Case Report

A 22-year-old male patient reported to the Department of Periodontology with the chief complaint of receded gums in lower front teeth region from past one year. Past medical history revealed no history of any systemic diseases, drug allergy or history of hospitalisation. Patient was a non-smoker and did not have any contraindications for periodontal surgery. Dental history revealed that the patient had ineffective oral hygiene maintenance due to limitations in tooth brush placement resulting in plaque accumulation. The patient had a complete periodontal examination which included the measurement of Probing Depth (PD) (distance between the most apical point of the gingival margin and the bottom of the pocket), Clinical Attachment Level (CAL) {distance between Cementoenamel Junction (CEJ) and bottom of the pocket), Keratinised Tissue (KT) (distance between the most apical point of the gingival margin and mucogingival junction}, and Vertical Recession (VR) (distance between CEJ and the most apical point of gingival margin) were measured with a graded periodontal probe (PCP UNC-15, Hu friedy, Chicago, IL) to the nearest millimeter from the recession sites.

The salient findings noted were the presence of generalised gingival inflammation with marginal tissue recession in 31, 41 associated with aberrant frenulum and a decreased width of attached gingiva. Spacing and mild proclination was noted in the lower anteriors. Intra oral periapical radiograph of region 31, 32, 41 and 42 revealed interdental horizontal bone loss extending till the junction of coronal and middle one-third of the root surface. Based on the clinical and radiographic findings, a diagnosis of plaque induced gingivitis with localised chronic periodontitis in relation to 31, 32, 41 and 42 was given. As there was presence of alveolar bone loss along with malocclusion, diagnosis of Miller’s Class III gingival recession in relation 31 and 41 was given [Table/Fig-1].

Clinical and radiographic picture showing Miller’s class III gingival recession.

The treatment plan was explained and a written informed consent was obtained from the patient before treatment.

Surgical Procedure

Initial phase I therapy consisting of scaling, root surface debridement and occlusal correction was done. The patient was recalled six weeks after the maintenance phase. The baseline and re-evaluation scores are shown in [Table/Fig-2].

The tabular column shows the baseline and re-evaluation data for tooth number 31, 41.

| Parameters tooth no: 31 (In mm) | After phase I therapy | 12 Months | Gain | Paramters tooth no: 41 (In mm) | After phase I Therapy | 12 Months | Gain |

|---|

| PD | 2 | 1 | 1 | PD | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| CAL | 5 | 0 | 5 | CAL | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| VR | 4 | 0 | 4 | VR | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| KTW | 2 | 3 | 5 | KTW | 1 | 3 | 4 |

PD: Probing depth, CAL: Clinical attachment level, VR: Vertical recession, KTW: Keratinised tissue width

Following re-evaluation phase, periodontal plastic surgical procedure consisting of frenectomy accompanied by a gingival unit transfer to eliminate the recession and provide adequate zone of attached gingiva was planned in 31, 41.

The surgical procedure was done under lignocaine with 1:80,000 adrenaline. Supra periosteal infiltration was given in 31, 41 region. The recipient site was prepared by giving two beveled vertical incisions distal to 31 and 41, removing the surfaces of interdental papillae and extending apically mesial to the convexities of adjacent teeth, 3 to 4 mm beyond the mucogingival line [1]. The outline of the recipient site was trapezoidal as the incisions were oblique and divergent. The vertical incisions were joined at their bases by horizontal incisions that perforated the periosteum and the substance of the labial frenum. The soft tissue within these limits were removed by sharp dissection, completing a frenectomy and the base of the recipient site was about ≥5 mm apical to the most apical part of the recession. The exposed portion of the root surface was prepared with a curette and then rinsed with sterile saline thoroughly [Table/Fig-3].

Recipient site prepared in relation to 31 and 41.

