The World Alzheimer Report 2015 reported that 46.8 million people worldwide are living with dementia in 2015, and it is estimated that this number will almost double every 20 years and till date there are no curative measures for dementia [1,2]. Therefore, the public, family members and health care professionals play important roles in providing critically needed care for these people. Thus, the level of knowledge and attitudes towards people with dementia is an important matter of concern. Knowledge towards dementia is defined as the ability to comprehend through facts, information and skills. Attitudes towards dementia are positive or negative judgments of a belief that often effects a person’s feelings and behaviours in a way that is in line with the judgment [3]. It is important to have adequate knowledge and positive attitudes towards people with dementia to ensure a better quality of care and also to protect the quality of life of the caregiver [4,5].

Studies regarding knowledge and attitudes towards dementia had been done among the general public [6-10], mental health professionals [11-14], family caregivers [15,16] and students [4,17,18]. Particularly, it is important to study the knowledge and attitudes towards dementia among college and university students as they are the next generation to uphold the responsibility for caring their family members. For students who enroll in courses related to mental health services, they are expected to become professional caregivers. Even if they do not have family members with dementia or work in mental health services professionally, they will likely be a point of reference for family members and friends of their own with dementia [19]. Till date there has been no review of research specifically focusing on college and university students on this area. Its therefore important to recognize and review the literature of knowledge and attitudes towards dementia among college and university students.

Materials and Methods

Past studies on knowledge and attitudes towards dementia among students were identified using the following electronic databases: Academic Search Complete, Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection, Medline Complete, SocINDEX with full text, Education Research Complete and Education Resources Information Centre (ERIC). Papers published since January 2010 until March 2017 are selected and reviewed.

Key words used in the search were “knowledge,” or “attitude,” or “perception,” or “opinion,” or “belief,” and Dementia,” or “Alzheimer’s,” and “students.” These key words were selected based on the most frequent terms used in the papers. The inclusion criteria were published papers from January 2010 until March 2017, peer-reviewed, English language, focusing on knowledge, attitude, perception, opinion or beliefs towards Dementia or AD and studies that include college and university students as the sample. The exclusion criteria are papers published before January 2010, papers other than English language, topics not related to knowledge, attitude, perception, opinion or beliefs towards Dementia or AD disease and the sample of the study does not include college and university students. Studies using school students as a sample are also excluded from this study.

