Acalvaria: Case Report and Review of Literature of a Rare Congenital Malformation

Deeksha Anand Singla1, Anand Singla2

1 Senior Resident, Department of Pediatrics, GMC, Patiala, Punjab, India.

2 Senior Resident, Department of Surgery, GMC, Patiala, Punjab, India.

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr. Anand Singla, F-6, Tej Bagh Colony, Near Sanauri Adda, Patiala-147001, Punjab, India.

E-mail: anand_singla84@yahoo.co.in

Acalvaria, defined as absent skull bones, is an extremely rare congenital anomaly with only a handful of cases reported in literature. Hypocalvaria is its hypoplastic variant where the skull bones are incompletely formed. Due to such a rare incidence, it has been given the status of an orphan disease. In this report we present the case of a female neonate with acalvaria born in our institute. The neonate survived a short and stormy course of 12 days as she also had associated co-morbidities. The condition per se has been described as having high mortality rate. Very few living cases, less than ten have been reported till date.

Absent skull bones, Hypocalvaria, Orphan disease

Case Report

The baby (female) was born to a 25-year-old female by non consanguineous marriage through spontaneous conception. The birth order of the baby was fifth and the only surviving sibling was a five-year-old female. The first baby was a male, born 10 years back through normal vaginal delivery who died at 1.5 months of age, the cause of death was unknown to the parents. The baby second in birth order was a still born male delivered at full term by normal vaginal delivery. The third baby was a five-year-old female child born by LSCS, who is healthy and alive. The fourth baby was a male child born by caesarean section 4 years ago, who died 22 days after birth due to congenital heart disease. This was the fifth pregnancy and a female neonate was born at 34 weeks of gestation.

The antenatal period was uneventful as per the history. The mother was receiving antenatal care at a local dispensary where basic investigations, which included, haemoglobin, HIV, HBsAg, HCV, VDRL, fasting blood sugar and urine examination were done. These investigations were normal except for maternal haemoglobin of 8g/dL. The socioeconomic and education status of the family was poor and only one antenatal ultrasound could be done in the first trimester, which was grossly normal. No other workup had been done despite bad obstetric history. She was referred to our hospital at 33±5 weeks of gestation for antenatal ultrasound which revealed no other abnormality except polyhydroamnios. The mother was admitted in view of bad obstetric history. An emergency cesarean section had to be undertaken as she developed fetal distress.

