Historical trauma refers to the trauma that a culture has experienced in the past. The trauma accumulates across time and affects people inter-generationally through anxiety, violence, and diminished social structure in the family, manifested in the forms of health problems, poverty, abuses, etc. The South Thailand Insurgency’s root goes back as far as 100 years, and given the cultural, linguistic and religious differences between Bangkok and Pattani, there were similarities between this annexation and Western-Eastern colonization. Insurgency leaders responsible for previous waves of violence (prior to 2004) are known to have "disappeared" [4]. Most of the residents in the area are of low socioeconomic status and social problems are rampant [31]. It is possible that historical trauma was directly felt by the older generations and passed onto the younger generations over this 100-year period. Massive crackdowns, particularly during the first year of the current wave of violence, may have further aggravated the existing historical trauma. The insurgents are mainly young disenfranchised Muslim men who were indoctrinated with separatist and ethno-nationalist ideologies in their childhood and subsequently recruited to join the jihad in their teens [1]. Although the Thai society at large is tolerant and accepting of Muslim people [2,3] and there have been attempts in peace negotiations between the Thai state and the insurgents, it appears that the talks cannot proceed fruitfully as long as the historical trauma and sense of injustice remain unresolved [32].

No study has assessed historical trauma in the region, thus the presence and role of historical trauma in the South Thailand insurgency remains unknown. Such assessment will provide empirical evidence that will support both planning for mental health services and efforts in peace negotiations and reconciliation between the warring parties.

Characteristics, Prevalence and Associated Factor(S) for PTSD and Mental Health Disorders in Areas Affected by the South Thailand Insurgency: Few studies characterized post-traumatic stress in details. A qualitative study among victims of a mass trauma event (bombing of shopping mall and airport in Hat Yai City, Songkhla Province) showed that the impact and stages of coping with trauma were similar to those of grief: 1) anger; 2) fear and anxiety; 3) acceptance) [19]. In a study among deployed Royal Thai Navy personnel, the most common PTSD symptoms among those injured included hyper-arousal, avoidance, and re-experiencing the traumatic event, while the least common symptom was numbing. Those with prevalent PTSD reported a sense of present danger to one’s life, witnessing dead and injured co-workers, sense of injustice (releasing arrested perpetrator of violence), and hearing news of dead and injured co-workers [25].

A non-peer-reviewed cross-sectional study of adults in affected areas found out 8.8% of adults who experienced insurgency-related trauma reported effect on mental health, and 1.2% developed PTSD [20]. However, the figure could be an underestimate due to a number of potential biases, including differential non-participation among the traumatized and those with mental illnesses, relocation, non-inclusion of all interviewed individuals, and acclimatization to the violence, and availability of locally-provided care and aid. Prevalence among various sub-groups varied from 5.5% among health personnel [21] to 75% among widows [17].

The tool used to measure PTSD symptoms varied. A number of studies used a questionnaire developed specifically for the study [21,24,25]. Other studies used existing tool. The one cross-sectional study in the general population used the World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview version 3.0 to measure prevalent PTSD, but did not describe the specific symptoms [20]. A intervention study on widows used the Posttraumatic Stress Diagnosis Scale (PDS) to measure PTSD based on three symptoms (re-experience of trauma, avoidance, and hyper-arousal) and used the Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG) to measure traumatic grief based on four symptoms (detachment from reality, inability to cope with negative emotions, inability to function, flashback or other reactions) [17]. Other studies used the Revised Child Impact of Events Scale version 8 (CRIES 8) [13] and CRIES version 13 (CRIES 13) [23,26] to report the prevalence of symptoms, but only one study directly measured PTSD [23]. The 8-items General Health Questionnaire Plus-R Part 2 was used in one study to directly measure prevalence of PTSD [22]. Some of the stated tools may have low level of sensitivity and/or specificity, affecting the validity of the measured prevalence of PTSD. Due considerations with regards to sampling methodology, measurement methods, and potential biases will allow for a more valid assessment of PTSD in the affected population.

A number of studies have reported other mental health issues among the population and population-subgroups in the affected areas [13,17,18,20,21]. Among middle school students, 37.2% had emotional and behavioural problems [13]. Among soldiers deployed to Narathiwat Province, 34.6% screened positive for depression and 19.7% reported heavy alcohol use in the past month [18]. Similar to the issue with PTSD, many of the instruments used to measure mental health disorders were self-reported screening tools, thus a well-planned study is needed to obtain more valid and comprehensive measurement of mental health disorders in the affected population.

