Urinoma Secondary to Posterior Urethral Valve Presenting with Features of Intestinal Obstruction in a Neonate: A Case Report

Arijit Bhowmik1, Dona Banerjee2, Rajasree Sinha3, Sandeep Lahiry4

1 Assistant Professor, Department of Paediatric Medicine, Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal, India.

2 Residential Medical Officer, Department of Paediatric Medicine, Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal, India.

3 Postgraduate Trainee, Department of Paediatric Medicine, Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal, India.

4 Postgraduate Trainee, Department of Pharmacology, Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Kolkata, West Bengal, India.

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr. Sandeep Lahiry, 244 A.J.C Bose Road, Department of Pharmacology, Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research, S.S.K.M Hospital, Kolkata-700020, West Bengal, India.

E-mail: sndplry@gmail.com

Urinoma (or perirenal uriniferous pseudo cyst) occurs due to extravasation of urine in the perirenal space. Common causes include traumatic renal injury or an obstruction in the outflow tract as in a posterior urethral valve. Though rare, such diagnosis should be considered in neonates presenting with expanding cystic masses in the abdomen.

Here, we present a case of a four-day-old neonate, who presented to us with abdominal distension and bilious vomiting. The initial radiographic studies showed a cystic mass surrounding the right kidney. Urine was aspirated from the mass and Micturating Cysto-Urethrogram (MCU) showed the presence of a Posterior Urethral Valve (PUV). A diagnosis of urinoma secondary to PUV was confirmed. After relieving the obstruction by vesicostomy, symptoms of intestinal obstruction resolved. On later follow up, size of urinoma also gradually decreased.

This proves that not every case of a distended abdomen and bilious vomiting in a neonate, necessarily points towards Necrotising Enterocolitis (NEC) or intestinal obstruction.

Infant, Uretero-pelvic junction obstruction, Urine

Case Report

A term, four-day-old male child (weight: 2.7 kg) presented with progressive abdominal distension, bilious vomiting and decreased urine output. The antenatal history was insignificant since antenatal Ultrasonography (USG) data was unavailable. The mother revealed that she had a normal vaginal delivery. Breastfeeding was established at birth and the baby was subsequently discharged in good health. At home, the child was on exclusive breastfeeding. However, the parents had noticed a progressive distension of abdomen since birth with recurrent bilious vomiting after feeds and decreased urine output.

Initial examination revealed a normal cry, reflexes and tone. On admission, the baby was haemodynamically stable, and tachypnoeic (respiratory rate of 64/minutes). However, there was no chest retraction. The abdomen was distended with overlying skin tense and shiny, with distended superficial veins. Intestinal Peristaltic Sounds (IPS) were audible. There was no obvious congenital anomaly noted. Per-rectal (PR) examination did not reveal any stool or obstructive pathology. Initial investigations showed a negative sepsis screen. Serum electrolytes and renal function tests were within normal limit [Table/Fig-1]. Blood culture and antibiotic sensitivity reports reported absence of any microbial growth. The child was kept Nil Per Oral (NPO) with continuous Ryle’s tube drainage. Urinary catheterisation was performed and intravenous fluids with empiric antibiotic therapy was started.

Summary of laboratory parameters of the four-day old neonate.

| Parameters | Values | Parameters | Values |

|---|

| Haemogram | | Urine | |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 17.0 | WBC (per HPF) | <5 |

| Haematocrit (%) | 54 | RBC (per HPF) | 1 |

| MCV | 98 | Epithelial cells (per HPF) | <5 |

| Reticulocyte (%) | 0-1 | Organisms | Nil |

| WBC × 109/L | 12.2 | | |

| Neutrophil × 109/L | 5.5 | | |

| Lymphocyte × 109/L | 5.0 | Acid Base Values | |

| Monophils × 109/L | 1.1 | pH | 7.39 |

| Eosinophils × 109/L | 0.5 | PCO2 (mmHg) | 36 |

| Platelets (103/mm3) | 198 | HCO3 (mEq/L) | 22 |

| PT (second) | 12 | PO2 (mmHg) | 85 |

| aPTT (second) | 25 | Anion gap | 18 |

| FBG (mg/dL) | 210 | | |

| Capillary refill (second) | 2 seconds | | |

| Electrolytes | | Others | |

| Na (mEq/L) | 148 | Urea (mm/L) | 11.3 |

| K (mEq/L) | 5.9 | Creatinine (mm/L) | 0.3 |

| Cl (mEq/L) | 103 | CRP (mg/dL) | 5 |

| Ca (mm/L) | 1.98 | Lactate (mm/L) | 0.8 |

| Mg (mm/L) | 0.9 | Albumin (g/L) | 36 |

| | ALP (IU/L) | 42 |

Abbreviations: WBC, White blood cell; RBC, Red blood cell; HPF, High power field; PT, Prothrombin Time; aPTT, Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time; FBG, Fasting blood glucose; CRP, C-reactive protein; ALP, Alkaline phosphatase.