Results

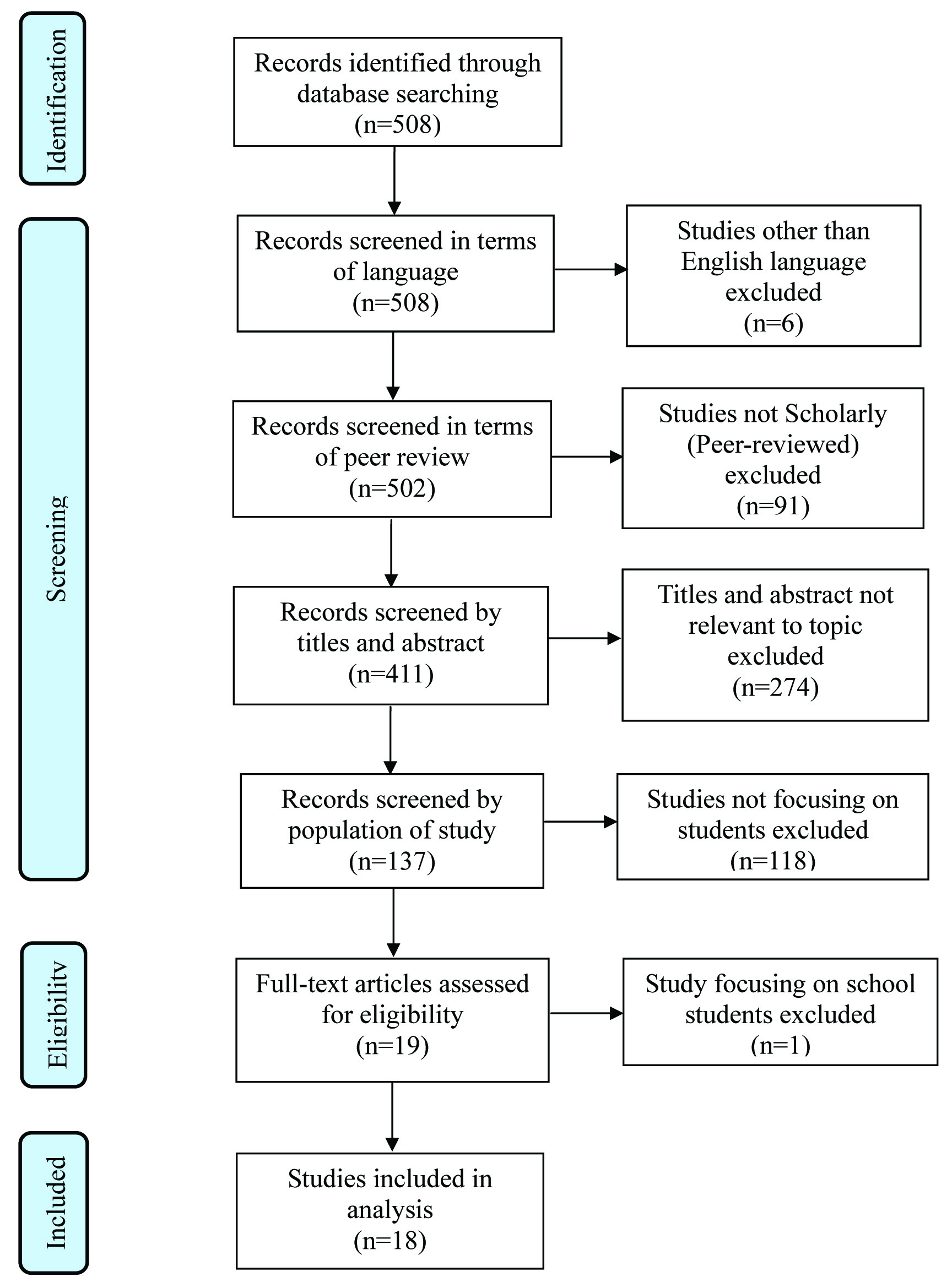

Overall, the initial search strategy yielded 508 papers, 230 from Academic Search Complete, 85 from MEDLINE Complete, 68 from Educational Research Complete, 54 from Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection, 51 from SocINDEX with full text, and 20 from ERIC. After limiting the search findings to English language, six papers were excluded, yielding 502 papers. After limiting to Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) journals, 411 papers were left. Subsequently, 274 papers were excluded after screening as titles and abstracts were not related to knowledge, attitude, perception, opinion or beliefs towards dementia or AD disease and 118 papers excluded as the studies did not focus on students, leaving 19 papers. One paper was then excluded as the study focussed on adolescent school students rather than university or college students. This leaves the number of papers eligible to 18 papers. The [Table/Fig-1] shows the PRISMA flow diagram for the review.

PRISMA flow diagram of study.

The [Table/Fig-2] represents the following important features of relevant studies: 1) Author, year published and country; 2) objective of study; 3) number of participants and course enrolled; 4) study design; 5) assessment tools used in the study; 6) results; and 7) discussion key points [4,17-33].

Review summary of published studies on knowledge and attitudes towards dementia among college and university students [4,17-33].

| Author /Year / Country | Objective | Sample | Design | Assessments | Results | Discussion |

|---|

| Kaf WA et al., USA [4] | Test students’ attitudes towards older adults and dementia in interdisciplinary service learning experience (SL) | A total of 19 audiology and 24 speech language pathology (SLP) students enrolled in SL experience; 14 audiology and 18 SLP did not | Non-randomized pre/post-test group comparison design (Qualitative and quantitative) | Kogan’s Attitudes Toward Old People Scale and pre-post SL journal entries | Those who enrolled in SL experience showed more positive attitudes (F = 21.923, p?.001, n2=.360) | Clinical hands-on experience with people with dementia improved students’ attitude |

