The OST is an effective long term treatment option for opioid dependence as well as HIV prevention and intervention for opioid dependent IDUs. It is estimated that there are 1,77,000 IDUs in India [1]. The distribution of IDU population is not uniform throughout the country. As per the latest HIV sentinel surveillance report, HIV prevalence among IDUs is 7.2% nationally, which is one of the highest among any population group [1]. OST has proven effective in reducing illicit drug use, morbidity, mortality, social ormental health problems, overdose and participation in criminal activity in opioid dependent patients, thereby improving the quality of life and health of IDUs [2-7]. Opioid agonist buprenorphine which prevents opioid withdrawal symptoms and reduces craving for opioids is used as OST, also known for opioid maintenance treatment [8,9]. OST as a part of DOTS is an evidence based intervention for opioid dependent persons that replaces illicit drug use with medically prescribed, orally administered opiates such as buprenorphine and methadone. It is endorsed by United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and WHO as part of a comprehensive package of nine core interventions for IDU programs that collectively maximise impact for HIV prevention and treatment [10].

Despite being a very well structured and monitored program, all OST centers observe a high dropout rate and irregular DOTS adherence [11]. Appropriate client selection, an adequate dose of buprenorphine as well as for an adequate duration is an important determinant of a successful OST intervention. Many factors like illness representation, cognitive function, demographics, coexisting illness, medication characteristics, health system factors, provider factors, patient factors are affecting the drug adherence. The attitude of staff towards the clients, combined with other issues such as dispensing hours of the clinic, provision of ancillary services are other important determinants of the success of OST intervention [10,12].

Department of Psychiatry, having acute and chronic patient population also have patient diagnosed with substance use disorder. Patients who are opioid dependent usually come for their physical symptoms with impaired socioeconomic functioning and even they also come under influence of their peers. Department of Psychiatry is running DOST centre for opioid dependent patients for last four years. The drop-out rates of DOST centre in Surat, Gujarat, India is also high, so this study is planned to assess cognition and OST adherence in opioid dependent patients attending it.

Materials and Methods

The cross-sectional study was conducted in the DOST Centre, OPD-13, New Civil Hospital, Surat, Gujarat, India, in August 2015. And data of patient coming to DOST centre since last 1 year was collected. After approval from Human Research and Ethics committee (HREC), all patients taking OST as a part of DOTS were enrolled in this study. This study recruited 22 out of total 68 patients taking OST. Then, gradually 18 patients shifted to other OST centre, three were in prison, 17 died and eight were never followed up after first consultation. Therefore, finally we had 22 patients left for the study OST during a year of 2015. The counselor of OST program identified the subjects based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. They were referred to doctors for assessment of cognition, Comorbid medical complications, social and financial impact of opioid addiction and relation of cognition with OST drug adherence in patients with opioid dependence.

Inclusion Criteria

All patients of opioid dependence taking OST from DOST centre, who gave informed consent for the study were included.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients of schizophrenia, other psychotic disorders and bipolar mood disorder and who were on psychotropic medications and who did not give consent for the study.

A separate room was allotted for interviewing the subjects individually and in total privacy. Participant information sheet was given and informed consent was taken in their own language from all participants.

Doctors who conducted this study administered a semistructured questionnaire (based on literature search and expert consensus), which investigates qualitative and quantitative information about opioid and other substance use with related complications and assessed various domains like methods of abuse, drop out times from OST, cognition, medical comorbidities, social and financial impact of opioid addiction etc. For adherence, criteria given by National AIDS Control Organisation (NACP-IV) was used i.e., patients taking OST for <15 days, 15-25 days, >25 days per month were considered as IR, R and VR respectively [13].

Statistical Analysis

Data of adherence of patients to OST in last one year was checked from previous records kept in DOST centre. Semistructured questionnaires, Scales like ACE-III- Hindi and MMSE for cognitive assessment were used and analysed by chi-square test (for categorical variables) and ANOVA (for continuous variables) to make comparisons of characteristics between patients [14,15].

Results

Out of total 22 patients, all were males with average age of 31 years and average duration of substance use was is four year (range 1-10 years). Due to patients undergoing trial in court for legal issues, or dropping out and injecting opioids again, the days on OST decreased. A total of 15 out of 22 patients were taken to police custody with an average of 20 times arrest in their life time. A total of 11 out of 22 patients had comorbid illness, in which one had hepatitis B and 10 patients were infected with hepatitis C. Out of 365 days in a year, average duration of OST taken was 203 days [Table/Fig-1].