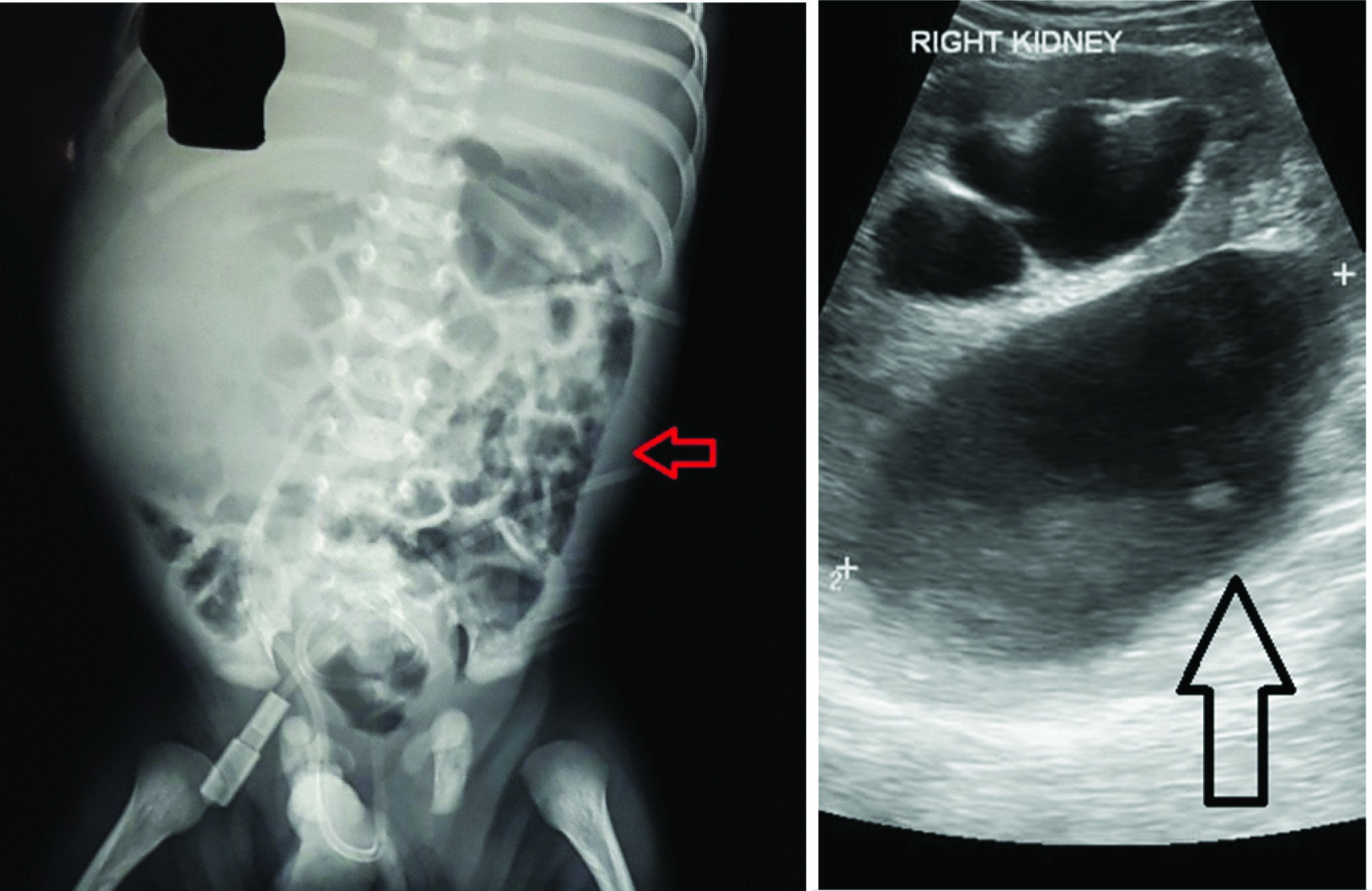

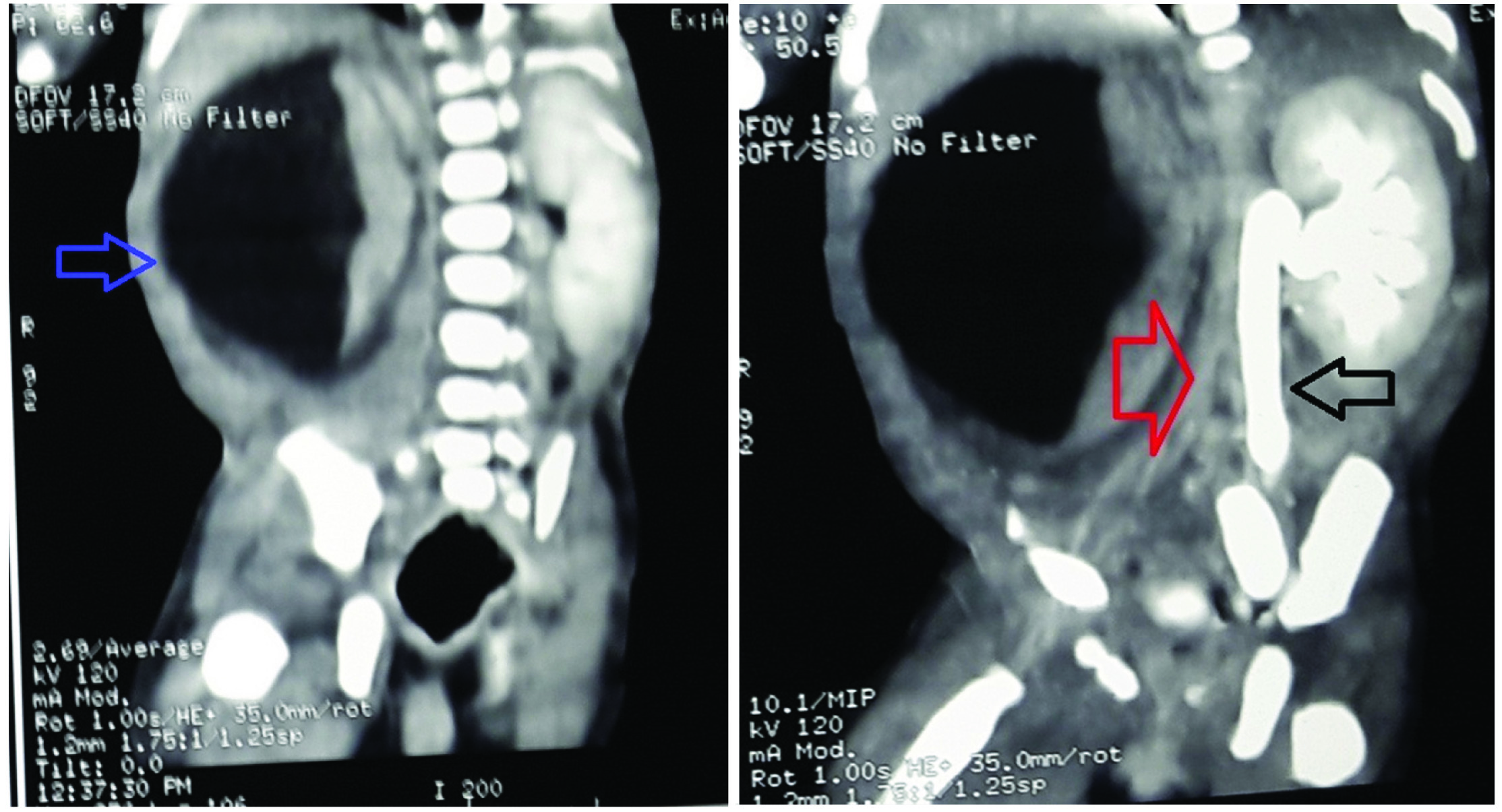

The chest skiagram was normal. Abdominal X-ray revealed a ‘full right flank’ with an increased radiodensity noted at right abdomen along with displaced bowel loops towards the left side, raising suspicion of an intraabdominal mass lesion in right abdomen [Table/Fig-2a]. USG whole abdomen showed a large cystic collection [Table/Fig-2b]. Measurements included: Right kidney: 4.4 cm, Left Kidney: 3.8 cm. Bilateral renal cortical echogenicity was raised with altered Cortico-Medullary Differentiation (CMD). There was no ascites and other abdominal viscera were normal. Axial Computerised Tomography (CT) scan showed a hypodense collection in right abdomen encircling right kidney [Table/Fig-3a]. The collection itself was well encysted; no free fluid in abdomen was present. On delayed scan, no contrast excretion was noted at right side. Left kidney and left sided pelvi-calyceal system with ureter showed normal contrast excretion but with dilatation of pelvis and ureter [Table/Fig-3b].

a) X-ray Abdomen showed ‘Full right flank’ suggestive of urinoma, with increased radiodensity noted at right abdomen along with displaced bowel loops towards left side (red arrow); b) USG whole abdomen showed a large cystic collection (black arrow) around the right kidney.

a) CT abdomen showed large cystic collection (blue arrow) encircling right kidney, the right ureter seems to be compressed by the pressure effect of the collection; b) Delayed CT scan showed no contrast excretion noted at right side (red arrow). Left kidney and left sided pelvi-calyceal system with ureter showing normal contrast excretion but with dilatation of pelvis and ureter (black arrow).

