Introduction

One of the most common oral diseases worldwide is dental caries which remains a problem for the society and individuals. Dental caries is caused by an interplay of several factors like biological, behavioural, socioeconomic factors. Since, the 20th century, a significant decline in the prevalence of dental caries is observed primarily due to use of fluoridated toothpaste, but it still exists as a major pandemic disease affecting all age groups across the globe [1-3], with around 20-30% of adult population developing new caries lesion every year which requires operative treatment [4].

The prevention of dental caries in children and adolescents is generally contemplated as a priority for dental services and interpreted to be more cost-effective than its treatment. The important factor that brought the change in the caries picture worldwide in the last 25 years is the fluoride presence universally mainly in fluoridated water and fluoride toothpaste. Studies revealed that use of high fluoride toothpaste, especially 5000 ppm fluoride toothpaste significantly reduces the plaque accumulation, decreases the number of mutans streptococci and lactobacilli, increases the fluoride concentration in saliva and fluoride concentration in plaque and promotes the fluorapatite crystal formation which lessens the dental caries formation [5].

Description of the Disease Condition

Dental caries is an infectious, microbiological disease that results in localised dissolution of organic tissue and destruction of the calcified tissue of the teeth. Dental caries is affected by many factors which needs the existence of a liable host, caries prone microflora and diet which results in enamel demineralisation [6]. The bacterial acid production in the biofilm and the buffering action in saliva result in fluctuations in plaque pH. As the pH falls below a critical point, the demineralisation of enamel, dentine and cementum occurs and vice-versa [7]. Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus, play a major role in demineralisation. These bacteria are opportunistic pathogens, found commonly as members of the resident flora of persons without caries and expressing their pathogenicity, only under specific environmental conditions. Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus, two species of the ‘streptococci’ are the most significant in human caries, and studies of the microbial ecology of caries have been directed principally at these species. Since, late 1970s, specific plaque hypothesis states that mutans streptococci (MS) has been considered to be the main organism in producing dental caries [8]. According to a systematic review by Tanzer JM et al., mutans streptococci are responsible for caries initiation on enamel and root surfaces [9], though, mutans streptococci is not regarded as the only cause for the caries progression [10,11]. Ecological caries hypothesis reported that the presence of certain bacteria does not matter but the existence of bacteria with certain characteristic is responsible for dental caries [12]. Furthermore, Ten Cate JM et al., stated that “the arch criminals grow attached to surfaces embedded in a matrix to form a biofilm, and they are living in a complex bacterial society rather than isolated invaders in our oral ecosystem” [13]. It is therefore important to evaluate not only the type, increased consumption of fermentable carbohydrates are found to be linked with the initiation and establishment of caries [11,14].

Description of the Intervention

The history of fluoridation is more than 70-year-old. It started with the arrival of Dr. Fredrick MacKay in Colorado springs, Colorado, USA in 1901. The effect of fluoride in drinking water on dental health has been the subject of research and comment over 70 years. Studies show that the adjustment of fluoride concentration in drinking water to the optimum level of 1 ppm in temperate climate is associated with marked decrease in dental caries. The Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Heath Care in 2002 showed strong scientific evidence that the daily use of fluoridated toothpaste is an effective method for preventing dental caries in permanent teeth [3].

The rationale for using topical fluoride agents is to speed the rate and increase the concentration of fluoride acquisition above the level which occurs naturally. If individual’s, only exposure to fluoride (post-eruptive) is in drinking it may take years before surface enamel acquires an effective concentration.

Various studies report that the cariostatic effect of fluoride is mainly through the liquid phase surrounding the enamel. There are three principles of its mechanism of action: 1) inhibiting demineralisation; 2) Enhancing remineralisation; and 3) inhibiting bacterial metabolism [15].

Inhibiting Demineralisation

The strong affinity of fluoride for apatite is due to the highly sensitive nature of fluoride. The two example of this interface are the formation of Fluor-Hydroxyapatite (FHA) and calcium fluoride. At the low-level of fluoride concentration the FHA is mainly formed in a neutral environment, while at high fluoride concentration and at low pH level calcium fluoride is mainly formed [16]. An important effect on the solubility and dissolution of apatite is due to both the substances [17]. The calcium fluoride which is formed, behave as a slow release source at the tooth surface and this ability of acting as a reservoir is important clinically [13,16].

Enhancing Remineralisation

The remineralisation process in enamel and dentinal carious lesions is due to maintenance of low-level of fluoride in saliva and oral biofilm. These benefits of fluoride aids in being a testing parameter for caries inhibiting products [13,18].