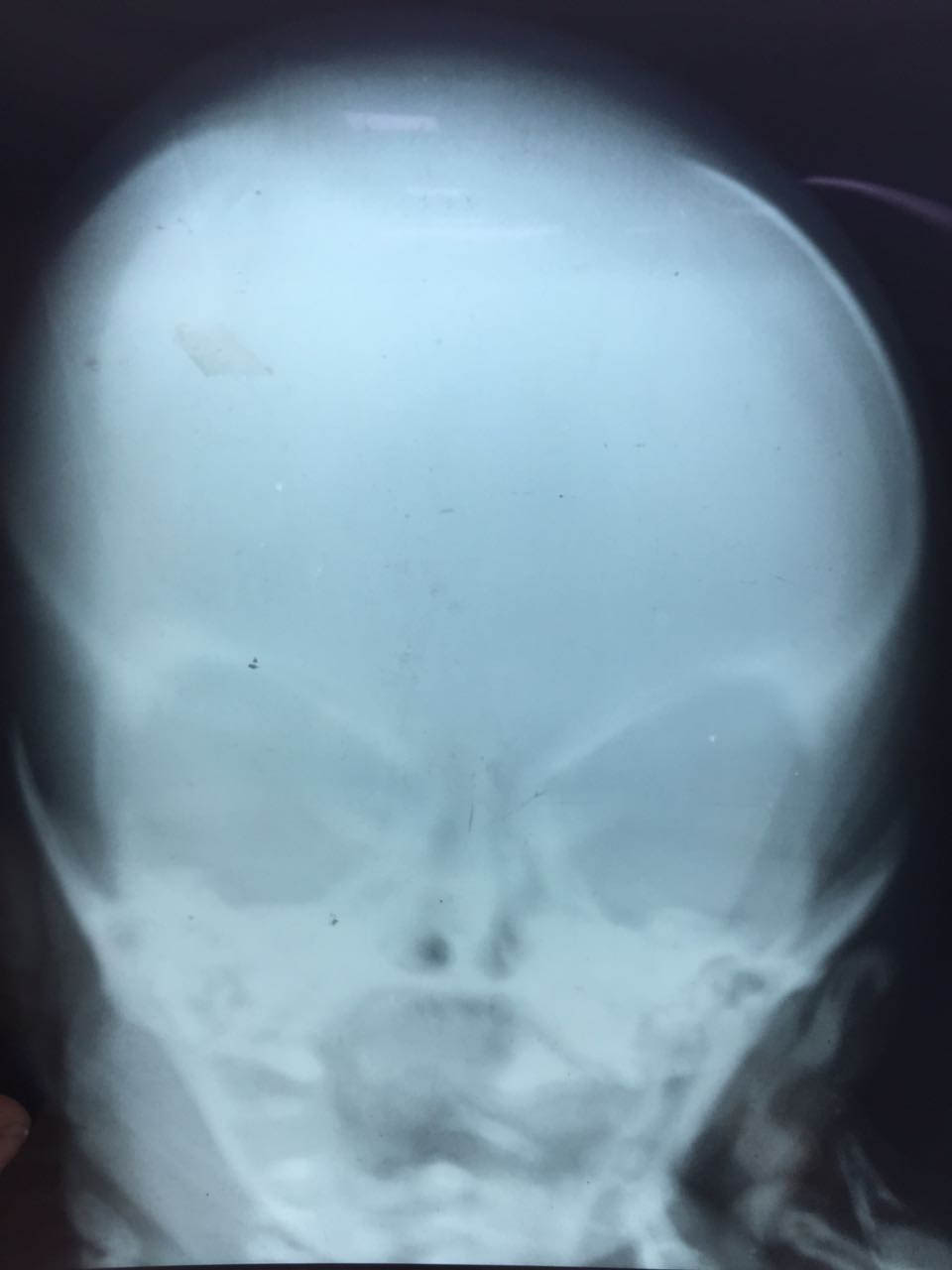

The index female neonate was born by caesarean section at 34 weeks of gestation. APGAR Score at one and five minutes was nine each. The heart rate was 142 beats per minute, respiratory rate was 66 breaths per minute with mild subcostal and intercostals retractions and no grunt. The birth weight of the baby was 2kg, length recorded was 42 cm and head circumference was 30.5 cm. Depressed nasal bridge with micrognathia were found on inspection. Eyes, ears, oral cavity and extremities appeared normal. On palpation, soft bogginess of the scalp could be felt with absent skull bones in the right parietal region, but normal frontal, temporal and occipital regions. This palpable defect in the skull was however covered with normal skin and hair. X-rays showing lack of bone in the right parietal area confirmed the presence of this defect [Table/Fig-1,2].

X-ray skull, AP view of patient showing absent parietal bone, radiolucent area instead of normal well defined bony dense shadow.

X-ray skull, lateral view showing absent parietal bone with co- incidental humeral fracture of right side.

Neurological examination revealed spontaneous eye opening, normal tone in all four limbs with active movements of the limbs. Neonatal reflexes were appropriate for gestational age and bilateral knee jerks were present. There was no evidence of any spinal dysraphism. The neonate also had a systolic murmur with normal S1 and S2 and no cyanosis. The baby had respiratory distress immediately after birth, so she was eventually shifted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) for further management.

Oxygen and fluids were initiated and lab investigations were ordered. The sepsis screen came out to be positive following which empirical antibiotics were started. Metabolic profile of the neonate revealed polycythemia with haematocrit of 62.9% which was managed with fluid and subsequently became normal. Neuroimaging and echo were also planned but could not be done due to lack of portable devices. During the stay, baby had neonatal jaundice which was treated with phototherapy. The blood culture was found to be positive for Klebsiella species. Antibiotics were upgraded accordingly and the supportive care was continued. Subsequently, the baby developed necrotizing enterocolitis as evidenced by altered aspirates and abdominal distension. It was managed with additional antibiotics and care but the neonate ultimately died on day 12 of life.

Discussion

Acalvaria is an extremely rare condition with incidence of less than 1 in 1,00,000 and has been sparingly reported in literature with only a handful of case reports [1]. Its causation is poorly understood and no concrete aetiology has been described. This disorder, showing some female predilection [2], has generally been reported as a fatal congenital malformation with only rare reports describing extended survival [3].

Acalvaria is characterized by the absence of flat bones of the skull, dura mater and associated muscles with the presence of normal cranial contents and facial bones [4]. Although some cases may show abnormal development of the brain tissue, it is usually normally developed in majority of the cases. Acalvaria can be primary or secondary, the latter being associated with open neural tube defects [4].

The aetiopathogenesis of acalvaria is essentially unknown; however its occurrence can be attributed to a post-neurulation defect during embryological development [3-5]. This implies that it results from an impaired migration of the mesenchyme (which gives rise to muscle and bone) with a normally placed embryonic ectoderm (from which skin and scalp are formed). Consequently, the brain is left covered only with an intact layer of skin with absence of calvarium [5]. There are no chromosomal anomalies reported to be associated with acalvaria, with most cases essentially being sporadic [6]. In cases associated with amniotic band, early amnion rupture is the precipitating event. The amnion may roll up like a rope entrapping the fetal head. This results in acalvaria owing to the faulty migration of the membranous neurocranium [6].

It is also important to differentiate acalvaria from acrania (absence of entire cranium) as the brain can be normal in acalvaria and can be potentially treated, but most cases of acrania eventually develop anencephaly [6].