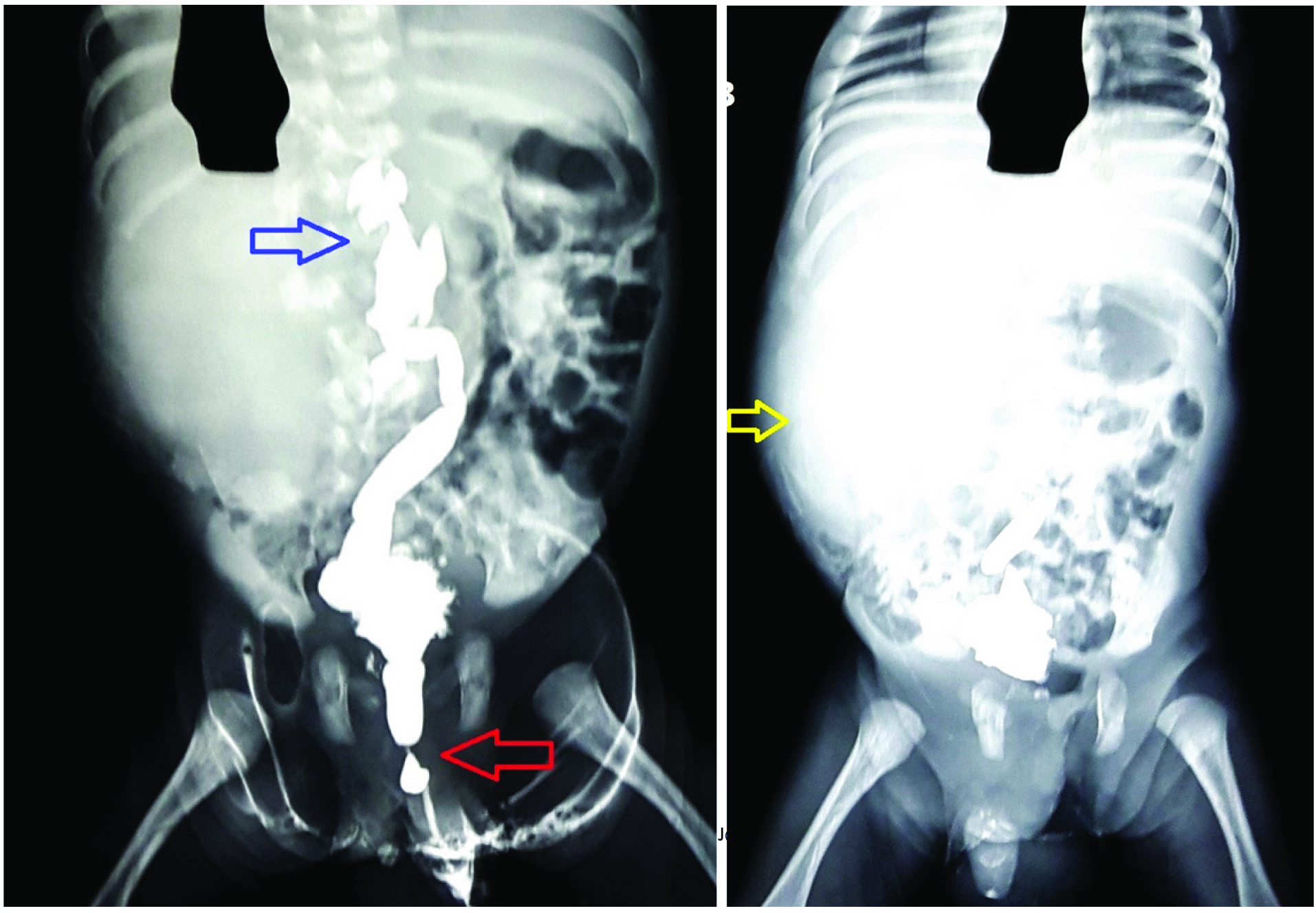

Diagnostic fluid aspiration from the mass, revealed a straw coloured fluid, which had an acidic reaction to litmus paper. Fluid biochemistry showed a creatinine value of 221.8 mg/dL, confirmed it to be urine. An Micturating Cysto-Urethrogram (MCU) was done next, as the renal function was within normal limit. It showed an irregular bladder with tiny diverticula. A grade IV: Vesico-Ureteral Reflux (VUR) with dialation of ureter was noted on the right side [Table/Fig-4a]. No VUR was noted on the left side in the present film. Posterior urethra was fusiformly dilated with abrupt narrowing suggesting a Posterior Urethral Valve (PUV). Diffuse spreading of dye (extravasation) noted in postvoid MCU confirmed right sided VUR [Table/Fig-4b].

a) Contrast imaging showed bladder wall irregular with tiny diverticula noted, Grade 4 VUR noted at right side (blue arrow), no VUR on left side in present film. Posterior urethra fusiformly dilated with abrupt narrowing suggesting PUV (red arrow); b) Postvoid MCU film showing diffuse spreading of dye on the right side (yellow arrow).

Thus, the final diagnosis was right sided urinoma secondary to posterior urethral valve with unilateral grade IV reflux with normal kidney function but causing extra intestinal compression of gut with features of intestinal obstruction. On day four post admission, the neonate had undergone a percutaneous nephrostomy, resulting in drainage of approximately 400 mL of urine. Resection of PUV was done subsequently. Repeat USG confirmed reduction in the peri-renal and subcapsular collection, with improved symptomatology. The neonate made a gradual recovery and was discharged from the hospital. Antibiotic prophylaxis was started. On one month follow up, baby was in good health with marked regression of urinoma size on USG (2.3×1.5 cm).

