Pancreatitis is the inflammatory process in which pancreatic enzymes cause autodigestion of the gland. Acute pancreatitis is the sudden onset of reversible inflammation of pancreas; whereas, chronic pancreatitis has ongoing inflammation and destruction that may occur insidiously, and is a progressive disorder [1]. Acute pancreatitis varies from mild (mortality rate <1%; usually resolves in several days) to severe (mortality rate can be up to 30%). Mortality rates are highest with necrotising pancreatitis, hemorrhagic pancreatitis and multiorgan dysfunction or failure. In necrotising pancreatitis, infection increases the mortality rate substantially. The incidence of acute pancreatitis ranges from 5 to 80 per 100,000 population, with the highest incidence in the United States and Finland. In Luneburg, Germany, the incidence was found to be 17.5 cases per 100,000 people. In Finland, the incidence was observed to be 73.4 cases per 100,000 people [2].

Acute pancreatitis has an incidence of about 40 cases per year per 100,000 adults in United States [3]. The incidence of chronic pancreatitis is approximately 4 to 8 per 100,000 with an approximate prevalence of 26-42 cases per 100,000 [4]. In 2013 pancreatitis resulted in 123,000 deaths which is increased from 83,000 deaths reported in 1990 [5]. The median age at onset of pancreatitis depends on the etiology [Table/Fig-1] [6]. The overall mortality in acute pancreatitis is approximately 10%-15%. Biliary pancreatitis is associated with higher mortality in comparison with alcoholic pancreatitis. This mortality rate has been falling over the last two decades with improvements in medical care. In patients with organ failure, accounting approximately 20% of presentations in hospital, mortality is about 30% [7].

Pancreatic necrosis is a parenchymal nonviable area associated with peripancreatic fat necrosis and is diagnosed with spiral CT scans. Differentiating infected and sterile pancreatic necrosis is an ongoing clinical challenge. Sterile pancreatic necrosis responds to medical management; whereas, infected pancreatic necrosis requires surgical debridement or percutaneous drainage to survive. In patients admitted with pancreatic necrosis, without any organ failure, the mortality approaches almost zero percent. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), acute kidney failure, cardiac depression, hemorrhage, and hypotensive shock are the systemic manifestations of most severe form of acute pancreatitis.

Suppiah A et al., observed the prognostic value of the NLR in 146 patients with acute pancreatitis. They reported that elevation of the NLR during the first 48 hours of admission in hospital was associated with severe acute pancreatitis and is an independent negative prognostic indicator [8]. The most common causes and risk factors of acute pancreatitis are represented in [Table/Fig-2] [9-12]. The revised Atlanta criteria for acute pancreatitis are represented in [Table/Fig-3] [13,14]. The aim of the study was to assess the clinical profile, detection of amylase, lipase for diagnosis, progression to pancreatic necrosis and chronic pancreatitis, and NLR usage in prognostication of outcome.

Materials and Methods

The retrospective study analysed data of patients admitted with acute pancreatitis or presented to outpatient department (previous medical records) with pancreatitis between January 2011 and September 2016. Data was pooled from three hospitals in which one is a specialised gastroenterology centre. Ethical committee approval from the respective hospitals was obtained. The medical records were analysed for the demographic data (age and sex), clinical features, co-morbid conditions, investigations, mode and results of the treatment and complications of the procedures. Biochemical investigations noted at presentation were complete blood count, serum amylase (reference range: 0-100 U/L), lipase (reference range: 0-300 U/L), alkaline phosphatase (reference range: 40-130 U/L) and total bilirubin (reference range: 0-21 μmol/L), other liver function tests including alanine aminotransferase (reference range: 0-45 U/L), urea, creatinine and electrolytes, lactate dehydrogenase (reference range: 220-450 U/L) levels and serum calcium levels.

The diagnosis of pancreatitis was based on clinical features, elevation of pancreatic enzymes (amylase and/or lipase) in serum with three times greater than normal. A number of international guidelines have suggested two of the following three features are required for the diagnosis [14]:

Abdominal pain consistent with acute pancreatitis (acute onset of persistent severe epigastric pain often radiating to the back).

Serum lipase activity (or amylase activity) at least three times greater than the upper limit considered in the normal range.

