Chronic suppurative otitis media is defined as chronic inflammation of the middle ear and mastoid cavity which present with recurrent ear discharge or otorrhoea through a tympanic membrane perforation [1].

It is an important cause of preventable hearing loss, particularly in the developing world and is a major cause of acquired hearing impairment in children, especially in the developing countries. The prevalence of CSOM is relatively high in rural areas of developing countries, though it is relatively rare in developed countries [2]. Incidence of CSOM varies from 0.5%–2% in developed countries whereas in developing countries it varies from 3%–57%. In India, incidence of CSOM is up to 30% with prevalence rate of 16 and 46 per 1,000 populations respectively in urban and rural areas [3].

A number of histopathological changes can develop in the middle ear and mastoid in CSOM. Some changes are the result of infection and inflammation, while others represent the host response to the disease process. Taken together these changes lead to the signs and symptoms of CSOM and also play an important role in determining success or failure of tympanomastoidectomy for CSOM.

This study highlights the importance of considering histopathological changes in CSOM to improve clinician’s diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities by enabling more rational decisions regarding selection of cases and surgical techniques to optimize control of disease and restoration of hearing. The study also has taken into consideration the microbiological flora causing CSOM.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective study done on the patients of CSOM in the Department of ENT, GSL Medical College and General Hospital, Andhra Pradesh, India, November 2011 to November 2013, after obtaining a study approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Patients of CSOM who attended OPD in the Department of ENT, GSL Medical College and General Hospital and admitted in the ward were taken up for the study after obtaining an informed and written consent from them, regarding their willingness to participate in the study for six months.

Patients who did not attend follow up OPD were excluded from the study.

The condition of CSOM was diagnosed after eliciting proper history, clinical examination and after obtaining the relevant special investigations (microscopic examination, pure tone audiogram, X-ray mastoids, and HRCT temporal bone, CT scan brain if necessary). Mucosa of middle ear was obtained from all such cases and sent for histopathological examination. Mucosa was obtained in the OPD for patients not fit for surgery and those not willing for surgery. In safe CSOM cases, biopsy was taken from only one site during myringoplasty/tympanoplasty through perforation under local anaesthesia under operating microscope or material received at polypectomy. In unsafe CSOM cases, biopsy was taken during mastoid exploration from attic, aditus, antrum and mesotympanum or during polypectomy.

For patients not undergoing surgery, the medical management included aural toilet, local antibiotics and steroid drops, systemic antibiotics and antihistamines. Patients were advised to avoid water entry into ear.

Predisposing factors, if any like deviated nasal septum, adenotonsillitis, sinusitis were addressed first and then the patients were taken up for study. Ossicular chain status was assessed either by preoperative pure tone audiometry or intraoperatively by checking ossicular chain continuity.

The surgical patients were followed up every week for three weeks, fortnightly for the next month and monthly for the next six months. During their postoperative visits, the patients were examined for any aural discharge and hearing assessment and the condition of the graft were assessed after a month.

Results

This study was concerned with the relationship between clinical aspects of CSOM and their relationship with the various pathological features.

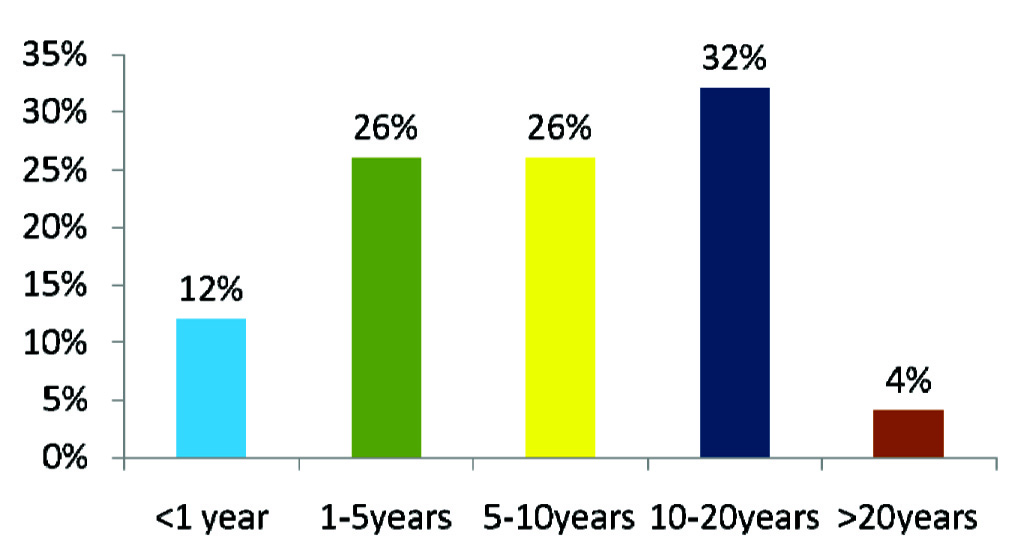

Of the total 50 patients who participated in the study, 26 (52%) were females and 24 (48%) were males. Age distribution of the patients as well as duration of disease is tabulated in [Table/Fig-1,2].