Discussion

The foetal urinoma or a perirenal uriniferous pseudo cyst occurs due to extravasation of urine in the perirenal space. The common causes for such extravasation can be trauma to kidney or an obstruction in the outflow tract as in a posterior urethral valve, ureteric obstruction or a pelvi-ureteric junction obstruction [1]. The incidence of posterior urethral valves is between 1 in 5000:8000 [2]. Upto 10-15% of neonates with a PUV may have a secondary urinoma [3]. In such cases, progressive renal deterioration is common and 25-40% patients develop renal failure [4-6]. Fluid and electrolyte imbalance or respiratory compromise (secondary to lung hypoplasia) can also occur [7].

Such obstruction causes severe renal parenchymal injury and in order to preserve the foetal and neonatal renal function, various “pop-off” valve mechanism like unilateral reflux and dysplasia, urinary extravasation (urinoma, urinary ascites) and congenital bladder diverticula has been advocated which are present in about 30% of patients with PUV [8] with disputed effect on renal function with some retrospective studies showing a protective impact [9].

The ‘mass effect’ of urinoma may result in a myriad of symptoms [10]. It may present with features of respiratory distress, abdominal distension etc., [11]. Urinoma presenting with symptoms mimicking intestinal obstruction is very rare. Only a few case reports mentioned presentation of urinoma with recurrent bilious vomiting and abdominal distension [12,13]. In this case, the neonate presented with abdominal distension with bilious vomiting. The differential diagnosis made in such case is usually surgical with causes being duodenal atresia, malrotation with volvulus, jejunoileal atresia, meconium ileus or NEC [14]. Delay in treatment initiation may cause bowel ischemia [15].

