High school student are adolescents between 15 and 19 years of ages, mostly they study very hard for the national entrance examination into college or university. Therefore, educational stress is a common emotional state among school children and adolescents worldwide and appears to be more severe among Asians [1–3]. Inability of adolescents to cope with the stress properly could result in mental ill health. Mental health problems have influences on both physical health and QOL of high school students in Asia, such as Japan, Korean, China, Vietnam, Singapore and Thailand [4–8].

Previous studies reported that about 19-42% Thai adolescents who studied in grades 10th, 11th and 12th had experienced depression [9,10], anxiety disorder (11%) and specific phobias (10%) [11]. Many factors contribute to poor mental health, such as learning or educational problems, family conflict and drug abuse. Thai students spend a lot of time in classroom and many extra hours after school for tutorial classes that can cause stress and adverse impact on the health status since students focus on academic excellent outcomes [8,12,13]. Most students who finish high school aim to study at a university. They are more likely to have higher level of stress especially during the period of admission examinations which results in high incidents of mental ill-heath [1,14]. Previous studies reported that learning, thinking and reasoning system, self-expectation, parental expectations and peer relationships had influence on mental ill-health and QOL of high school students in both short and long terms [2,15,16].

A study on academic stress among students indicated that there was lack of precision in terminology of the term “stress”, in some studies done on academic stress [8,17,18]. Several investigators have focused on stressful life events related to stressors or subjective stress [6,19]. Although these studies can notice the most prevalent and significant stressors, they may not examine the real stress of high school students. In Thailand as well as the Northeast region, both in term of land area and population, there is a lack of research specifically concerned with educational stress, mental health and their relationship with the QOL of high school students.

This study aimed to identify the prevalence of mental health problems, educational stress, other possible risk factors and QOL perceived by Thai adolescents, attending high school and to examine their relationships with high level of QOL. The results of this study may be an evidence for both health and educational sectors to develop appropriate measures to reduce educational stress and improve QOL of high school students.

Materials and Methods

The present cross-sectional study was conducted during May 2013 to August 2013 in 5 high schools of the Northeast of Thailand. The sample size was estimated using a generalized linear mixed (logistic regression) model (GLMM) formula of which 1,112 subjects were identified [20]. This study applied a multistage random sampling method to select the samples. The sampling frame was, all 15 Secondary Educational Service Area Office (SESAO) in the Northeast of Thailand. The first stage was random selection of 5 SESAO, followed by random selection of 5 provinces from 5 SESAO, then one high school which is located in the city center of each province was randomly selected, therefore 5 schools were included in the study. The fourth stage involved a stratified random sampling of 556 male and 556 female high school students, proportional to the number of the high school students in those 5 schools. The process involved a name list of all students of each high school class (grades 10th, 11th, and 12th) which was sorted by gender. Then systematic random sampling was applied to select male and female high school students in proportion to the size of the estimated total sample. A total of 5 high schools and 1,112 students were chosen to be involved in this study.

The inclusion criterion for participants was: students in high school (grades 10th, 11th and 12th) in Northeastern of Thailand. Students agreed and signed the written consent form, if they were younger than 18 years old, their parents were asked to sign the consent form. Exclusion criterion was: students who were studying in vocational school, college and informal education sectors.

Research Instruments

The research instrument in this study was a structured questionnaire which consisted of six sections: (1) Demographic and socioeconomic; (2) Stress of high school student; (3) Anxiety; (4) Depression; (5) General well-being; and (6) Quality of Life.

Demographic and socioeconomic questions consisted of sex, age, school year, study program, student educational performance (grade point average: GPA), congenital disease, alcohol drinking and smoking.