Distribution of patients as per age and sex.

| Age distribution | No. of male patients (%) | No. of female patients (%) |

|---|

| 11-20 years | 9 (18%) | 8 (16%) |

| 21-30 years | 9 (18%) | 8 (16%) |

| 31-40 years | 4 (8%) | 8 (16%) |

| Above 40 years | 2 (4%) | 2 (4%) |

Distribution of cases as per duration of disease.

Based on history and clinical findings, 44 (88%) cases were tubotympanic type of CSOM and 6 (12%) cases were of atticoantral type.

The patients presented with varied clinical symptoms ranging from different types of ear discharge (49 patients) and hearing loss (38 patients) to tinnitus (18 in number) and vertigo (two patients).

History of mucopurulent discharge was present in 30 patients (60%), mucoid discharge in 15 (30%) and blood stained discharge in five patients (10%).

Clinical examination with otoscope revealed a congested (26 patients) and healthy (21 patients) middle ear mucosa with central perforation in a majority of cases though cholesteatoma (five patients-10%) and granulations and polypoidal changes (eight patients-16%) were found occasionally.

Large central perforation was found in 25 patients and 11 patients showed a subtotal perforation. Small central and attic perforations were found in eight and five patients respectively. However, one patient did not show any type of perforation; hence, was excluded.

Microbiologically on obtaining swab and culture of the ear discharge, Staphylococcus aureus was isolated in 20 (40%) cases, coagulase negative Staphylococcus was seen in 8 (16%) cases, Pseudomonas was isolated in 11 (22%) cases, Klebsiella was seen in 9 (18%) cases, Escherichia coli was seen in 2 (4%) cases.

Audiometric evaluation was done by pure tone audiometry, which showed a conductive hearing loss, in almost all the cases with mild to moderate degree hearing impairment, depending on size of perforation, in a vast number of patients in the study [Table/Fig-3].

Degree of hearing loss depending on size of perforation.

| Type of perforation | No. of cases (%) | Range of hearing loss |

|---|

| Subtotal | 11 (22) | 40-56 dB |

| Large central | 25 (50) | 30-48 dB |

| Small central | 08 (16) | 28-30 dB |

| Attic | 05 (10) | 48-76 dB |

After thorough examination and relevant investigations, patients who did not respond to medical treatment were taken up for appropriate surgery, based on the findings. Intraoperatively, necrosed ossicular chain was seen in 11(22%) cases, congested and oedematous mucosa in 32(64%) of patients, cholesteatoma and granulations were found in 5(10%) and 23(46%) of cases respectively. Intact ossicular chain was the most common finding (39 patients-78%).

Depending on the clinical scenario, operative techniques ranged from tympanoplasty to a Modified Radical Mastoidectomy (MRM) [Table/Fig-4]. The histopathological findings are enlisted in [Table/Fig-5].

Types of procedures performed.

| Operative procedure | No. of patients (%) |

|---|

| Tympanoplasty | 27 (54) |

| Canal wall up and typeI tympanoplasty | 13 (26) |

| Canal wall up and type III tympanoplasty | 3 (6) |

| Canal wall up and cartilage interpose | 1 (2) |

| MRM and type III tympanoplasty | 6 (12) |

Histopathological changes among the patients.

| Types of histopathological findings | No. of cases |

|---|

| Non-Keratinised squamous epithelium | 16 (32) |

| Keratinised squamous epithelium | 03 (6) |

| Respiratory epithelium | 03 (6) |

| Cuboidal cells | 10 (20) |

| Low columnar cells | 03(6) |

| Granulation tissue | 17 (34) |

| Lymphocytes | 45 (90) |

| Plasma cells | 44 (88) |

| Histiocytes | 24 (48) |

| Neutrophils | 14 (28) |

| Macrophages | 03 (6) |

| Fibrocollagenous tissue | 26 (52) |

| Eosinophils | 10 (20) |

| Oedematous submucosa | 05 (10) |

| Polypoidal changes in mucosa | 01 (2) |

| Cystic changes | 07 (14) |

| Chronic mastoiditis | 10 (20) |

| Chronic nonspecific inflammation | 14 (28) |

| No opinion possible | 03(6) |

Discussion

This study of 50 patients highlights the importance of clinical features of CSOM and its relationship with various pathological features.

Majority of patients were in the age group of 11-30 years with slightly higher incidence of female sex. This correlates with the study conducted by Varshney S et al., [4]. The early presentation may be due to increased awareness to the health issues and difficulty in hearing affecting work efficiency leading patients and parents to seek early medical intervention. Other studies like that of Wang HM et al., also report the same age incidence [5]. In the study by Lasisi AO and Afolabi OA concluded that probable poor socioeconomic status, overcrowding in the residing places and close contact with the children having upper respiratory tract infection and higher incidence of CSOM during pregnancy could be the reasons for higher female preponderance [6]. Duration of the disease at presentation in OPD correlated with the study by El-Sayed Y [7].

Otorrhoea, followed by hearing loss, were the most common complaints of the patients with CSOM. These features correlated with a study done by Kumar N et al., [8]. Hearing impairment was the second most common clinical feature. Degree of hearing loss correlated with the size of the perforation. Studies by Merchant SN and Rosowski JJ and Ahmed SW and Ramani GV have reported that air bone gap is positively correlated with the size of the perforation [9,10].