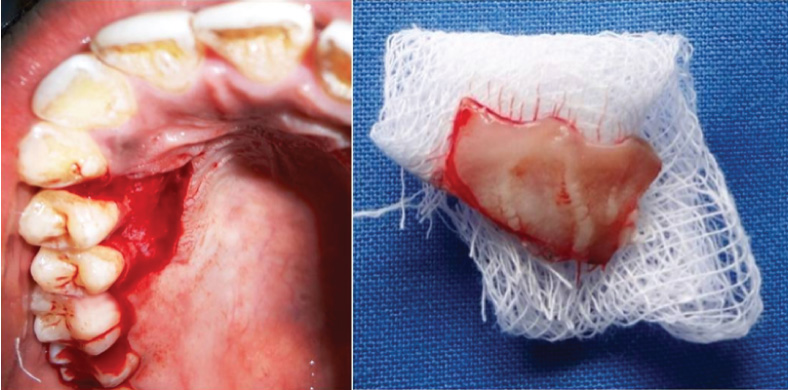

Following a greater palatine nerve block, the donor gingival unit graft was harvested from the palatal aspect of maxillary first and second premolar using a 15 size BP blade. The graft was harvested by including the gingival margin along with the interdental papilla with a thickness of about 1 to 1.5 mm. The graft was separated along the outline using a small tissue holding pliers and the overhanging tissues were trimmed from the undersurface of the graft [Table/Fig-4].

The gingival unit transfer graft harvested from the palatal region of 14 and 15. (Images from left to right)

The graft was then contoured, adapted, sutured with simple interrupted sutures in a position at the level slightly coronal to the CEJ with 5-0 Vicryl sutures. Periosteal anchoring suture was placed at the apical portion of the graft to assure intimate contact between the graft and the recipient bed. The graft was compressed and held in position for two minutes to reduce the dead space [Table/Fig-5]. For post-surgical care, patient was prescribed analgesics and antibiotics for a period of five days. The patient was advised to rinse twice daily with 0.2% chlorhexidine solution for three weeks and to avoid brushing and hard chewing. Periodontal dressing and suture removal was done after 10 days [2].

The graft placed in the recipient site and sutured with resorbable sutures.

At one month post-operative period, clinical healing at both the recipient and donor site was complete and no complications were observed. A 100% root coverage was achieved in 31, 41 [Table/Fig-6]. The margins of the graft appeared slightly coronally positioned than the adjacent gingival margins. The colour match with the adjacent tissues was acceptable although, slight differences could be noted. Patient was recalled at an interval of three, six and 12 months. At each visit the baseline parameters were re-evaluated and recorded. At the end of 12 months, 4 mm defect coverage with a PD of 1 mm, CAL gain of 5 mm and KT gain of 5 mm was observed in relation to 31 and 3 mm defect coverage with a PD of 1 mm, CAL gain of 4 mm and KT gain of 4 mm was observed in relation to 41 [Table/Fig-1].

The post-operative picture after 12 months showing complete root coverage in 31 and 41 with acceptable aesthetics and colour match.

Discussion

Free Gingival Grafts (FGGs) were initially described by Bjorn H [3]. The term FGG was first suggested by Nabers JM [4]. Since then, it has been a common technique to cover denuded root surfaces, to increase the width and thickness of attached gingiva. The advantages of using an FGG are high predictability and relative ease of technique. However, the conventional FGG has certain inherent limitations such as aesthetic mismatch and bulky appearance [5]. Various modifications have been developed in the donor and recipient tissues in order to overcome the limitations of FGG.

Gingival unit graft is a variant of FGG in which the palatal graft is harvested along with the marginal gingiva and interdental papilla. This technique was first described by Allen AL and Cohen DW [1]. One of the key factors for success to root coverage procedures is the vascularity. The synergistic relation between vascular configuration and related tissues plays a vital role in the success of soft tissue grafts [2].

Gingiva has a unique structure and characteristics [6,7]. The marginal gingiva has rich horizontal anastamoses of capillaries which does not extend to the interproximal zone. Use of site specific donor tissue such as “gingival unit graft” may increase the survival rate of the graft at the recepient site, which lacks optimal blood perfusion [2].

There are several capillaries and small vessels which form loops and repetitive network which extend to the marginal gingiva and it has been showed that the predominant gingival vessels decrease in size and increase in number as they extend coronally [2]. Hence, the increased vascular configuration of the donor tissue can better match the recipient site and provide a favourable aesthetic outcome and tissue blend.