| George DR et al., USA [17] | Evaluate whether participation in a creative group-based storytelling program would improve students’ attitudes towards dementia | A total of 15 fourth-year medical students | Comparison of qualitative data pre and post intervention | Subjective narrative evaluations of the course | Students’ attitudes became more positive and shift in perspective towards persons with ADRD | Creative activity to improve attitudes rather than confined to clinical encounters |

| Jansen BDW et al., UK and USA [18] | Explore attitudes of final year students towards people with dementia | A total of 368 final year medical, nursing and pharmacy undergraduate students | Cross-national cross-sectional survey | Attitudes to Dementia Questionnaire | US nursing students indicated more positive attitudes (ADQ; 80.86±4.31 out of 95 points), higher Hope (30.50±3.36, out of 40 points) and preferred Person-centred approach (50.3 ±2.96, out of 55 points) | Importance of a holistic, interdisciplinary and integrated approach to care |

| Eshbaugh, USA [19] | Examine level of knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and identify gaps of knowledge among college students | A total of 200 college students | Questionnaire survey | Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale (ADKS); Self-reported Alzheimer’s Knowledge | Approximately 70 % students unaware high cholesterol and blood pressure as risk factors for AD; those who had coursework pertaining to AD had greater knowledge; ADKS (21.63±4.49 out of 30) | Provides basis for educational programs that target gaps in knowledge |

| Garrie AJ et al., USA [20] | To assess participation in poetry workshop with people with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) | A total of 11 medical students | Comparison of quantitative and qualitative data pre and post intervention | Dementia Attitudes Scale (DAS) and Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis | Attitudes significantly improved after poetry workshop, particularly in terms of ‘comfort’ and ‘knowledge’; DAS scores increase from 107.09±11.85 to 121.82±10.38 out of 140. | Poetry intervention revealing the creativity of persons with ADRD |

| Kwok T et al., Hong Kong [21] | To evaluate the knowledge of dementia among health and social care | A total of 242 final year undergraduates from social work, nursing, occupational therapy, medicine | Cross-sectional survey | Modified version of Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Test (ADK); General Self-Efficacy Scale | Generally poor knowledge of dementia; ADK score was 7.4±3.7 out of 20 points | Hours of teaching about dementia are associated with level of dementia knowledge |

| Shin JS et al., South Korea [22] | Assess knowledge about dementia | A total of 148 undergraduate nursing students | Cross-sectional survey | Korean version of Dementia Knowledge Questionnaire (DKQ) | Level of knowledge reasonably good; DKQ score was 10.26±1.24 out of 12 points. Relatively low on prevention, treatment and causes with correct rate of 78.6% and 85.4% respectively. | Integrating dementia educational courses and clinical experience improves knowledge |

| Rawlins J et al., Trinidad and Tobago [23] | Compare knowledge and attitudes of pre-healthcare and non-medical undergraduate students towards patients with AD | A total of 369 pre healthcare and 322 non-medical students | Cross-sectional survey | Self-developed 28 item questionnaire | Pre healthcare students had higher knowledge (mean score: 39.95) and 54.47% showed satisfactory attitudes than non-medical students | Higher knowledge and exposure towards AD creates more understanding, empathetic and caring attitudes |

| Rust TB and See STK, Canada [24] | Examine beliefs about aging and AD in cognitive, social and physical domains | A total of 140 undergraduate students | Not specified | Self-developed 46 item questionnaire | Students perceived AD as a disease that affects cognitive but enhances physical prowess | Modifying stereotyped behaviour towards people with AD by documenting beliefs |

| Eccleston CEA et al., Australia [25] | To investigate dementia knowledge before and after a supported placement in a residential aged care facility | A total of 99 second-year nursing undergraduate students | Pre-post control- intervention questionnaire study. | Dementia Knowledge Assessment Tool 2.0 | Nursing students had a poor understanding about dementia. However their knowledge improved after participation at an intervention residential aged care facility | Well-supported clinical placement at a residential aged care facility can improve nursing students’ knowledge of dementia |