Central perforation was the most common finding which correlated with a study by Nagle SK et al., which found small central perforation in 20% of cases, large central perforation in 23% of cases and medium sized perforation in 57% of patients [11]. Regarding otoscopic findings, healthy middle ear mucosa was observed in 21 cases i.e., 42% almost same as the study by Krishnan A et al., [12]. Microbiological findings were similar to a study by Prakash R et al., where Staphylococcus aureus was isolated in 48.69% of cases and Pseudomonas in 19.89% of cases [13].

Intraoperatively, intact ossicular chain was seen in 39 cases i.e., 78%, ossicular necrosis was seen in 11(22%) cases, which is almost in accordance with a study by Haidar H et al., [14].

Out of the 11 cases, long process of incus was found necrosed in 10 cases, similar to a study conducted by Rout MR et al., which showed that the long process of incus was the most common ossicle to get necrosed, malleus was necrosed in seven cases and stapes superstructure necrosis seen in two cases [15]. Malleus necrosis was accompanied with incus necrosis.

Intraoperatively cholesteatoma was seen in 5 (10%) cases, granulations were seen in mastoid antrum in 23 (46%) cases. In these cases, middle ear mucosa was persistently congested, not responding to topical and systemic antibiotics, thus reflecting the fact that middle ear pathology reflects the antral pathology. In a study by Rickers J et al., granulations were seen in 57% of cases [16].

Effect of medical management i.e., topical and systemic antibiotics on 24 cases of tubotympanic type of CSOM with active middle ear mucosa showed improvement in eight cases by decrease in congestion and while remaining 16 cases did not respond to medical treatment.

On histopathological examination, majority of cases showed changes corresponding to changes of chronic inflammation with the presence of lymphoplasmacytic infiltration in majority of cases, granulation tissue in 17 cases.

As far as the ossicular chain status was concerned, it was found that ossicular necrosis was seen in 11 (22%) cases. Out of these 11 cases, incus was necrosed in 10 cases, malleus was necrosed in seven cases. Malleus necrosis accompanied incus necrosis. Stapes superstructure was seen in two cases. So in this study, incus was the most commonly necrosed ossicle followed by malleus and then stapes. Tos M in his study found that incus and stapes were more frequently necrosed ossicles [17]. He studied 674 cases out of which only 56 (8.3%) had necrosis of long process of incus. The body of incus was eroded in only two cases and stapes superstructure in 15 cases. Sade J et al., found that malleus and incus could be equally affected [18].

In our study, presence of granulation tissue was associated with ossicular necrosis in 47.5% of cases. This was found to be important. This correlates with literature which states that middle ear granulations are known to cause ossicular resorption. Chole RA and Choo MJ found that when perforation edges adhere to the promontory [19], it confines the granulation tissue and inflammatory products in small dead spaces of the middle ear cleft which could lead to significant bone erosion over a period of time. Other studies have also proved that granulation tissue could be significantly associated with ossicular necrosis.

Mean PTA threshold in 11 cases of ossicular necrosis was 54.36 dB. According to literature, Air Bone Gap (ABG) greater than 30 dB at 2kHz and greater than 40 dB at 4kHz increased the probability of ossicular discontinuity [20]. According to literature, raised PTA average threshold of 41-70 dB is significantly associated with incus necrosis [21].

Regarding surgical intervention, out of 50 cases, tympanoplasty was done in 27 cases of tubotympanic CSOM. Regarding the success of graft take up postoperatively, it was noticed that 46 cases (92%) had successful take up of the graft and 4 cases (8%) had graft failure. The success rate of graft take up almost correlated with the study done by Kamath MP et al., [22]. Regarding postoperative hearing levels, hearing gain was noticed in about 80% of cases as shown by postoperative PTA reports.

Out of 24 cases of tubotympanic CSOM having active middle ear mucosa, 8 cases responded to medical treatment in the form of decreased congestion of middle ear mucosa. These 8 cases underwent tympanoplasty whereas remaining 16 cases underwent Canal Wall Up mastoidectomy and tympanoplasty which revealed granulations in mastoid antrum as indicated by preoperative X-ray mastoids showing sclerosis, thus emphasizing the fact that middle ear pathology reflects pathology in mastoid antrum.

Conclusion

The present study lays emphasis on comprehensive management of CSOM taking into account the various clinical and pathological features. Congested middle ear mucosa on otoscopic examination correlated with intraoperative mastoid granulations in around 60-70% of cases, reflecting the fact that middle ear pathology reflects mastoid antrum pathology. Ossicular necrosis was seen in all the cases of cholesteatoma and in 47.8% of cases with granulation tissue highlighting the importance of planning an additional tympanoplasty procedure when cholesteatoma or granulation tissue is observed pre/intraoperatively. Careful clinical examination, like assessing the size and type of perforation, stage of CSOM, condition of middle ear mucosa etc and relevant investigations like pure tone audiometry, will help us in planning the appropriate operative procedures and to bring better outcome to the patients.