Characteristic findings of acute pancreatitis on abdominal ultrasound (a CT scan or MRI is considered if the diagnosis is uncertain).

All patients were scored using the modified Glasgow Scoring System and C-Reactive Protein (CRP) levels were measured to predict the severity. Radiological imaging was performed for all patients. Abdominal ultrasound was the initial investigation and if required, abdominal CT scan was performed. A total of 339 patients fulfilled the clinical and diagnostic criteria of pancreatitis, of which 252 patients had acute pancreatitis and 78 patients had chronic pancreatitis. Nine patients of acute pancreatitis group did not have all the medical records and consents available, hence excluded. Severe Acute Pancreatitis (SAP) in the patients was diagnosed based on revised Atlanta criteria. Among 252 patients with acute pancreatitis, 38 patients had SAP.

Statistical Analysis

Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, version 18.0) was used for statistical analysis. A p-value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical data to compare patients with severe versus mild AP, and student’s t-test was used for continuous data.

Results

In our study, males constituted of 215 (85.31%) patients, while females constituted of 37 (14.68%) patients. Acute pancreatitis is about six times more common in males than females. The most common age of presentation was 21-40 years (48.80%), followed by 41-60 years age group (43.25%) [Table/Fig-4]. Among 252 patients admitted with acute pancreatitis, 237 patients (94.04%) responded to treatment and were discharged, whereas 15 patients (5.95%) died due to complications. Pancreatic necrosis was observed in 37 patients of whom eight patients died. The clinical profile and outcome in acute pancreatitis are represented in [Table/Fig-5].

Age distribution of patients.

| Age in years | Total (252) | Male (215) | Female (37) |

|---|

| <20 years | 9 | 9 | 0 |

| 21-40 years | 123 | 102 | 21 |

| 41-60 years | 109 | 96 | 13 |

| >60 years | 11 | 8 | 3 |

Clinical profile and outcome of patients with acute pancreatitis.

| Variables | Discharge (237) | Death (15) | Z score | *p-value |

|---|

| Severe Acute Pancreatitis (38) | 25 (10.55%) | 13 (86.66%) | -7.9893 | <0.001 |

| Pancreatic Necrosis (37) | 29 (12.23%) | 8 (53.33%) | -4.3612 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes Mellitus (94) | 89 (37.55%) | 5 (33.33%) | 0.3277 | 0.74 |

| Hypertension (80) | 78 (32.91%) | 2 (13.33%) | 1.5797 | 0.11 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease (15) | 13 (5.48%) | 2 (13.33%) | -1.2458 | 0.21 |

| Alcoholism (101) | 90 (37.97%) | 11 (73.33%) | -2.71 | 0.006 |

| Gall Stones (95) | 93 (39.24%) | 2 (13.33%) | 2.0078 | 0.044 |

| Intensive Care Unit Admission (97) | 82 (34.6%) | 15 (100%) | -5.0484 | <0.001 |

| Hypotension (13) | 11 (4.64%) | 2 (13.33%) | -1.4759 | 0.13 |

| Ascites (43) | 30 (12.65%) | 13 (86.66%) | -7.3891 | <0.001 |

| MODS (33) | 20 (8.44%) | 13 (86.66%) | -8.7097 | <0.001 |

| Pleural Effusion (78) | 77 (32.49%) | 1 (6.67%) | 2.098 | 0.035 |

| ARDS (19) | 9 (3.79%) | 11 (73.33%) | -9.6621 | <0.001 |

| Pseudocyst (18) | 17 (7.17%) | 1 (6.67%) | 0.0738 | 0.94 |

| Diabetic Ketoacidosis (27) | 25 (10.55%) | 2 (13.33%) | -0.3382 | 0.72 |

| Surgery (31) | 24 (10.13%) | 7 (46.67%) | -4.1784 | <0.001 |

| Laparoscopy (9) | 8 (3.37%) | 1 (6.67%) | -0.6661 | 0.50 |

*Statistically significant as p < 0.05 and statistically highly significant as p < 0.001

Statistically significant difference between patients who improved with treatment and were discharged and patients who died was observed in SAP (10.55% vs. 86.66%), pancreatic necrosis (12.23% vs. 53.33%), alcoholism (37.97% vs. 73.33%), gall stones (39.24% vs. 13.33%), intensive care unit admission (34.59% vs. 100%), onset of multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (8.43% vs. 86.66%), pleural effusion (32.49% vs. 6.67%), ARDS (3.79% vs. 73.33%) and surgical intervention (10.13% vs. 46.66%) [Table/Fig-5].