Inhibiting Bacterial Metabolism

Bradshaw DJ et al., conducted a study on antimicrobial interactions of fluoride where they found that, the antimicrobial effects of fluoride on microbial communities is by dropping the overall acid production level (direct effect) and by decreasing the selection of acid tolerating species such as mutans streptococci’s (indirect effect) [19]. Thus, fluoride concentration in saliva and plaque reduces acid production by inhibiting metabolism of plaque bacteria [20].

Importance of this Review

The control of dental caries in children and adolescents is generally regarded as a prime concern for dental services and regarded to be more cost-effective than its treatment [21]. The introduction of water fluoridation schemes has come into existence over five decades, thus, maintaining the fluoride therapy to be the centerpiece of caries-preventive strategies [22].

Fluoride action on the tooth/plaque interface is the most important reason for the anticaries effect of fluoride as well as through promotion of remineralisation of early caries lesions and there by lessens the tooth enamel solubility [23]. The most common modalities used at present are fluoride-containing toothpastes (dentifrices), mouth rinses, gels and varnishes.

Toothpastes are by far the most extensive form of fluoride usage [22] and although the reasons for the decrease in the prevalence of dental caries in children, adolescent and adults from different countries continues to be a topic of debate [24]. The concentration of fluoride in the toothpaste is an important factor in caries prevention. The usual concentration of fluoride in toothpastes is 1000/1100 parts per million (ppm F); toothpastes with higher (1500 ppm F) and lower than conventional fluoride levels (around 500 ppm F) are also available in many countries.

In the European Union, the maximum concentration permissible in an Over-The-Counter (OTC) product is 1500 ppm. In Sweden, the most common concentration is 1450 ppm. There is an association between the concentration of fluoridated toothpaste and caries prevention due to which the affinity to increase the concentration of fluoride in dentifrices for adults and in children since last decade [15].

In various countries the introduction of high fluoride dentifrices with 5000 ppm fluoride has been done in patients with a high caries incidence. According to Cutress T et al., the use of 5000 ppm fluoride toothpaste significantly reduced caries more effectively as compared to the lower concentration fluoridated toothpaste [25]. According to Tavss EA et al., in a review, there seem to be an association between the reduction in caries incidence and the concentration of fluoride in dentifrices that is in between 0 and 5000 ppm, but there is an uncertainty in the dose-response curve at the high level of 5000 ppm [26].

The study is important and increasingly relevant to the delivery of preventive dentistry. Thus, this systematic review will be of help to the clinicians in knowing the effectiveness of 5000 ppm of fluoride dentrifice on dental caries.

The objective of the review was to determine whether 5000 ppm fluoridated toothpaste is more effective in preventing caries and to measure the effect of 5000 ppm flouride toothpaste on preventing caries and on caries related factors like dental plaque and salivary variables.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eligibility Criteria

The articles which were published in English, dated from the year 1960 to February 2016 were included in this review.

The search terms for articles were the terms either in the title or abstract. The articles which were taken for this study were full text original articles. Excluded articles including unpublished articles in press and personal communications, etc., were screened for the exclusion.

Original research articles, in vivo studies (randomised control trails), In vitro studies were included whereas Review articles, summary articles, letter to the editor, short communication were excluded for this review.

Search Method for Identification of Studies

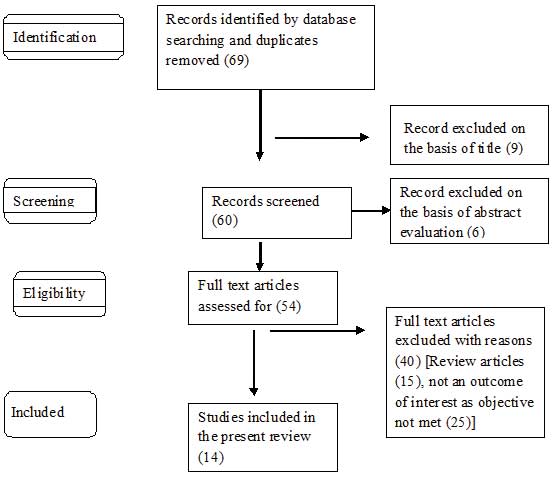

For the identification of the studies included in this review, we devised the search strategy for each database. The search strategy used a combination of controlled vocabulary and free text terms. The main database was PubMed (1960-2016), PubMed Central (1960-2016), Cochrane Review (1960-2016), Embase (1960-2016) and Google Scholar (1960-2016) [Table/Fig-1].

The search terms were 5000 ppm fluoride toothpaste, dental caries and 5000 ppm toothpaste for PubMed and PubMed central.

Other Sources

The search also included the hand search of the journals fulfilling the inclusion criterion for the review.

Results

The summary of the results has been provided in [Table/Fig-2a,b]. [27-40].