| Beer LE et al., USA [26] | To examine perceptions and communication ability through communication training with patients with advanced dementia | A total of 47 nursing aide students | Experimental study; Post-test only randomized control group design | Self-developed questions | Training effective for understanding of residual cognitive abilities and need for meaningful contact. However the training was not effective to support nurses’ comfort level and perceived skills in working with dementia population. | Suggests the need to transform how caregivers are trained in communication techniques |

| Kada S, Norway [27]. | To assess dementia-related knowledge in health and social care students | A total of 321 undergraduate students from various disciplines in their final year of study but prior to graduation | Descriptive study | The Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale (ADKS) | Moderate dementia knowledge base (ADKS mean score: 23.51 out of 30) among health and social care students and ignorant many facts about dementia | Current dementia curriculum should be evaluated |

| Roberts HJ and Noble JM, USA [28] | To assess attitudes toward dementia through participation in non clinical, art-centred experiences | A total of 167 preclinical first year medical students | Pre and post pilot intervention study; baseline assessments functioned as the control condition | Dementia Attitudes Scale (DAS) | Overall, students demonstrated greater increase on DAS (8.4 point increase, p < 0.001) and DAS subdomain of comfort (5.9-point increase, p < 0.01) compared with dementia knowledge (2.6-point increase, p < 0.05). | Art-centred experiences could improve understanding of existing community based programs |

| Jefferson AL et al., USA [29] | To evaluate the Partnering in Alzheimer’s Instruction Research Study (PAIRS) Program and its effectiveness in enhancing medical education as a service-learning activity | A total of 45 first year medical students | Pre post program dementia knowledge tests (quantitative) and a post-program reflective essay (qualitative) | The Buddy ProgramTM Dementia Knowledge Test, The Boston University PAIRS Program Dementia Knowledge Test; reflective essays | Buddy ProgramTM and PAIRS program significantly improved knowledge of dementia with increase of 2.4 point (p < 0.001) and 4.5 points (p < 0.001) respectively. | Medical schools must provide sufficient opportunities for medical students to participate in service-learning |

| Zimmerman M, Germany [30] | To assess the effectiveness of a medical humanities teaching module focusing on pharmaceutical care for dementia patients | Pharmacy students; Sample size not stated | Pre and post intervention study | Self-developed questionnaire | Around 50% students reported an increase in knowledge and 40% increase in empathy and 31% felt increase of awareness towards patient and caregivers | Enhances discussion on the value of integrating the medical humanities into the curricula of pharmacy and other health sciences |

| Scerri A and Scerri C, Malta [31] | To assess knowledge and attitudes of nursing students towards dementia | A total of 280 full-time diploma and degree nursing students | Questionnaire survey | Alzheimer’s disease Knowledge Scale; Dementia Attitude Scale. | Overall students scored adequate knowledge as measured on ADKS; mean score of 19.36±3.30 (range 10–28) and equivalent to 64.5% of correct answers. Also, students showed positive attitudes towards dementia, DAS; 103.51±13.43 (range 20-140) | Knowledge and attitudes could improve by improving clinical experience |

| Kimzey M and Mastel-Smith B USA [32] | To determine the effect of different educational experiences on nursing students’ knowledge and attitudes toward people with AD | A total of 94 senior level nursing students | Convergent mix method design; quantitative and qualitative | Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale (ADKS); Dementia Attitudes Scale (DAS) | The Alzheimer’s disease clinical group students showed significant increase in ADKS score of 2.16 point (p < 0.05) and 12.14 points (p < 0.05) in attitudes (DAS). | Experiential learning in the form of clinical placements increased knowledge and improved attitudes |

| McCaffrey R et al., USA [33] | To test understanding of roles with Alzheimer’s patients through inter-professional approach to clinical education | A total of 80 second-year medical; 82 family nurse practitioner students | Two-group treatment/ control pre-test post-test design | Self-developed items; investigator-created semantic differential scale items | Nurse students gained higher levels of knowledge (F=4.69, p < 0.05) and medical students gained more positive attitudes (F=4.90, p < 0.05) towards dementia. | Students may benefit from observing and working on inter-professional teams |