General description of sample.

| Total patients (males only) | (n=22) |

|---|

| Average year of age (range) | 31 (22 to 45) |

| Average duration of substance use (range) | 4 year (1-10 years) |

| Average duration of OST taken in last one year (range) | 203 days (46-360 days) |

| Number of patients taken to police custody | 15 |

| Average number of arrests in lifetime (range) | 20 times (2-50 times) |

| Comorbid illness | 11 |

| Hepatitis B | 1 |

| Hepatitis C | 10 |

Sociodemography

A total of 22 patients are involved in the present study, all were male. The five employment status categories were regrouped in two broader categories: ‘employed’ and ‘unemployed’ (unskilled/semiskilled/skilled/professional) to differentiate between active and non active members of the community. Data showed that irregularity in adherence was more in unemployed people and among patients who were illiterate. Unmarried single patients were more irregular in follow-up and people living alone or from the nuclear family, particularly the elderly were at greater risk for non adherence [Table/Fig-2]. As per modified BG Prasad classification taking five categories for Socioeconomic Class (SEC)- upper, upper middle, lower middle, upper lower and lower and regrouping them into two broader categories, upper class (upper/upper middle) and lower class (lower middle/upper lower/lower) patients from the lower SEC were more irregular. Though, statistically not significant, patient who were irregular in taking OST were unemployed, unmarried, illiterate, from nuclear family and lower SEC [Table/Fig-2].

Association between sociodemographic factors and OST drug adherence.

| Sociodemographic factors | Adherence | Total (100%) | Fisher’s-exact test | p-value |

|---|

| Irregular (<15 days) n (%) | Regular (15-25 days) n (%) | Very regular (>25 days) n (%) |

|---|

| Occupation | 9.750 | 0.210 |

| Unemployed | 6 (66.7) | 3 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 9 |

| Unskilled | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 |

| Semi skilled | 2 (28.6) | 2 (28.6) | 3 (42.9) | 7 |

| Skilled | 2 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 |

| Professional | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100) | 1 |

| Education |

| Illiterate | 8 (72.73) | 3 (27.3) | 0 (0.0) | 11 | 8.688 | 0.333 |

| Primary | 3 (33.33) | 3 (33.33) | 3 (33.33) | 9 |

| Secondary and above | 1 (50) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (50) | 2 |

| Living arrangements |

| Nuclear | 5 (55.6) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (22.2) | 9 | 3.686 | 0.888 |

| Joint | 4 (40.0) | 4 (40.0) | 2 (20.0) | 10 |

| Homeless | 2 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 |

| At Work Place | 1 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 3 (33.3) | 3 (33.3) | 3 (33.3) | 9 | 4.223 | 0.388 |

| Unmarried | 6 (75) | 2 (25) | 0 (0.0) | 8 |

| Separated | 3 (60) | 1 (20) | 1 (20) | 5 |

| Socioeconomic class |

| Upper | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (33.3) | 3 | 4.636 | 0.923 |

| Upper middle | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 0 (0.0) | 2 |

| Lower middle | 3 (37.5) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (25) | 8 |

| Upper lower | 3 (60) | 1 (20) | 1 (20) | 5 |

| Lower | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 0 (0.0) | 4 |

Other Substance Use in Last One Year

In present study population the average duration of substance use is four years with a range of one year to 10 years. Nine and 17 patients out of 22 patients also used to take alcohol and cannabis respectively.

While half of patients with cognitive decline (ACE-III score <82) were alcoholic, patients with good cognition (ACE-III score >82) were more in non drinkers group. The results of ACE-III score were consistent with MMSE score. A 2/3rd of drinkers versus 1/3rd of non drinkers were irregular. Also, overall cognitive impairment was more in patients of cannabis dependence. Thus, opioid dependent patients with alcohol use had more cognitive decline and poor adherence to OST than patients who did not use [Table/Fig-3].