Initially, we had similar suspicion but the USG and CT scan proved beyond doubt that the cause of obstruction is an extra intestinal cyst, later proved to be due to an urinoma secondary to a PUV. Interestingly, majority cases of urinoma reported have right side affected [16].

Conclusion

Neonates presenting with abdominal distension and bilious vomiting is generally secondary to intestinal atretic lesion, malrotation, NEC etc. This presentation secondary to extra intestinal compressive mass is a rare entity. In our case, it was a localised form of urinary extravasation, presenting with features of intestinal obstruction. Though rare, a diagnosis of urinoma should be considered in neonates presenting with rapidly expanding cystic masses in the abdomen.

Abbreviations: WBC, White blood cell; RBC, Red blood cell; HPF, High power field; PT, Prothrombin Time; aPTT, Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time; FBG, Fasting blood glucose; CRP, C-reactive protein; ALP, Alkaline phosphatase.

[1]. Silveri M, Adorisio O, Pane A, Zaccara A, Bilancioni E, Giorlandino C, Fetal monolateral urinoma and neonatal renal function outcome in posterior urethral valves obstruction: the pop-off mechanismPediatr Med Chir 2002 24(5):394-96. [Google Scholar]

[2]. Atobatele MO, Oyinloye OI, Nasir AA, Bamidele JO, Posterior urethral valve with unilateral vesicoureteral reflux and patent urachus: A rare combination of urinary tract anomaliesUrol Ann 2015 7(2):240-43. [Google Scholar]

[3]. Cho A, Khan A, Chandran H, Carroll D, Bilious vomiting in two neonates due to an urinoma secondary to posterior urethral valvesJ Ped Surg Case Rep 2015 3(12):541-44. [Google Scholar]

[4]. Parkhouse HF, Barratt TM, Dillon MJ, Duffy PG, Fay J, Ransley PG, Long-term outcome of boys with posterior urethral valvesBr J Urol 1988 62(1):59-62. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Reinberg Y, de Castano I, Gonzalez R, Prognosis for patients with prenatally diagnosed posterior urethral valvesJ Urol 1992 148(1):125-26. [Google Scholar]

[6]. Bhadoo D, Bajpai M, Panda SS, Posterior urethral valve: Prognostic factors and renal outcomeJ Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg 2014 19(3):133-37. [Google Scholar]

[7]. Macpherson RI, Leithiser RE, Gordon L, Turner WR, Posterior urethral valves: an update and reviewRadiographics 1986 6(5):753-91. [Google Scholar]

[8]. Rittenberg MH, Hulbert WC, Snyder HM 3rd, Duckett JW, Protective factors in posterior urethral valvesJ Urol 1988 140(5):993-96. [Google Scholar]

[9]. Oktar T, Salabaş E, Kalelioğlu İ, Atar A, Ander H, Ziylan O, Fetal urinoma and prenatal hydronephrosis: how is renal function affected?Turk J Urol 2013 39(2):96-100. [Google Scholar]

[10]. Lee E, Thonell S, Posterior urethral valves causing urinomas: Two case reportsJ Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2002 46(1):101-05. [Google Scholar]

[11]. Hoffer FA, Winters WD, Retik AB, Ringer SA, Urinoma drainage for neonatal respiratory insufficiencyPediatr Radiol 1990 20(4):270-71. [Google Scholar]

[12]. Moore DP, Goodson M, Plucinski T, Urinoma: an unusual case of emesis in a brain-injured childPediatr Rehabil 1997 1(3):185-89. [Google Scholar]

[13]. Kimura K, Loening-Baucke V, Bilious vomiting in the newborn: rapid diagnosis of intestinal obstructionAm Fam Physician 2000 61(9):2791-98. [Google Scholar]

[14]. Prasad GR, Aziz A, Abdominal plain radiograph in neonatal intestinal obstructionJ Neonatal Surg 2017 6(1):6 [Google Scholar]

[15]. Jiwane A, Holland AJA, Soundappan SSV, Arnold J, An unusual cause of bilious vomiting in a neonateJ Paediatr Child Health 2008 44(12):747-49. [Google Scholar]

[16]. Yitta S, Saadai P, Filly RA, The fetal urinoma revisitedJ Ultrasound Med 2014 33(1):161-66. [Google Scholar]