Acalvaria has been found to be associated with a number of congenital malformations such as cleft lip and cleft palate, lung malformations, hydrocephalus [5], amniotic band syndrome [6], holoprosencephaly [7], etc. Diagnosis of acalvaria is usually possible by second trimester ultrasound after mineralization of skull bones takes place [8-10]. However, it may be detected in the first trimester also, using high resolution transvaginal ultrasonography [8] and 3D image reconstruction with ultrasound [9]. High AFP levels, although nonspecific, may help support the diagnosis of acalvaria in the setting of positive sonographic evidence [1,2].

Management of acalvaria is also not well defined as its aetiology as no two cases are same [11-13]. It has been managed well both conservatively and with extensive surgical reconstruction [1-3,11,12]. The first ever surviving case was reported 23 years back in Japan. He was a male neonate born to a primigravida mother by normal vaginal delivery. He was treated by surgical closure of the scalp defect. Also there was associated hydrocephalus so a shunt surgery was also performed. On follow up he was noted to have severe developmental delay with mental retardation [3]. He was last reported alive at the age of 11 years and was attending a special school [3].

Conservative approach has been successfully followed in patients with overlying normal scalp tissue by providing best supportive care and managing associated congenital malformations if any [1]. A two-month-old male neonate with acalvaria was managed conservatively with near normal development on follow up. The only symptom was soft skull and rest of the physical and neurological examination was normal [2].

Substantial data on surgical treatment is unavailable but reports of extensive skillful surgery by soft tissue augmentation and skin graft with excellent results have also been reported [11]. These procedures facilitate protection of duramater by soft tissue layer while maintaining a separate skin layer for future interventions. On follow up of one such successfully treated patient, near normal development and cognition have also been seen following surgery [11]. These procedures are also followed by medical and social rehabilitation to manage physical and mental disability [11-13].

Conclusion

In a nutshell, acalvaria is a fatal congenital anomaly with an extremely sinister prognosis. Vigilant diagnosis and early initiation of supportive management can significantly contribute to reduction in associated morbidity and mortality. In rare cases that may survive, surgical reconstruction, long term follow-up and rehabilitation may be essential for long-term survival and maintenance of good quality of life.

[1]. Ouma JR, Acalvaria- report of a case and discussion of literatureBr J Neurosurg 2017 4:1-2.10.1080/02688697.2017.132268528468512 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2]. Khadilkar VV, Khadilkar AV, Nimbalkar AA, Kinnare AS, AcalvariaIndian Pediatr 2004 41:618-20. [Google Scholar]

[3]. Kurata H, Tamaki N, Sawa H, Oi S, Katayama K, Mochizuki M, Acrania: report of the first surviving casePediatr Neurosurg 1996 24:52-54.10.1159/0001210158817616 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[4]. Harris CP, Townsend JJ, Carey JC, Acalvaria: a unique congenital anomalyAm J Med Genet 1993 46(6):694-99.10.1002/ajmg.13204606208362912 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[5]. Moore K, Kapur RP, Seibert JR, Atkinson W, Winter T, Acalvaria and hydrocephalus: a case report and discussion of the literatureJ Ultrasound Med 1999 18:783-87.10.7863/jum.1999.18.11.78310547112 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[6]. Chandran S, Lim MK, Yu VY, Fetal acalvaria with amniotic band syndromeArch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2000 82(1):F11-13.10.1136/fn.82.1.F1110634833 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[7]. Sperber GH, Honoré LH, Johnson ES, Acalvaria, holoprosencephaly, and facial dysmorphism syndromeJ Craniofac Genet Dev Biol Suppl 1986 2:319-29. [Google Scholar]

[8]. Yang YC, Wu CH, Chnag FM, Liu CH, Chien CH, Early prenatal diagnosis of acrania by transvaginal ultrasonigraphyJ Clin Ultrasound 1992 20:343-45.10.1002/jcu.18702005071316377 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9]. Amin MU, Mahmood R, Nafees M, Shakoor T, Fetal acrania- prenatal sonographic diagnosis and imaging features of aborted fetal brainJ Radiol Case Rep 2009 3(7):27-34.10.3941/jrcr.v3i7.27122470674 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[10]. Liu IF, Chang CH, Yu CH, Cheng YC, Chang FM, Prenatal diagnosis of fetal acrania using three-dimensional ultrasoundUltrasound Med Biol 2005 31(2):175-78.10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.10.00515708455 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[11]. Hawasli AH, Beaumont TL, Vogel TW, Woo AS, Leonard JR, AcalvariaJ Neurosurg Pediatr 2014 14(2):200-02.10.3171/2014.5.PEDS1368824926969 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[12]. Gupta V, Kumar S, Acalvaria: a rare congintal malformationJ Pediatr Neurosci 2012 7(3):185-87.10.4103/1817-1745.10647423560003 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[13]. Bang RL, Ghoneim IE, Gang RK, Al Najjadah I, Treatment dilemma: Conservative versus surgery in aplasia cutis congenitalEur J Pediatr Surg 2003 13:125-29.10.1055/s-2003-3956212776246 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]