Summary of result (in vivo).

| Study | Title | Sample size | Patient characteristic | Duration of treatment | Study design | Dose | Blinding | Result/Summary |

|---|

| Baysan A et al., [27]. | Reversal of primary root caries using dentifrices containing 5000 and 1100 ppm fluoride. | 201 | Total 201 subject, 114 male, 87 female; all >18 year of age, had at least 10 teeth and one or more PRCLs (primary root caries lesion). | six months | Two groups Positive control dentifrice (1100 ppm) and test dentifrice (5000 ppm). | Toothpaste containing 1100 ppm and 5000 ppm F were used. | Double | Study demonstrated that Previdant 5000 PLUS (5000 ppm) is more effective in remineralisation of arrested root caries than Winterfresh gel (1100 ppm). |

| Ekstrand K et al., [28]. | Development and evaluation of two root caries controlling program for home based trail people older than 75 years. | 215 | Total 215 person agreed, 140 females mean age 81.6 years (ISD=4.3) 60% had one or two partial dentures. | eight months | Randomly assigned to three groupGroup 1: once a month dental hygienist brushed the teeth of participants and applied duraphat varnish to active caries lesionGroup 2 and 3: received 5000 ppm and 1450 ppm F toothpaste respectively to use twice daily. | 1450 ppm and 5000 ppm F toothpaste used. | Single | Root caries status in Group 1 and 2 improved significantly when compared with Group 3 (p<0.02). |

| Nordstrom A and Birkhed D [29]. | Effect of a third application of toothpaste (1450 and 5000) ppm F, including massage on F retention and pH drop in plaque. | 16 | Total 16 volunteers (age 23-38 year) mean age 26, with good general health and minimum 24 teeth. | two weeks | (1) 5000 ppm F; twice a day, (2) 5000 ppm; three times/day, (3) 5000 ppm; twice a day, plus the ‘massage’ method once a day, (4) 1450 ppm F; twice a day, (5) 1450 ppm; three-times/day and, (6) 1450 ppm; twice a day, plus the ‘massage’ method once a day. | 1450 and 5000 ppm F toothpaste were used. | Single | The highest mean peak salivary F concentrations were found in subjects using toothpaste with 5000 ppm fluoride and differed significantly from those with 1450 ppm. Brushing with high fluoride toothpaste three-times a day resulted in 3.6-times higher F concentration in saliva compared to standard paste twice a day. The F retention in plaque increased significantly as well. |

| Mannaa A et al., [30]. | Caries-risk profile variations after short-term use of 5000 ppm fluoride toothpaste. | 34 | Total 34 participants, 17 mother and their teenage children. | six weeks | Four visits:Baselinetwo weekfour weeksix week | One tube of 113 gm of high fluoridated toothpaste and a toothbrush with a coloured mark 2 cm from the bristle surface were used. | Not clear | Use of 5000 ppm F toothpaste resulted in a statistically significant modification of the caries-risk profile, increasing the actual chance of avoiding caries in the future among the mothers and teenagers at each visit following baseline (p<0.01). |

| Nordstrom A et al., [31]. | Effect on de novo plaque formation of rinsing with toothpaste slurries and water solutions with a high fluoride concentration (5000 ppm). | 16 | Sixteen healthy dental students, 21–43 year of age (mean age 27 years). | four days | Three groups:1) 5000 ppm2) 1500 ppm3) 500 ppm | 5000 ppm1500 ppm500 ppm | Single | Significantly less plaque was scored for dentifrice slurry containing 5000 ppm F (p<0.05). |

| Mannaa A et al., [32]. | Effect of high fluoride dentifrices (5000 ppm) on caries related plaque and salivary variables. | 34 | 17 families with total 34 participants, 17 mothers (38.4±6.4) and their 17 teenage children (14.5±1.2). | six weeks | Four visits:First visit (baseline).Second visit (two week).Third visit (four week).Fourth visit (six week). | One tube of 113 gm high fluoridated toothpaste contains 5000 ppm F of 1.1% NaF. | Not clear | Six week use of 5000 ppm fluoridated toothpaste significantly increased the salivary buffer capacity and a significant reduction in mutans streptococcus was observed (p<0.05). |

| Srinivasan M et al., [33]. | High fluoride toothpaste: multicenter randomised controlled trail in adults. | 130 | 130 adult patients:Male 74Female 56With mean age 56.9±12.9 diagnosed with root caries. | six months | Two groups:1) test group (5000 ppm).2) control group (1350 ppm). | Toothpaste with 5000 ppm and 1350 ppm F are used. | Single | Use of 5000 ppm F toothpaste twice daily significantly improves the surface hardness of otherwise untreated root caries when compared with 1350 ppm, thus reducing the root caries susceptibility in elderly adults. |