Educational stress of high school students was assessed by using the Educational Stress Scale for Adolescents (ESSA). The ESSA contains five domains, including pressure from study, worry about grades, self-expectation stress, workload, and study despondency with a total of 16 items, and using 5 point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The educational stress are classified into 3 groups: high level (> 58 scores), moderate level (51-58 scores) and low level (< 50 scores) [21]. The ESSA was firstly developed and tested in China [19]. This instrument has an adequate internal consistency with the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient = 0.82 for the total scale, and α = 0.79, α = 0.73, α = 0.69, α = 0.65, and α = 0.64 for the five factors, respectively. This study applied the English version of ESSA questionnaire and translated it into Thai using forward and backward translation procedures. We adjusted some terms to fit Thai context such as ‘academic grade’ in ESSA was replaced with ‘Grade Point Average (GPA)’ in this study. The tool was tested for content validity by 7 experts and a pilot study with 30 high school students in Northeast of Thailand, who were not sampled in the main study, for reliability. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient = 0.83 for the total scale, and α = 0.78, α = 0.75, α = 0.71, α = 0.66, and α = 0.72 for the five factors, respectively.

This study used the Thai Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale to assess the level of anxiety in high school students in Thailand. The Thai Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Thai HADS) is composed of 14 items with 4 points ranging from 0 (none of the time) to 3 (very often) [22]. The anxiety domain composed of 7 items (all odd numbers) and the depression domain composed of 7 items (all even numbers), the cut off point was more than 11 points. It had Cronbach’s alpha coefficient=0.85, sensitivity=100%, specificity=86.0%. Concerning the anxiety sub scale and depression sub scale, their Cronbach’s alpha coefficient = 0.82, sensitivity = 85.70%, specificity = 91.30%.

For depression screening, the study used the Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D). The CES-D Thai version was developed by Tragkasombat et al., [23]. The CES-D Thai version consists of twenty questions with 4 point scales ranging from 0 (none) to 3 (very often). The cut off points were; 0-22 scores is normal, >22 scores is having depression. Its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.86, sensitivity = 72.00%, specificity = 85.00%, accuracy = 82.00% for depression screening.

General well-being was determined using the WHO-5 Well-being Index Thai version [24]. This scale consists of five items, covering positive mood, vitality, and general interest over the last 2 weeks. The 6 point rating scale ranges from 0 = at no time to 5 = all of the time. Responses were averaged across the five items; high scores indicate greater happiness. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.80 for the total scale.

Quality of life was determined using the World Health Organization Quality of Life scale (WHOQOL – BREF – THAI) [25]. Thai short version has 26 items with 4 domains namely physical, psychological, social relationships and environment domain. The scores of the short version are divided into 3 groups: good level (96-130 scores), fair level (61-95 scores) and poor level (26-60 scores). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient = 0.84 for the total scale.

Seven experts were invited to review the questionnaires and the revisions were made to improve their validity. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, of which this questionnaire had high reliability, α = 0.86.

The students in the study were asked to complete a self-administered questionnaire in the absence of their teachers in the classroom. The researchers were in the classrooms before the students started filling the questionnaire to answer any possible question which may be raised by the students and assisted them if necessary. The subjects were sitting at least 1 meter apart from each other to ensure privacy. The completed questionnaires were placed into the individual envelopes, sealed and put into a box to ensure their total anonymity. If students were tired and felt uncomfortable in completing the questionnaires, they could stop, take a break, or could ask for individual counseling from the researcher. A free counseling service was offered to any student who may experience some distress during participation in the research. Data collection was carefully conducted to protect the child rights.

The research proposal as well as the tools were submitted and approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Khon Kaen University (reference no. HE571132).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using the statistical package of Stata version 10.0 [26]. Frequency and percentage were used to present the categorical variables. Continuous variables were described as mean and standard deviation, median and range (minimum: maximum).

Association of mental health, educational stress, and QOL of high school students was the primary outcome to be quantified. Since the study used multistage random sampling methods for data collection, generalized linear mixed (logistic regression) model (GLMM) were performed to model the random effects and correlations within clusters [27]. The area, in which schools were located and classes in each school, were set as the random effect. Univariate analysis was done to explore the magnitude of QOL, presented as prevalence of good QOL together with its 95% Confidence Interval (CI). Bivariate analysis was used to determine the association of each independent variable such as mental health, educational stress with QOL. In our analysis, any independent variable that had p<0.25 was selected and proceeded to the multivariable analysis. However, some variables that have been identified by previous studies that they had influence on the independent variable (QOL) also have to be included in the multivariable analysis, even though the p-value was ≥0.25, otherwise they would behave as the “confounders” and might interfere with the result. In this study the association between “age” with good quality of life had p-value = 0.263 and “school year” had p-value of 0.744 [6,7,9,16,28], were included in the multivariable analysis. The multiple logistic regressions were performed to identify the association between mental health, educational stress and QOL while controlling covariates (sex, age, and school years). The final model results were presented as adjusted odds ratio (adjusted OR), 95% CI, and the levels of significance at 0.05.

