Molar pregnancy is one of the components of a broader spectrum of diseases known as Gestational Trophoblastic Disease (GTD), presenting with amenorrhoea and irregular bleeding which may be rarely associated with passage of vesicles per vagina. However, it can rarely be associated with hyperthyroidism, which may be associated with clinical features of hyperthyroidism. The following is a report of a 20-year-old woman who presented with amenorrhea followed by irregular bleeding per vagina, thyromegaly and abnormal levels of thyroid hormones. Transvaginal ultrasound revealed features consistent with molar pregnancy. A suction evacuation was done following which serum levels of β-hCG reduced and the levels of thyroid hormones also reduced. On follow up, six weeks later, β-hCG and thyroid hormones were within normal limits. The case and relevant literature are presented here.

Abdominal distension, Hydatidiform mole, Hyperthyroidism

Case Report

A 20-year-old nulliparous woman, married since one year, presented to the outpatient department with complaints of three months of amenorrhea followed by increased bleeding per vagina, hyperemesis and abdominal pain of one week duration. She also complained of tremors and palpitation. There was no history of abdominal distension or diarrhoea. There was no history of menstrual irregularity prior to the current episode.

On examination, her pulse rate was 110 beats per minute and regular in rhythm, blood pressure was 120/78 mmHg, respiratory rate was 16 breaths per minute and oxygen saturation was 99% at room air. She was found to have conjunctival pallor and diffuse non tender enlargement of the thyroid gland. On abdominal examination, there was no palpable mass present. On per vaginal examination, the uterus was found to be bulky (about 10 weeks of gestational size), anteverted, with mild cervical motion tenderness present. Bilateral fornices were free and non tender. Urine pregnancy test was found to be positive. Transvaginal ultrasound of pelvis revealed uterus which measured 10.6x7 cm, with intrauterine gestational sac measuring 4.3 cm and presence of anechoic areas likely to be cystic, suggestive of molar pregnancy. Bilateral ovaries on ultrasound showed theca lutein cysts with the largest measuring 18 mm. Laboratory data showed β-hCG levels of 8,04,578 mIU/ml, haemoglobin of 8.4 g/dl, peripheral smear showed microcytic hypochromic picture, TSH levels of 0.015 mIU/ml, T3 of 3.07 ng/ml and T4 of 24.86 μg/dl. Thyroid profile was done after seeking consultation with physician for tremors and palpitation. Ultrasound of the thyroid gland showed diffuse enlargement of the gland without nodularity and Technetium-99m scan of thyroid was done which was found to be normal. Electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia and 2D-ECHO was normal.

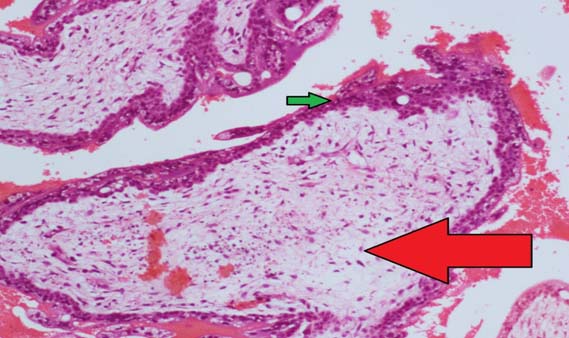

She was subsequently admitted and transfused 2 units of packed red blood cells and was started on propranolol (60 mg/day). An ultrasound guided suction evacuation of products of conception was done under general anaesthesia three days following admission. Histopathology report of specimen confirmed diagnosis of hydatidiform mole [Table/Fig-1]. A repeat ultrasound scan done following evacuation showed retained products of conception and laboratory data showed β-hCG of 89,677 mIU/ml, TSH of 0.015 mIU/ml,T3 of 1.37 ng/ml and T4 of 17.47 μg/dl. She was discharged with the instruction not to conceive for the next six months. The patient was advised to come weekly for β-hCG levels which showed progressive decline. At six weeks following evacuation, her β-hCG was found to be 17.6 mIU/ml and thyroid parameters were normal (TSH of 1.82 mIU/ml, T3 of 1.08 ng/ml and T4 of 7.86 μg/dl). Propranolol was stopped at this visit.