It was essential that information gathered from the studies in this review would provide directions for future research. The year published was important to focus on current research {[Table/Fig-2]; Column 1}. The country in which the research was done would provide information on which region studies have been mostly done and which regions need more research {[Table/Fig-2]; Column 1}. The objective of study was to identify which studies focussed on knowledge, attitudes towards dementia, or both {[Table/Fig-2]; Column 2}. Number of participants and course enrolled were identified to give a sense of the sample covered by these studies, larger sample sizes would give more reliable results than smaller sample sizes and whether certain courses enrolled by students would have an impact on the knowledge and attitudes {[Table/Fig-2]; Column 3}. Study design is important to show the range of methodological approaches used in previous studies {[Table/Fig-2]; Column 4}. The assessment tools used in the study are essential in identifying the studies that used psychometrically sound instruments to measure the variables. This was of particular interest in this review as a way of identifying which scales that have been validated in the use of respective countries {[Table/Fig-2]; Column 5}. Results and discussion is to highlight the level of knowledge and attitudes of students towards dementia and to identify the directions of future research and clinical practice {[Table/Fig-2]; Column 6 and 7}.

A total of 18 studies from 2010 to 2017 fulfilled the reviews inclusion criteria on the knowledge and attitudes towards dementia among college and university students. Out of the 18 papers, nine (50%) studies were conducted in United States of America (USA; [4,17,19,20,26,28,29,32,33]). Three papers were from Europe, which are Norway [27], Germany [30] and Malta [31]. There are two papers studied in Asia, specifically in Hong Kong [21] and South Korea [22]. Other countries include Trinidad and Tobago [23], Canada [24] and Australia [25]. Only one study was conducted a cross-national which include USA and United Kingdom [18].

Six papers focussed on studying attitudes [4,17,18,20,24,28]. Out of these six studies, one paper [24] studied ‘beliefs’ rather than ‘attitudes’ or ‘knowledge,’ but this study is categorized under ‘attitudes’ for the purpose of this review, as Wilkinson and Ferarro [34] stated that ‘beliefs are associated with attitudes, in which attitudes are positive or negative evaluations of beliefs.’ Seven papers studied knowledge [19,21,22,25,27,29,30] and the remaining included both knowledge and attitudes [23,26,31-33] in their studies.

Only one study did not report the number of sample size [30]. Among the remaining 17 papers, a total of 3,105 participants were studied, in which all of them were college or university students. The sample sizes ranged from 11 [20] to 691 participants [23]. A large majority of the students enrolled in courses related to clinical healthcare services such as medical [17,18,20,21,23,27-29,33], nursing [18,21,22,23,25,27,31-33], audiology and speech [4], pharmacy [18,23,30] occupational therapy [21,27] and physiotherapy [27]. Other healthcare service courses include social work [21,27], family services [19], psychology [19] and social education [27]. Only few studies included students who enrolled in courses not related to healthcare services [19,23]. One study did not report the major course enrolled by the students, but the participants were undergraduate students who joined an introductory psychology class [24].

The study design varied across the studies reviewed. Ten of the studies (55.56%) were experimental intervention programmes, in which nine papers included pre and post measurements [4,17,20,25,28-30,32,33] and one study was a post-test only randomized control group design [26]. Among these ten intervention studies, five used quantitative measures [20,25,26,28,30], two used qualitative [17,33] and another three used a mix method design [4,29,32]. Seven studies (38.89%) were questionnaire surveys, in which four of them are cross-sectional studies [18,21-23] and the remaining three are descriptive questionnaire surveys [19,27,31]. One study did not report the study design [24].

Among the ten intervention programmes, seven studies focussed primarily on hands-on experience and exposure with dementia patients. These studies are the creative group-based story telling with dementia patients [17], interdisciplinary service learning experience in a nursing home residents with dementia [4], poetry workshop with dementia people [20], placement in a residential aged care facility [25], communication training with patients who have advanced dementia [26], museum-based art-centered program with dementia patients and caregivers [28] and Partnering in Alzheimer’s Instruction Research Study (PAIRS) ProgramTM [29]. One study focussed on medical humanities teaching module as part of the pharmacy course [30], but did not involve hands-on experience with dementia patients. Another experimental study included two experimental groups, one which went through an AD online module but with no clinical experience, and another which engaged with people with AD at a memory care unit and dementia day centre [32]. Another study focussed on an interprofessional approach to clinical education between nursing and medical students [33].