Results

The sample was taken from high school students that consisted of equal number of males and females. The average age was 16.35 ± 0.94 years old. The representation of students was almost equal among each grade from 10th to 12th i.e., about 33% (grade 10th: 32.37%, grade 11th: 33.27% and grade 12th: 34.35%). More than half were studying in the mathematics and science program. Their Grade Point Average (GPA) was 3.18 ± 0.48. Most of them had no chronic health problems/diseases. Majority did not drink alcohol. In addition most of them were not smokers [Table/Fig-1].

Characteristics of the sampled high school students (n= 1,112).

| Characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|

| Sex |

| Female | 556(50.00) |

| Male | 556(50.00) |

| Age (years) |

| 15 or lower | 222(19.96) |

| 16 | 394(35.43) |

| 17 or greater | 496(44.60) |

| Mean±SD: 16.35 ± 0.94 years, Median (Min, Max): 16 (14,19) | |

| School years |

| Grade 10 | 360(32.37) |

| Grade 11 | 370(33.27) |

| Grade 12 | 382(34.35) |

| Study Program |

| Mathematics-Science | 776(69.78) |

| English-Chinese | 142(12.77) |

| Mathematics-English | 94(8.45) |

| Art-Language | 65(5.85) |

| English-Japanese | 35(3.15) |

| Grade Point Average (GPA) |

| 2.00 or lower | 25(2.25) |

| 2.00–3.00 | 416(37.41) |

| 3.00 or greater | 671(60.34) |

| Mean±SD: 3.18 ± 0.48, Median (Min, Max): 3.19 (1,4) | |

| Congenital disease |

| No | 932(83.81) |

| Yes | 180(16.19) |

| Alcohol drinking |

| No | 707(63.58) |

| Yes, occasional drinker and socialize or festival | 308(27.70) |

| Current not drinker | 55(4.95) |

| Current drinker | 42(3.78) |

| Smoking |

| No | 1,016(91.37) |

| Current not smoker | 69(6.21) |

| Current smoker | 27(2.43) |

| Quality of life |

| Good (96-130 Scores) | 406(36.51) |

| Moderate (61–95 Scores) | 692(62.23) |

| Poor (26–60Scores) | 14(1.26) |

| Mean±SD: 91.52±13.54, Median (Min, Max): 91 (48, 130), Total 130 scores. |

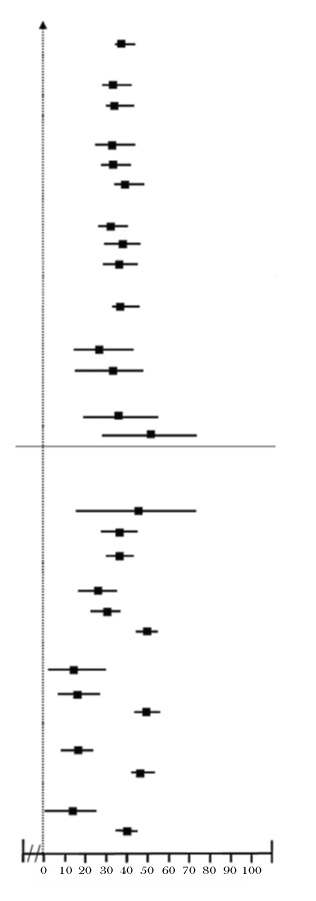

The prevalence of good QOL was 36.51% (95% CI: 32.30 to 41.69), 26.18% (95% CI: 16.72 to 35.63) had high level of educational stress, and 16.41 % (2.20 to 30.71) had high level of anxiety. As high as 18.55% (95% CI: 9.86 to 27.23) of the students had depression. However, most of the high school students had high level of general well-being 40.90% (95% CI: 35.96 to 45.83) [Table/Fig-2].