H&E, 100X image showing cystic dilated chorionic villi (red arrow) with trophoblasts (green arrow).

Discussion

Our patient had features of molar pregnancy at presentation with hyperthyroidism which was controlled with β-blockers.

GTD is a broad term used to define a spectrum, comprising of hydatidiform mole (complete or partial), placental site trophoblastic tumour, choriocarcinoma and gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Out of these, the most commonly occurring form is the hydatidiform mole, which is also known as molar pregnancy. Classification of molar pregnancies can be complete or partial on the basis of gross morphology of the specimen, histopathologic features and karyotype [1]. The incidence of molar pregnancy in North America is about 0.1% of all pregnancies; while in Asia, it is upto three times higher [2]. In India, the incidence rate of molar pregnancy is about one in every 400 pregnancies [3].

Molar pregnancy presents with period of amenorrhea lasting a few weeks to months, followed by vaginal bleeding, abdominal mass, hyperemesis and rarely passage of vesicles per vagina, etc. Bleeding per vagina is the usual complaint (84%), which may or may not be associated with menstrual delay, whereas vomiting is present in 28% of cases that can be refractory to treatment. Hyperemesis gravidarum is usually seen in cases of hydatidiform mole that have high hCG levels [4]. Additionally, it is also common for such patients to have theca lutein cysts due to ovarian hyperstimulation as a result of high hCG levels.

Early diagnosis of molar pregnancy can be made by early prenatal care and timely use of ultrasound. This prevents clinical presentations such as huge hydatidiform moles, passage of vesicles per vagina, severe anaemia and emergency situations. Anaemia may be present in women of low socioeconomic status, especially in tropical countries, due to the presence of iron deficiency secondary to worm infestation. Hyperthyroidism is a rare complication of GTD, attributed to the increased levels of β-hCG released by the tumour [5].

The hCG molecule is made of α and β subunits; which have a similarity in structure to the TSH molecule. Since hCG and TSH receptors are similar, hCG acts directly on the TSH receptors that are present in the thyroid resulting in an increased level of thyroid hormones T3 and T4 and decreased TSH levels [5].

The first reported case of hyperthyroidism as a complication of hydatidiform mole was in 1955 [6]. In approximately 67% of the cases, β-hCG levels greater than 2,00,000 mIU/ml have been found to suppress TSH (lower or equal to 0.2 mIU/ml), while levels above 4,00,000 mIU/ml can lead to suppression in upto 100% of cases [7]. Depending on the severity of the trophoblastic disease, the patient may have clinically asymptomatic elevations of thyroid hormones or can have something as severe as thyrotoxicosis [8].

Patients with clinically evident hyperthyroidism can have varying signs and symptoms such as weight loss, easy fatigability, increased sweating, heat intolerance, palpitations, tremors, opthalmopathy and clinically enlarged thyroid gland.

In patients with uncontrolled hyperthyroidism, surgery and anaesthesia are associated with significant perioperative mortality [9]. Due to undetected hyperthyroidism, the patient may develop tachycardia, arrhythmias, hyperthermia and high output cardiac failure and can even progress to a life threatening thyroid storm during the surgery [10]. Hence it is important to check for thyroid levels in every patient of GTD in order to anticipate and be prepared for complications that may arise during surgical procedure for treatment of GTD.

Surgical uterine evacuation is the mainstay of management for hydatidiform mole, either complete or partial mole. Regardless of uterine size, suction curettage is the preferred technique for uterine evacuation [11]. Use of medications like misoprostol and oxytocin for uterine evacuation is controversial [11]. A study that was done where only medication was given as a therapy for hydatidiform mole reported the need of uterine curettage [12]. Levels of β-hCG are usually followed up weekly until the levels reach within normal range for a period of four weeks. β-hCG levels are commonly found to reach normal levels within two to three months of evacuation of the molar pregnancy and intervention is not needed unless there is rise in β-hCG levels [13].