| Ekstrand KR et al., [34]. | A randomised clinical trial of anti-caries efficacy of 5000 ppm F compared to 1450 ppm F toothpaste on root caries lesion in elderly disabled nursing home resident. | 176 | 176 participants from six nursing home out of which 125 complete the study. | eight months | Two group:1) 5000 ppm2) 1450 ppm | 5000 ppm and 1450 ppm toothpaste are used. | Double | 5000 ppm toothpaste is more effective than 1450 ppm.Mean number of active root caries lesion to the follow up for 5000 ppm were 1.05 (2.67) vs 2.55 (1.9) for 1450 ppm.Mean number of arrested caries lesion for 5000 ppm was 2.3 (1.6) vs 0.61 (1.76) for 1450 ppm F toothpaste respectively. |

| Nordstrom A and Birkhed D [35]. | Preventive effect of high fluoride dentifrice (5000 ppm) in caries active adolescent: a two year clinical trial. | 279 | 279 healthy volunteers aged 14-16years of age: boys 146, girls 133 with caries activities with DMFS score ≥5 | Two years | Two groups:1) Test group (5000 ppm).2) Control group (1450 ppm). | Toothpaste with 5000 ppm F and 1450 ppm F to be used in 1 gm of quantity. | Single | Caries incidence and progression rate is comparatively low in 5000 ppm case. |

Summary of result (in vitro).

| Author/Year | Aim/Objective | Design | Result |

|---|

| Karlinsey RL et al., 2010 [36]. | Remineralisation potential of 5000 ppm F dentifrices evaluated in pH cycling model. | Three group:1) Tom of maine F free toothpaste.2) Colgate prevident booster 5000 ppm.3) 3M clinpro 5000 ppm (5000 ppm F plus 800 ppm functioning tri-calcium phosphate. | Clinpro 5000 conferring superior surface and subsurface remineralisation potential relative to both prevident booster 5000 and tom of maine F free toothpaste (p<0.05). |

| Pulido MT et al., 2008 [37]. | The inhibitory effect of MI paste, fluoride and a combination of both on the progression of artificial caries like lesion in enamel. | Five groups:1) artificial saliva2) NaF 5000 ppm3) MI paste4) NaF 1100 ppm5) NaF 1100 ppm plus MI paste | No significant difference was found between the artificial saliva, MI paste, NaF 1100 ppm and combination of NaF 1100 ppm plus MI paste but the higher concentration of NaF 5000 ppm reduced lesion to greatest extent (p<0.05). |

| Diamanti I et al., 2011 [38]. | To assess the effect of toothpaste containing three different NaF concentration and a calcium sodium phosphor-silicate system, on root dentin demineralisation and remineralisation. | Five group:1) non-fluoridated2) 7.5% calcium sodium phosphor-silicate3) 1450 ppm F4) 2800 ppm F5) 5000 ppm F | 5000 ppm F toothpaste group during pH cycling presented significantly less total vol% mineral loss and subsequently exhibited considerably increase surface acid resistance, compared to all other tested group. |

| Bizhang M et al., 2009 [39]. | Effect of a 5000 ppm F toothpaste and a 250 ppm F mouth rinse on the demineralisation of dentin surface. | Three group:1) 5000 ppm F toothpaste2) 250 ppm F mouth rinse3) distilled water | The result suggest that treatment of demineralised dentin with a toothpaste containing 5000 ppm F may considerably reduce mineral loss and lesion depth in exposed dentin. |

| Basappa N et al., 2013 [40]. | To investigate and compare the efficacy of two products, tooth mousse and clinpro tooth crème on remineralisation and tubule occluding ability with 5000 ppm F containing toothpaste. | Three group1) 5000 ppm NaF2) GC MI paste3) Clinpro toothpaste | NaF 5000 ppm have found to be relatively superior in remineralising and desensitising agent when compared to other tested group (p<0.01). |

The included results were evaluated for the study design, blinding and evaluation period [Table/Fig-3] [27-35].