Statistically significant difference was observed between patients who improved with treatment and were discharged and patients who died were observed in amylase levels, lipase levels, CRP levels, LDH levels, CTSI score, Ranson score and Glasgow score (p<0.0001) [Table/Fig-6]. Regarding aetiology of acute pancreatitis, the causes were alcohol (n=101,40.07%), gallstones (n=95,37.69%), idiopathic (n=41,16.26%), drug-induced (n=7,2.77%), tumors (n=5,1.98%) and trauma (n=3,1.19%).

Laboratory investigations.

| Variables | Final Outcome(no. of patients) | Mean value andStandard deviation | p-value** |

|---|

| Discharge | Death | Discharge | Death |

|---|

| Amylase | 237 | 15 | 395.46±16.38 | 892.67±20.86 | <0.001 |

| Lipase | 237 | 15 | 593.16±5.98 | 981.86±9.83 | <0.001 |

| C reactive protein | 219 | 15 | 2.247±0.98 | 3.176±0.94 | 0.0004 |

| LDH | 187 | 15 | 457.38±7.88 | 697.84±11.66 | <0.001 |

| CTSI/Balthazar | 233 | 15 | 5.88±1.12 | 8.72±1.46 | <0.001 |

| Ranson score | 233 | 15 | 4.86±1.32 | 6.72±1.94 | <0.001 |

| Glasgow score | 233 | 15 | 3.64±1.08 | 5.84±1.72 | <0.001 |

p<0.05**, Significant, Chi-square test

Regarding amylase and lipase levels in relation to etiology of acute pancreatitis, the majority of patients had raised levels of both amylase and lipase (n=219,86.90%). Only lipase elevation was observed in 8.42% and 11.88% of patients with gallstone and alcohol related pancreatitis, respectively [Table/Fig-7]. Overall, raised lipase levels were seen above 95% in all patients based on aetiology.

Amylase and lipase levels in relation to aetiology of acute pancreatitis.

| Aetiology of acutepancreatitis | Elevated lipaseand amylase levels | Elevated lipaseand normalamylase levels | Normal lipase and amylase levels | Total raisedlipase levels |

|---|

| Gallstones induced (95) | 85 (89.47%) | 8 (8.42%) | 2 (2.10%) | 93 (97.89%) |

| Alcohol induced (101) | 89 (88.11%) | 12 (11.88%) | 0 | 101 (100%) |

| Idiopathic (41) | 33 (80.48%) | 6 (14.63%) | 2 (4.87%) | 39 (95.12%) |

| Drug-induced (7) | 5 (71.42%) | 2 (28.57%) | 0 | 7 (100%) |

| Tumors (5) | 4 (80%) | 1 (20%) | 0 | 5 (100%) |

| Trauma (3) | 3 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 3 (100%) |

Four patients with acute pancreatitis that had normal lipase and amylase levels and these patients were diagnosed with CT scan. A total of 500 patients were screened with investigations who presented with clinical features of acute pancreatitis. The sensitivity and specificity of lipase in our study for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis was 98.41% and 99.19% respectively. The sensitivity and specificity of amylase in our study for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis was 86.90% and 98.79% respectively.

The demographics, etiology and Imrie score comparison between favorable and poor prognosis groups are represented in [Table/Fig-8]. There were significant differences between patient age, disease etiology, amylase, lipase and Imrie scores on admission between severe and mild AP. The favorable and poor prognosis groups had significant differences in renal dysfunction as indicated by abnormal urea levels and lower glucose and albumin levels at the time of admission. The white blood cell count of the severe acute pancreatitis cohort was significantly increased compared to the favorable group (97.36% vs. 46.26%).