Prevalence of good quality of life of high school students (n=1,112), *95% CI: 95% confident interval.

| Parameters | Number | Prevalence | 95% CI* |

|---|

| Good QOL (%) | Forest plot |

|---|

| Overall | 1,112 | 36.51 |  | 32.30 to 41.69 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 556 | 34.35 | 27.61 to 41.08 |

| Male | 556 | 38.67 | 31.82 to 41.19 |

| Age (years) | |

| 15 or lower | 222 | 34.23 | 23.56 to 44.89 |

| 16 | 394 | 34.26 | 26.25 to 42.26 |

| 17 or greater | 496 | 39.31 | 32.45 to 46.16 |

| School years | |

| Grade10th | 360 | 35.00 | 26.67 to 43.32 |

| Grade11th | 370 | 37.57 | 29.51 to 45.62 |

| Grade12th | 382 | 36.91 | 28.94 to 44.87 |

| Study Program | |

| Mathematics – Science | 776 | 37.37 | 31.80 to 42.93 |

| English - Chinese | 142 | 29.58 | 15.77 to 43.38 |

| Mathematics – English | 94 | 32.39 | 16.43 to 49.52 |

| Art-Language | 65 | 38.46 | 19.38 to 57.53 |

| English-Japanese | 35 | 51.43 | 28.34 to 74.51 |

| Grade Point Average (GPA) | |

| 2.00 or lower | 25 | 44.00 | 14.66 to 73.33 |

| 2.00 – 3.00 | 416 | 36.54 | 28.88 to 44.19 |

| 3.00 or greater | 671 | 36.21 | 30.16 to 42.25 |

| Educational stress | |

| High | 317 | 26.18 | 16.72 to 35.63 |

| Moderate | 372 | 29.84 | 21.32 to 38.35 |

| Low | 423 | 50.12 | 43.38 to 56.85 |

| Anxiety | |

| High | 158 | 16.41 | 2.20 to 30.71 |

| Moderate | 278 | 18.71 | 8.11 to 29.30 |

| Low | 676 | 48.52 | 43.11 to 53.92 |

| Depression | |

| Depression | 415 | 18.55 | 9.86 to 27.23 |

| Normal | 697 | 47.20 | 41.80 to 52.59 |

| General well-being | |

| Low | 178 | 13.41 | 0.18 to 27.14 |

| High | 934 | 40.90 | 35.96 to 45.83 |

The bivariate analysis by applying the Backward Wald method indicated that having moderate to low levels of educational stress (OR=1.92; 95% CI: 1.44 to 2.56; p<0.001), moderate and low levels of anxiety (OR=3.36; 95% CI: 2.16 to 5.21; p< 0.001), did not have depression (OR=3.92; 95% CI: 2.94 to 5.23; p<0.001) and had high level of general well-being (OR= 4.44; 95% CI: 2.83 to 6.96; p<0.001) were significantly associated with the high school students’ QOL. [Table/Fig-3].

Bivariate analysis for factors associated with good quality of life (n=1,112), *OR: odds ratio; **95% CI: 95% confident interval; p-value < 0.25 selected formultivariate analysis.