There was also a large variety in the assessments used to measure the variables. The most popular instrument used to measure attitudes is the Dementia Attitudes Scale [35], which is used in four studies [20,28,31,32]. In assessing knowledge, the most frequently used instrument is Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale [36], also used in four studies [19,27,31,32]. A number of studies reported using self-developed questionnaire to measure attitudes [23,24,26,33] and knowledge [19,23,30,33]. Other instruments used include Attitudes to Dementia Questionnaire {ADQ; [18,37]}, modified version of Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Test {ADK; [21,38]}, Korean version of Dementia Knowledge Questionnaire [22,39], Dementia Knowledge Assessment Tool 2.0 {(D-KAT2; [25,40]}, The Buddy Program Dementia Knowledge Test [29,41] and The Boston University PAIRS Program Dementia Knowledge Test [29,42].

Results of the intervention studies revealed that the intervention programmes improved student’s attitudes [4,17,20,26,28]. Qualitative findings suggest that students felt surprised that they actually enjoyed spending time with dementia patients and the experience left a personal impact on them [17] as well as feelings of increased hope, humanity, creativity, confidence and comfort in interacting with dementia patients [20]. They were also surprised at the effectiveness of management techniques which were non-biomedical in nature [20]. Communication training with dementia patients was effective in increasing the understanding of the skills in approaching, talking, understanding verbal and non-verbal cues, as well as assessing pain indicators. However, the effectiveness had limitations in terms of increasing comfort level or perceived skills [26].

Students knowledge also improved through the intervention programmes [25,26,29,30]. Communication training helped students understand the emotional aspect, needs and abilities of patients who have dementia [26]. Qualitative findings suggest that the program was beneficial in integrating scientific knowledge and how to practically apply the knowledge in real settings. One student wrote, “tie all my knowledge together while providing much more data – both scientific and experience related” ([29], p.4). It also revealed the humanistic side of the disease, as one student wrote, “My buddy allowed me to see Alzheimer’s through his eyes (and) to better understand his difficulties, frustrations and concerns” ([29], p.5).

In a comparison, between the group of students who experienced engaging with people with Alzheimer’s disease and students who only completed the online module (without engagement with Alzheimer’s disease people) or had no dementia-specific intervention, those who engaged with Alzheimer’s disease patients experienced increased knowledge and improved attitudes [32]. An inter-professional education programme also improved students knowledge and attitudes towards Alzheimer’s disease as well as improving attitudes towards inter-professional teamwork and collaboration. A medical student wrote, “now I have a better picture of how different members function in the team,” while a nurse practitioner students wrote, “the physician and nurse worked very well as a cohesive team” ([33], p.536).

Findings from questionnaires survey shows that the attitudes of students are positive [18,31] and students believe that dementia affects cognitive but enhances physical prowess [24]. In terms of knowledge, findings reveal diverse results. Studies report that the knowledge was poor [21], moderate [27], adequate [31] and reasonably good, but relatively low on prevention, treatment and causes [22]. Some studies found that students reported lower understanding of risk factors [19,27] and causes [27] related to dementia, such as high blood pressure and increased cholesterol [19]. However, most students understood that it is not effective to remind people with Alzheimer’s disease that they are repeating themselves and most knew that Alzheimer’s impacts short-term memory worse than long-term memory [19].

Medical students scored high on assessment and diagnosis domain [27], while nursing students showed more positive attitudes and preferred the Person Centred approach than medical and pharmacy students [18]. Another result showed that those who enrolled in courses pertaining to dementia or AD showed more knowledge [19] and more positive attitudes [23] than those who did not. Higher grade level and more clinical experience were associated with increased knowledge towards dementia [22,23,31] and more positive attitudes [4,23,31]. Age and previous care of dementia patients were also associated with higher knowledge and positive attitudes [31]. Hours of teaching dementia related courses were also related to the level of dementia knowledge among students [21].