Study design, Blinding, Evaluation period.

| Randomised clinical trial | Parallel design | Cross over Design | Single blind | Double blind | Triple blind | No mention of blinding | Baseline evaluation |

|---|

| Baysan A et al., [27]. | √ | - | √ | - | - | - | √ |

| Ekstrand K R et al., [28]. | √ | - | √ | - | - | - | √ |

| Nordstrom A and Birkhed D, [29]. | - | √ | - | √ | - | - | - |

| Mannaa A et al., [30]. | √ | - | - | - | - | √ | √ |

| Nordstrom A et al., [31]. | - | √ | √ | - | - | - | - |

| Mannaa A et al., [32]. | √ | - | - | - | - | √ | √ |

| Srinivasan M et al., [33]. | √ | - | √ | - | - | | √ |

| Ekstrand K R et al., [34]. | √ | - | - | √ | - | - | √ |

| Nordstrom A and Birkhead D [35]. | √ | - | √ | - | - | | √ |

Study Outcomes

Differences between baseline and end-of-trial scores for parameters of interest are shown in [Table/Fig-4] [28,30,32-35].

Difference between baseline evaluation and post intervention evaluation (results from previous studies).

| Study | Index | Intervention/Group | Baseline Evluation | Post-Intervention Evaluation | p-value |

|---|

| Ekstrand K et al., [28] | | 1) Group 1-Duraphat Varnish2) Group 2-5000 ppm F toothpaste3) Group 3-1450 ppm F toothpaste | Active lesion:Group 1-81Group 2-82Group 3-77Arrested lesion:Group 1-56Group 2-51Group 3-48 | Active lesion:Group 1-31Group 2-57Group 3-98Arrested lesion:Group 1-57Group 2-73Group 3-46 | p<0.02 |

| Mannaa A et al., [30]. | | 5000 ppm F toothpaste | Chance of avoiding caries–29.5±3.6 | Chance of avoiding caries:two week-43.8±3.8four week-48.7±4.3six week-54.7±2.6 | p<0.01 |

| Mannaa A et al., [32]. | | 5000 ppm F toothpaste | 0.45±0.04 | 0.55±0.06 | p<0.05 |

| Srinivasan M et al., [33]. | | 1) Test Group (5000 ppm)2) Control Group (1450 pmm) | Hardness Score1) Test Group-3.4±0.612) Control Group-3.4±0.66 | Hardness Score1) Test Group-2.4±0.812) Control Group-2.8±0.79 | p<0.001 |

| Ekstrand KR et al., [34]. | | 1) Intervention Group-5000 ppm2) Control Group-1450 ppm | Active Lesion1) Intervention Group-1602) Control Group-166Arrested Lesion1) Intervention Group-342) Control Group-35 | Active Lesion1) Intervention Group-632) Control Group-161Arrested Lesion1) Intervention Group-1312) Control Group-41 | p<0.001 |

| Nordstrom A and Birkhead D [35]. | DFS | 1) 5000 ppm2) 1450 ppm | 1) 1.58±1.652) 1.41±1.35 | 1) 1.03±1.162) 1.34±1.55 | p<0.05 |

Risk of Bias in Included Studies

Based on seven studies, the three studies conducted were at high risk for incomplete outcome data, three studies conducted were at high risk for random sequence generation, the two studies conducted were at low-risk for allocation concealment, five studies conducted were at high-risk for blinding of outcome assessment and the six studies were at low-risk for selective outcome reporting [Table/Fig-5a,b].

| Reference | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data addressed | Selective outcome reporting |

|---|

| Baysan A et al., [27]. | High-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Unclear | Low-risk |

| Ekstrand K et al., [28]. | Unclear | Unclear | High-risk | High-risk | Low-risk |

| Nordstrom A and Birkhead D [29]. | Unclear | Unclear | High-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk |

| Nordstrom A et al., [31]. | Unclear | Unclear | High-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk |

| Srinivasan M et al., [33]. | High-risk | Low-risk | High-risk | High-risk | Low-risk |

| Ekstrand KR et al., [34]. | Unclear | Unclear | Low-risk | Unclear | Unclear |

| Nordstrom A and Birkhed D [35]. | High-risk | Unclear | High-risk | High-risk | Low-risk |

| Criteria | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data addressed | Selective outcome reporting |

|---|

| Low-risk | Referring to a random number table;Using computer random number generator. | Participants and investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment because one of the following, or an equivalent method, was used to conceal allocation:central allocation (including telephone, web-based and pharmacy-controlled randomisation);sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance;sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. | Blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. | No missing outcome data;reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias);missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups. | The study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre-specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre-specified way;the study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre-specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon). |

| High-risk | Allocation by judgement of the clinician;allocation by preference of the participant. | Using an open random allocation schedule (e.g., a list of random numbers);assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g., if envelopes were unsealed or non-opaque or not sequentially numbered);alternation or rotation;date of birth;case record number;any other explicitly unconcealed procedure. | No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding;blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups. | Not all of the study’s pre-specified primary outcomes have been reported;one or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g., subscales) that were not pre-specified;one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre-specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect). |

| Unclear | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement of ‘low-risk’ or ‘high-risk’. | | | | |

Discussion

The goals addressed by this review are the effectiveness of fluoride toothpaste for dental caries prevention in children, adolescents, young adults and elders compared to other traditional F toothpaste.