| Factors | Number | Good QOL (%) | Crude OR* | 95%CI** | p-value |

|---|

| Sex | 0.133 |

| Female | 556 | 34.35 | 1 | |

| Male | 556 | 38.67 | 1.20 | 0.94 to 1.54 |

| Age(Years) | 0.263 |

| 15 or lower | 222 | 34.23 | 1 | |

| 16 | 394 | 34.26 | 0.99 | 0.69 to 1.41 |

| 17 or greater | 496 | 39.31 | 1.23 | 0.88 to 1.73 |

| School years | 0.744 |

| Grade10th | 360 | 35.00 | 1 | |

| Grade11th | 370 | 37.57 | 1.11 | 0.82 to 1.51 |

| Grade12th | 382 | 36.91 | 1.10 | 0.81 to 1.49 |

| Study Program | 0.414 |

| Mathematics - Science | 776 | 37.37 | 1 | |

| Mathematics – English | 94 | 32.39 | 0.84 | 0.52 to 1.34 |

| English - Chinese | 142 | 29.58 | 0.85 | 0.55 to 1.33 |

| English- Japanese | 35 | 51.43 | 1.71 | 0.85 to 3.42 |

| Art-Language | 65 | 38.46 | 1.16 | 0.67 to 2.01 |

| Grade Point Average (GPA) | 0.681 |

| 2.00 or lower | 25 | 44.00 | 1 | |

| 2.00 – 3.00 | 416 | 36.54 | 0.70 | 0.31 to 1.61 |

| 3.00 or greater | 671 | 36.21 | 0.74 | 0.33 to 1.69 |

| Congenital disease | 0.253 |

| Yes | 180 | 32.78 | 1 | |

| No | 932 | 37.23 | 1.21 | 0.86 to 1.70 |

| Alcohol drinking | 0.071 |

| Yes | 405 | 33.09 | 1 | |

| No | 707 | 38.47 | 1.26 | 0.97 to 1.63 |

| Smoking | 0.833 |

| Yes | 96 | 37.50 | 1 | |

| No | 1,016 | 36.42 | 0.95 | 0.62 to 1.47 |

| Educational stress | <0.001 |

| High | 317 | 26.18 | 1 | |

| Low/Moderate | 795 | 40.63 | 1.92 | 1.44 to 2.56 |

| Anxiety | <0.001 |

| High | 158 | 16.46 | 1 | |

| Low/Moderate | 954 | 39.83 | 3.36 | 2.16 to 5.21 |

| Depression | <0.001 |

| Depression | 415 | 18.55 | 1 | |

| Normal | 697 | 47.20 | 3.92 | 2.94 to 5.23 |

| General well-being | <0.001 |

| Low | 178 | 13.41 | 1 | |

| High | 934 | 40.90 | 4.44 | 2.83 to 6.96 |

The final model from multivariate analysis that being controlled the clustering effect by GLMM and controlled covariates (sex, age and school years) indicated that factors which were significantly associated with good QOL had low to moderate of anxiety (OR=1.60; 95% CI:1.01 to 2.67), did not have depression (OR=3.07; 95% CI: 2.23 to 4.22; p<0.001) and had high level of general well-being (OR=3.19; 95%CI:1.99 to 5.09; p<0.001) [Table/Fig-4].

Multivariate analysis for factors associated with good quality of life (n=1,112), *OR: odds ratio; **95% CI: 95% confident interval, p-value < 0.05 is considered as significant.

| Factors | Number | Good QOL (%) | Crude OR* (95%CI**) | Adjusted OR* (95%CI**) | p-value |

|---|

| Sex | 0.259 |

| Female | 556 | 34.35 | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 556 | 38.67 | 1.20(0.94 to 1.54) | 1.16(0.89 to 1.50) |