Factors Associated with PTSD: A study among young adults in Pattani Province reported that exposure to the violence was associated with acceptance of aggressive behaviours and expressing aggressive behaviours, but the investigator did not measure PTSD among participants [14]. A study among health personnel found that PTSD was associated with using motorcycles instead of cars as mode of transportation and low level of social support [21]. A study among soldiers wounded in action showed no association between previous history of injury and PTSD, but found that PTSD was associated with age and marital status [22]. Prevalence of PTSD was not associated with any predictor among primary school students who lost their principal teacher due to a shooting one month prior [26]. On the other hand, a study in children of police officers in the unrest region showed that PTSD was associated with family relationship problems, absence of parents when the child experienced the traumatic event, and awareness that they or their families were in danger [23]. Given the high heterogeneity of factors associated with PTSD, there is a need for a study to test a priori hypothesis that will contribute to a better understanding of PTSD in the affected population, which will then contribute to better health program planning to serve the region.

Possible Effect Modification by Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) refer to stressful or traumatic event that happens to individuals before reaching the age of 18 years [33]. ACEs include physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, mother being treated violently, substance abuse within household, mental illness within household, parental separation or divorce, and incarcerated household member. Studies have found that ACEs are associated with higher risk of adverse physical and mental health, including tendency for risky behaviours including depressive symptoms, drug abuse, and antisocial behaviours [34].

In the United States, the prevalence of reporting at least one adverse childhood experience was 57% [35]. There has been no assessment of adverse childhood experience in Thailand, but a cross-sectional study on child abuse among domestic migrants showed the prevalence of 8.4%, 16.6% and 56.0% for sexual, physical and emotional abuse [36]. In other low-and-middle-income countries, the prevalence of reporting at least one adverse childhood experience was 85% in Brazil [37] and 75% in the Philippines [38], although the type of experience varied (parental separation was the most common type in Brazil, physical abuse was the most common type in the Philippines), thus it is possible that the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences in the population affected by the South Thailand insurgency would be similar to other low-and-middle income country settings. Generally, given the strong association between adverse childhood experiences on physical and mental health, there is a compelling need for nation-wide assessment of adverse childhood experiences, and that this assessment also includes the South Thailand insurgency areas.

Adverse childhood experience is known to increase the risk of PTSD. In a study among US Marines, those who reported more than one type of adverse childhood experience during recruit training were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with PTSD after coming back from deployment, particularly those who reported experiencing childhood neglect [39]. A study among a diverse group of refugees in Norway found that early-childhood potentially traumatic experiences (PTEs, a measure similar to adverse childhood experiences but with additional items pertaining to experiences of armed conflict) were more strongly related to mental health and quality of life than pre-flight war and human rights violations experiences, and that childhood PTEs were significantly associated with hyper-arousal and avoidance symptoms of PTSD [40]. A study among US troops before and after deployment to Iraq showed effect modification association between deployment and PTSD by adverse childhood experience [41].

No study has assessed the relationship between adverse childhood experience, conflict-related trauma, and PTSD in the South Thailand insurgency, but existing evidences suggest a similar pattern to the literatures. A study among middle school students in Pattani Province found that in addition to sex and exposure to violence, children who experienced death in the family and had parents who divorced also had higher odds of PTSD [13]. Similarly, a study among children of police officers also showed that having divorced parents and family relationship problems, which can be considered as adverse childhood experiences, were associated with symptoms of PTSD [23]. A good understanding of these relationships between adverse childhood experiences, war and conflict-related traumatic experiences, and PTSD will contribute to planning more effective programs to care for conflict-affected populations.

Conclusion

Trauma associated with the conflict can be divided into direct trauma, traumatic grief /loss of loved one, and historical trauma coupled with the sense of injustice. Prevalence of PTSD and mental health disorders in the insurgency area varied widely and could be subjected to biases. Future studies should consider detailed and systematic characterization of experience of trauma (including traumatic grief and historical trauma), systematic and detailed assessment of PTSD and other mental health disorders in the affected population and assess the effect modification of the association between trauma and mental health disorders by adverse childhood experiences.

CRIES-8 = Revised Child Impact of Events Scale; CRIES-13 = Child Revised Impact of Event Scale-Thai version; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition; GHQ 12 Plus-R = General Health Questionnaire Plus-R; ICG = Inventory of Complicated Grief; NCO = Non-Commissioned Officer; PDS = Posttraumatic Stress Diagnosis Scale; PTSD = Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; RTA = Royal Thai Army; SCL.90 = Symptom Distress Checklist 90; SDQ = Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; SF-36 = 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; WMH CIDI 3.0 = World Mental Health Instrument Composite International Diagnostic Interview 3.0