Discussion

It is evident from this review that most studies highlight the importance of improving the current curricular module of courses related to dementia [4,18,19,21-27,29,30,32,33]. It shows that specific modules on dementia that focuses on understanding dementia theoretically and practically is important in improving student’s knowledge and attitudes towards people living with this disease. The modules must target in improving the gaps of knowledge in understanding dementia which, as highlighted in previous research are prevention methods [22], risk factors [19,27], causes [22,27] and treatment [22].

This review also sheds light on the importance of integrating these modules with clinical hands-on experience to expose students with people living with dementia. Studies have consistently shown that students who have experience and exposure with dementia patients have higher knowledge [20,22,23,25,29,30,32,33] and more positive attitudes [4,17,20,23,28,32,33]. We now understand that students who have the direct experience report better attitudes as it leaves them a personal impact [17], increase confidence, comfort [20] and understanding on how to approach and interact with the patients [26]. In terms of knowledge, students learn the humanistic side of the disease [26] and discover the integration between scientific findings and practical experience [29].

Another interesting finding from this review may direct future plans to incorporate creative activities into the service learning modules, rather than confined to clinical encounters. Studies have shown that creative programmes such as storytelling [17], communication training [26], arts [28] and poetry [20] have been successful in connecting the bridge between students and dementia patients, particularly in terms of knowledge regarding cognitive abilities and need for meaningful contact [26], comfort [20,28] and positive attitudes [17,28].

One study found that medical students are better in assessment and diagnosis while nursing students are more Person Centred in nature [18]. This indicates that different courses focus on different perspectives about the disease and also shows that there are different gaps of knowledge in each course. Hence, another important finding in the literature is how the combination of interprofessional approach between different courses in clinical education helps students to observe and work on inter-professional teams during their clinical placements. Competency in interprofessional collaboration is vital to ensure quality and comprehensive care for dementia patients.

It is difficult to standardize the results of the quantitative research findings into categorical measurements (positive or negative attitudes; low, moderate or high knowledge) as a variety of assessments have been used to measure the variables and different assessments have different cut-off scores. Some studies even use self-developed questions which are not validated [23,24,26,30,33]. Moreover, not all papers report findings in a categorical manner. Based on the current literature, most papers have used the Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale [19,27,31,32,36] to measure knowledge and Dementia Attitudes Scale [20,28,31,32,35] in evaluating attitudes. Future researches are suggested to use these scales whenever possible to obtain standardized results.

It is important to note that most studies in looking at knowledge and attitudes among college and university students towards dementia were conducted within American and European population. Only few studies involved higher education students from other parts of the world. Hence, it is necessary to report that the findings are limited to a certain population and must not be generalized to other societies and communities which may apprehend different values and understandings of the disease. Thus, more research regarding knowledge and attitudes towards dementia are needed in other continents including Asia and Africa.

Majority of the samples in the studies are medical and nursing students and very few studies focussed on students from other important healthcare field, such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy etc. Therefore, findings in these studies might not be generalizable to the whole clinical healthcare student population, but limited to medical and nursing courses only. It is vital to study knowledge and attitudes among all courses related to dementia as these students will be the professionals working with dementia patients in their future practice.

Limitation

The main strength of present review is the focus on college and university student’s knowledge and attitude towards dementia which is first kind of review in the field. As part of synthesizing previous findings, present review highlighted the most common lacking in students knowledge and attitudes about dementia. Furthermore, this review also indicates that exposure to theoretical and practical aspect of dementia would facilitate better understanding and attitude towards dementia among students. However, present review has limitation whereby this review only focuses on papers published since 2010, thus, not fully reflects the entire knowledge in the field.

Conclusion

Considering the increasing population of people with dementia, there is a need for college and university students, particularly healthcare service students to gain appropriate knowledge and attitudes towards people living with dementia. They will be the future generation that will be directly working with this population. Current evidence suggests that there are room for improvement in the course modules. This review provides basis for future planning to improve the current curricular by addressing the gaps in knowledge, incorporating hands-on clinical experience and creative non-clinical programmes as well as integrating interprofessional approaches into the modules.