Studies reveals that high fluoride dentifrices has a more protective action on caries in children, adolescents and young adults than traditional toothpaste with 500, 800,1050–1450 ppm F [2,41]. The aim of this review was to search for the evidence pertaining to high fluoride toothpaste and to assess whether it has a greater potential to prevent caries in the children, adolescents, young adults and elderly/vulnerable section of the society than traditional toothpaste with 500, 800, 1050–1450 ppm flouride.

The 5000 ppm flouride toothpaste showed significant reduction in the caries incidence rate and a significant increase in the buffer capacity when compared to other traditional low flouride containing toothpaste. The findings are in agreement with the study conducted by Mannaa A et al., and Nordstrom A and Birkhed D, where they suggested that the caries progression and incidence rate reduced in subjects using 5000 ppm flouride toothpaste and also there was significant reduction in S.mutans count [32,35].

It was noted that the 5000 ppm flouride toothpaste is more effective when compared to 1350 ppm and 1450 ppm in reducing root caries and thus, reducing the root caries incidence and improving surface hardness of untreated root caries. The findings were seen to be in agreement with the studies conducted by Srinivasan M et al., Ekstrand KR et al., where they suggested that 5000 ppm F toothpaste had better results in reducing the root caries susceptibility in adults as compared with 1350 ppm and 1450 ppm flouride toothpaste respectively [33,28,34].

Study conducted by Nordstrom A and Birkhead D suggested that the use of 5000 ppm flouride toothpaste helps in increasing the salivary flouride concentration and increased flouride retention in plaque when compared with 1450 ppm flouride toothpaste [29]. It was seen that the use of 5000 ppm flouride toothpaste significantly reduces the chance of avoiding caries and results in modification of caries risk profile, which are in agreement to a study conducted by Manna A et al., [30].

The use of 5000 ppm flouride toothpaste was proved to have better results in surface and subsurface remineralisation potential when compared with other traditional flouride toothpaste. The findings are in agreement with the study conducted by Karlinsey RL et al., which suggested that 5000 ppm F toothpaste had better remineralisation potential [36]. Study conducted by Bizhang M et al., and Basappa N et al., suggested that 5000 ppm flouride toothpaste had superior remineralisation and significantly decreased the demineralisation or mineral loss on extracted tooth and even on artificially caries like lesion in enamel [39,40].

Thus, from this present review it is inferred that the use of dentifrices with 5000 ppm of flouride would significantly improve remineralisation, salivary concentration of fluoride, modifies caries risk, reduces root caries susceptibility and prevent mineral loss. There are number of potential fluoride sources such as fluoridated water, fluoride tablets, gels or varnishes, the total intake must be estimated before using 5000 ppm fluoridated toothpaste.

Also, though no data is available on humans but studies in animals have shown reproductive toxicity of sodium fluoride when administered at very high-level [42].

Recommendations

Children within the age group of 12 years are more suitable for the usage of high concentration fluoride toothpaste as it will be more helpful for the protection of the newly erupted premolars and second molars and there is also no risk of fluorosis beyond this age.

Adults and teenagers with a high caries risk constitute a suitable target group for using a dentifrice with 5000 ppm flouride.

A high fluoride dentifrice can be recommended for optimal caries prevention strategies during orthodontic treatment.

Conclusion

Studies revealed that the use of 5000 ppm flouride toothpaste significantly improves the remineralisation, salivary concentration of fluoride, fluoride retention in plaque, modifies caries risk, reduces root caries susceptibility and prevent mineral loss. Thus, 5000 ppm flouride dentifrices have better caries prevention potential and superior effects on caries related factors like dental plaque and salivary variables and these dentifrices must be used after consultation with a dentist.

[1]. Bratthall D, Petersson HG, Sundberg H, Reasons for the caries decline: what do the experts believe?Eur J Oral Sci 1996 104(4):416-22.10.1111/j.1600-0722.1996.tb00104.x8930592 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2]. Marinho VC, Higgins JP, Logan S, Sheiham A, Fluoride varnishes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescentsCochrane Database Syst Rev 2002 (3):CD00227910.1002/14651858.CD002279PMC136440 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[3]. Twetman S, Axelsson S, Dahlgren H, Holm AK, Källestål C, Lagerlof F, Caries-preventive effect of fluoride toothpaste: A systematic reviewActa Odontol. Scand 2003 61(6):347-55.10.1080/0001635031000759014960006 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[4]. Zickert I, Jonson Å, Klock B, Krasse B, Disease activity and need for dental care in a capitation plan based on risk assessmentBr Dent J 2000 189(9):48010.1038/sj.bdj.480080511104101 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[5]. Ekstrand KR, Ekstrand ML, Lykkeaa J, Bardow A, Twetman S, Whole-saliva fluoride levels and saturation indices in 65+ elderly during use of four different toothpaste regimensCaries Res 2015 49(5):489-98.10.1159/00043473026278523 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[6]. Keyes PH, Jordan HV, Factors influencing the initiation, transmission and inhibition of dental caries. Mechanisms of hard tissue destruction. Sognnaes RF, editor 1963 New York, NYAmerican Association for the Advancement of Science:261-83. [Google Scholar]