Association between opioid, other substances and cognition, OST drug adherence.

| Cognition and adherence | Alcohol use n (%) | Fisher’s-exact | p-value | Cannabis use n (%) | Fisher’s-exact test | p-value | Total |

|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes |

|---|

| ACE-III |

| <82 | 8 (61.5) | 8 (88.9) | 2.440 | 0.663 | 5 (100) | 11 (64.7) | 3.601 | 0.340 | 16 |

| >82 | 5 (38.5) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (35.3) | 6 |

| MMSE |

| <24 | 6 (46.2) | 8 (88.9) | 4.313 | 0.252 | 4 (80) | 10 (58.8) | 1.921 | 0.761 | 14 |

| >24 | 7 (53.8) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (20) | 7 (41.2) | 8 |

| Adherence |

| Irregular (<15 days) | 4 (30.8) | 8 (88.9) | 7.174 | 0.229 | 3 (60) | 9 (52.9) | 2.187 | 1.000 | 12 |

| Regular (15-25 days) | 5 (38.5) | 1 (11.1) | 1 (20) | 5 (29.4) | 6 |

| Very regular (>25 days) | 4 (30.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20) | 3 (17.6) | 4 |

| Total (100) | 13 | 9 | | | 5 | 17 | | | 22 |

ACE-III: Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination-III; MMSE: Mini mental state examination

Comorbid Illness

A 50% of the patients had comorbid illness, in which one patient had hepatitis B and 10 patients had hepatitis C. No patient was found to be infected with HIV. Though, results were not significant, patients with comorbid hepatitis B and hepatitis C had poor OST adherence [Table/Fig-4].

Association between co morbid illness and cognition, adherence.ACE-III: Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination-III; MMSE: Mini mental state examination

| Cognition | Comorbid illness n (%) | Total | Fiser’s-exact test | p-value |

|---|

| Absent | Hep B | Hep C |

|---|

| ACE-III |

| <82 | 7 (63.6) | 1 (100) | 8 (80) | 16 | 1.179 | 0.735 |

| >82 | 4 (36.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (20) | 6 |

| MMSE |

| <24 | 6 (54.5) | 1 (100) | 7 (70) | 14 | 1.147 | 0.783 |

| >24 | 5 (45.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (30) | 8 |

| Adherence |

| Irregular(<15 days) | 5 (45.5) | 1 (100) | 6 (60) | 12 | 2.374 | 0.850 |

| Regular (15-25 days) | 3 (27.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (30) | 6 |

| Very regular (>25 days) | 3 (27.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10) | 4 |

| Total | 11 | 1 | 10 | 22 | | |

Cognition and Opioid Substitution Therapy Drug Adherence

In the present study, though, patients with MMSE Score <24 were higher in number in irregular group, results were statistically not significant. Taking 82 as a cut-off in ACE-III scale, comparing the adherent and non adherent group, patients who were non adherent and irregular had much lower ACE-III score; association of adherence and cognitive profile was found to be significant (p=0.032, i.e., <0.05) [Table/Fig-5]. Mean value of ACE-III in irregular patient was lower than regular patients and this result was consistent in all domains of ACE-III [Table/Fig-6].

Association between cognition and OST drug adherence in patients with opioid dependence.

| Cognition | Adherence | Total | Chi-square | p-value |

|---|

| Irregular | Regular | Very regular |

|---|

| MMSE |

| <24 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 14 | 4.714 | 0.095 |

| >24 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

| ACE-III |

| <82 | 11 | 4 | 1 | 16 | 6.875 | 0.032 |

| >82 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 |

| Total | 12 | 6 | 4 | 22 | | |

ACE-III: Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination-III; MMSE: Mini mental state examination

Association between adherence and mean value of MMSE, ACE-III, domains of ACE-III.

| MMSE | ACE-III | Memory | Language | VF | AC | VSA |

|---|

| Adherence | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Mean±SD |

|---|

| Irregular | 21.8±6.09 | 63.2±23.05 | 13.4±7.95 | 19.6±4.82 | 7.4±2.70 | 13.4±3.64 | 9.4±4.56 |

| Regular | 23.29±5.31 | 79.57±14.82 | 16.57±7.27 | 22.57±3.45 | 7.57±2.50 | 14.57±2.82 | 12.43±3.55 |

| Very regular | 22.8±4.59 | 67.9±12.08 | 12.1±4.97 | 20.7±2.49 | 5.6±2.91 | 15.2±3.04 | 8.2±3.96 |

| p-value | 0.88 | 0.007 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.58 | 0.002 |