Demographics aetiology and Imrie score comparison between groups.

| Variables | Total (252) | Favourable (214) | Poor (38) | p-value** |

|---|

| Age | 55.6±20.4 | 53.8±21.6 | 62.4±16.4 | 0.0203 |

| Male gender | 215 (85.31%) | 183 (72.61%) | 32 (12.69%) | 0.888 |

| Cause: n (%) |

| Gallstones | 95 (37.69%) | 77 (35.98%) | 18 (47.36%) | 0.183 |

| Alcohol | 101 (40.07%) | 79 (36.91%) | 22 (57.89%) | 0.015 |

| Amylase | 443.48±18.56 | 401.36±15.24 | 831.88±18.38 | <0.001 |

| Lipase | 598.36±7.33 | 589.66±6.58 | 951.33±7.83 | <0.001 |

| Median Glasgow-Imrie score | 1 (1-2) | 1 (0-2) | 2 (2-3) | <0.001 |

| Imrie score components at day 0 |

| Oxygen (<8.0 kPa) | 29 (11.50%) | 18 (8.41%) | 11(28.94%) | 0.0002 |

| Age (>55) | 99 (39.28%) | 72 (33.64%) | 27 (71.05%) | <0.001 |

| WCC (>15 × 109/L) | 136 (53.96%) | 99 (46.26%) | 37 (97.36%) | <0.001 |

| Calcium (<2.0 mmol/L) | 2.30±0.26 | 2.32±0.32 | 2.17±0.22 | 0.0060 |

| Urea (>16 mmol/L) | 6.78±5.68 | 5.82±4.36 | 10.66±9.89 | <0.001 |

| ALT (>100 IU) | 210±18.33 | 221±21.24 | 191±17.38 | <0.001 |

| LDH (>600 IU) | 598±341 | 587±365 | 692±263 | 0.0912 |

| Albumin (<32 g/L) | 40.6±6.82 | 44.32±5.89 | 35.73±7.67 | <0.001 |

| Glucose (>10 mmol/L) | 7.3±4.56 | 6.8±5.97 | 10.8±6.38 | 0.0002 |

p<0.05**, Significant, Chi-square test

There were significant differences in other serum markers of the Imrie score except LDH. The changes in NLR from day 0 to 3 are represented in [Table/Fig-9]. The two groups were slightly comparable at time of admission, but at 1, 2 and 3 days following admission there were statistically significant differences between the favorable and poor prognosis groups. This demonstrates that in mild acute pancreatitis, the NLR is highest at the time of admission and falls towards normal levels over 2-3 days indicating reduction of the inflammatory process.

Changes in NLR from day of presentation to day 3.