Once levels have reached the reference range for a period of four weeks, they are followed up monthly thereafter for six months to look for evidence of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia by looking for a rise in β-hCG levels [14-16].

Conclusion

A physician should be aware of the possibility of transient hyperthyroidism with molar pregnancy. The thyroid abnormality usually subsides with evacuation of hydatidiform mole and may rarely require treatment with antithyroid drugs. In our patient, only ultrasound guided suction evacuation of products of conception was done to regain euthyroidism without the need for antithyroid drugs.

[1]. Garner EI, Goldstein DP, Feltmate CM, Berkowitz RS, Gestational trophoblastic diseaseClin Obstet Gynecol 2007 50:112-22. [Google Scholar]

[2]. Gerulath AH, Ehlen TG, Bessette P, Jolicoeur L, Savoie R, Gerulath AH, Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada;Gynaecologic Oncologists of Canada;Society of Canadian ColposcopistsJ Obstet Gynaecol Can 2002 24:434-46. [Google Scholar]

[3]. Nandini D, Sarita F, Uday A, Hemalata I, Hydatidiform mole with hyperthyroidism-perioperative challengesJ Obstet Gynecol India 2009 59:356-57. [Google Scholar]

[4]. Soto-Wright V, Bernstein M, Goldstein DP, The changing clinical presentation of complete molar pregnancyObstet Gynecol 1995 86(5):775-79. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Narasimhan KL, Ghobrial MW, Ruby EB, Hyperthyroidism in the setting of gestational trophoblastic diseaseAm J Med Sci 2002 323:285-87. [Google Scholar]

[6]. Hershman JM, Hyperthyroidism induced by trophoblastic thyrotropinMayo Clin Proc 1972 47:913-18. [Google Scholar]

[7]. Erbil Y, Tihan D, Azezli A, Severe hyperthyroidism requiring therapeutic plasmapheresis in a patient with hydatidiform moleGynecol Endocrinol 2006 22:402-04. [Google Scholar]

[8]. Langley RW, Burch HB, Perioperative management of the thyrotoxic patientEndocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2003 32:519-34. [Google Scholar]

[9]. Kim JM, Arakawa K, McCann V, Severe hyperthyroidism associated with hydatidiform moleAnesthesiology 1976 44:445-48. [Google Scholar]

[10]. Adali E, Yildizhan R, Kolusari A, Kurdoglu M, Turan N, The use of plasmapheresis for rapid hormonal control in severe hyperthyroidism caused by a partial molar pregnancyArch Gynecol Obstet 2009 279:569-71. [Google Scholar]

[11]. Berkowitz RS, Goldstein DP, Clinical practice. Molar pregnancyN Engl J Med 2009 360:1639-45. [Google Scholar]

[12]. Tidy JA, Gillespie AM, Bright N, Radstone CR, Coleman RE, Hancock BW, Gestational trophoblastic disease: a study of mode of evacuation and subsequent need for treatment with chemotherapyGynecol Oncol 2000 78:309-12. [Google Scholar]

[13]. Agarwal R, Teoh S, Short D, Harvey R, Savage PM, Seckl MJ, Chemotherapy and human chorionic gonadotropin concentrations 6 months after uterine evacuation of molar pregnancy: a retrospective cohort studyLancet 2012 379(9811):130-35. [Google Scholar]

[14]. Sebire NJ, Foskett M, Short D, Savage P, Stewart W, Thomson M, Shortened duration of human chorionic gonadotrophin surveillance following complete or partial hydatidiform mole: evidence for revised protocol of a UK regional trophoblastic disease unitBJOG 2007 114(6):760-62. [Google Scholar]

[15]. Batorfi J, Vegh G, Szepesi J, Szigetvari I, Doszpod J, Fulop V, How long should patients be followed after molar pregnancy? Analysis of serum hCG follow-up dataEur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2004 112(1):95-97. [Google Scholar]

[16]. Feltmate CM, Batorfi J, Fulop V, Goldstein DP, Doszpod J, Berkowitz RS, Human chorionic gonadotropin follow-up in patients with molar pregnancy: a time for reevaluationObstet Gynecol 2003 101(4):732-36. [Google Scholar]