ACE-III: Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination-III; MMSE: Mini mental state examination; VF: Verbal fluency; AC: Attention and concentration; VSA: Visuospatial ability; SD: Standard deviatiom

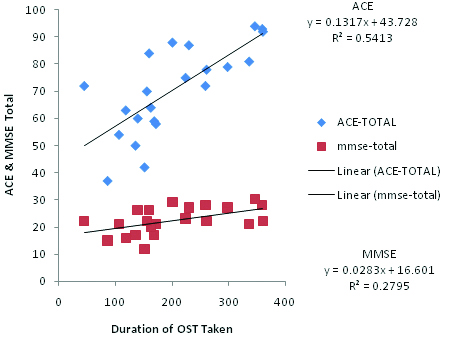

Pearson’s correlation test applied for total score of MMSE, ACE with total duration of OST taken [Table/Fig-7]. Cognition and Adherence have a statistically significant linear relationship at 0.01 level for ACE-III (p<0.001) and at 0.05 level for MMSE (p< 0.01). The direction of the relationship is positive with magnitude or strength, of the association is moderate (0.3 <| r |<0.5) for ACE-III and weak (0.1 <| r | <0.3) for MMSE.

Pearson’s correlation test between cognition (MMSE, ACE-III) and adherence (duration of OST taken).

Subjective Complain of Loss of Memory, Attention and Concentration and Thinking Ability

Subjective complaints of cognitive decline i.e., loss of memory, attention and concentration and thinking ability are corelated with scores of MMSE and ACE-III [Table/Fig-8].

Subjective complaints and scores of MMSE and ACE-III.

| Adherence | Subjective complaints | Scales |

|---|

| Memory loss | A and C loss | Loss of thinking ability | MMSE | ACE-III |

|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | <24 | >24 | <82 | >82 |

|---|

| Irregular | 1 | 11 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 2 | 11 | 1 |

| Regular | 4 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Very regular | 0 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 5 | 17 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 14 | 8 | 16 | 6 |

A and C: Attention and concentration; ACE-III: Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination-III; MMSE: Mini mental state examination

Interpersonal Complication

We studied opioid dependents conflict and violence with parents and sibling, spouse, children and friend. Though, results were not statistically significant, patients with history of interpersonal conflict and violent behaviour with family members had low cognitive scores and poor adherence. Patients who had marital disharmony and history of violence towards spouse had lower cognitive score and were irregular with respect to adherence which is significant on chi-square test (p=0.004 in ACE-III and p=0.005 in MMSE scale for violence towards spouse) [Table/Fig-9,10].

Association between cognition and interpersonal relationship.

| Interpersonal complication | ACE-III | Fisher’s-exact test | p-value | MMSE | Fisher’s-exact test | p-value |

|---|

| <82 | >82 | <24 | >24 |

|---|

| Parents and sibling | Conflict and family tension | No | 3 | 1 | 1.460 | 0.885 | 3 | 1 | 2.075 | 0.686 |

| Yes | 13 | 5 | 11 | 7 |

| Violence | No | 5 | 2 | 2.047 | 0.624 | 6 | 1 | 4.495 | 0.207 |

| Yes | 11 | 4 | 8 | 7 |

| Spouse | Marital disharmony | No | 6 | 2 | 2.024 | 0.727 | 6 | 2 | 3.450 | 0.38 |

| Yes | 10 | 4 | 8 | 6 |

| Violence | No | 2 | 5 | 11.019 | 0.004 | 1 | 6 | 10.961 | 0.005 |

| Yes | 14 | 1 | 13 | 2 |

| Children | Violence | No | 11 | 2 | 4.536 | 0.249 | 10 | 3 | 5.407 | 0.061 |

| Yes | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Friend | Conflict | No | 1 | 0 | 3.192 | 0.585 | 1 | 0 | 1.439 | 1.000 |

| Yes | 15 | 6 | 13 | 8 |

| Total | | | 16 | 6 | | | 14 | 8 | | |

ACE-III: Addenbrooke’s cognitive examination-III; MMSE: Mini mental state examination;

Association between adherence and interpersonal relationship.