| Variables | Total | Favourable | Poor | p-value** |

|---|

| NLR day 0 | 11.5 | 10.3 | 19.6 | <0.001 |

| NLR day 1 | 11.3 | 9.3 | 19.9 | <0.001 |

| NLR day 2 | 8.3 | 7.5 | 16.3 | <0.001 |

| NLR day 3 | 6.5 | 4.7 | 16.1 | <0.001 |

p<0.05**, Significant, Chi-square test

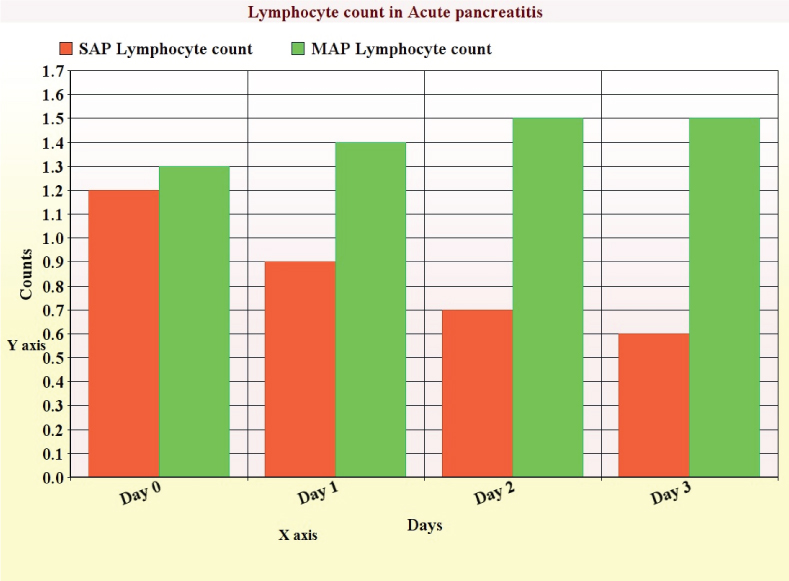

In severe acute pancreatitis, the NLR remains well above normal level for 3-4 days with peak in first or second day indicating ongoing inflammatory process [Table/Fig-9]. In patients who died due to the disorder, the NLR remained above 19 till their death indicating severe inflammation contributing to the rise. The rise of neutrophils indicates early recruitment to the inflammatory process; but, neutrophil count for the poor prognosis group is more than the baseline level in the favourable prognosis group [Table/Fig-9]. Lymphocyte count suppression occurs more predominantly in the severe acute pancreatitis group at the time of admission and continues from days 0 to 4, whereas in the mild acute pancreatitis group levels of lymphocytes rise by 24 hours after admission [Table/Fig-10].

Lymphocyte counts from day 0 to 3 in acute pancreatitis.

Discussion

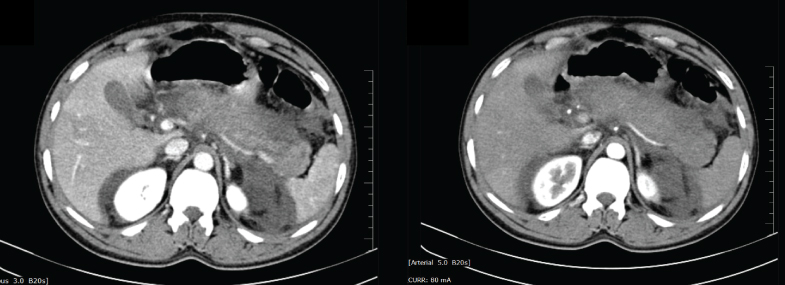

Acute pancreatitis in about 80% of patients had a mild course with the disease resolving spontaneously in approximately a week [15]. However, severe acute pancreatitis occurs in about 20% of patients, which has mortality rates of 8% to 39% [16]. The 1992 Atlanta Classification has defined SAP as the presence of organ failure or local complications such as pancreatic necrosis. Pancreatic necrosis occurs in approximately 15%-20% of patients and is typically diagnosed as focal areas of non-enhancing pancreatic parenchyma on CECT [Table/Fig-11]. Eventhough, most common aetiologies of pancreatitis are gallstones, alcohol and drugs, some patients have autoimmune disease.

CT abdomen showing diffusely enlarged pancreas with scattered non enhancing areas suggestive of necrosis, extensive peripancreatic fat stranding and moderate ascites in one of the patients.

Assessment of blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine at the time of admission has important role in prediction of morbidity and mortality but, fluid replenishment was crucial for recovery. In a study by Wu BU et al., blood urea nitrogen >20 meq/dL at the time of admission or an increase in blood urea nitrogen in the first 24 hours was associated with increased risk of mortality [17]. Lankisch PG et al., noted, that normal creatinine levels at the time of admission had a negative predictive value for severity [18]. Our study shows statistically significant differences between patients who recovered and who died due to complications.

CRP and LDH at the time of admission may be used as important prognostic markers in acute pancreatitis for predicting mortality and morbidity. The British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for the acute pancreatitis management suggest that clinical features along with increased plasma pancreatic enzymes, preferably lipase levels are important for diagnosis [19]. Many studies have shown that lipase levels are more sensitive and specific compared to amylase levels in the diagnosis of pancreatitis [20,21].

Apple F et al., noted that the sensitivity and specificity of lipase levels in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis were 85%-100% and 84.7%-99.0% [22]. The study Thomson HJ et al., reported a higher sensitivity and specificity of lipase levels compared to amylase levels for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis [21]. Similar results were reported by other studies [23-25]. Amylases catalyse the hydrolysis of amylose, glycogen, amylopectin and their hydrolysed products into simple sugars. Amylase is produced in the pancreas and salivary glands and function is to convert starches, glycogens, and polysaccharides into simple sugars. It is also produced in bacteria, yeasts, molds and plants.

Amylase is secreted by pancreatic acinar cells and is tissue specific and temperature labile than salivary amylase. Salivary amylase is produced by parotid, sweat, and lactating mammary glands. Elevations in serum amylase are mostly due to increased amylase entry into the blood stream, decreased clearance or both. Lipase catalyses hydrolysis of triglycerides to fatty acids and glycerol. Lipase is synthesised in liver, intestine, pancreas, tongue, stomach, and other cells. Lipase levels stay elevated for more duration than amylase and in acute alcoholic pancreatitis its sensitivity is more. Hence, lipase is more reliable than amylase for the initial diagnosis of acute pancreatitis [26,27].