| Age(Years) | 0.524 |

| ≤15 | 222 | 34.23 | 1 | 1 |

| 16 | 394 | 34.26 | 0.99(0.69 to 1.41) | 1.16(0.73 to 1.84) |

| ≥17 | 496 | 39.31 | 1.23(0.88 to 1.73) | 1.79(0.97 to 3.33) |

| School years | 0.330 |

| Grade10th | 360 | 35.00 | 1 | 1 |

| Grade11th | 370 | 37.57 | 1.11(0.82 to 1.51) | 0.80(0.51 to 1.25) |

| Grade12th | 382 | 36.91 | 1.10(0.81 to 1.49) | 0.55(0.30 to 0.99) |

| Educational stress | 0.533 |

| High | 317 | 26.18 | 1 | 1 |

| Low/Moderate | 795 | 40.63 | 1.92(1.44 to 2.56) | 1.11(0.79 to 1.54) |

| Anxiety | 0.045 |

| High | 158 | 16.46 | 1 | 1 |

| Low/Moderate | 954 | 39.83 | 3.36(2.16 to 5.21) | 1.60(1.01 to 2.67) |

| Depression | <0.001 |

| Depression | 415 | 18.55 | 1 | 1 |

| Normal | 697 | 47.20 | 3.92(2.94 to 5.23) | 3.07(2.23 to 4.22) |

| General well-being | <0.001 |

| Low | 178 | 13.41 | 1 | 1 |

| High | 934 | 40.90 | 4.44 (2.83 to 6.96) | 3.19(1.99 to 5.09) |

Discussion

About 26% of high school students in this study had high level of educational stress. Educational stress has been identified as a significant contributor to a variety of mental and behavioural disorders of students [6, 28, 29]. Stress is major risk factor for depression, and suicide of which, is the thirst leading cause of mortality among the 15-24 year of age group [9,16]. The results of this research also found that 16.41% of the students had high level of anxiety. It was higher than 4.10% found in China [6]. However, it was lower than the anxiety prevalence among adolescents that was approximately 8-12% and much lower than that of high school students in Vietnam (22.80%) [28]. The high prevalence of anxiety might be from influences of various pressures on students since anxiety is associated with substantial negative influences on children’s social, emotional and academic success [28,30].

The prevalence of depression was as high as 18.55% in this study, similar to the prevalence of depression among Thai adolescents that ranged between 15% and 30% [31]. Depression was a major problem of adolescents in Asia, such as China, Singapore, Vietnam and Japan [6,7,28,32]. This study revealed a very significant finding since depression is a combination of symptoms in terms of change in mood, physical symptoms like changes in sleep, energy and appetite, and also a person’s degree of confidence. Depression is linked to increased risk of substance abuse, unemployment, early pregnancy and educational under achievement which has an impact on students both in short and long term.

About 40% of the high school students had high level of well-being; whereas, it was only 20% in Vietnam [21]. General well-being means that people are healthy, which comprehensively covers physical, psychological and social aspects of health, family conditions, socioeconomic situation, and being with others. If adolescents have high level of well-being, they are more likely to have successful life in future [33]. It was supported by a study among adolescent students in Cartagena, Colombia which found that high self-esteem, intense religiousness and having a functional family could together predict their well-being [34].

Even though 40.90% of the high school students had high level of well-being, only 36.51% had good QOL, followed by 62.23% with moderate and 1.26 % with poor QOL. Previous study indicated that high school students in Thailand had moderate level of QOL [8]. Factors associated with QOL were; no depression (OR=3.07; 95% CI: 2.23 to 4.22; p<0.001) and had high level of general well-being (OR=3.19; 95% CI: 1.99 to 5.09; p<0.001). It could be explained that since depression is a combination of symptoms of change in mood, sleep, energy and appetite, and also a person’s degree of confidence and linked to increased risks of substance abuse, unemployment, early pregnancy and educational under achievement, those with depression would have poorer wellbeing and QOL. This finding was similar with other studies from Thailand, which indicated that QOL is associated with well-being and not stress, since stress affects the health of people [25,31]. Therefore, if we could improve or control the factors associated with QOL, student’s well-being will improve.

Limitation

The nature of cross-sectional design, both the independent variables and dependent variables were identified at the same time, are limitations of the study, in drawing the causal relationship between educational stress, mental health status and QOL. It is suggested that further future studies should apply longitudinal designs such as prospective cohort or experimental to confirm this causality.

Conclusion

The prevalence of educational stress, anxiety and depression was high and conform with the finding of others studies. The National Entrance Examination for high school students for university admission puts a high pressure educational stress on the students. The high expectations of family, school, and peers cause chronic stress and depression among the students. High level of well-being, less anxiety and depression were found to have strong influence on QOL. The recommendations are: counseling skills development, promoting activities to improve parents understanding of their children; and reduced expectations of parents towards students.

Financial support: Authors thank the Research and Training Centre for Enhancing the Quality of Life of Working Age People (REQW), Khon Kaen University, Thailand for financial support for this research.