The effficacy of GUT graft was studied by Kuru B and Yildirim S where a RCT was done by comparing FGG and GUT in Miller’s class I and II defects. The authors concluded that GUT had better aesthetic outcome when compared with FGG and 50% of the sites in gingival unit group showed complete defect coverage at the end of eight months [2]. A recent RCT by Jenabian N et al., was a split mouth study design done comparing FGG with GUT in Miller’s class I and II recession. The GUT side produced significantly greater aesthetic satisfaction, higher healing index, low post-surgical pain score and greater reduction in recession width when compared with FGG [8].

Although, there are a few case reports and studies done on Miller’s class I and II defects, literature search currently revealed only one case report by Yildirim S and Kuru B for Miller’s class III defect, in which they had compared a case of FGG with GUT and concluded that gingival unit technique showed greater recession depth reduction and defect coverage when compared with FGG [9].

In the present case we achieved 100% defect coverage in 31 and 41 Miller’s class III recession however Yildirim S and Kuru B in their case report had achieved 83% defect coverage and 2.5 mm of reduction depth reduction [9]. At three month interval an acceptable colour and configuration harmony was noted in 31, 41 region. Although, GUT technique resulted in almost indistinguishable texture and colour with the neighbouring tissues [9], in the present case report there was some slight differences in the colour seen when compared with the adjacent tissues at 12 month interval. Healing was uneventful in palatal donor site with no attachment loss or recession evident after one year of follow up.

Although, there are a few case reports and studies done on Miller’s class I and II defects, literature search currently revealed only one case report by Yildirim S and Kuru B for Miller’s class III defect, in which they had compared a case of FGG with GUT and concluded that gingival unit technique showed greater recession depth reduction and defect coverage when compared with FGG [9].

Over the years, the FGG has lost its popularity and preference against subepithelial connective tissue grafts or coronally advanced flaps in the treatment of gingival recessions, however, it is still the key procedure for increasing the KT zone and a modification like GUT maximises the success of root coverage by rapid re-establishment of vascularity in such non- submerged grafts [10].

Conclusion

Thus, GUT can be a predictable surgical procedure for the management of Miller’s class III gingival recession. Although, this technique is easy and less invasive, factors such as proper plaque control, root surface biocompatability, careful surgical manipulation and tissue thickness have been proven to be critical which might affect the outcome of the grafting procedure. Further, clinical studies are needed to show the efficacy of this technique for treatment class III gingival recession.

[1]. Allen AL, Cohen DW, King and Pennel’s free graft series: a defining moment revisitedCompend Contin Educ Dent 2003 24(9):698-700.:702:704-06. [Google Scholar]

[2]. Kuru B, Yildirim S, Treatment of localized gingival recessions using gingival unit grafts: a randomized controlled clinical trialJ Periodontol 2013 84(1):41-50.10.1902/jop.2012.11068522390550 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[3]. Bjorn H, Free transplantation of gingiva propriaSver Tandlakarforb Tidn 1963 22:684 [Google Scholar]

[4]. Nabers JM, Free gingival graftsPeriodontics 1966 4(5):243-45. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Cohen ES, Atlas of Cosmetic and Reconstructive Periodontal Surgery 1994 2nd edPhiladelphiaWilliams and Wilkins:65-135. [Google Scholar]

[6]. Schroeder HE, Listgarten MA, The gingival tissues: the architecture of periodontal protectionPeriodontol 2000 1997 13(2):91-120.10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00097.x9567925 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[7]. Folke LE, Stallard RE, Periodontal microcirculation as revealed by plastic microspheresJ Periodontal Res 1967 2(1):53-63.10.1111/j.1600-0765.1967.tb01996.x4229974 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[8]. Jenabian N, Bahabadi MY, Bijani A, Rad MR, Gingival unit graft versus free gingival graft for treatment of gingival recession: a randomized controlled clinical trialJournal of Dentistry of Tehran University of Medical Sciences 2016 13(3):184-92. [Google Scholar]

[9]. Yildirim S, Kuru B, Gingival unit transfer using in the Miller III recession defect treatmentWorld J Clin Cases 2015 3(2):199-203.10.12998/wjcc.v3.i2.19925685769 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[10]. Langer B, Langer L, Subepithelial connective tissue graft technique for root coverageJ Periodontol 1985 56(12):715-20.10.1902/jop.1985.56.12.7153866056 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]