Because of lipase sensitivity, testing is not much useful in chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Lipase testing is useful in peritonitis, strangulated or infarcted bowel, and pancreatic cyst diagnosis. Amylase levels increase within hours after the onset of symptoms and return to normal in 3–5 days. But, amylase levels may remain within normal limits in 19% of patients of acute pancreatitis [28,29]. Serum amylase levels are also elevated in abnormal glomerular filtration, salivary gland diseases, cholecystitis, acute appendicitis, intestinal obstruction and ischemia, peptic ulcer and gynaecological disorders. Some authors have proposed that both amylase and lipase tests are required for effective diagnosis [30]. Our study proves that serum lipase levels are more sensitive and specific than serum amylase levels and some cases of pancreatitis can be missed if serum amylase alone was measured.

The white cell count is an important, easily available and measurable marker for most infections and inflammatory conditions, and is included as a vital part of acute pancreatitis prognosis scoring systems i.e., Imrie, Ranson, APACHE II, and Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II). Neutrophils propagate and increase the inflammation and destruction of tissue by activation of oxygen free radicals, proteolytic enzymes (myeloperoxidase, elastase, collagenase, and β-glucoronidase), and inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α). A rapid and sustained increase in neutrophils correlates with the development of Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) and progression to MODS in severe acute pancreatitis.

Lymphocyte numbers increase during the stress and mediate further inflammatory response. The classical view, that neutrophilia is the main cause of an NLR elevation, SIRS and adverse prognosis; whereas, the lymphocyte is static doesn’t correlate with our study. Our study shows that lymphopenia occurs within 24 hours from the time of admission and ongoing lymphopenia after 24hours is an important contributor to raised NLR and poor prognosis. Our study correlates with other recent studies showing that persistent lymphopenia is an independent marker of progressive inflammation, bacteremia, or sepsis in intensive care patients and emergency admissions [31].

Uncontrolled inflammation of any disorder may precipitate lymphopenia by lymphocyte redistribution and apoptosis acceleration and lymphopenia (3 % vs. 16%) increases mortality in septic shock patients [32]. Pezzilli R et al., observed that on comparison of patients with acute pancreatitis to other acute abdominal conditions and healthy controls, lymphopenia observed on day 1 in pancreatitis persisted on days 3 and 5 following admission [33]. Takeyama Y et al., observed lymphocyte counts in 48 patients with severe acute pancreatitis and found that patients who developed infective complications, the counts were lower [34]. Ascites is less commonly caused by pancreatitis [35], but it was observed in 43 patients in our study [Table/Fig-5].

An increase in NLR has been observed to be associated with poor outcomes in benign and malignant conditions. A rise in NLR predicted in-hospital death and six-month mortality in acute coronary syndrome [36]. NLR has also been useful to predict cancer recurrence, disease-free state and survival following hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma [37] and colorectal metastases in liver [38] and hepatic transplantation for HCC. NLR has been proven to reflect SOFA and APACHE II scores. Most studies used a cut-off value for NLR of ≥5 with benign disease [36] or cancer surgery. Our study showed that Imrie scores were different in the favourable and poor prognosis groups, and can be used as a valid tool in prognostication.

Limitation

This retrospective study has the limitations in sample size and accurate calculation of incidence.

Conclusion

We put forward the following observations based on our retrospective analysis. Patients who improved and got discharged had statistically significant differences compared to SAP. CRP and LDH can be used as prognostic markers for morbidity and mortality prediction. Serum lipase levels are more sensitive and specific than serum amylase levels and some cases of pancreatitis can be missed if serum amylase alone was measured. Dynamic NLR monitoring i.e., neutrophilia and lymphopenia is cost effective, easy to perform, repeatable and accurate marker for prognosis in severe acute pancreatitis.

*Statistically significant as p < 0.05 and statistically highly significant as p < 0.001

p<0.05**, Significant, Chi-square test

p<0.05**, Significant, Chi-square test

p<0.05**, Significant, Chi-square test