[7]. Kidd EA, Fejerskov O, What constitutes dental caries? Histopathology of carious enamel and dentin related to the action of cariogenic biofilmsJ Dent Res 2004 83(1_suppl):35-38.10.1177/154405910408301s0715286119 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[8]. Loesche WJ, Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decayMicrobiol Rev 1986 50:353-80. [Google Scholar]

[9]. Tanzer JM, Livingstone J, Thompson AM, The microbiology of primary dental caries in humansJ Dent Educ 2001 65:1028-37. [Google Scholar]

[10]. Bowden GH, Does assessment of microbial composition of plaque/saliva allow for diagnosis of disease activity of individuals?Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1997 25(1):76-81.10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00902.x9088695 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[11]. Takahashi N, Nyvad B, The role of bacteria in the caries process: ecological perspectivesJ Dent Res 2011 90:294-303.10.1177/002203451037960220924061 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[12]. Marsh PD, Devine DA, How is the development of dental biofilms influenced by the host?J Clin Periodontol 2011 38(s11):28-35.10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01673.x21323701 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[13]. Ten Cate JM, Exterkate RA, Buijs MJ, The relative efficacy of fluoride toothpastes assessed with pH cyclingCaries Res 2006b 40:136-41.10.1159/00009106016508271 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[14]. Newbrun E, Sucrose, the arch criminal of dental cariesOdontol Revy 1967 18:373-86. [Google Scholar]

[15]. Nordstrom A, High-fluoride toothpaste (5000 ppm) in caries prevention 2011 Available at: https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/24499/1/gupea_2077_24499_1.pdf [Google Scholar]

[16]. Rølla G, Saxegaard E, Critical evaluation of the composition and use of topical fluoride with emphasis on the role of calcium fluoride in caries inhibitionJ Dent Res 1990 69:780-85.10.1177/00220345900690S1502179341 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[17]. Shellis RP, Duckworth RM, Studies on the cariostatic mechanisms of fluorideInt Dent J 1994 44:263-73. [Google Scholar]

[18]. Lynch RJ, Navada R, Walia R, Low levels of fluoride in plaque and saliva and their effects on demineralisation and remineralisation of enamel; role of fluoride toothpastesInt Dent J 2004 54:304-09.10.1111/j.1875-595X.2004.tb00003.x15509081 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[19]. Bradshaw DJ, Marsh PD, Hodgson RJ, Visser JM, Effect of glucose and fluoride on competition and metabolism within in vitro dental bacterial communities and biofilmsCaries Res 2002 36:81-86.10.1159/00005786412037363 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[20]. Marquis RE, Antimicrobial actions of fluoride for oral bacteriaCan J Microbio 1995 41:955-64.10.1139/m95-1337497353 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[21]. Burt BA, Pai S, Sugar consumption and caries risk: a systematic reviewJ Dent Educ 2001 65:1017-23. [Google Scholar]

[22]. Marinho VC, Higgins JP, Logan S, Sheiham A, Fluoride varnishes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescentsCochrane Database Syst Rev 2002 :310.1002/14651858.CD002279PMC136440 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[23]. Featherstone JD, Prevention and reversal of dental caries: role of low level fluorideCommunity Dent Oral Epidemiol 1999 27:31-40.10.1111/j.1600-0528.1999.tb01989.x10086924 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[24]. Nadanovsky P, Sheiham A, Relative contribution of dental services to the changes in caries levels of 12-year-old children in 18 industrialized countries in the 1970s and early 1980sCommunity Dent Oral Epidemiol 1995 23:331-39.10.1111/j.1600-0528.1995.tb00258.x8681514 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[25]. Cutress T, Howell PT, Finidori C, Abdullah F, Caries preventive effect of high fluoride and xylitol containing dentifricesJ Dent Child 1992 59:313-18. [Google Scholar]

[26]. Tavss EA, Mellberg JR, Joziak M, Gambogi RJ, Fischer SW, Relationship between dentifrice fluoride concentration and clinical caries reductionAm J Dent 2003 16:369-74. [Google Scholar]