| Interpersonal complication | Adherence | Fisher’s-exact test | p-value |

|---|

| IR | R | VR |

|---|

| Parents and sibling | Conflict and family tension | No | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4.977 | 0.548 |

| Yes | 9 | 5 | 4 |

| Violence | No | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5.365 | 0.481 |

| Yes | 8 | 4 | 3 |

| Spouse | Marital disharmony | No | 6 | 2 | 0 | 5.862 | 0.471 |

| Yes | 6 | 4 | 4 |

| Violence | No | 2 | 3 | 2 | 8.932 | 0.105 |

| Yes | 10 | 3 | 2 |

| Children | Violence | No | 8 | 4 | 1 | 6.184 | 0.473 |

| Yes | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Friend | Conflict | No | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3.743 | 0.932 |

| Yes | 11 | 6 | 4 |

| Total | | | 12 | 6 | 4 | | |

IR-Irregular; R-Regular; VR-Very regular

Discussion

In past, a cross-sectional health survey in Greek municipality was carried out in 1,356 adults by Koukouli S et al., to investigate the relative importance of sociodemographic and physical health status factors for subjective functioning, as well as to assess the role of social support. The analysis of variance showed that, all three social support variables (marital status, living arrangements and size of household) were significantly associated with functioning (p<0.001) [16]. In the present study though, the results were statistically not significant, irregularity were more in unemployed, illiterate, unmarried and in those from lower SEC [Table/Fig-2].

Another study done by Ownby RL et al., suggested that 80-90% of patients with mild memory impairment had high levels of medication adherence, functioned at independent levels in activities of daily living and lived with a spouse or another caregiver, while 10-20% of patients with significant evidence of memory impairment were identified as having low levels of adherence, typically living alone and reported that they relied on themselves [17].

As the alcohol and other psychoactive substances alone cause cognitive impairment, results were also consistent with this fact. A study was done by Henry PK et al., comparing cognitive performance in Methadone Maintenance Patients (MMPs) with and without current cocaine dependence which showed no significant differences in cognition between the two groups. Relative to MMP without cocaine dependence, MMP with cocaine use showed significant impairment on selective measures of psychomotor performance/attention (simple reaction time and trail making test A) and episodic memory. However, no study was done which correlates effects of cognition on OST adherence in substance dependent patients [18].

Another study by Gupta S et al explored the effects of intravenous heroin use and Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) on neuropsychological functioning in a sample of Chinese individuals receiving methadone maintenance treatment, by comparing them to demographically comparable HCV seronegative individuals who had no history of heroin use. Contrary to their expectations this study showed no evidence of neuropsychological impairment attributed to the combined risk factors like IDU, HCV infection, and methadone maintenance treatment [19].

A European study by Barat I et al., to assess medication adherence among old persons living in their own homes for assessing their knowledge of their medication and to indicate target areas for intervention showed that evidence of cognitive impairment (MMSE <24) increased the likelihood of non adherence nine times, and that elders living alone were twice as likely to had medication errors [20]. Many studies have been conducted to assess relation between cognition and adherence to treatment in patients with hypertension, HIV, diabetes etc., few studies were conducted comparing cognitive profile of patients on buprenorphine versus methadone as OST, However, no study was conducted for the effects of cognition on OST adherence treated with buprenorphine [21-23].

Many studies have been done to assess effect of interpersonal problems on drug adherence. One such study done by Delamater AM et al., assessing patient’s adherence for diabetes suggested that family relationships play an important role in diabetes management. Studies have shown that low levels of conflict, high levels of cohesion and organisation and good communication patterns were associated with better regimen adherence [24]. Greater levels of social support, particularly diabetes related support from spouses and other family members were associated with better regimen adherence [25]. Social support also serves to buffer the adverse effect of stress on diabetes management [26,27]. Therfore, interpersonal complication related to use of substance and psychosocial factors like social support, interpersonal relationship play a great role in adherence.

Conclusion

In the present study, IR patients were more unemployed, illiterate, unmarried and from lower SEC. Patients with opioid substance plus alcohol use and with other comorbid illness were found to have more cognitive decline and poor adherence to OST. Non adherent group patients who were irregular had statistically significant lower ACE-III score (p=0.032). Subjective complaints of cognitive decline were consistent with scores of MMSE and ACE-III.

Therefore, we conclude with the fact that cognition is the only robust factor which affect OST adherence and probably also responsible for no behavioural changes, continued harmful use and relapse in opioid dependent patients.

To improve adherence to OST it is necessary that patient should understand benefits of taking medication, maintain abstinence and take directly observed treatment which lead to new learning and behavioural change.