[27]. Baysan A, Lynch E, Ellwood R, Davies R, Petersson L, Borsboom P, Reversal of primary root caries using dentifrices containing 5000 and 1100 ppm fluorideCaries Res 2001 35:41-46.10.1159/00004742911125195 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[28]. Ekstrand K, Martignon S, Holm-Pedersen P, Development and evaluation of two root caries controlling programmes for home-based frail people older than 75 yearsGerodontology 2008 25:67-75.10.1111/j.1741-2358.2007.00200.x18194330 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[29]. Nordstrom A, Birkhed D, Effect of a third application of toothpastes (1450 and 5000 ppm F) including a ‘massage’ method on fluoride retention and pH drop in plaqueActa Odontol Scand 2013 71:50-56.10.3109/00016357.2011.65423822320714 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[30]. Mannaa A, Campus G, Carlen A, Lingstrom P, Caries-risk profile variations after short-termuse of 5000 ppm fluoride toothpasteActa Odontol Scand 2014(a) 72:228-34.10.3109/00016357.2013.82255024175662 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[31]. Nordstrom A, Mystikos C, Ramberg P, Birkhed D, Effect on de novo plaque formation of rinsing with toothpaste slurries and water solutions with a high fluoride concentration (5000 ppm)Eur J Oral Sci 2009 117:563-67.10.1111/j.1600-0722.2009.00674.x19758253 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[32]. Mannaa A, Carlen A, Zaura E, Buijs MJ, Bukhary S, Lingstrom P, Effects of high-fluoride dentifrice (5000 ppm) on caries-related plaque and salivary variablesClin Oral Investig 2014b 18:1419-26.10.1007/s00784-013-1119-824100637 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[33]. Srinivasan M, Schimmel M, Riesen M, Ilgner A, Wicht MJ, Warncke M, High-fluoride toothpaste: a multicenter randomized controlledtrial in adultsCommunity Dent Oral Epidemiol 2014 42:333-40.10.1111/cdoe.1209024354454 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[34]. Ekstrand KR, Poulsen JE, Hede B, Twetman S, Qvist V, Ellwood RP, A randomized clinicaltrial of the anti-caries efficacy of 5000 compared to 1450 ppm fluoridated toothpaste on root caries lesions in elderly disabled nursing home residentsCaries Res 2013 47:391-98.10.1159/00034858123594784 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[35]. Nordstrom A, Birkhed D, Preventive effect of high-fluoride dentifrice (5000 ppm) in caries-active adolescents: A 2-year clinical trialCaries Res 2010 44:323-31.10.1159/00031749020606431 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[36]. Karlinsey RL, Mackey AC, Walker ER, Amaechi BT, Karthikeyan R, Najibfard K, Remineralization potential of 5000 ppm fluoride dentifrices evaluated in a pH cycling modelJ Dent Oral Hyg 2010 2(1):01-06. [Google Scholar]

[37]. Pulido MT, Wefel JS, Hernandez MM, Denehy GE, Guzman-Armstrong S, Chalmers JM, The inhibitory effect of MI paste, fluoride and a combination of both on progression of artificial caries-like lesions in enamelOper Dent 2008 33:550-55.10.2341/07-13618833861 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[38]. Diamanti I, Koletsi-Kounari H, Mamai-Homata E, Vougiouklakis G, In vitro evaluation of fluoride and calcium sodium phosphosilicate toothpastes, on root dentine caries lesionsInt J Dent Oral Health 2011 39(9):619-28.10.1016/j.jdent.2011.06.00921756964 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[39]. Bizhang M, Chun YH, Winterfeld MT, Altenburger MJ, Raab WH, Zimmer S, Effect of a 5000 ppm fluoride toothpaste and a 250 ppm fluoride mouth rinse on the demineralisation of dentin surfacesBMC Res Notes 2009 2:14710.1186/1756-0500-2-14719627581 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[40]. Basappa N, Jaiswal A, Kumar M, Prabhakar AR, In vitro re-mineralization of enamel subsurface lesions and assessment of dentine tubule occlusion from NaF dentifrices with and without calciumJ Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 2013 31:29-35.10.4103/0970-4388.11240323727740 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[41]. Davies RM, Davies GM, High fluoride toothpastes: their potential role in a caries prevention programDent Update 2008 35:320-23.10.12968/denu.2008.35.5.32018605525 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[42]. Al-Hiyasat AS, Elbetieha AM, Irbid HD, Jordan Reproductive toxic effects of ingestion of sodium fluoride in female ratsFluoride 2000 33:79-84. [Google Scholar]